How to Develop Disability Awareness Using the Sport Education Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

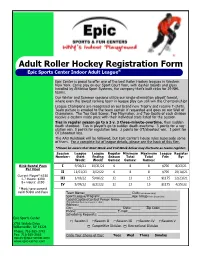

Inline Hockey Registration Form

Adult Roller Hockey Registration Form Epic Sports Center Indoor Adult League® Epic Center is proud to offer one of the best Roller Hockey leagues in Western New York. Come play on our Sport Court floor, with dasher boards and glass installed by Athletica Sport Systems, the company that’s built rinks for 29 NHL teams. Our Winter and Summer sessions utilize our single-elimination playoff format, where even the lowest ranking team in league play can still win the Championship! League Champions are recognized on our brand new Trophy and receive T-shirts. Team picture is emailed to the team captain if requested and goes on our Wall of Champions. The Top Goal Scorer, Top Playmaker, and Top Goalie of each division receive a custom made prize with their individual stats listed for the session. Ties in regular season go to a 3 v. 3 three-minute-overtime, then sudden death shootout. Ties in playoffs go to sudden death overtime. 3 points for a reg- ulation win. 0 points for regulation loss. 2 points for OT/shootout win. 1 point for OT/shootout loss. The AAU Rulebook will be followed, but Epic Center’s house rules supersede some of them. For a complete list of league details, please see the back of this flier. *Please be aware that Start Week and End Week below may fluctuate as teams register. Session League League Regular Minimum Maximum League Register Number: Start Ending Season Total Total Fee: By: Week: Week: Games: Games: Games: Rink Rental Fees I 9/06/21 10/31/21 6 8 8 $700 8/23/21 Per Hour II 11/01/21 1/02/22 6 8 8 $700 10/18/21 Current Player*:$150 -

Summer 19 Elementary

CAMP FOOTHILLS 2019 Who? When? Why? • Week 1 5/28 - 5/31 • Grades K - 8th field trips only • Enjoy a 3 hour themed camp or Grades designation refers to the rotate from one experience to a 2018-2019 school year. • Week 2 6/3 - 6/7 totally different one each hour! • Week 3 6/10 - 6/14 What? • Flexible schedule. Attend morning, • Week 4 6/17 - 6/21 Sports, culture, STEM, art, drama, afternoon, or both! • • Week 5 6/24 - 6/28 cooking, etc. • Make it easy on yourself and pre- • Week 6 7/1 - 7/3, 7/5 • Classes that change weekly and field order lunch (M-F) Week 7 7/8 - 7/12 trips • • Pre-order or purchase homemade • Week 8 7/15 - 7/19 • Morning (9am -12pm) and Afternoon ice cream from Isabella’s on (1pm - 4pm) classes • Week 9 7/22 - 7/26 field trips only Wednesdays! 6th Grade Bootcamp 7/29 - 8/1 • Before and after class hours for • • Make new friends! grades K - 8th Where? • Catalina Foothills High School 4300 East Sunrise Drive SAVE TIME -Camp Foothills Round Trip with a click of a button! Save time and sign up for the ENTIRE summer us plan your child’s summer for you. Choose the round trip option and let all Field Trips will be included When you sign up for our Roundtrip Ticket, we can cater an experience around and we will send you a brief survey so scheduled for a class that isn’t your campers preferences.Was your camper up to five schedule changes their style? No problem! Campers will receive lunches, ice cream, and Camp on the house. -

Floor Hockey Playing Area

Special Olympics Canada Winter Sport Rules Floor Hockey ARTICLE XIII Floor Hockey The following Special Olympics Canada (SOC) sports rules shall govern all SOC floor hockey competitions. The Floor Hockey Rules have been broken into the following sections: Section A – Playing Area Section D – Officials Section B – Teams Section E – Rules of Play Section C – Equipment Section F - Infractions SECTION A Playing Area A-1- Playing Area Dimensions (as per rule 1) The rules within this section pertain to the playing area and the floor markings. I. The playing surface shall be a maximum of 17m x 31.6m (56’ x 103.7’) and a minimum of 12m x 24m (40’ x 80’) on a level surface and properly marked for Floor Hockey. The standard size shall be 14.6m x 26.8m (48’ x 88’). Diagram 1: October 2012 1 Special Olympics Canada Winter Sport Rules Floor Hockey II. The playing area may be defined by lines or boundary boards. Boundary boards must be constructed of quality sturdy material and 1.1m – 1.2m (42” – 48”) in height. If boundary boards of this dimension are not available no boards less than these requirements shall be used. Appropriate marking tape may be used in place of boundary boards. III. The playing area will be free from any unguarded projections which a player could encounter in the normal course of play. A-2 - Division of Playing Surface I. A 5 cm (2 in.) wide line shall be marked and extend between the two front goal posts. This line shall be known as the "Goal Line". -

Floor Hockey Study Guide

Floor Hockey Study Guide History Tom Harter, director of Civic Recreation in Battle Creek, Michigan, introduced the new game of floor hockey modified from the original game of ice hockey. Ice hockey began in Canada in the mid 1800’s. By 1900, it became the national sport of Canada. Since then, it has become more popular in many other countries, especially Russia, Sweden, and the United States. It is a fast paced game, and the only game allowing player substitutions during play. Now, over 1000 amateur players take part at the community, high school and college levels. Typically, hockey games are divided into 3-20 minute periods with 2 intermissions between them. The object is to score points by hitting the puck into the goal or net. Floor hockey is a modification of ice hockey with differences in rules and modifications and of course, no use of ice or skates. Balls can be used in replacement for pucks. Use of a ball makes stick handling easier and increases the pace of the game. Terms Assist ––– a pass from a teammate that leads to a goal. Blade ––– the curved end of the stick, front and back, used to hit the puck. Body or Shaft – the main part of the stick, used to hold and stickhandle. Butt or End – the end knob used for better grip, to keep the hand from sliding off the stick. Centering the puck ––– to pass to a spot (the point) in front of the opponents goal. Goalie Crease – the area where no player’s feet or stick, except for the goalie, is allowed during play. -

VSS/Raiffeisen Behindertensport in Südtirol Impressum Herausgeber: Verband Der Sportvereine Südtirols (VSS), Referat Behindertensport Brennerstraße 9, 39100 Bozen Tel

VSS/Raiffeisen Behindertensport in Südtirol Impressum Herausgeber: Verband der Sportvereine Südtirols (VSS), Referat Behindertensport Brennerstraße 9, 39100 Bozen Tel. +39 0471 974 378, Fax +39 0471 979 373 www.vss.bz.it, [email protected] Erscheinungsdatum: Februar 2017 2 Sportmöglichkeiten für Menschen mit Beeinträchtigungen in Südtirol 3 Liebe Freunde des Behindertensports! Seit zehn Jahren unterstützen die Südtiroler Raiffeisenkassen den VSS als Gene- ralsponsor. Ende vorigen Jahres wurde diese erfolgreiche Zusammenarbeit um weitere fünf Jahre verlängert. Eine von Vertrauen, Verlässlichkeit und Wertschät- zung geprägte Zusammenarbeit wird damit fortgesetzt. Darüber freue ich mich, denn die Förderung des Jugend- und Breitensports, wie sie der VSS in Südtirol betreibt, ist den Raiffeisenkassen seit Jahrzehnten ein besonderes Anliegen. Ob Fußball oder Leichtathletik, Behinderten- oder Seniorensport, Tennis oder Rad- sport – und andere Bereiche mehr: Sportförderung bedeutet immer eine Inves- tition in die Zukunft, und daher ist sie wertvoll! „Sport ist wert(e)voll“ – so lautet auch das heurige Jahresmotto des VSS. Und dass Sport wert(e)voll ist, kann ich als leidenschaftlicher Skifahrer, der auch gerne mal ein Skirennen fährt, nur voll bestätigen. Winston Churchill, der bekannte britische Staatsmann, brachte es so auf den Punkt: „Keine Stunde im Leben, die man im Sport verbringt, ist verloren.“ In diesem Sinne freue ich mich, dass der VSS auch Menschen mit Beeinträchti- gung ein breites Sportangebot eröffnet. Mit der Neuauflage dieser Broschüre werden die vielfältigen Möglichkeiten sportlicher Betätigung und auch das große Engagement der Vereine im VSS für den Behindertensport aufgezeigt. Ein Engagement, das Anerkennung verdient! Herbert Von Leon Obmann des Raiffeisenverbandes 4 Liebe Freunde des Behindertensports! Seit 1981, dem Internationalen Jahr für Menschen mit Behinderung, gibt es beim Verband der Sportvereine Südtirols (VSS) das Referat Behindertensport. -

Special Olympics MA Modified Floor Hockey Rules

FLOOR HOCKEY RULES AND MODIFICATIONS I. Equipment 1) The puck is a circular felt disc with a center hole. 2) Sticks other than goalkeepers' sticks must be a rod or dowel made of wood and/or fiberglass conforming to the following dimensions: a. The non-handle end (i.e. the bottom or floor end) of all sticks other than goalkeepers' sticks must be rounded-off. The stick must be of a uniform thickness over the entire length. No tape, string, or other object is allowed that will increase the diameter on the bottom of the stick. 3) The goalkeeper's stick shall be a regulation ice hockey goalkeeper's stick.. 4) Protective Equipment: The goalkeeper must wear a helmet with a facemask and protective gloves. The goaltender will be allowed to wear regulation sized ice hockey goalie pads and gloves or some reasonable facsimile thereof (i.e. street hockey pads, cricket pads, baseball glove ). The leg guards worn by goalkeepers must not exceed 31cm (12”) in extreme width when on the leg of the player. All other players are required to wear helmets with facemasks or shields that cover the entire face and shin guards to ensure safety. Proper athletic footwear such as running shoes must be worn by all persons on the playing surface during play. Black soled shoes are discouraged since they will mark the playing surface. Protective gloves and elbow pads are recommended. 5) Player Safety & Equipment It is the responsibility of Special Olympics to look out for safe and well-being of all of our participants and to manage any and all potential risks, which may result or cause an injury a participant. -

Bid Tabulation BSN Sports, Passon's Sports, Aluminum Athletic Aluminum Athletic School Speciality Inc

DATE: 4/2/2015 Purchasing Department 125 N. Division St. # B-3 BID - Sports & Craft Equipment Salisbury, MD 21801 Phone: 410-548-4805 Fax: 410-334-3130 Bid Tabulation BSN Sports, Passon's Sports, Aluminum Athletic Aluminum Athletic School Speciality Inc. S&S Worldwide and US Games Equipment Co. - Bid 2 Equipment Co - Bid 1 Outdoor Soccer Ball Size 3 $877.50 No Bid $1500.00* No Bid No Bid Outdoor Soccer Ball Size 4 $172.50 No Bid $330.00* No Bid No Bid Outdoor Soccer Ball Size 5 $294.00 $839.50 $560.00* No Bid No Bid Futsal Ball $72.00 $136.90 No Bid No Bid No Bid Indoor Soccer Ball $185.88 No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid Futsal Soccer Goals $1,848.96 $2,800.00 No Bid No Bid No Bid Softballs 11", .47 cor $335.64 No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid Softballs 12", .47 cor $335.88 No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid Softballs 11", .44 cor No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid Softballs 12", .44 cor No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid Indoor Softballs 11" $41.64 No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid Indoor Softballs 12" $53.88 $51.12 $63.60 No Bid No Bid Tee-Ball Bat 24"-28" $99.92* No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid Fast-Pitch Softball Bat 29"-30" $199.84* No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid Fast-Pitch Softball Bat 30"-32" $359.84* No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid Fast-Pitch Softball Bat 32"-34" $359.84* No Bid No Bid No Bid No Bid Volleyballs Indoor $132.60 $249.30 $320.00 No Bid No Bid Gater Skin Dodge Balls 8" $236.40* No Bid $288.00 No Bid No Bid Gator Skin Dodge Balls 6 1/4" $117.60* No Bid $223.20 No Bid No Bid Playground balls 8.5" $51.80 $86.20 $62.00 No Bid No Bid Red Playground Balls 10" dia $63.60 $43.00 $83.00 No Bid No Bid Basketballs UA $55.44 No Bid $60.00 No Bid No Bid Basketballs Li'l Champ 22" $31.80 No Bid $31.50* No Bid No Bid Football Synthetic, Jr. -

Spring/Summer 2018

MONOCACY DAY • MINI MONOCACY • MONOCACY ADVENTURE • MONOCACY SPORTS & GAMES ECO-ADVENTURE • NATURE • HISTORY • JUNIOR LIFEGUARDING • ARCHERY 20,000 LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA • A FAIRYTALE ADVENTURE IN ART • ABRAKADOODLE ART ADVENTURES IN COLOR • ALL BALL • HARRY POTTER • LEGO/MINECRAFT • SUPER HEROS ART BALL DIAMOND DYNAMICS • MONOCACY BASKETBALL. DEVELOPMENT FIVE-STAR BASKETBALLBEST BATON • CHEER & POMS • CHEERLEADING • SILVER KNIGHTS CHESS CHILDREN’S CHORUS • KIDS COOKING • MASTER CHEF • DESCEND INTO DANCE • EMERGE PLIESSUMMER AND PRINCESSES • POINT DISCOVERY • FENCING • FIELD HOCKEY. NFL FLAG FOOTBALL • GYMNASTICS • TUMBLING FOR CHEERLEADING FARM FUN DAYS • LACROSSE SCOOPERS • LITTLE STICKS LACROSSE • BREAKAWAY LACROSSE SURVIVAL AND STONEEVER AGE • 1ST KICKS SOCCER • LITTLE. HANDS COOKING MINI-SPORTS DISCOVERY • TINY SLUGGERS • QUIDDITCH • CLUB SCI AND KIDZART ELECTRONIC GAME DESIGN • JUNIOR ROBOTICS • GADGETS AND GIZMOS • SILVER KNIGHTS CODING SNAPOLOGY301.600.2936 • CHALLENGER | BRITISH RECREATER.COM SOCCER • FC FREDERICK | • UK ELITESPRING/SUMMER SOCCER • SOCCER 2018SOURCE 360 PEE WEE TENNIS • TENNIS INSTRUCTION • TENNIS AND SWIM • BEACH VOLLEYBALL • GO GET IT VOLLEYBALL Summer Camp Information CAMPER HEALTH FORM All camps that have an icon next to them (2) require a camper health information form to be filled out and brought to camp on the first day. All campers must have a completed health information form on file at the camp location in order to attend. You may receive additional forms/newsletter that are specific to your child’s camp through email before the camp begins. SIGNING IN/OUT Parent, guardian or authorized person over the age of 18 must sign campers in & out each day and must show photo identification. Staff are required to ID all persons picking up children. -

Loving Education at Home

Loving Education at Home Physical Education Program 2010–2011 Schedule About Us The Clark Sports Center facilities are Facilities include a gymnasium that located on Susquehanna Avenue, one features six basketball hoops and ample mile from the center of the village. Our space for gymnastics and gym floor organization offers a unique approach games, an indoor running track, eight to health and fitness in our community. lane bowling alley, swimming and diving While many aspects of The Clark Sports pools, fitness center, aerobics room, Center are duplicated in other facilities, squash and racquetball courts, the area’s we believe that no other single private only indoor and outdoor adventure recreational complex in the United States high ropes courses, an outdoor low brings together so broad a range of ropes challenge course, two indoor equipment, staff, and programming. rock climbing walls, four outdoor tennis Upon opening to the public in October, courts, sand volleyball court, numerous 1986, The Clark Sports Center has soccer and outdoor sports fields, and two established a reputation for quality softball/baseball fields. equipment, impressive design, and The Clark Sports Center staff are friendly innovative professional programming. and supportive career professionals with Everyone, from family groups to the most a variety of college degrees, certifications, serious athletes, will find The Clark Sports training, and experience. Center affordable and a pleasure to use. Program Information The Loving Education At Home (LEAH) All participants in the programs at program meets every Tuesday from 1:00 The Clark Sports Center are expected to 3:00pm beginning September 28, to behave in a safe and considerate 2010 until May 31, 2011. -

Our Mission Is to Provide Life-Changing Opportunities Through Sports and Physical Activity to Individuals Who Are Blind and Visu

.. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Our mission is to provide life-changing opportunities through sports and physical activity to individuals who are blind and visually impaired. Bell Basketball Audible bells inside allow individual to hear ball’s location Can be used for basketball or other ball games Also available, basketball with hand placement outlines (no bells inside) Foam Ball Beeper inside allows individuals to locate ball Can be used for a variety of recreational games Our mission is to provide life-changing opportunities through sports and physical activity to individuals who are blind or visually impaired. 1 Audible Football Audible football contains either beeper or bells to allow individual to hear ball’s location Can be used for football or other ball games Beeping foam football available Bell rubber football available Beeping Frisbee Beeper inside Frisbee allow individual to hear Frisbee’s location Soft design allows Frisbee to be used with all ages Beeper contained in Velcro pouch making it easy to switch on and off Can be used for recreational Frisbee, ultimate Frisbee, other games, or as a soft sound source Our mission is to provide life-changing opportunities through sports and physical activity to individuals who are blind or visually impaired. 2 Beep Kickball Sturdy construction allows for extended use Beeper inside allows individuals to locate ball Can be used for beep kickball or other recreational games High contrast yellow tape indicates beeper’s location High Contrast Golf Balls High contrast yellow color increases visual accessibility Come in packs of two Can be used for golf or other outdoor ball games Standard golf ball size and weight Our mission is to provide life-changing opportunities through sports and physical activity to individuals who are blind or visually impaired. -

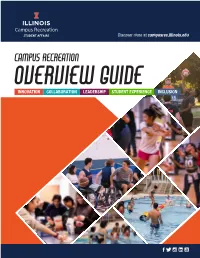

Campus Recreation Overview Guide INNOVATION COLLABORATION LEADERSHIP STUDENT EXPERIENCE INCLUSION

Discover more at campusrec.illinois.edu Campus Recreation Overview Guide INNOVATION COLLABORATION LEADERSHIP STUDENT EXPERIENCE INCLUSION Welcome to Campus Recreation Campus Recreation provides a welcoming environment for of state-of-the-art indoor recreation space available to everyone with sustainable facilities and programs that inspire concentrate on wellness and healthy lifestyles. Additionally, the university community to engage in recreation and 75 acres of outdoor fields between the Complex Playfields, wellness opportunities. the Outdoor Center Playfields, and the Illini Grove offer many opportunities for the students to stay active. Over 1,350,000 visits by patron each year. Students, faculty, staff, community members, and visitors use the facilities for Campus Recreation also offers many diverse programs and everything from education to cheering on friends to personal amenities, including over 50 group fitness classes each week, relaxation and meditation. a variety of intramural sports each semester, instructional cooking classes, wellness programs, rock climbing, learn-to-swim With the Activities and Recreation Center (ARC), Campus program, personal training sessions, bicycle demonstrations, Recreation Center East (CRCE), Campus Bike Center, and ice skating and hockey programs, and more than 40 club sports. the Ice Arena, there are approximately 500,000 square feet Vision: A Place for Everyone Values: INNOVATION COLLABORATION LEADERSHIP STUDENT EXPERIENCE INCLUSION Mission: Campus Recreation provides a welcoming environment -

Winter Spring 2018 - 19

Winter Spring 2018 - 19 Guide s of D ar ou Ye g la 0 s 0 s 2 1818 2018 C . Y IT . Lovely A. Warren, Mayor Y N O R, F E Rochester City Council ROCHEST R-Center Locations & Amenities Playground Gym Computer Lab Did you know? You can rent our facilities for Outdoor Courts Game Room Meals private use—parties, birthdays, reunions and more! Find a Indoor Pool Teen Lounge Community spot that’s perfect for you. Meeting Space Outdoor Pool Fitness Center Danforth Community Center Performance Space 200 West Ave. Spray Park After-school Satellite $395, 9 a.m. – 9 p.m., four-hour * increments, 150 people max. Adams Street Edgerton Stardust Ballroom Address: 85 Adams St. Phone: 428-7266 Hours: M-F, 2:30 - 9:30 p.m. | Sat 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. 41 Backus St. $445, 9 a.m. – 9 p.m., four-hour Flint Street increments, 240 max dinner style, Address: 271 Flint St. Phone: 428-7001 Hours: M-F, 2:30 - 9:30 p.m. | Sat 10 a.m. - 5 p.m. 400 max. theater style seating. Roxie Ann Sinkler Genesee Valley Field House 1316 Genesee St. Extension, Address: 75 Grover St. Phone: 428-7827 Hours: M-F, 2:30 - 9:30 p.m. | Closed Sat. Genesee Valley Park $195 per day, 10 a.m. – 9 p.m., four- Humboldt hour increments, 48 people max. Address: 1045 Atlantic Ave. Phone: 428-7294 Hours: M-F, 2:30 - 9:30 p.m. | Closed Sat. Lake Riley Lodge Frederick Douglass 100 Norris Dr., Cobbs Hill $470 per day.