Ten Basic Responsibilities of Nonprofit Boards

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Boards Drive Value in Family-Owned Businesses

A Enduring Across Generations—How Boards Drive Value in Family-Owned Businesses ENDURING ACROSS GENERATIONS How Boards Drive Value in Family-Owned Businesses © 2015 | WomenCorporateDirectors. All materials, logos, etc., unless otherwise stated, are the property of WomenCorporateDirectors, Ltd. Copyright and other intellectual property laws protect these materials. Reproduction or retransmission of the materials, in whole or in part, in any manner, without the prior written consent of the copyright holder, is a violation of copyright law. Contact information for requests for permission to reproduce or distribute materials: [email protected]. © 2015 KPMG LLP, a Delaware limited liability partnership and the U.S. member firm of the KPMG network of independent member firms affiliated with KPMG International Cooperative (“KPMG International”), a Swiss entity. All rights reserved. The KPMG name, logo and “cutting through complexity” are registered trademarks or trademarks of KPMG International. NDPPS 310255 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapter 1 – The Benefits of Governance 2 Chapter 2 – The Three Enablers: Clarity, Culture, Communication 3 Chapter 3 – Building a Strong Board 8 Chapter 4 – Keys to an Effective Family Business Board 13 Chapter 5 – Cultivating and Motivating Talent 19 Conclusion 23 WCD Thought Leadership Council 25 2015 WCD Thought Leadership Commissioners 26 Unless otherwise designated, all persons quoted in this report are WCD Thought Leadership Council Members or Commissioners. A full list of Council Members and Commissioners appears on pages 25 – 28. © 2015 | WomenCorporateDirectors. All materials, logos, etc., unless otherwise stated, are the property of WomenCorporateDirectors, Ltd. Copyright and other intellectual property laws protect these materials. Reproduction or retransmission of the materials, in whole or in part, in any manner, without the prior written consent of the copyright holder, is a violation of copyright law. -

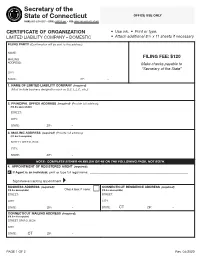

Certificate of Organization (LLC

Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] • WEB: www.concord-sots.ct.gov CERTIFICATE OF ORGANIZATION • Use ink. • Print or type. LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY – DOMESTIC • Attach additional 8 ½ x 11 sheets if necessary. FILING PARTY (Confirmation will be sent to this address): NAME: FILING FEE: $120 MAILING ADDRESS: Make checks payable to “Secretary of the State” CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 1. NAME OF LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY (required) (Must include business designation such as LLC, L.L.C., etc.): 2. PRINCIPAL OFFICE ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – 3. MAILING ADDRESS (required) (Provide full address): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – NOTE: COMPLETE EITHER 4A BELOW OR 4B ON THE FOLLOWING PAGE, NOT BOTH. 4. APPOINTMENT OF REGISTERED AGENT (required): A. If Agent is an individual, print or type full legal name: _______________________________________________________________ Signature accepting appointment ▸ ____________________________________________________________________________________ BUSINESS ADDRESS (required): CONNECTICUT RESIDENCE ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box unacceptable) Check box if none: (P.O. Box unacceptable) STREET: STREET: CITY: CITY: STATE: ZIP: – STATE: CT ZIP: – CONNECTICUT MAILING ADDRESS (required): (P.O. Box IS acceptable) STREET OR P.O. BOX: CITY: STATE: CT ZIP: – PAGE 1 OF 2 Rev. 04/2020 Secretary of the State of Connecticut OFFICE USE ONLY PHONE: 860-509-6003 • EMAIL: [email protected] -

Basic Responsibilities of the Co-Op Board of Directors

OVERVIEW BASIC RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE CO-OP BOARD OF DIRECTORS At start-up co-ops develop documents that spell out how the organization will operate. The corporate code often sets legal parameters for the co-op. The Articles of Incorporation contain the purpose of the co-op and its legal definitions. This document is filed with the Secretary of State. The Bylaws include the over-arching rules of the co- ops such as when where and how decisions will be made. The Board of Directors is the legal entity responsible for directing the affairs of the corporation. Every corporation MUST have a board. If a co-op operates as a collective then technically all members are on the Board. The Board must follow the rules set out in the Corporate Code, the Articles of Incorporation, and the Bylaws. Bylaw changes usually require a full membership vote to change. The members of the cooperative elect the Board.1 Three legal charges for Boards are fiduciary duty, duty of loyalty and duty of care. As trustees of the cooperative, board members have a special relationship to the cooperative to make business decisions focused only on what benefits the cooperative and all of its members. Decisions must be based on careful consideration of the issues. The fundamental legal standard for board members is to act in good faith, in a manner they believe to be in the best interests of the cooperative, and with such care, including reasonable inquiry, as an ordinary prudent person in a like position would use under similar circumstances. -

The Circle of Responsibilities for Co-Op Boards

The Circle of Responsibilities for Co-op Boards REPRINT Management Tip Series By James Baarda Foreword All boards of directors are under increasing pressure to perform well and justify their decisions. Cooperative boards are no exception. But increasing scrutiny of director behavior is not always accompanied by better information about exactly what directors are supposed to do and how they are to perform their many duties. The series of articles reprinted here originally appeared during 2002 as Management Tip articles in three issues of USDA’s "Rural Cooperatives" magazine. These articles lay out fundamental guidelines for cooperative directors. Along with practical guides, the articles explain underlying principles and give suggestions for specific actions cooperative boards and directors can take to improve their service to cooperatives. Cooperative members can use this well-received series to assess board and individual director performance and make informed choices about directors. Directors can apply the information to carry out the full range of their responsibilities with the assurance that they are satisfying the high standards of conduct required of them. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sexual orientation, and marital or family status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, Room 326-W, Whitten Building, 14th and Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. -

Corporate Governance of Company Groups: International and Latin American Experience

Corporate Governance of Company Groups: International and Latin American Experience Preliminary version for comment. Hosted by : Please send written comments to [email protected] by 5 December, 2014 Latin American Roundtable Task Force on Corporate Governance of Company Groups 17 November, 2014 Hotel Hilton Bogotá, CARRERA 7 NO. 72-41, BOGOTA, 00000, COLOMBIA http://www.oecd.org/daf/ca/latinamericanroundtableoncorporategovernance.htm With funding support of: TABLE OF CONTENTS International and Latin American Overview ............................................................................. 3 1. Introduction............................................................................................................................ 3 2. Economic Rationale for Corporate Groups and the Role of Corporate Governance ............. 4 3. International Work on Corporate Governance of Groups ...................................................... 8 4. Economic Relevance of Company Groups in LatAm .......................................................... 12 5. What is an Economic Group in LatAm? .............................................................................. 12 6. Structure of the Regulatory and Supervisory Framework ................................................... 13 7. Protection of Minority Shareholder Rights .......................................................................... 14 8. Economic Groups and Conflicts of Interest ......................................................................... 15 9. Multinational -

Organizational Culture Model

A MODEL of ORGANIZATIONAL CULTURE By Don Arendt – Dec. 2008 In discussions on the subjects of system safety and safety management, we hear a lot about “safety culture,” but less is said about how these concepts relate to things we can observe, test, and manage. The model in the diagram below can be used to illustrate components of the system, psychological elements of the people in the system and their individual and collective behaviors in terms of system performance. This model is based on work started by Stanford psychologist Albert Bandura in the 1970’s. It’s also featured in E. Scott Geller’s text, The Psychology of Safety Handbook. Bandura called the interaction between these elements “reciprocal determinism.” We don’t need to know that but it basically means that the elements in the system can cause each other. One element can affect the others or be affected by the others. System and Environment The first element we should consider is the system/environment element. This is where the processes of the SMS “live.” This is also the most tangible of the elements and the one that can be most directly affected by management actions. The organization’s policy, organizational structure, accountability frameworks, procedures, controls, facilities, equipment, and software that make up the workplace conditions under which employees work all reside in this element. Elements of the operational environment such as markets, industry standards, legal and regulatory frameworks, and business relations such as contracts and alliances also affect the make up part of the system’s environment. These elements together form the vital underpinnings of this thing we call “culture.” Psychology The next element, the psychological element, concerns how the people in the organization think and feel about various aspects of organizational performance, including safety. -

Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Electronic Theses and Dissertations Spring 5-2019 Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship Jacob Martin [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Martin, Jacob, "Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship" (2019). Digital Commons @ ACU, Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 124. This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. This dissertation, directed and approved by the candidate’s committee, has been accepted by the College of Graduate and Professional Studies of Abilene Christian University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership Dr. Joey Cope, Dean of the College of Graduate and Professional Studies Date Dissertation Committee: Dr. First Name Last Name, Chair Dr. First Name Last Name Dr. First Name Last Name Abilene Christian University School of Educational Leadership Customer Relationship Management and Leadership Sponsorship A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership by Jacob Martin December 2018 i Acknowledgments I would not have been able to complete this journey without the support of my family. My wife, Christal, has especially been supportive, and I greatly appreciate her patience with the many hours this has taken over the last few years. I also owe gratitude for the extra push and timely encouragement from my parents, Joe Don and Janet, and my granddad Dee. -

Hands on Board: the Board of Volunteers in an All-Volunteer

All Hands on Board The Board of Directors in an All-Volunteer Organization By Jan Masaoka BOARDSOURCE E-BOOK SERIES BOARDSOURCE E-BOOK SERIES Volunteerism is an enormous economic force, yet it is never mentioned in business school or in economics departments. — Charles Hoadley, former Chief Economist, Bank of America WHAT IS AN “ALL-VOLUNTEER ORGANIZATION”? If you are reading this handbook, you are part of a huge economic force — that of the all-volunteer organization (AVO). Among other tasks, members of AVOs clean up beaches, care for the dying, coach basketball teams, advocate for gun control, rescue abused animals, raise their voices in song, publish literary journals, raise scholarship funds, preserve local history, serve as volunteer fire departments, exchange heirloom seeds, host visitors from foreign countries, help people conquer alcoholism, change public perception about the disabled, and help adoptees and birth parents find each other. They make our communities, however defined, work better. That these and countless other services are provided by volunteers and not by paid staff of a nonprofit, business, or government agency would come as a surprise to many. In fact, those of us in all-volunteer organizations often don’t even think of ourselves as the important economic and social force that we are. A WORD ON TERMINOLOGY When we use the term “all-volunteer organization (AVO),” we mean a nonprofit organi- zation in which volunteers manage the organization and do most or all of the work. Some soccer leagues pay referees for Saturday games, some historic preservation societies pay gardeners, and some PTAs pay after-school art teachers. -

English Business Organization Law During the Industrial Revolution

Choosing the Partnership: English Business Organization Law During the Industrial Revolution Ryan Bubb* I. INTRODUCTION For most of the period associated with the Industrial Revolution in Britain, English law restricted access to incorporation and the Bubble Act explicitly outlawed the formation of unincorporated joint stock com- panies with transferable shares. Furthermore, firms in the manufacturing industries most closely associated with the Industrial Revolution were overwhelmingly partnerships. These two facts have led some scholars to posit that the antiquated business organization law was a constraint on the structural transformation and growth that characterized the British economy during the period. For example, Professor Ron Harris argues that the limitation on the joint stock form was “less than satisfactory in terms of overall social costs, efficient allocation of resources, and even- 1 tually the rate of growth of the English economy.” * Associate Professor of Law, New York University School of Law. Email: [email protected]. For helpful comments I am grateful to Ed Glaeser, Ron Harris, Eric Hilt, Giacomo Ponzetto, Max Schanzenbach, and participants in the Berle VI Symposium at Seattle University Law School, the NYU Legal History Colloquium, and the Harvard Economic History Tea. I thank Alex Seretakis for superb research assistance. 1. RON HARRIS, INDUSTRIALIZING ENGLISH LAW: ENTREPRENEURSHIP AND BUSINESS ORGANIZATION, 1720–1844, at 167 (2000). There are numerous other examples of this and related arguments in the literature. While acknowledging that, to a large extent, restrictions on the joint stock form could be overcome by alternative arrangements, Nick Crafts nonetheless argues that “institutional weaknesses relating to . company legislation . must have had some inhibiting effects both on savers and on business investment.” Nick Crafts, The Industrial Revolution, in 1 THE ECONOMIC HISTORY OF BRITAIN SINCE 1700, at 44, 52 (Roderick Floud & Donald N. -

The Constitution of Seidman Supply Chain Management Association of Grand Valley State University Preamble

The Constitution of Seidman Supply Chain Management Association of Grand Valley State University Preamble: We, the Seidman Supply Chain Management Association of Grand Valley State University are dedicated to educating students about the profession of Supply Chain Management. Article One: Name The name of this organization established by this constitution shall be Seidman Supply Chain Management Association of Grand Valley State University, and may be hereinafter referred to as SSCMA of GVSU. Article Two: Purpose The purpose of this organization shall be to combine the American Production and Inventory Control Society of Grand Valley State University and the Council of Supply Chain Management Professionals of Grand Valley State University into one organization called SSCMA. The purpose of this organization is to provide opportunities for students interested in supply chain management to communicate and learn from supply chain management professionals in order to improve their supply chain management knowledge. The organization will provide networking, learning, and career opportunities. Through professional events, such as guest speakers, lectures about current events, and member recruiting events, SSCMA of GVSU will also create awareness of the significance of supply chain management. Article Three: Membership Section One: General Assembly Membership 3.1.1 The membership of SSCMA of GVSU is determined based on the criteria outlined in the APICS of GVSU constitution, and the CSCMP of GSVU constitution. Section Two: Dues and Fees 3.2.1 There is no membership fee for SSCMA of GVSU members. Article Four: Executive Board Section One: Description 4.1.1 The Executive Board shall consist of six (6) core members: A. -

A Guide to Nonprofit Board Service in Oregon

A GUIDE TO NONPROFIT BOARD SERVICE IN OREGON Office of the Attorney General A GUIDE TO NONPROFIT BOARD SERVICE Dear Board Member: Thank you for serving as a director of a nonprofit charitable corporation. Oregonians rely heavily on charitable corporations to provide many public benefits, and our quality of life is dependent upon the many volunteer directors who are willing to give of their time and talents. Although charitable corporations vary a great deal in size, structure and mission, there are a number of principles which apply to all such organizations. This guide is provided by the Attorney General’s office to assist board members in performing these important functions. It is only a guide and is not meant to suggest the exact manner that board members must act in all situations. Specific legal questions should be directed to your attorney. Nevertheless, we believe that this guide will help you understand the three “R”s associated with your board participation: your role, your rights, and your responsibilities. Active participation in charitable causes is critical to improving the quality of life for all Oregonians. On behalf of the public, I appreciate your dedicated service. Sincerely, Ellen F. Rosenblum Attorney General 1 UNDERSTANDING YOUR ROLE Board members are recruited for a variety of reasons. Some individuals are talented fundraisers and are sought by charities for that reason. Others bring credibility and prestige to an organization. But whatever the other reasons for service, the principal role of the board member is stewardship. The directors of the corporation are ultimately responsible for the management of the affairs of the charity. -

Board of Directors' Partnership Agreement

Board of Directors’ Partnership Agreement Boards work as a team and each member of the team contributes to helping make the organization effective. Each board member is expected to be an active participant in the Fresno State Alumni Association (FSAA) to ensure that it fulfills its mission in support of the Fresno State. This agreement outlines the expectations of all FSAA Board members. Alumni Association Director Responsibilities: • Be an Ambassador for the Association and promote our primary principles of engagement, recognition and scholarships • Be informed of the FSAA’s mission, services, policies and programs • Be a donor of the FSAA at the Life level or greater (lifetime commitment of $1,000+) • Make an annual gift to the FSAA (any amount, made between July 1 st and June 30 th ) • Purchase or sell an entire table at the annual FSAA Top Dog Alumni Awards Gala recognition event (annual commitment of $1,250) • Utilize the FSAA’s online resources - Board Effect, FresnoStateAlumni.com and social media sites • Serve on one or more FSAA committees • Contribute to the development and successful implementation of the FSAA strategic plan • Collaborate with other board members in the best interest of the FSAA and Fresno State • Attend board and assigned FSAA committee meetings • Attend and support the following FSAA special events: • Top Dog Alumni Awards Gala • Recognition events • Student engagement events and activities • Annual Board of Directors Dinner • Other Board events designated by the Executive Committee Association staff will: • Provide timely information and support to assist the Directors in accomplishing their tasks. • Provide linkages to campus units.