Does Quality Council Status Produce Quality Councils?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messenger May 2021 50P

Q U A N T O C K C O T N A U Q for Nether Stowey & Over Stowey & Over Stowey for Nether Messenger May 2021 50p 1 Belinda’s Soft Toys Sadly, Belinda Penn died at the beginning of March. Many of you will know Belinda had spent the past few years knitting favourite characters to raise funds for Dementia Care. PLEASE HELP to continue to raise funds in buying the toys which are on sale in the Library and Post Office at a very reasonable price of £5 and £8. I have many more toys which can be viewed at my home. I thank you in anticipation of your support for this worthy cause and in memory of Belinda Penn. Contact: Tina 07761586866 Physical books of condolence in public places for HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh are not permitted under current Covid-19 rules. If you would like to express your condolences, this can be done online through the Parish Council website or written comments can be handed in at the Parish Council office and they will be entered in a local Book of Condolence. “Former Ageing Well Manager, Di Ramsay, with 88 year old yoga teacher Ivy Thorne. Di tragically lost her battle with cancer last year. She was an inspirational leader, who made a huge difference to the wellbeing of many older people in Somerset”. 2 CLUBS & SOCIETIES IN NETHER STOWEY & OVER STOWEY Allotment Association Over Stowey Rights of Way Group Bruce Roper 732 043 Richard Ince 733 237 Active Living Group Over Stowey Social Club Call 734 613 or 733 040; 733 151; 732 609 Sue Thomas 732 905 Coleridge Probus Club Over Stowey Tennis Court Philip Comer (01984) -

Information Requests PP B3E 2 County Hall Taunton Somerset TA1

Information Requests PP B3E 2 Please ask for: David Boorer County Hall FOI Reference: 1526265 Taunton Direct Dial: 01823 359359 Somerset Email: [email protected] TA1 4DY Date: 30 August 2016 Mr Mike Newman Dear Mr Newman Freedom of Information Act 2000 I can confirm that the information you have requested is held by Somerset County Council. Your Request: Can you supply the amounts and recipients of grants from the Members Health & Wellbeing Scheme in the following wards: 1. Brent 2. Burnham-on-Sea North 3. Burnham-on-Sea South and Highbridge 4. Huntspill For: a. The 2015/16 financial year b. The 2016/17 financial year to date Our Response: I have detailed below the information that Somerset County Council hold. This information is for the financial year 2015/16. The Health and Wellbeing Scheme is not running for this financial year, 2016/17. Beneficiary Purpose Amount Brent N/A N/A Burnham-On-Sea, Sensational Kids £2,000.00 North Sensory Room Music for the Memory £2,000.00 Sedgemoor Play Day £1,000.00 Burnham-On-Sea, Red Bowls Club. £100.00 South & Highbridge Replace player boards Autism Somerset CiC. £3,500.00 Cover the cost of training, childcare cost, lunch, travel, room hire. Huntspill Puriton Parish Council. £750.00 Re-erect the old phone box Puriton Parish Council. £500.00 Over 60's club, including meals. Cossington Parish £800.00 Council. Purchase and install a bench in play area. Woolavington Parish £750.00 Council. Security cameras for village hall. East Huntspill Parish £1,000.00 Council. -

New Colleges L/Let.Indd

Town/Village Service number Town/Village Service number Aller 16 Norton Fitzwarren 613 Ashcott 75 Othery 16 Guide to buses serving Axbridge 66 Pawlett 21,62 Banwell 62 Puriton 66,75,X75 Berrow 21 Rockwell Green 623 Bishops Lydeard 613 Rooksbridge 21, 62 Bridgwater & Blackford 66 Shurton 14 Burnham-on-Sea 21 Sidcot 62 Burton 14 Spaxton 613 Taunton College Cannington 14,15,16,623,625 Stawell 19 Catcott 75 Stockland Bristol 14 Bridgwater Campus Chard 624 Stogursey 14 Cheddar 66 Street 75,X75 Academic Year 2019-20 Chedzoy 19 Sutton Mallet 19 Cocklake 66 Taunton 625 Combwich 14 Washford 15 Cossington 75 Watchet 15 Cotford St Luke 613 Wedmore 66 Dunball 21,75 Wellington 623 Durleigh 613 Wells X75 East Brent 21 Wembdon 14, 15 East Huntspill 66 West Huntspill 21 Enmore 613 Weston-Super-Mare 62 Glastonbury X75 West Quantoxhead 15 Goathurst 613 Westonzoyland 16 Greinton 19 Williton 15 Hawkridge Reservoir 613 Woolavington 66,75,X75 Highbridge 21,62 Holford 15 Bakers Dolphin Huish Episcopi 16 Weston - Highbridge - Bridgwater 62 Ilminster 624 Axbridge - Cheddar - East Huntspill - Bridgwater 66 Kilve 15 Buses of Somerset Kingston St Mary 613 Shurton - Bridgwater 14 Langport 16 Minehead - Bridgwater 15 Locking 62 Greinton - Moorlynch - Chedzoy - Bridgwater 19 Mark 66 Rooksbridge - Bridgwater 21 Middlezoy 16 Wells - Street - Glastonbury - Bridgwater 75/X75 Minehead 15 Rockwell Green - Wellington - Bridgwater College - Monkton Heathfield 623,625 Cannington College 623 Moorlinch 19 Taunton - Bridgwater College - Cannington College Nether Stowey 15 625 North -

Puriton Energy Park SPD March 2012

Puriton Energy Park Supplementary Planning Document (Adopted 28th March 2012) Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Status of Document 1.2 Purpose of the SPD Chapter 2 Strategic and Local Context 2.1 Strategic Context 2.2 Local Context Chapter 3 The Site 3.1 Historic Use 3.2 Scale and Character 3.3 Site Access 3.4 Current Position 3.5 Landscape Context Chapter 4 Planning Policy Context 4.1 Policy Context 4.2 Regional Spatial Strategy for the South West 4.3 Somerset and Exmoor national Park Joint Structure Plan Review (1991-2011) 4.4 Somerset Economic Assessment (March 2011) 4.5 Sedgemoor Economic Masterplan (2008-26) 4.6 Bridgwater Vision 4.7 Sedgemoor Core Strategy (2006-27) Policy S1: Spatial Strategy Policy MIP1: Major Infrastructure Proposals Policy D11: Economic Prosperity Policy P1: Bridgwater Urban Area Policy D2: Promoting High Quality and Inclusive Design Policy D4: Renewable or Low Carbon Energy Generation Other Relevant Policies (S2, S3, S4, MIP 1, D1, D3, D9, D10, D14, D16, D17, D19, D20, D21) 4.8 Sustainable Community Strategy for Sedgemoor (2009) 4.9 Sedgemoor Corporate Strategy (2009-14) 4.10 Sedgemoor Climate Change Strategy (draft 2012) 4.11 Sedgemoor Green Infrastructure Strategy (2011) 4.12 Sedgemoor Landscape Assessment (2003) 4.13 Somerset Waste Core Strategy (draft 2012) Chapter 5 Site Analysis 5.1 Principle of Redevelopment 5.2 Site Benefits and Constraints 5.3 Brownfield and Greenfield 5.4 Flood Risk 5.5 Biodiversity and Ecology 5.6 Transport and Accessibility Chapter 6 The Energy Park Concept 6.1 Defining the Energy -

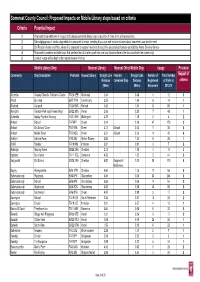

Consultation List of Mobile Stops and Potential Impact.Xlsx

Somerset County Council: Proposed Impacts on Mobile Library stops based on criteria Criteria Potential Impact 1 Proposed to be withdrawn in August 2015 because mobile library stop is less than 3 miles from a library building 2 School/playgroup or similar stop which it is proposed to retain, pending discussion with each institution about how needs can best be met 3 Old People's home or similar, where it is proposed to support residents through the personalised service provided by Home Delivery Service 4 Proposed to combine multiple stops that are less than 0.5 miles apart into one stop (location/time to be discussed with the community) 5 Level of usage will be kept under regular review in future Mobile Library Stop Nearest Library Nearest Other Mobile Stop Usage Potential Community Stop Description Postcode Nearest Library Straight Line Possible Straight Line Number of Total Number impact of Distance Combined Stop Distance Registered of Visits in criteria (Miles) (Miles) Borrowers 2013/14 Alcombe Cheeky Cherubs Children’s Centre TA24 5EB Minehead 0.64 0.38 1 12 2 Alford Bus stop BA7 7PWCastle Cary 2.05 1.44 6 19 1 Allerford Car park TA24 8HSPorlock 1.36 1.01 8 80 1 Alvington Fairacre Park (opp Fennel Way) BA22 8SA Yeovil 2.06 0.20 7 48 1 Ashbrittle Appley Pavillion Nursery TA21 0HH Wellington 4.22 1.18 2 4 2 Ashcott School TA79PP Street 3.04 0.18 47 179 2 Ashcott Old School Close TA7 9RA Street 3.12 Ashcott 0.13 11 35 4 Ashcott Middle Street TA7 9QG Street 3.01 Ashcott 0.13 14 45 4 Ashford Ashford Farm TA5 2NL Nether Stowey 2.86 1.10 6 -

Converted from C:\PCSPDF\PCS52117.TXT

M127-7 SEDGEMOOR DISTRICT COUNCIL CANDIDATES SUMMARY PARISH COUNCIL ELECTION - 3RD MAY 2007 Area Candidates Party Address Parish of Ashcott Adrian Scot Davis 20 School Hill, Ashcott, Somerset, DAVIS TA7 9PN Number of Seats : 8 Cilla Ann Thurlow Grain Ashcott Resident 3 Pedwell Lane, Ashcott, Bridgwater, GRAIN Somerset, TA7 9PD Joe Jenkins Saddle Stones, 31 Pedwell Hill, JENKINS Ashcott, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA7 9BD Jenny Lawrence 3 The Batch, Ashcott, Bridgwater, LAWRENCE Somerset, TA7 9PG Jack Miles Sayer 29 High Street, Ashcott, Bridgwater, SAYER TA7 9PZ Axbridge Town Council Dennis Bratt Past Mayor of Axbridge 62 Knightstone Close, Axbridge, BRATT Somerset, BS26 2DJ Number of Seats : 13 Kate Walker Independent 36 Houlgate Way, Axbridge, Somerset, Browne BS26 2BY BROWNE Christopher Byrne Wavering Down, Webbington Road, BYRNE Cross, Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2EL Jeremy Gall 6 Moorland St, Axbridge, BS26 2BA GALL Pauline Ann Ham 15 Hippisley Drive, Axbridge, HAM Somerset, BS26 2DE Barry Edward Hamblin 40 West Street, Axbridge, Somerset, HAMBLIN BS26 2AD Val Isaac Vine Cottage, 50 West Street, ISAAC Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2AD James A H Lukins Retired Farmer Townsend House, Axbridge LUKINS Andrew Robert Matthews The Cottage, Horns Lane, Axbridge, MATTHEWS Somerset, BS26 2AE Paul Leslie Passey Somerhayes, Jubilee Road, Axbridge, PASSEY Somerset, BS26 2DA Elizabeth Beryl Scott Moorland Farm, Axbridge, Somerset, SCOTT BS26 2BA Michael Taylor Mornington House, Compton Lane, TAYLOR Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2HP Jennifer Mary Trotman 4 Bailiff's -

East Huntspill - Mendips

March 2019 Area 3: East Huntspill - Mendips. Hinkley Connection Project. We are responsible for providing eabank safe, efficient and reliable energy networks across England and Wales. ortishead We are building a new high-voltage electricity connection between Avonmouth Bridgwater and Seabank near Avonmouth to connect new sources Bristol of power in the area, including Hinkley Point C, EDF Energy’s new Nailsea nuclear power station in Somerset, to UK homes and businesses. The new connection will be 57 km long – consisting of 48.5 km of overhead line and 8.5 km of underground cable through the Mendip Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Weston-super-Mare hurchill To minimise the impact on the local landscape and make way for the andford new connection, we are removing over 67 km of existing overhead lines and pylons. We will also build a new substation at Sandford and Shurton, modify the existing overhead lines at Hinkley Point and Seabank, extend Area 3 Seabank substation, and make some changes to the existing local electricity network owned by Western Power Distribution (WPD). Hinkley oint key This leaflet is one of a series of briefing sheets summarising the project. Existing overhead line New overhead The connection and associated infrastructure works will line take around eight years to build, including reinstatement and New underground replacement planting. cable Bridgwater Substation Build and access temporary Build 400,000 volt overhead line construction compounds We are building a new overhead line Vegetation clearance, replacement We need to build two temporary entrances, northwards from the existing Hinkley planting and reinstatement haul roads and compounds off the A38 at to Melksham overhead line north of We will need to clear some trees and Tarnock, to allow construction traffic to enter Woolavington to a new cable sealing end, hedgerows along the route of the new site from the local highway. -

New Slinky Sedge South L/Let V2.Indd 1 20/01/2017 14:58 Monday Pickup Area Tuesday Pickup Area Wednesday Pickup Area

What is the Slinky? How much does it cost? Slinky is an accessible bus service funded Please phone the booking office to check Sedgemoor South Slinky by Somerset County Council for people the cost for your journey. English National unable to access conventional transport. Concessionary Travel Scheme passes can be Your local transport service used on Slinky services. You will need to show This service can be used for a variety of your pass every time you travel. Somerset reasons such as getting to local health Student County Tickets are also valid on appointments or exercise classes, visiting Slinky services. friends and relatives, going shopping or for social reasons. You can also use the Slinky Somerset County Council’s Slinky Service is as a link to other forms of public transport. operated by: Mendip Community Transport, MCT House, Who can use the Slinky? Unit 10a, Quarry Way Business Park, You will be eligible to use the Slinky bus Waterlip, Shepton Mallet, Somerset BA4 4RN if you: [email protected] • Do not have your own transport www.mendipcommunitytransport.co.uk • Do not have access to a public bus service • Or have a disability which means you Services available: cannot access a public bus Monday to Friday excluding Public Holidays Parents with young children, teenagers, students, the elderly, the retired and people Booking number: with disabilities could all be eligible to use the Slinky bus service. 01749 880948 Booking lines are open: How does it work? Monday to Friday 9.30am to 4pm If you are eligible to use the service you will For more information on Community first need to register to become a member of Transport in your area, the scheme. -

East Huntspill Parish Housing Need Assessment

East Huntspill Parish Housing Need Assessment Review of the East Huntspill Housing Need Assessment December 2016 Reviewed December 2017 Review of East Huntspill December 2016 Housing Needs Assessment Published December 2016 Reviewed December 2017 Contact Duncan Harvey, Affordable Housing Policy and Development Manager Direct: 01278 436440 Email: [email protected] Esther Carter, Housing Project Development Officer Direct: 01278 435599 Email: [email protected] Organisation Sedgemoor District Council Address Affordable Housing Development Unit Housing, Health and Wellbeing Bridgwater House King Square Bridgwater Somerset TA6 3AR Telephone 0300 303 7800 Email [email protected] Sedgemoor The Sedgemoor District Council Affordable Housing Development Team (“AFHDT”) is a Affordable Housing small-dedicated team with specific responsibility to oversee the delivery of new affordable Development Team housing. The team are part of the wider SDC Strategy and Development Service. This service is responsible for developing and implementing many of the Council's key strategies and policies. Building upon a successful record of accomplishment of delivering affordable-homes in rural communities, the AFHDT provides support and advice to parish councils, landowners, developers and registered providers with the aim of developing new affordable-housing. The AFHDT has developed its own housing need assessment processes, which provide publically available independent and robust evidence for future housing growth in rural communities. Earlier 2016 East Huntspill Housing Need Assessment The following was recorded and reported in the December 2016 HNA report. Readers must remember that the conclusions within this report merely represent a snapshot in time into what (if any) unmet housing requirements exist in East Huntspill. -

WSCL 2021 Handbook

WEST SOMERSET CRICKET LEAGUE www.westsomersetcricket.co.uk 2021 PRESIDENT Mary Elworthy-Coggan, “Howzat”, Fitzhead, TA4 3JW. Tel: 01823 400679 VICE-PRESIDENTS Darby Ash, Richard Disney, Betty Lovell, Cliff Matravers, Roy Takle, David Wilson. CHAIRMAN Bob Bowyer, 37 Rodway Hill, Cannington, Bridgwater, TA5 2PJ Tel: 01278 652071; [email protected] VICE-CHAIRMAN Steve White, Myrtle House, Brook Street, North Newton, Bridgwater, TA7 0BN Tel: 01278 662694 / 07867 424054; [email protected] TREASURER & LORDS BALLS CO-ORDINATOR Dave Hingston, Coombe Lodge, Combeshead Cross, Chudleigh, Newton Abbot, TQ13 0NF Tel: 01626 853699 / 07542 071715; [email protected] SECRETARY & RECORDS OFFICER Caroline Stevenson, 59b Edward Street, Cannock, Staffordshire, WS11 5JF Tel: 07793 485682; [email protected] or [email protected] FIXTURES SECRETARY Gordon Everett, 26 Mountway Road, Bishops Hull, Taunton, TA1 5LS Tel: 01823 279610; [email protected] UMPIRES’ ORGANISER Stuart Allbut, 62 Parkfield Road, Taunton, TA1 4SD Tel: 01823 279918; [email protected] WEBSITE ADMINISTRATOR Tony Berthon, 1 Summerleaze Crescent, Taunton, TA2 8QE Tel: 01823 366067; [email protected] DIVISIONAL REPRESENTATIVES All queries and complaints should in the first instance be sent by email as early as possible to one of the divisional representatives, and not to any other member of the committee. The representative will either be able to deal with the matter directly, or will pass it on to the relevant sub-committee. The telephone should only be used in an emergency, but the later the problem is raised, the less chance there is of an immediate solution. Please note that proof of insurance must also be sent to your league representative before the start of the season. -

Situation of Polling Stations Bridgwater and West Somerset

The situation of the Polling Stations and the descriptions of the persons entitled to vote at each station are set out below: PD Polling Station and Address Persons entitled to vote at that station BAA 1 / BAA The Committee Room, Ashcott Village Hall, High Street, Ashcott, Bridgwater, Somerset, 1 to 976 TA7 9PZ BAB 2 / BAB Bawdrip Village Hall, East Side Lane, Bawdrip, TA7 8QB 1 to 460 BAC 3 / BAC Dunwear House, Communal Hall, Westonzoyland Road, Bridgwater, TA6 5BP 1 to 1610 BAD 4 / BAD Dunwear House, Communal Hall, Westonzoyland Road, Bridgwater, TA6 5BP 1 to 1986 BAE 5 / BAE The Railway Club, Wellington Road, Bridgwater, TA6 5HA 1 to 1729 BAF 6 / BAF Eastover Youth and Community Centre, All Saints Terrace, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA6 5JQ 1 to 1667 BAG 7 / BAG Sydenham Community Centre, Parkway, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA6 4QZ 1 to 1744 BAH 8 / BAH (PART 1),Sydenham Community Centre, Parkway, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA6 4QZ 1 to 1776 BAH 9 / BAH (PART 2),Sydenham Community Centre, Parkway, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA6 4QZ 1777 to 3551 BAI 10 / BAI Holy Trinity Church Hall, Hamp Street, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA6 6AR 1 to 1740 BAI 11 / BAI, BBK, Holy Trinity Church Hall, Hamp Street, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA6 6AR 1741 to 3558 BAJ 12 / BAJ Victoria Park Comm Centre, Victoria Park Drive, Bridgwater, Somerset 1 to 1338 BAJ 13 / BAJ Victoria Park Comm Centre, Victoria Park Drive, Bridgwater, Somerset 1339 to 3050 BAK 14 / BAK The Charter Hall, Town Hall, High Street, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA6 3AS 1 to 1602 BAL 15 / BAL Westfield United Reformed Church, West Street, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA6 7EU 1 to 1249 BAM 16 / BAM The Charter Hall, Town Hall, High Street, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA6 3AS 1 to 1237 BAN 17 / BAN Aspen Court Commuall Hall, Communal Hall, Aspen Court, Wembdon Road, Bridgwater, 1 to 2070 TA6 7EN BAO 18 / BAO, BAY, St. -

Coms Visited

COMMUNITIES SERVED BY SOMERSET MOBILE LIBRAIRIES Village Mobile Route Village Mobile Route A Butleigh Wootton WIN D Alcombe WIL K C Alford WIN B Allerford WIL B Cannington BRW B Alvington WIN P Carhampton WIL M Ashbrittle TAU B Catcott BRW M Ashcott BRW E Chaffcombe TAU H Ashford WIL L Chantry BRW Q Ashill TAU A Chapel Allerton BRW P Axbridge WIN G Charlton Adam WIN D Charlton Horethorne WIN H B Charlton Mackrell WIN D Charlynch WIL L Babcary WIN K Chedzoy BRW L Badgworth BRW P Chewton Mendip WIN I Bagley WIN G Chilcompton WIN I Baltonsborough WIN K Chillington TAU H Barrington WIN F Chilthorne Domer WIN P Barton St. David WIN D Chilton Polden BRW M Barwick WIN L Chipstable WIL I Bathealton TAU B Chiselborough WIN O Bawdrip BRW F Churchinford TAU L Beercrocombe WIN F Churchstanton TAU E Benter WIN I Cocklake WIN G Berrow BRW C Coleford WIN B Bicknoller WIL H Combe St. Nicholas TAU I Biddisham BRW P Combwich BRW B Binegar (Gurney Slade / Binegar) WIN I Combwich WIL E Bishop's Hull BRW K Compton Bishop BRW G Bishop's Hull TAU C Compton Dundon WIN D Bishops Lydeard WIL J Cossington BRW M Blackbrook TAU I Cotford St. Luke BRW K Blagdon TAU D Cothelstone WIL J Blue Anchor WIL M Courtway WIL E Bower Manor TAU J Coxley Wick BRW E Bradford-on-Tone TAU C Creech Heathfield TAU D Brean BRW C Creech St. Michael BRW H Brendon Hills WIL A Croscombe BRW Q Brent Knoll BRW F Cross BRW G Brent Knoll TAU J Crowcombe WIL J & N Bridgehampton WIN E Crowcombe Heathfield WIL N Bridgwater Children's Centres BRW L Cudworth TAU H Bridgwater (King's Down Village) BRW F Curload BRW H Bridgwater (Wilstock Village) WIL L Curry Mallet TAU F Broadway TAU A & F Curry Rivel BRW A Brompton Ralph WIL I Curry Rivel TAU M Brompton Regis BRW O Cutcombe BRW I Brompton Regis WIL C Broomfield WIL E D Brushford WIL G Buckland St.