A Consideration of Somerset's Holocene Environments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messenger May 2021 50P

Q U A N T O C K C O T N A U Q for Nether Stowey & Over Stowey & Over Stowey for Nether Messenger May 2021 50p 1 Belinda’s Soft Toys Sadly, Belinda Penn died at the beginning of March. Many of you will know Belinda had spent the past few years knitting favourite characters to raise funds for Dementia Care. PLEASE HELP to continue to raise funds in buying the toys which are on sale in the Library and Post Office at a very reasonable price of £5 and £8. I have many more toys which can be viewed at my home. I thank you in anticipation of your support for this worthy cause and in memory of Belinda Penn. Contact: Tina 07761586866 Physical books of condolence in public places for HRH The Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh are not permitted under current Covid-19 rules. If you would like to express your condolences, this can be done online through the Parish Council website or written comments can be handed in at the Parish Council office and they will be entered in a local Book of Condolence. “Former Ageing Well Manager, Di Ramsay, with 88 year old yoga teacher Ivy Thorne. Di tragically lost her battle with cancer last year. She was an inspirational leader, who made a huge difference to the wellbeing of many older people in Somerset”. 2 CLUBS & SOCIETIES IN NETHER STOWEY & OVER STOWEY Allotment Association Over Stowey Rights of Way Group Bruce Roper 732 043 Richard Ince 733 237 Active Living Group Over Stowey Social Club Call 734 613 or 733 040; 733 151; 732 609 Sue Thomas 732 905 Coleridge Probus Club Over Stowey Tennis Court Philip Comer (01984) -

Quaternary of South-West England Titles in the Series 1

Quaternary of South-West England Titles in the series 1. An Introduction to the Geological Conservation Review N.V. Ellis (ed.), D.Q. Bowen, S. Campbell,J.L. Knill, A.P. McKirdy, C.D. Prosser, M.A. Vincent and R.C.L. Wilson 2. Quaternary ofWales S. Campbeiland D.Q. Bowen 3. Caledonian Structures in Britain South of the Midland Valley Edited by J.E. Treagus 4. British Tertiary Voleanie Proviflee C.H. Emeleus and M.C. Gyopari 5. Igneous Rocks of Soutb-west England P.A. Floyd, C.S. Exley and M.T. Styles 6. Quaternary of Scotland Edited by J.E. Gordon and D.G. Sutherland 7. Quaternary of the Thames D.R. Bridgland 8. Marine Permian of England D.B. Smith 9. Palaeozoic Palaeobotany of Great Britain C.]. Cleal and B.A. Thomas 10. Fossil Reptiles of Great Britain M.]. Benton and P.S. Spencer 11. British Upper Carboniferous Stratigraphy C.J. Cleal and B.A. Thomas 12. Karst and Caves of Great Britain A.C. Waltham, M.J. Simms, A.R. Farrant and H.S. Goidie 13. Fluvial Geomorphology of Great Britain Edited by K.}. Gregory 14. Quaternary of South-West England S. Campbell, C.O. Hunt, J.D. Scourse, D.H. Keen and N. Stephens Quaternary of South-West England S. Campbell Countryside Council for Wales, Bangor C.O. Hunt Huddersfield University J.D. Scourse School of Ocean Sciences, Bangor D.H. Keen Coventry University and N. Stephens Emsworth, Hampshire. GCR Editors: C.P. Green and B.J. Williams JOINT~ NATURE~ CONSERVATION COMMITTEE SPRINGER-SCIENCE+BUSINESS MEDIA, B.V. -

Saints, Monks and Bishops; Cult and Authority in the Diocese of Wells (England) Before the Norman Conquest

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 3 Issue 2 63-95 2011 Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen University of Bristol Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Costen, Michael. "Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 3, 2 (2011): 63-95. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol3/iss2/4 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Costen Saints, Monks and Bishops; cult and authority in the diocese of Wells (England) before the Norman Conquest Michael Costen, University of Bristol, UK Introduction This paper is founded upon a database, assembled by the writer, of some 3300 instances of dedications to saints and of other cult objects in the Diocese of Bath and Wells. The database makes it possible to order references to an object in many ways including in terms of dedication, location, date, and possible authenticity, and it makes data available to derive some history of the object in order to assess the reliability of the information it presents. -

Information Requests PP B3E 2 County Hall Taunton Somerset TA1

Information Requests PP B3E 2 Please ask for: David Boorer County Hall FOI Reference: 1526265 Taunton Direct Dial: 01823 359359 Somerset Email: [email protected] TA1 4DY Date: 30 August 2016 Mr Mike Newman Dear Mr Newman Freedom of Information Act 2000 I can confirm that the information you have requested is held by Somerset County Council. Your Request: Can you supply the amounts and recipients of grants from the Members Health & Wellbeing Scheme in the following wards: 1. Brent 2. Burnham-on-Sea North 3. Burnham-on-Sea South and Highbridge 4. Huntspill For: a. The 2015/16 financial year b. The 2016/17 financial year to date Our Response: I have detailed below the information that Somerset County Council hold. This information is for the financial year 2015/16. The Health and Wellbeing Scheme is not running for this financial year, 2016/17. Beneficiary Purpose Amount Brent N/A N/A Burnham-On-Sea, Sensational Kids £2,000.00 North Sensory Room Music for the Memory £2,000.00 Sedgemoor Play Day £1,000.00 Burnham-On-Sea, Red Bowls Club. £100.00 South & Highbridge Replace player boards Autism Somerset CiC. £3,500.00 Cover the cost of training, childcare cost, lunch, travel, room hire. Huntspill Puriton Parish Council. £750.00 Re-erect the old phone box Puriton Parish Council. £500.00 Over 60's club, including meals. Cossington Parish £800.00 Council. Purchase and install a bench in play area. Woolavington Parish £750.00 Council. Security cameras for village hall. East Huntspill Parish £1,000.00 Council. -

New Colleges L/Let.Indd

Town/Village Service number Town/Village Service number Aller 16 Norton Fitzwarren 613 Ashcott 75 Othery 16 Guide to buses serving Axbridge 66 Pawlett 21,62 Banwell 62 Puriton 66,75,X75 Berrow 21 Rockwell Green 623 Bishops Lydeard 613 Rooksbridge 21, 62 Bridgwater & Blackford 66 Shurton 14 Burnham-on-Sea 21 Sidcot 62 Burton 14 Spaxton 613 Taunton College Cannington 14,15,16,623,625 Stawell 19 Catcott 75 Stockland Bristol 14 Bridgwater Campus Chard 624 Stogursey 14 Cheddar 66 Street 75,X75 Academic Year 2019-20 Chedzoy 19 Sutton Mallet 19 Cocklake 66 Taunton 625 Combwich 14 Washford 15 Cossington 75 Watchet 15 Cotford St Luke 613 Wedmore 66 Dunball 21,75 Wellington 623 Durleigh 613 Wells X75 East Brent 21 Wembdon 14, 15 East Huntspill 66 West Huntspill 21 Enmore 613 Weston-Super-Mare 62 Glastonbury X75 West Quantoxhead 15 Goathurst 613 Westonzoyland 16 Greinton 19 Williton 15 Hawkridge Reservoir 613 Woolavington 66,75,X75 Highbridge 21,62 Holford 15 Bakers Dolphin Huish Episcopi 16 Weston - Highbridge - Bridgwater 62 Ilminster 624 Axbridge - Cheddar - East Huntspill - Bridgwater 66 Kilve 15 Buses of Somerset Kingston St Mary 613 Shurton - Bridgwater 14 Langport 16 Minehead - Bridgwater 15 Locking 62 Greinton - Moorlynch - Chedzoy - Bridgwater 19 Mark 66 Rooksbridge - Bridgwater 21 Middlezoy 16 Wells - Street - Glastonbury - Bridgwater 75/X75 Minehead 15 Rockwell Green - Wellington - Bridgwater College - Monkton Heathfield 623,625 Cannington College 623 Moorlinch 19 Taunton - Bridgwater College - Cannington College Nether Stowey 15 625 North -

Warren Road, Brean, Somerset Gth.Net the Highway Warren Road, Brean, Somerset TA8 2RR

The Highway (and adjacent Building Plot), Warren Road, Brean, Somerset gth.net The Highway Warren Road, Brean, Somerset TA8 2RR Burnham-on-Sea: 5 Highbridge: 7 miles; Weston-Super- Mare: 10 miles This good size, mature, 3 bedroom and 2 loft room, detached bungalow occupies a large plot with the considerable benefit of an attached building plot (with permission for the erection of a detached dwelling and garage) together with a mature rear garden with stunning coastal views across to the Welsh coast, no onward chain offered. Guide Price £450,000 Description This detached, mature, dormer-style bungalow was believed to have been built in the 1930’s (with later additions) occupying an elevated, good size plot backing onto the beach near Brean Down offering super sea views. The property further benefits from full planning permission to construct a detached dwelling adjacent to the property (the agent can provide a planning pack if so desired). Sedgemoor No: 06/19/00008. The property accommodation comprises: entrance hallway, living room, conservatory, kitchen/dining room (with utility), rear lobby with shower-room, garden room, 3 bedrooms and a bathroom. On the dormer level are 2 loft rooms and a shower room. AGENTS NOTE Further benefits include oil fired central heating, UPVC double glazed It would be fair to say that the property could benefit from updating and windows, cooker set to remain, and all fitted carpets, curtains and blinds modernisation. are also set to remain. Situation Externally the property occupies a large, mature plot. The current Vendors The property is situated in the coastal village of Brean within a short stroll have obtained full planning permission to erect a detached dwelling and of the Brean Down Inn and the beach. -

Circular Oct 05.Pages

Quaternary Research Association Registered Charity no: 262124 OCTOBER 2005 CIRCULAR CONTENTS 1. QRA Administration 2. Proposed new members of the Executive Committee 3. Outreach activities: request for information 4. QRA Membership List Reminder 5. Quaternary Newsletter 6. Inaugural meeting of the British Permafrost and Periglacial Association, 14th December 2005. 7. Annual Discussion Meeting, University of Glasgow, 5th-6th January 2005, ‘Isotope (Radiogenic, Cosmogenic and Stable) and Noble Gas Analysis in Quaternary Research’ 8. Annual Field Meeting and AGM, Somerset, 2nd-7th April 2006 9. Joint meeting with the British Geomorphological Research Group on Geomorphology and Earth System Science, 28th-30th June 2006, University of Loughborough 10. Geoarchaeology 2006, University of Exeter, 12th-15th September 2006 11. Group Manche meeting, Cenozoic history of the English Channel, University of Southampton, 14th-17th september 2006 12. QRA Research and Conference Grants 13. Journal of Quaternary Science 14. Quaternary Science Reviews, The Holocene and Boreas 15. Calendar of QRA Meetings QRA CIRCULAR: October 2005 1. QRA ADMINISTRATION The Executive Committee has been struggling for a few years now to maintain efficient systems for membership subscriptions and publications. We are therefore delighted that we have been able to appoint Valerie Siviter as the QRA Administrator. She is already handling publications orders and dealing with the regular mailing of Quaternary Newsletter and the Circular. In due course she will also look after the membership database. Val can be contacted at [email protected]. Please send all orders for publications to Val. Alterations to membership details should continue to go to Jen Heathcote ([email protected]) for the time being. -

Puriton Energy Park SPD March 2012

Puriton Energy Park Supplementary Planning Document (Adopted 28th March 2012) Chapter 1 Introduction 1.1 Status of Document 1.2 Purpose of the SPD Chapter 2 Strategic and Local Context 2.1 Strategic Context 2.2 Local Context Chapter 3 The Site 3.1 Historic Use 3.2 Scale and Character 3.3 Site Access 3.4 Current Position 3.5 Landscape Context Chapter 4 Planning Policy Context 4.1 Policy Context 4.2 Regional Spatial Strategy for the South West 4.3 Somerset and Exmoor national Park Joint Structure Plan Review (1991-2011) 4.4 Somerset Economic Assessment (March 2011) 4.5 Sedgemoor Economic Masterplan (2008-26) 4.6 Bridgwater Vision 4.7 Sedgemoor Core Strategy (2006-27) Policy S1: Spatial Strategy Policy MIP1: Major Infrastructure Proposals Policy D11: Economic Prosperity Policy P1: Bridgwater Urban Area Policy D2: Promoting High Quality and Inclusive Design Policy D4: Renewable or Low Carbon Energy Generation Other Relevant Policies (S2, S3, S4, MIP 1, D1, D3, D9, D10, D14, D16, D17, D19, D20, D21) 4.8 Sustainable Community Strategy for Sedgemoor (2009) 4.9 Sedgemoor Corporate Strategy (2009-14) 4.10 Sedgemoor Climate Change Strategy (draft 2012) 4.11 Sedgemoor Green Infrastructure Strategy (2011) 4.12 Sedgemoor Landscape Assessment (2003) 4.13 Somerset Waste Core Strategy (draft 2012) Chapter 5 Site Analysis 5.1 Principle of Redevelopment 5.2 Site Benefits and Constraints 5.3 Brownfield and Greenfield 5.4 Flood Risk 5.5 Biodiversity and Ecology 5.6 Transport and Accessibility Chapter 6 The Energy Park Concept 6.1 Defining the Energy -

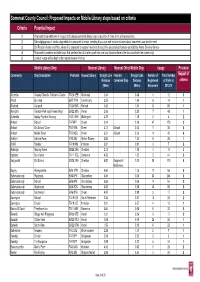

Consultation List of Mobile Stops and Potential Impact.Xlsx

Somerset County Council: Proposed Impacts on Mobile Library stops based on criteria Criteria Potential Impact 1 Proposed to be withdrawn in August 2015 because mobile library stop is less than 3 miles from a library building 2 School/playgroup or similar stop which it is proposed to retain, pending discussion with each institution about how needs can best be met 3 Old People's home or similar, where it is proposed to support residents through the personalised service provided by Home Delivery Service 4 Proposed to combine multiple stops that are less than 0.5 miles apart into one stop (location/time to be discussed with the community) 5 Level of usage will be kept under regular review in future Mobile Library Stop Nearest Library Nearest Other Mobile Stop Usage Potential Community Stop Description Postcode Nearest Library Straight Line Possible Straight Line Number of Total Number impact of Distance Combined Stop Distance Registered of Visits in criteria (Miles) (Miles) Borrowers 2013/14 Alcombe Cheeky Cherubs Children’s Centre TA24 5EB Minehead 0.64 0.38 1 12 2 Alford Bus stop BA7 7PWCastle Cary 2.05 1.44 6 19 1 Allerford Car park TA24 8HSPorlock 1.36 1.01 8 80 1 Alvington Fairacre Park (opp Fennel Way) BA22 8SA Yeovil 2.06 0.20 7 48 1 Ashbrittle Appley Pavillion Nursery TA21 0HH Wellington 4.22 1.18 2 4 2 Ashcott School TA79PP Street 3.04 0.18 47 179 2 Ashcott Old School Close TA7 9RA Street 3.12 Ashcott 0.13 11 35 4 Ashcott Middle Street TA7 9QG Street 3.01 Ashcott 0.13 14 45 4 Ashford Ashford Farm TA5 2NL Nether Stowey 2.86 1.10 6 -

Converted from C:\PCSPDF\PCS52117.TXT

M127-7 SEDGEMOOR DISTRICT COUNCIL CANDIDATES SUMMARY PARISH COUNCIL ELECTION - 3RD MAY 2007 Area Candidates Party Address Parish of Ashcott Adrian Scot Davis 20 School Hill, Ashcott, Somerset, DAVIS TA7 9PN Number of Seats : 8 Cilla Ann Thurlow Grain Ashcott Resident 3 Pedwell Lane, Ashcott, Bridgwater, GRAIN Somerset, TA7 9PD Joe Jenkins Saddle Stones, 31 Pedwell Hill, JENKINS Ashcott, Bridgwater, Somerset, TA7 9BD Jenny Lawrence 3 The Batch, Ashcott, Bridgwater, LAWRENCE Somerset, TA7 9PG Jack Miles Sayer 29 High Street, Ashcott, Bridgwater, SAYER TA7 9PZ Axbridge Town Council Dennis Bratt Past Mayor of Axbridge 62 Knightstone Close, Axbridge, BRATT Somerset, BS26 2DJ Number of Seats : 13 Kate Walker Independent 36 Houlgate Way, Axbridge, Somerset, Browne BS26 2BY BROWNE Christopher Byrne Wavering Down, Webbington Road, BYRNE Cross, Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2EL Jeremy Gall 6 Moorland St, Axbridge, BS26 2BA GALL Pauline Ann Ham 15 Hippisley Drive, Axbridge, HAM Somerset, BS26 2DE Barry Edward Hamblin 40 West Street, Axbridge, Somerset, HAMBLIN BS26 2AD Val Isaac Vine Cottage, 50 West Street, ISAAC Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2AD James A H Lukins Retired Farmer Townsend House, Axbridge LUKINS Andrew Robert Matthews The Cottage, Horns Lane, Axbridge, MATTHEWS Somerset, BS26 2AE Paul Leslie Passey Somerhayes, Jubilee Road, Axbridge, PASSEY Somerset, BS26 2DA Elizabeth Beryl Scott Moorland Farm, Axbridge, Somerset, SCOTT BS26 2BA Michael Taylor Mornington House, Compton Lane, TAYLOR Axbridge, Somerset, BS26 2HP Jennifer Mary Trotman 4 Bailiff's -

East Huntspill - Mendips

March 2019 Area 3: East Huntspill - Mendips. Hinkley Connection Project. We are responsible for providing eabank safe, efficient and reliable energy networks across England and Wales. ortishead We are building a new high-voltage electricity connection between Avonmouth Bridgwater and Seabank near Avonmouth to connect new sources Bristol of power in the area, including Hinkley Point C, EDF Energy’s new Nailsea nuclear power station in Somerset, to UK homes and businesses. The new connection will be 57 km long – consisting of 48.5 km of overhead line and 8.5 km of underground cable through the Mendip Hills Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). Weston-super-Mare hurchill To minimise the impact on the local landscape and make way for the andford new connection, we are removing over 67 km of existing overhead lines and pylons. We will also build a new substation at Sandford and Shurton, modify the existing overhead lines at Hinkley Point and Seabank, extend Area 3 Seabank substation, and make some changes to the existing local electricity network owned by Western Power Distribution (WPD). Hinkley oint key This leaflet is one of a series of briefing sheets summarising the project. Existing overhead line New overhead The connection and associated infrastructure works will line take around eight years to build, including reinstatement and New underground replacement planting. cable Bridgwater Substation Build and access temporary Build 400,000 volt overhead line construction compounds We are building a new overhead line Vegetation clearance, replacement We need to build two temporary entrances, northwards from the existing Hinkley planting and reinstatement haul roads and compounds off the A38 at to Melksham overhead line north of We will need to clear some trees and Tarnock, to allow construction traffic to enter Woolavington to a new cable sealing end, hedgerows along the route of the new site from the local highway. -

Download Original Attachment

Properties over 30K Account................. Property................ Property.. Current. Holder Address Postcode RV Ashcott Primary School ASHCOTT PRIMARY SCHOOL TA7 9PP 30250 RIDGEWAY ASHCOTT BRIDGWATER SOMERSET Consumer Buyers Ltd T/a CHURCH FARM STATION ROAD TA7 9QP 42250 Living Homes ASHCOTT BRIDGWATER SOMERSET Butcombe Brewery Ltd THE LAMB INN THE SQUARE BS26 2AP 38000 AXBRIDGE SOMERSET Sustainable Drainage CLEARWATER HOUSE BS26 2RH 53500 System Ltd CASTLEMILLS BIDDISHAM AXBRIDGE SOMERSET The Environment Agency BRADNEY DEPOT BRADNEY TA7 8PQ 56500 LANE BAWDRIP BRIDGWATER SOMERSET Burnham & Berrow Golf BURNHAM & BERROW GOLF TA8 2PE 144000 Club Limited CLUB ST CHRISTOPHERS WAY BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET Berrow Primary School BERROW PRIMARY SCHOOL TA8 2LJ 49750 RUGOSA DRIVE BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET Brightholme Caravan Park BRIGHTHOLME CARAVAN PARK TA8 2QY 46250 Ltd COAST ROAD BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET John Fowler Holidays SANDY GLADE HOLIDAY PARK TA8 2QR 236500 Limited COAST ROAD BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET Unity Farm Holiday HOLIDAY RESORT UNITY TA8 2QY 818500 Centre Ltd COAST ROAD BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET The Caravan Club Limited THE CARAVAN CLUB HURN TA8 2QT 43100 LANE BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET Flamingo Park Limited ANIMAL FARM COUNTRY PARK TA8 2RW 37500 RED ROAD BERROW BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET Brean Down Caravan Park BREAN DOWN CARAVAN PARK TA8 2RS 47500 Ltd BREAN DOWN ROAD BREAN BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET A G Hicks Ltd NO 1 CARAVAN SITE TA8 2SF 71000 SOUTHFIELD FARM CHURCH ROAD BREAN BURNHAM ON SEA SOMERSET