Scottish Landform Examples the Cairngorms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Best of Walking in Scotland

1 The Best of Walking in Scotland Scotland is a land of contrasts—an ancient country with a modern outlook, where well-loved traditions mingle with the latest technology. Here you can tread on some of the oldest rocks in the world and wander among standing stones and chambered cairns erected 5,000 years ago. However, that little cottage you pass may have a high-speed Internet connection and be home to a jewelry designer or an architect of eco-friendly houses. Certainly, you’ll encounter all the shortbread and tartan you expect, though kilts are normally reserved for weddings and football matches. But far more traditional, although less obviously so, is the warm welcome you’ll receive from the locals. The farther you go from the big cities, the more time people have to talk—you’ll find they have a genuine interest in where you come from and what you do. Scotland’s greatest asset is its clean, green landscapes, where walkers can fill their lungs with pure, fresh air. It may only be a wee (small) country, but it has a variety of walks to rival anywhere in the world. As well as the splendid mountain hikes to be found in the Highlands, there’s an equal extent of Lowland terrain with gentle riverside walks and woodland strolls. The indented coastline and numerous islands mean that there are thousands of miles of shore to explore, while the many low hills offer exquisite views over the countryside. There’s walking to suit all ages and tastes. Some glorious countryside with rolling farmland, lush woods, and grassy hills can be reached within an hour’s drive of Edinburgh and Glasgow. -

Scottish Highlands Hillwalking

SHHG-3 back cover-Q8__- 15/12/16 9:08 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Scottish Highlands Hillwalking 60 DAY-WALKS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED TRAIL MAPS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED 60 DAY-WALKS 3 ScottishScottish HighlandsHighlands EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. They are particularly strong on mapping...’ HillwalkingHillwalking THE SUNDAY TIMES Scotland’s Highlands and Islands contain some of the GUIDEGUIDE finest mountain scenery in Europe and by far the best way to experience it is on foot 60 day-walks – includes 90 detailed trail maps o John PLANNING – PLACES TO STAY – PLACES TO EAT 60 day-walks – for all abilities. Graded Stornoway Durness O’Groats for difficulty, terrain and strenuousness. Selected from every corner of the region Kinlochewe JIMJIM MANTHORPEMANTHORPE and ranging from well-known peaks such Portree Inverness Grimsay as Ben Nevis and Cairn Gorm to lesser- Aberdeen Fort known hills such as Suilven and Clisham. William Braemar PitlochryPitlochry o 2-day and 3-day treks – some of the Glencoe Bridge Dundee walks have been linked to form multi-day 0 40km of Orchy 0 25 miles treks such as the Great Traverse. GlasgowGla sgow EDINBURGH o 90 walking maps with unique map- Ayr ping features – walking times, directions, tricky junctions, places to stay, places to 60 day-walks eat, points of interest. These are not gen- for all abilities. eral-purpose maps but fully edited maps Graded for difficulty, drawn by walkers for walkers. terrain and o Detailed public transport information strenuousness o 62 gateway towns and villages 90 walking maps Much more than just a walking guide, this book includes guides to 62 gateway towns 62 guides and villages: what to see, where to eat, to gateway towns where to stay; pubs, hotels, B&Bs, camp- sites, bunkhouses, bothies, hostels. -

Tartan Collection Carpet Specification

Tartan Product Profile Carpet Details: Specification General Information Construction: Woven Axminster Pile reversal: All cut pile carpets can suffer from pile Texture: Cut Pile Velour reversal and in certain instances this may become permanently bent or distorted for no specific reason Pitch: 7 per inch/27.6 per dcm that research has yet identified, giving areas of Rows: 8 per inch/31.4 per dcm light and shade. This is also known as “shading” or Pile Weight: *1260g/m2 - 1310g/m2 “watermarking”. It is not a defect in manufacture, it only occurs in a small percentage of all carpets Total Weight: *2070g/m2 - 2500g/m2 and no liabililty whatsoever can be accepted by the Tuft Density per m2: 86,940 manufacturer in respect of it. Pile pressure: All cut pile carpets are liable to show Backing: Woven Polyester/Polypropylene or Woven light and dark patches resulting from disturbance of Jute/Cotton the pile created by foot traffic or brushing, This is a Pile Yarn Content: 80% Wool, 20% Nylon normal feature and is not a defect in manufacture and no liability whatsoever can be accepted by the Pile Height: 7.5mm (Total height: 10.5mm) manufacturer in respect of it. Yarn count & tex 2 Ply/47’s, R660 tex or 2/42’s, R740 tex Pale shades: We include within our collection a number of pale shades. Primarily these are used Width: 4m as top or highlight colours. These more delicate * Design Dependent shades will invariably tend to soil more quickly and give a lower of light fastness than the norm, and may Tested for show natural blemishes within the fibre that tend to Suitability be masked in deeper shades containing a greater Extra Heavy Domestic/Heavy Contract quantity of dyestuff. -

Place-Names of the Cairngorms National Park

Place-Names of the Cairngorms National Park Place-Names in the Cairngorms This leaflet provides an introduction to the background, meanings and pronunciation of a selection of the place-names in the Cairngorms National Park including some of the settlements, hills, woodlands, rivers and lochs in the Angus Glens, Strathdon, Deeside, Glen Avon, Glen Livet, Badenoch and Strathspey. Place-names give us some insight into the culture, history, environment and wildlife of the Park. They were used to help identify natural and built landscape features and also to commemorate events and people. The names on today’s maps, as well as describing landscape features, remind us of some of the associated local folklore. For example, according to local tradition, the River Avon (Aan): Uisge Athfhinn – Water of the Very Bright One – is said to be named after Athfhinn, the wife of Fionn (the legendary Celtic warrior) who supposedly drowned while trying to cross this river. The name ‘Cairngorms’ was first coined by non-Gaelic speaking visitors around 200 years ago to refer collectively to the range of mountains that lie between Strathspey and Deeside. Some local people still call these mountains by their original Gaelic name – Am Monadh Ruadh or ‘The Russet- coloured Mountain Range’.These mountains form the heart of the Cairngorms National Park – Pàirc Nàiseanta a’ Mhonaidh Ruaidh. Invercauld Bridge over the River Dee Linguistic Heritage Some of the earliest place-names derive from the languages spoken by the Picts, who ruled large areas of Scotland north of the Forth at one time. The principal language spoken amongst the Picts seems to have been a ‘P-Celtic’ one (related to Welsh, Cornish, Breton and Gaulish). -

The Special Landscape Qualities of the Cairngorms National Park SNH Commissioned Report, No.375

From SNH & CNPA (2010). The special landscape qualities of the Cairngorms National Park SNH Commissioned Report, No.375 THE SPECIAL LANDSCAPE QUALITIES OF THE CAIRNGORMS NATIONAL PARK Note: The special qualities given here are for the National Park as a whole, including the proposed extension in 2010. The qualities of the two National Scenic Areas (NSAs) have not been listed separately. The Cairngorm Mountains NSA and the Deeside & Lochnagar NSA are centred on the highest mountain plateaux at the core of the park. They cover a significant proportion of the National Park and both include lower hills and areas of moorland, woodland and inhabited strath which characterise much of the park. It is for this reason that an analysis has shown that a list of the special qualities of these NSAs does not differ significantly from the list of qualities of the Park as a whole. Summary List of the Special Qualities 1.0 General Qualities • Magnificent mountains towering over moorland, forest and strath • Vastness of space, scale and height • Strong juxtaposition of contrasting landscapes • A landscape of layers, from inhabited strath to remote, uninhabited upland • ‘The harmony of complicated curves’ • Landscapes both cultural and natural 2.0 The Mountains and Plateaux • The unifying presence of the central mountains • An imposing massif of strong dramatic character • The unique plateaux of vast scale, distinctive landforms and exposed, boulder- strewn high ground • The surrounding hills • The drama of deep corries • Exceptional glacial landforms • -

'Hill of Fame' Munros

Glenrothes Hillwalkers Club 'Hill of Fame' Munros Scotlands 3000 feet and higher, main summits, originally listed by Hugh Munro. Now updated by The Scottish Mountaineering Club who maintain the list of 'compleatists'. There are currently 282 Munros and 226 subsidiary 'Tops' Glenrothes Hillwalkers Club 'Compleatists' Name Date of Completion Final Hill Note Bill Cluckie May-95 Liathach 1 Roger Holme May-99 Ben Hope John Urqhart Sep-99 Sgurr Mhic Choinnich Caroline Gordon Sept 02 Ben Klibreck Steve Thurgood ? Meall Chuaich 2 Wendy Jack Aug 05 Carn Dearg (Newtonmore) 3 Albert Duthie Jun-06 Sgurr Fiona, An Teallach 15 Wanda Elder Sep-06 Sgurr Mor (Loch Quoich) 4 Mick Allsop Jul-07 Seana Braigh 5 Bob Barlow Sept 07 Meall nan Tarmachan 6 Kate Thomson May-08 Beinn a' Chlaidheimh 7 Cameron Campbell Jul-09 Schiehallion 11 Wendy Georgeson Aug-09 Ben More (Mull) 9 Norman Georgeson Aug-09 Ben More (Mull) 9 Janice Duncan Sep-10 Ben Avon 13 Dave Lawson Jul-11 Ben More (Mull) 14 George WalkingshawJul-11 Ben More (Mull) 10 Colin Cushnie Jul-13 Bidean a Ghlas Thuill, An Teallach Neil Redpath May-15 Braeriach Sandra Smith May-16 Carn Mor Dearg Jim Davies Aug-16 The Saddle Ian Morris Oct-16 Sgorr Dhonuill Members who have climbed more than 200 Janice Thomson 8 Eileen Macdonald Ian Ireland Syd Hadfield Charlie Hughes Julie Garland Jim Fleming Harry Dryburgh Andrew Frame 12 Sylvia Stronach Jim Anderson Brian Robertson 1st Munro with the club Andrew Frame May-02 Blaven 12 Andy Brown Jun-07 Dreish George Walkingshaw Apr-99 Ben Macdui 10 Linda Cox ? 06 Ben Dorain Brian Robertson Mar-13 Ben Challum Bob Crosbie Apr-15 Carn na Caim Ed Watson Apr-15 Carn na Caim Jackie Beatson Jun-15 Sgorr Dhonuill Jenny White Jun-15 Sgorr Dhonuill Scott Finnie Jun-15 Sgorr Dhearg Kirsten Holt Jun-15 Sgorr Dhearg Anna Paterson Jun-15 Sgorr Dhearg Munro Tops Bob Barlow Sep-13 Creag na Caillich (Meall nan Tarmachan)6 6 Corbetts Scotlands 2500 to 3000 Feet summits with a clear drop of 500 Feet all round. -

Scotland's Landscape: Physical Features

Scotland's Landscape: Physical Features I can describe the major characteristic features of Scotland’s landscape and explain how these were formed. SOC 2-07a What are the physical features of a landscape? Can you list some of the physical features of Scotland’s landscape? Circle the words in the table below that are physical features of Scotland’s landscape: bridges mountains football stadiums rivers glens hills motorways islands coastline lochs Choose one of the physical features of Scotland’s landscape; what facts can you find out about it? Write your facts in the space below. Something extra… Think about how you could present these facts to the rest of the class! twinkl.co.uk Page 1 of 7 Scotland's Landscape: Physical Features I can describe the major characteristic features of Scotland’s landscape and explain how these were formed. SOC 2-07a On this map of Scotland, identify, colour and label these areas: the Highlands and Islands, the Central Lowlands and the Southern Uplands. Complete the key for your map. Legend Highlands and Islands Central Lowlands Southern Uplands twinkl.co.uk Page 2 of 7 Scotland's Landscape: Physical Features I can describe the major characteristic features of Scotland’s landscape and explain how these were formed. SOC 2-07a On this map of Scotland, identify and mark these mountain ranges: Grampians, Cairngorms, and the Cuillin mountains. Top Ten Highest Mountains in Height in Top Ten Highest Mountains in Height in Scotland Metres Scotland Metres 1. Ben Nevis 6. Cairn Gorm 2. Ben Macdui 7. Aonach Beag 3. -

Calendar of Events 2021

Calendar of Events 2021 April 30 Apr Aonach Eagach Guided day rock-scrambling along the Aonach Eagach Ridge in Central Highlands, 2 Munros Summits : Meall Dearg (Aonach Eagach), Sgorr nam Fiannaidh (Aonach Eagach) http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-aonach-eagach.html May 1-2 May Kintail's Brothers and Sisters Hillwalking days on high crests in the Western Highlands, 7 Munros Summits : Ciste Dhubh, Aonach Meadhoin, Sgurr a' Bhealaich Dheirg, Saileag, Sgurr na Ciste Duibhe, Sgurr na Carnach, Sgurr Fhuaran http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-kintail.html 3-4 May Kintail Bookends Hill-walking day in the Western Highlands, 5 Munros Summits : Carn Ghluasaid, Sgurr nan Conbhairean, Sail Chaorainn, A' Ghlas-bheinn, Beinn Fhada http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-cluanie.html 4-7 May Skye Munros Hill-walking and rock-scrambling to summit the 11 Munros on the Cuillin Ridge of Skye. Includes some moderate climbing on the Inaccessible Pinnacle and Sgurr nan Gillean Summits : Sgurr nan Eag, Sgurr Dubh Mor, Sgurr Alasdair, Sgurr Mhic Choinnich, Sgurr Dearg - the Inaccessible Pinnacle, Sgurr na Banachdich, Sgurr a' Ghreadaidh, Sgurr a' Mhadaidh, Sgurr nan Gillean, Am Basteir, Bruach na Frithe http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-skye-munros.html 7 May An Teallach Day rock-scrambling the An Teallach main ridge in the Northern Highlands, 2 Munros Summits : An Teallach - Sgurr Fiona, An Teallach - Bidein a' Ghlas Thuill http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-anteallach.html 8-10 May Inverlael Munros Extended hill-walking weekend in the Northern Highlands, 6 Munro Summits : Eididh nan Clach Geala, Meall nan Ceapraichean, Cona' Mheall, Beinn Dearg, Seana Bhraigh, Am Faochagach http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-inverlael.html 10 May Aonach Eagach Guided day rock-scrambling along the Aonach Eagach Ridge in Central Highlands, 2 Munros Summits : Meall Dearg (Aonach Eagach), Sgorr nam Fiannaidh (Aonach Eagach) http://www.stevenfallon.co.uk/guide-aonach-eagach.html 11-14 May Skye Munros Hill-walking and rock-scrambling to summit the 11 Munros on the Cuillin Ridge of Skye. -

Natural Heritage Zones: a National Assessment of Scotland's

NATURAL HERITAGE ZONES: A NATIONAL ASSESSMENT OF SCOTLAND’S LANDSCAPES Contents Purpose of document 6 An introduction to landscape 7 The role of SNH 7 Landscape assessment 8 PART 1 OVERVIEW OF SCOTLAND'S LANDSCAPE 9 1 Scotland’s landscape: a descriptive overview 10 Highlands 10 Northern and western coastline 13 Eastern coastline 13 Central lowlands 13 Lowlands 13 2 Nationally significant landscape characteristics 18 Openness 18 Intervisibility 18 Naturalness 19 Natural processes 19 Remoteness 19 Infrastructure 20 3 Forces for change in the landscape 21 Changes in landuse (1950–2000) 21 Current landuse trends 25 Changes in development pattern 1950–2001 25 Changes in perception (1950–2001) 32 Managing landscape change 34 4 Landscape character: threats and opportunities 36 References 40 PART 2 LANDSCAPE PROFILES: A WORKING GUIDE 42 ZONE 1 SHETLAND 43 1 Nature of the landscape resource 43 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 51 3 Landscape and trends in the zone 51 4 Building a sustainable future 53 ZONE 2 NORTH CAITHNESS AND ORKNEY 54 Page 2 11 January, 2002 1 Nature of the landscape resource 54 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 72 3 Landscape and trends in the zone 72 4 Building a sustainable future 75 ZONE 3 WESTERN ISLES 76 1 Nature of the landscape resource 76 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 88 3 Landscape and trends in the zone 89 4 Building a sustainable future 92 ZONE 4 NORTH WEST SEABOARD 93 1 Nature of the landscape resource 93 2 Importance and value of the zone landscape 107 3 Landscape and trends -

Scotland's Munros – Answers

Scotland’s Munros Answers 1. What does to bag a Munro mean? To bag a Munro means to climb a mountain that is over 3000 feet or 914.4m high. 2. When were Munros first listed? Munros were first listed in 1891. 3. Who first listed all the Munros? The Munros were first listed by Sir High Munro. 4. How many Munros did Sir Hugh say there were? Sir Hugh said there were 283 Munros. 5. Who keeps the list of Munros up to date? The list of Munros is kept up to date by the Scottish Mountaineering Club. 6. How many Munros are there thought to be today? There are thought to be 282 Munros. 7. What is the name given to someone who climbs all the Munros? Someone who climbs all the Munros is a Compleatists or Munroist. 8. Why should someone who goes Munro-bagging plan their climb carefully? Someone who goes Munro-bagging should plan their climb carefully because Scotland’s mountains are extremely dangerous in bad weather or if you are not properly equipped. Page 1 of 1 Scotland’s Munros Answers 1. Who takes part in Munro-bagging in Scotland? Munro-bagging is a popular pastime for hill walkers, climbers and mountaineers. 2. What does to bag a Munro mean? To bag a Munro means to climb to the top of a mountain that is over 3000 feet or 914.4m high. 3. Why are these mountains called Munros? They are called Munros because they were first identified in 1891 by Sir Hugh Munro. -

Geology of the Newtonmore-Ben Macdui District: Bedrock And

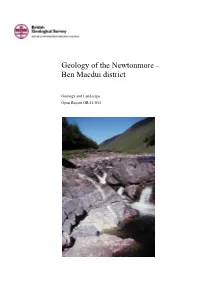

Geology of the Newtonmore – Ben Macdui district Geology and Landscape Open Report OR/11/055 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Geology and Landscape OPEN REPORT OR/11/055 The National Grid and other Bedrock and Superficial Geology of the Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Newtonmore – Ben Macdui district: Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2011. Description for Sheet 64 (Scotland) Keywords R A Smith, J W Merritt, A G Leslie, M Krabbendam and D Newtonmore, Ben Macdui, Stephenson geology. Front cover Contributors James Hutton’s Locality above B C Chacksfield, N R Golledge, E R Phillips Dail-an-Eas Bridge [NN 9388 7467], looking north-east up Glen Tilt whose trend is largely controlled by the Loch Tay Fault. Here Hutton observed granite veins cutting and recrystallising Dalradian metasedimentary rocks and deduced that granite crystallised from a hot liquid. BGS Imagebase P601616. Bibliographical reference SMITH, R A, MERRITT, J W, LESLIE, A G, KRABBENDAM, M, AND STEPHENSON, D. 2011. Bedrock and Superficial Geology of the Newtonmore – Ben Macdui district: Description for Sheet 64 (Scotland). British Geological Survey Internal Report, OR/11/055. 122pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. -

Summits on the Air Scotland

Summits on the Air Scotland (GM) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S4.1 Issue number 1.3 Date of issue 01-Sep-2009 Participation start date 01-July-2002 Authorised Tom Read M1EYP Date 01-Sep-2009 Association Manager Andy Sinclair MM0FMF Management Team G0HJQ, G3WGV, G3VQO, G0AZS, G8ADD, GM4ZFZ, M1EYP, GM4TOE Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. The source data used in the Marilyn lists herein is copyright of Alan Dawson and is used with his permission. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Summits on the Air – ARM for Scotland (GM) Page 2 of 47 Document S4.1 Summits on the Air – ARM for Scotland (GM) Table of contents 1 CHANGE CONTROL ................................................................................................................................. 4 2 ASSOCIATION REFERENCE DATA ...................................................................................................... 5 2.1 PROGRAMME DERIVATION ..................................................................................................................... 5 2.1.1 Mapping to Marilyn regions ............................................................................................................. 6 2.2 MANAGEMENT OF SOTA SCOTLAND ..................................................................................................... 7 2.3 GENERAL INFORMATION .......................................................................................................................