Global Media Journal - Australian Edition - 6:1 2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1968 Cams Australian Rally Championship

1968 CAMS AUSTRALIAN RALLY CHAMPIONSHIP THE EVENTS The 1968 CAMS Australian Rally Championship: 1 Classic Rally Victoria GMH Motoring Club Kilfoyle/Rutherford 2 Snowy Rally New South Wales Australian Sorting Car Club Ferguson/Johnson 3 Walkerville 500 Rally South Australia Walkerville All Cars Club Firth/Hoinville 4 Canberra 500 Rally ACT Canberra Sporting Car Club Keran/Meyer 5 Warana Rally Queensland Brisbane Sporting Car Club Firth/Hoinville 6 Alpine Rally Victoria Light Car Club of Australia Roberts/Osborne FINAL POINTS 1 Harry Firth 25.5 1 Graham Hoinville 25.5 2 Frank Kilfoyle 19.5 2 Peter Meyer 19 3 John Keran 16 3 Doug Rutherford 16.5 4 Bob Watson 14 =4 Nigel Collier 14 5 Ian Vaughan 12 =4 Mike Osborne 14 6 Barry Ferguson 9 6 Dave Johnson 12 CAMS Manufacturers Award Not awarded The 1968 Championship winning Ford Cortina Lotus with Harry Firth and Graham Hoinville SUMMARY Australian rallying for 1968 constituted the hardest year of this branch of the sport any of the regular contestants had faced. Competition came from some twenty crews in superb vehicles – and those crews had some outstanding events in which to compete under the auspices of CAMS. Firstly, there was the inaugural Australian Rally Championship (ARC); secondly the Southern Cross International Rally; thirdly, the London to Sydney Marathon, which clashed with the last round of the Championship. The ARC was a series of six rallies conducted in four states, of which the best five scores counted for the final pointscore. First placed gained 9 points with the following five places earning 6, 4, 3, 2, 1, as was the common scoring system in circuit racing. -

Sydney – Port Macquarie - Sydney

Barry Ferguson/Dave Johnson in the Holden Torana GTR – from the 1971 regulations booklet 1970 7 - 11 OCTOBER SYDNEY – PORT MACQUARIE - SYDNEY 62 PREAMBLE The New South Wales tourist resort town of Port Macquarie became the host town to the 1970 Southern Cross International Rally, again directed by Alan Lawson. In between starting and finishing in Sydney, the event spent three nights at Port Macquarie, with its thousands of square miles of adjacent forests, ideal for the way rallying was developing now that shire roads were not readily available. The new area allowed for an event in excess of 3000 kilometres and was considered to be able to provide competition at least half as tough again as previous events, although 1969 was not considered to be as tough as the first three years, when the event passed through the Australian Capital Territory and Victoria. The Southern Cross International Rally was becoming a major undertaking, and one that brought rewards to entrants and competitors, and also to the commercial and tourist interests who supported it. With this kind of support, the event looked forward to be being Australia’s answer to some of the top overseas events. The starting order was by ballot within five categories, which unlike previous years, reflected the increasingly international status of the event. The first category was drivers who had placed up to 6th in an international rally. The second category was for drivers placed up to 12th in any international rally or up to 6th in a national championship rally. The third category was for drivers who had placed up to 3rd in class in an international rally or up to 12th in a national championship rally. -

Women in the Redex Around Australia Reliability Trials of the 1950S

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Arts - Papers (Archive) Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2011 The flip side: women in the Redex Around Australia Reliability Trials of the 1950s Georgine W. Clarsen University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Clarsen, Georgine W., The flip side: women in the Redex Around Australia Reliability Trials of the 1950s 2011, 17-36. https://ro.uow.edu.au/artspapers/1166 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The Flip Side: Women on the Redex Around Australia Reliability trials of the 1950s Georgine Clarsen In August 1953 almost 200 cars set off from the Sydney Showgrounds in what popular motoring histories have called the biggest, toughest, most ambitious, demanding, ‘no-holds-barred’ race, which ‘caught the public imagination’ and ‘fuelled the nation with excitement’.1 It was the first Redex Around Australia Reliability Trial and organisers claimed it would be more testing than the famous Monte Carlo Rally through Europe and was the longest and most challenging motoring event since the New York-to-Paris race of 1908.2 That 1953 field circuited the eastern half of the continent, travelling north via Brisbane, Mt Isa and Darwin, passing through Alice Springs to Adelaide and returning to the start point in Sydney via Melbourne. Two Redex trials followed, in 1954 and 1955, and each was longer and more demanding than the one before. -

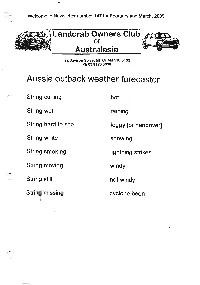

Aussie Outback Weather Forecaster

Welcome to Newsletter number 147 for February and March, 2009 ·.. ~a~ · ~.~ landcrab Owners Club Of ~~~~ Australasia 22 Davison Street MITCHAM VIC 3132 Ph 0398733038 Aussie outback weather forecaster -" ("' String curling hot String wet raining String hard to see foggy [or hangover] String white snowing String smoking lightning strikes String moving windy String still not windy ~missing Stri . cyclone been f1 THE WIND BAGS PRESIDENT Ian Davy 11 Oxley Cres Pabick Fa GOUlBURN NSW 2580 4 Wayne A e 0248226916 Borania Vic . 55 [email protected] 03 9762 4457:' [email protected] DATA REGISTRAR EDITOR I SECRETARY Peter Jones Daryl Stephens 4 Yarandin Court 22 Davison Street Worongary QLD 4211 Mitcham Vic 3132 0755748293 03 9873 3038 " [email protected] .au [email protected] PUBLIC OFFICER SOCIAL CONVENORS Peter Collingwood Brisbane: Peter Jones 18 Ughthorse Cres Narre Warren Vic 3804 Melbourne Nil 0397041822 Sydney Nil r Opinions expressed .within are not necessarily shared by the Editor or officers of the Club. While great care is taken to ensure that the technical information and advice offered in these pages is correct, the Editor and Officers of the Club cannot be held responsible for any problems that may ensure from acting on such advice and information. A Super idea by Daryl Stephens On the 21 st of November, 1965, the astonishing, outstanding Austin 1800 was released in the Sunburnt Country. BMC Australia claimed the 1800 was fully adapted to our harsh environment. Which was a load of hog wash!!?? The Morris 1100 experience had shown that engine mountings could be a problem. -

Rally Directions 2020 Issue 09 - September

September 2020 Issue 09 Dates to remember When we can go rallying again The official Organ of the Classic Rally Club Inc. Magazine deadline October 20 Rally Directions(Affiliated with C.A.M.S.) STOP PRESS BREAKING NEWS CRC GENERAL MEETING BACK ON ! SEPTEMBER MEETING 22nd SEPT 2020 NEW VENUE STRATHFIELD GOLF CLUB 52 Weeroona Road, Strathfield. Large new modern Covid compliant venue Two levels of undercover basement secure parking/ lifts to foyer to sign in. Bistro open from 5.30,reserved only for CRC people, $20 per head set menu, choice of meals/free tea and coffee with meal. Full Bar Service Turn the page to read about; John’s Jabber 1996 Even Green Memorial Rally First rally report in Rally Directions 1967 Launch of Morris 1100S by Des White John Bryson— A Rally Living Legend Notice Board by Jeff Whitten Sheep Wash Social Picnic Run Classic Rally Club Officers and Contacts 2020 Phone (please make calls before Position: Name email 9.00pm) President: John Cooper [email protected] 0414 246 157 Secretary: Tony Kanak [email protected] 0419 233 494 Treasurer: Peter Reed [email protected] 0418 802 972 Membership: Glenn Evans [email protected] 0414 453 663 Newsletter Editor: Chris McDonald [email protected] 0419 255 032 Competition Secretary: Ross Warner [email protected] 0409810553 Championship Pointscorer: Mike [email protected] 0400 174 579 Batten Historic Vehicle Plates: Ron Cooper [email protected] 0403 037 137 Webmaster: Harriet Jordan [email protected] Phone (please make calls before C.A.M.S. -

1 Modified: Cars, Culture and Event Mechanics Glen Robert Fuller Doctor of Philosophy

Modified: Cars, Culture and Event Mechanics Glen Robert Fuller Doctor of Philosophy - Cultural Histories and Futures University of Western Sydney 2007 © Glen Robert Fuller 2007 1 Dedication I dedicate this work to my parents, Robert and Jenny Fuller, for allowing me to make my own mistakes. I have made plenty of mistakes but this has allowed me to find my own challenges in the world. They supported me through every challenge and without their support this work would not be possible. My brother and sister, Paul and Clare Fuller, have supported me with a critical strength that only siblings know and helped me cope with being away from my family. Every time I returned home, I felt like I was returning home. I thank Samantha, Kirsten and Amanda for surprising me with love and life. They were burdened with my distracted solitude and yet all gave their love with an impossible grace. Samantha taught me how to compose myself in a gentle manner and accept change. Kirsten helped me grow up and made me realise I was actually living in Sydney. Lastly, when lost in the anxieties of work and relationships, Amanda forced me to accept the flaws and responsibilities of being only human. To all my other friends, particularly those I correspond with through weblogs, the other postgraduate students from the Centre for Cultural Research and Cultural Studies Association of Australasia, and my old friends from Perth, thanks for keeping the world sane. For all the car nuts who allowed me to be part of their scene, I thank you. -

1966 Have Been the Biggest Ever, with Principal ‘Works’ Teams Doing Battle in Almost Every State

“Trials in Australia in 1966 have been the biggest ever, with principal ‘works’ teams doing battle in almost every state. Culmination of this highly exciting branch of the Sport will be the International Southern Cross Rally in October. Article David Atkinson has presented a scene we may expect to see somewhere along the route. Reprints are available at 10 cente per copy” 1966 5 – 9 OCTOBER SYDNEY – MELBOURNE - SYDNEY Compiled by Tom Snooks, October 2016; email: [email protected] Southern Cross International Rally 1966 F 1 PREAMBLE The Southern Cross International Rally was organised by the Australian Sporting Car Club (ASCC), based in Sydney. The club organised the Redex Trials (1953-1955) and Ampol Trials of 1956, 1957, 1958 and 1964. The event was conducted in early October, starting on the Thursday and taking in the weekend after the Bathurst touring car race. This started in 1966, when the Bathurst race (the Gallaher 500), attracted international drivers who competed at Bathurst in Morris Mini Cooper S cars under the BMC banner headed by Gus Staunton – Paddy Hopkirk (dnf in the race) and Rauno Aaltonen (who won the race) - to also take part in the newly introduced Southern Cross International Rally. SUMMARY Winners are grinners – Harry Firth and Graham Hoinville The inaugural ‘Southern Cross’ Rally in 1966, directed by Bob Selby-Wood, brought classic international rallying to Australia. Attracting 69 starters, including European stars Paddy Hopkirk and Rauno Aaltonen in their state-of-the- art Cooper S cars, the 3500 kilometre event ran from Sydney to Melbourne and back, via Canberra. -

Rally Directions 2015 Issue 02

RallyRally DirectionsDirectionsThe official Organ of the Classic Rally Club Inc. February 2015 In this issue: Geoff Owens had a run in the Twilight Rallysprints at S.M.P. in his Datsun 260Z with Vince Harlor navigating. Dave Oliver of DOPHOTO.com.au took this great photo of the Datto as well as the others of the event in this issue. Also inside we have details of our Rally Legend John Bryson’s exploits and all you need to know about Chev. Corvettes, along with coverage of the CRC Training Day and more. Upcoming events: Saturday 28th February 2015. Highway 31 Revisited. Our first (Full details inside) Championship event of the year is a one dayer starting and finishing in Mittagong. Enjoy all the usual features of a CRC rally as you explore the old Hume Highway. Tony Norman will accept late entries up until the Club meeting on Tuesday 24th February. Sunday 29th March 2015. Wollondilly 300. A new event on our calendar from Mike Batten and his crew. Start in Penrith, finish at Sutton Forest. Masters, Apprentice, Tour and Social Run categories with no unsealed roads for Tour & Social Run & less than 2.0 km of good dirt for the rest of the field. Classic Rally Club Officers and Contacts 2015 Phone (please make calls before Position: Name email 9.00pm) President: John Cooper [email protected] 0414 246 157 Secretary: Tony Kanak [email protected] 0419 233 494 Treasurer: Tim McGrath [email protected] 0419 587 887 Membership: Glenn Evans [email protected] 0414 453 663 Newsletter Editor: -

160MPH “SUPER CARS” SOON. Minister Horrified by the Sun –Herald Motoring Editor EVAN GREEN Australia's Three Major Car M

160MPH “SUPER CARS” SOON. Minister Horrified By the Sun –Herald Motoring Editor EVAN GREEN Australia’s three major car makers are about to produce ‘super cars” with top speeds up to 160 miles an hour. But NSW transport minister Milton Morris said yesterday that he was appalled at “bullets on wheels” being sold to ordinary motorists. The automotive “big three” General Motors Holden, Ford and Chrysler are building the cars for a head on confrontation in Australia’s most important motor race, the Hardie Ferodo 500, at Bathurst on October 1. The cars will be available to the general public for use on the open road. Bitter Controversy. SUPER CARS HORRIFY TRANSPORT MINISTER The new models, developed from family saloons, are among the fastest and most powerful cars in the world. Their introduction is sure to arouse bitter controversy. The “super cars”are : A V8 Holden Torana, which will replace the 6 cylinder XU1 as GMH’s top competition car. With it’s light body and big engine, it is potentially the fastest car ever built in this country, with a theoretical top speed in excess of 160mph. Australia’s most powerful car, the 380 bhp Ford Falcon GTHO Phase 4, which is capable of sustaining a maximum speed of 152mph, but is expected to go faster on the down hill straight at Bathurst. An updated version of the Chrysler Valiant Charger, with a high performance 6 cylinder engine developing almost 300bhp, and a new 4 speed close ratio gearbox. The new Chrysler is already in production. Two of the 4 speed Chargers known as the E39 (incorrect this is E49) series will be racing at Oran Park today in the models competition debut. -

1966 Southern Cross International Rally Winners Harry Firth/Graham Hoinville in Their Ford Cortina GT Mk1 - from the Cover of the 1967 Supplementary Regulations

1966 Southern Cross International Rally winners Harry Firth/Graham Hoinville in their Ford Cortina GT Mk1 - from the cover of the 1967 Supplementary Regulations 1966 5 – 9 OCTOBER SYDNEY – MELBOURNE - SYDNEY 14 PREAMBLE The Southern Cross International Rally was organised by the Australian Sporting Car Club (ASCC), based in Sydney. The club organised the Redex Trials (1953-1955) and Ampol Trials of 1956, 1957, 1958 and 1964. The event was conducted in early October, starting on the Thursday and taking in the weekend after the Bathurst touring car race. This started in 1966, when the Bathurst race (the Gallaher 500), attracted international drivers who competed at Bathurst in Morris Mini Cooper S cars under the BMC banner headed by Gus Staunton – Paddy Hopkirk (dnf in the race) and Rauno Aaltonen (who won the race) - to also take part in the newly introduced Southern Cross International Rally. Start Order The start order was determined by public ballot, conducted within five categories of drivers: Category 1 Drivers who had finished up to an including sixth outright in an international rally; Category 2 Drivers who finished up to and including 12th in an international rally; or up to and including sixth in a national championship rally; Category 3 Drivers placed up to and including third in class classification in an international rally or up to and including 12th in a national championship rally; Category 4 Drivers who had completed the course of an international rally or a rally of national championship status; Category 5 Drivers not classified in Categories 1 to 4 above. -

Club Veedub Sydney. October 2016

NQ629.2220994/5 Club VeeDub Sydney. www.clubvw.org.au Barry Ferguson, VW 1200, Bathurst 1963 October 2016 IN THIS ISSUE (Guest-edited by STEPHANIE SCHENK): Barry Ferguson interview Sydney German Autofest ACT German Auto Display Canley Heights car show Norm’s VIC report Jim’s eventful Valla trip From our Website Plus lots more... Club VeeDub Sydney. www.clubvw.org.au A member of the NSW Council of Motor Clubs. Also affiliated with CAMS. ZEITSCHRIFT - October 2016 - Page 1 Club VeeDub Sydney. www.clubvw.org.au Club VeeDub Sydney Club VeeDub membership. Membership of Club VeeDub Sydney is open to all Committee 2016-17. Volkswagen owners. The cost is $45 for 12 months. President: Steve Carter 0490 020 338 [email protected] Monthly meetings. Monthly Club VeeDub meetings are held at the Arena Vice President: David Birchall (02) 9534 4825 Sports Club Ltd (Greyhound Club), 140 Rookwood Rd, [email protected] Yagoona, on the third Thursday of each month, from 7:30 pm. All our members, friends and visitors are most welcome. Secretary and: Norm Elias 0421 303 544 Membership: [email protected] Correspondence. Treasurer: Martha Adams 0404 226 920 Club VeeDub Sydney [email protected] PO Box 1340 Camden NSW 2570 Editor: Phil Matthews 0412 786 339 [email protected] Flyer Designer: Lily Matthews Our magazine. Zeitschrift (German for ‘magazine’) is published monthly Webmasters: Aaron Hawker 0413 003 998 by Club VeeDub Sydney Inc. We welcome all letters and [email protected] contributions of general VW interest. These may be edited for reasons of space, clarity, spelling or grammar. -

1969 Cams Australian Rally Championship

1969 CAMS AUSTRALIAN RALLY CHAMPIONSHIP THE EVENTS The 1969 CAMS Australian Rally Championship: 1 Classic Rally Victoria GMH Motoring Club Kilfoyle/Rutherford 2 Snowy Rally New South Wales Australian Sporting Car Club Green/Denny 3 Winter Trial South Australia VW Car Club Callary/Chapman 4 Warana Rally Queensland Brisbane Sporting Car Club Kilfoyle/Rutherford 5 Alpine Rally Victoria Light Car Club of Australia Kilfoyle/Rutherford FINAL POINTS 1 Frank Kilfoyle Vic 27 1 Doug Rutherford Vic 27 2 John Keran NSW 14 2 Peter Meyer NSW 14 3 Tony Roberts Vic 12 3 Brian Hope NSW 11 4 Ian Vaughan Vic 11 4 Bob Forsyth Vic 11 5 Evan Green NSW 10 5 Roy Denny NSW 10 6 Adrian Callary SA 9 6 Garry Chapman Vic 9 Manufacturers Award Ford Motor Co of Australia 1969 Australian Rally Champions – Frank Kilfoyle/Doug Rutherford in the Ford Cortina Lotus SUMMARY After the success of the inaugural Australian Rally Championship in 1968, which brought together at differing times the best of competitors from most of the states (Western Australia and Tasmania excluded), there was a yearning for a continuation of the championship. New South Wales had a clouded rally situation, with CAMS representatives working in the background to find answers to Police requirements that permissions to use roads be obtained from each Shire Council along the route of every rally. This situation was brought about by complaints from country-dwellers about the speeds and so-called reckless driving of those involved in rallies and could lead to areas being banned to rallying. There was also talk about General Motors disbanding its highly successful rally team, and this ended up with the development of the very successful Holden Dealer Team under Harry Firth.