Urban Design Review - Assessment Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Minutes of the Meeting Held on Thursday 19Th September 2019 at 11.45Am at Foakes Hall, Great Dunmow, Essex

Essex Association of Local Councils THE 75th ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Minutes of the Meeting held on Thursday 19th September 2019 at 11.45am At Foakes Hall, Great Dunmow, Essex The President Cllr John Jowers With the Executive Members and EALC Staff Margaret Grimster Vice President Cllr J Devlin Basildon Cllr D McPherson-Davis Basildon Cllr P Davey (Chairman) Brentwood Cllr R North Brentwood Cllr A Acott Castlepoint Cllr S Berlyn Chelmsford Cllr M Hessing Chelmsford Cllr S Jackman Epping Forest Mrs K Richmond Epping Forest Cllr R Martin Rochford Cllr M Cohen Rochford Cllr A Hafiz Maldon Cllr J Anderson Maldon Cllr M Talbot Tendring Cllr A Townsend Uttlesford Mrs H Symmons Southend Ms K O’Callaghan ECC Essex Association of Local Councils Staff Present Executive RFO & Joy Darby Chief Executive Officer Charlene Slade Buildings Manager Executive County Training Pearl Willcox Officer Louise Gambardella Funding Officer Rebecca Sheppard Office & Training Coordinator Amanda Brown Parish Support Officer Office & Training Danielle Frost Health & Wellbeing Officer Kerry Wood Administrator Tracy Millard Catering Summary of Delegates attending 99 delegates from 3 delegates from 11 Delegates from 5 Speakers Members representing Partner Organisations Other organisations 79 Member Councils 2 County Broadband David Jackman Mayor Bob Masey and Mayor Colin Riley staff Photography Deputy Janette Potter Castlepoint Borough (IT/Coms support) Chelmsford City Council Council Kirsty O’Callaghan Jonathan Owen Nick Shuttleworth ECC NALC RCCE In the Chair: The President 1. Welcome The President welcomed all District, Borough and City Councils and all Member Councils for attending the 75th Annual General Meeting of the Essex Association of Local Councils. -

Welcome to St Martin of Tours Basildon

Welcome to St Martin of Tours Basildon Parish Profile 2019 www.stmartinsbasildon.co.uk Contents 1. Basildon and Our Church at Present 3. What are we looking for in a new Priest? 5. What can we offer? 8. The Wider Context 9. Finance 10. The Rectory 11. Basildon 12. Conclusion Basildon and Our Church at Present Basildon is situated in South Essex, positioned between the A13 and the A127. It was one of the many New Towns that were developed following the New Towns Act of 1946. London, which had been badly damaged throughout the Second World War, was overcrowded and housing was largely very poor. ‘New Towns’ were the Labour Governments answer to the problem. This year we celebrate the 70th anniversary of the start of the work in the building of Basildon. St Martins stands in the centre of the town, adjacent to St Martins Bell Tower, built in the millennium, the first steel and glass Bell Tower in the world, and the Civic Centre, housing the secular aspect of Basildon. From the outside the building is not particularly impressive but step through the door and stand at the back, looking towards the altar, and the magnificence of this house of God really hits you. On the far east wall hangs a very large cross and when the lights are on, the shadow from the cross depicts three crosses on the wall; just as they stood together at Calvary, at the crucifixion. The Sanctuary, chancel steps and centre aisle are carpeted. But what now really strikes the on-lookers’ eyes are the breath-taking modern stained-glass windows on the south and north sides of the church, almost ceiling to floor. -

Acknowledgement Letter to Source

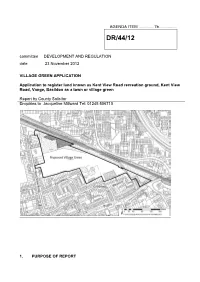

AGENDA ITEM ..............7b................ DR/44/12 committee DEVELOPMENT AND REGULATION date 23 November 2012 VILLAGE GREEN APPLICATION Application to register land known as Kent View Road recreation ground, Kent View Road, Vange, Basildon as a town or village green Report by County Solicitor Enquiries to Jacqueline Millward Tel: 01245 506710 1. PURPOSE OF REPORT To consider an application made on by Mr N E Hart of 88 Kent View Road, Vange, Basildon under Section 15 of the Commons Act 2006 (“the 2006 Act”) , to register land at Kent View Road Recreation Ground, Vange as a town or village green. 2. BACKGROUND TO THE APPLICATION The County Council has a duty to maintain the Registers of Commons and Town and Village Greens. Under Section 15 of the 2006 Act applications can be made to the Registration Authority to amend the Register to add new town or village greens. The County Council as Registration Authority has received an application made by local resident Mr Hart to register the application site as a Town or Village Green under the provisions of Section 15(2) of the 2006 Act. The twenty year period for the application is 1990 to 2010. The application was advertised in the local press and on site. Notice was also served on landowners. The County Council received objections to the application from the landowner, Basildon Borough Council. Prior to the advertisement the landowner had made representations that it had ‘appropriated’ the land from open space so that it could obtain planning permission and dispose of the land. The appropriation took place on 19 July 2010 for planning purposes under section 122(2A) Local Government Act 1972, including the prescribed publicity in the local press, in response to which no objections were received. -

Basildon PS Celebrates Its Golden Jubilee

BPS Golden Jubilee Spring StampEssex 2018 STAMP FAIR & EXHIBITION Saturday 28 April 2018 James Hornsby High School Leinster Road, Laindon, Essex, SS15 5NX 10.00—16.00 Welcome Brochure organised by on behalf of BASILDON PHILATELIC SOCIETY ASSOCIATION OF ESSEX PHILATELIC www.basildon-philatelic.org.uk SOCIETIES www.stampessex.org.uk Welcome from the Basildon President: Thank you very much for coming today to Basildon society’s Golden Jubilee event. We are very proud to have served the collectors of Basildon and the surrounding district for fifty years. We hope that we will be able to do so for many years to come. It is easy to sit at home and collect in splendid isolation, but why would anyone want to do so? There is so much pleasure to be gained from exchanging news and information with fellow collectors in a friendly environment, watching visiting displays, bidding in Auctions, displaying one’s own collection, etc., with access to the expertise of fellow members and the reference books from our extensive library. We meet at George Hurd Centre, just off Broadmayne, usually on the first Monday and third Tuesday of the month, at 7.30pm for 7.45pm. Why not come along? Welcome from the AEPS President: Thank you for joining us today to celebrate Basildon society’s Golden achievement. Basildon has always played a major role in the county association and currently provides three of the AEPS’s executive committee. I would like to thank all those, from Basildon and other societies, who have taken a role in organising and promoting today’s celebration and wish Basildon a strong and prosperous future. -

Pick of the Churches

Pick of the Churches The East of England is famous for its superb collection of churches. They are one of the nation's great treasures. Introduction There are hundreds of churches in the region. Every village has one, some villages have two, and sometimes a lonely church in a field is the only indication that a village existed there at all. Many of these churches have foundations going right back to the dawn of Christianity, during the four centuries of Roman occupation from AD43. Each would claim to be the best - and indeed, all have one or many splendid and redeeming features, from ornate gilt encrusted screens to an ancient font. The history of England is accurately reflected in our churches - if only as a tantalising glimpse of the really creative years between the 1100's to the 1400's. From these years, come the four great features which are particularly associated with the region. - Round Towers - unique and distinctive, they evolved in the 11th C. due to the lack and supply of large local building stone. - Hammerbeam Roofs - wide, brave and ornate, and sometimes strewn with angels. Just lay on the floor and look up! - Flint Flushwork - beautiful patterns made by splitting flints to expose a hard, shiny surface, and then setting them in the wall. Often it is used to decorate towers, porches and parapets. - Seven Sacrament Fonts - ancient and splendid, with each panel illustrating in turn Baptism, Confirmation, Mass, Penance, Extreme Unction, Ordination and Matrimony. Bedfordshire Ampthill - tomb of Richard Nicholls (first governor of Long Island USA), including cannonball which killed him. -

Great Burstead Conservation Area Character Appraisal

WWW.BASILDON.GOV.UK GREAT BURSTEAD CONSERVATION AREA CHARACTER APPRAISAL November 2011 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Planning Policy Context 3 Location and Setting 5 History and Archaeology 7 Spatial Analysis 12 Character 17 Summary of Issues 22 Townscape Appraisal Map 23 References 25 Appendix Listed Buildings 27 Contacts 29 Great Burstead Conservation Area – Character Appraisal 76 77 Not to Scale 81 81a 83 83a 88 43.0m 85 BM 43.84m 100 97 110 onds CHURCH STREET 48.8m 109 120 53.6m 124 111 Vicarage 128 Drain 130 LB 125 St Mary Magdalane Church Hall BM 53.9m 55.45m Pump House 129 Pond 143 Cemetery 55.2m TREET 179 Path (um) 137 135 N 143 This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of on behalf Controller Her Majesty’s Stationery Office © Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. (10018871) (2010). Conservation Area Boundary with Listed Buildings shown hatched Great Burstead Conservation Area – Character Appraisal INTRODUCTION Great Burstead Conservation Area Great Burstead Conservation Area was first designated in April 1983 and its boundaries have not been reviewed since. It comprises a small area centred on the Church of St. Mary Magdalene, near the western edge of the village and encompasses the historic part of the village on either side of Church Street on the approach to the densely built up section to the east, mainly consisting of late 20th century housing. It is centred on the Church, of Norman origin, and the three listed buildings which date from the 16th and 17th centuries. -

The Essex Birdwatching Society Newsletter the Natural Home of Bird Recording and Birdwatching in Essex Since 1949 October 2020 Issue 45

The Essex Birdwatching Society Newsletter The Natural Home of Bird Recording and Birdwatching in Essex since 1949 October 2020 Issue 45 Dear Essex Birders With chillier mornings and cooler days, we are very much in autumn now and many of our summer migrants will be replaced by autumn and winter migrants in the coming weeks. We were hoping to launch the Big County Birdwatch around now but with recent Covid restrictions we have had to adapt this years effort so we will now have THE BIG COUNTY GARDEN BIRDWATCH running from Friday 2nd - Monday 5th October 2020. I hope to send details of this great event in the next week or so.... watch this space! Best wishes to all. Steve IMPORTANT INFORMATION Due to the new law which came into force on Monday 14th Sept 2020 regarding the number of people (Maximum of 6) that are legally permitted to meet in a social gathering, it is with regret that all EBwS field trips planned for 2020 have had to be cancelled. Short-eared Owl by Steve Grimwade Registered Charity No. 1142734 www.ebws.org.uk Essex Ornithological Summary August 2020 by Howard Vaughan RSPB Rainham Marshes August was fairly slow going with few passage waders using the reserve as it was still very dry till later in the month. However, there were Green and Common Sandpipers to see and a Wood Sandpiper showed well on the 15th. Down on the river there were still Avocets and a few Black-tailed Godwits and a single Bar-tailed on the 1st. The immature Spoonbill was seen all month and a Cattle Egret arrived on the 7th and briefly became five on the 19th. -

South Essex Outline Water Cycle Study Technical Report

South Essex Outline Water Cycle Study Technical Report Final September 2011 Prepared for South Essex: Outline Water Cycle Study Revision Schedule South Essex Water Cycle Study September 2011 Rev Date Details Prepared by Reviewed by Approved by 01 April 2011 D132233: S. Clare Postlethwaite Carl Pelling Carl Pelling Essex Outline Senior Consultant Principal Consultant Principal Consultant WCS – First Draft_v1 02 August 2011 Final Draft Clare Postlethwaite Rob Sweet Carl Pelling Senior Consultant Senior Consultant Principal Consultant 03 September Final Clare Postlethwaite Rob Sweet Jon Robinson 2011 Senior Consultant Senior Consultant Technical Director URS/Scott Wilson Scott House Alençon Link Basingstoke RG21 7PP Tel 01256 310200 Fax 01256 310201 www.urs-scottwilson.com South Essex Water Cycle Study Limitations URS Scott Wilson Ltd (“URS Scott Wilson”) has prepared this Report for the sole use of Basildon Borough Council, Castle Point Borough Council and Rochford District Council (“Client”) in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed. No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by URS Scott Wilson. This Report is confidential and may not be disclosed by the Client or relied upon by any other party without the prior and express written agreement of URS Scott Wilson. The conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others and upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has been requested and that such information is accurate. Information obtained by URS Scott Wilson has not been independently verified by URS Scott Wilson, unless otherwise stated in the Report. -

Family Tree Maker

Descendants of WILLIAM MARTIN WILLIAM Ann MARTIN Baylis 1801 - 1800 - 1869 Born: Abt. 1801 Born: Abt. 1800 in Ramsden Crays Married: 04 Dec 1822 in Buttsbury Died: 09 Sep 1869 in Union Workhouse, Billericay Caroline Sarah Maria George Elizabeth WILLIAM Susanne Sarah James James John Eliza Martin Devenish Martin Britton MARTIN Elvin Martin Martin MARTIN Atkins 1822 - 1817 - 1871 1824 - 1830 - 1826 - 1872 1831 - 1829 - 1830 - 1835 - 1912 1837 - 1918 Born: 18 Nov 1822 in Born: Abt. 1817 in Great Born: 07 May 1824 in Born: Abt. 1830 in Stock Born: 21 Mar 1826 in Born: 1831 in Billericay Born: 14 Jan 1829 in Born: 20 Jul 1830 in Born: 15 Mar 1835 in Born: Abt. 1837 in Billericay Waltham, Essex Great Burstead Married: 04 Oct 1879 Great Burstead Married: 27 Oct 1850 Great Burstead Great Burstead Great Burstead Basildon Married: 13 Aug 1843 in Ramsden Crays Died: 19 Jul 1872 in in BUTTSBURY Died: 25 Mar 1912 in Married: 05 Dec 1852 in Great Burstead Union Workhouse PARISH CHURCH Norsey Road, Billericay in Great Burstead Died: Abt. 1871 in Billericay Essex Died: 1918 Billericay George Benjamin James Ellen Harriet Louisa Nathan Joseph Sarah Eliza Sarah William William Louisa GEORGE EMMA RHODA Elizabeth Charles Annie Maria John Elizabeth Hannah Hannah Robert James Annie Alice Loui Ellen Emily Elizabeth William John Eliza Clara Mary A Alice Mabel Brown Unknown Unknown Martin Martin 1852 - Martin Martin Garland Martin Unknown Martin Martin Harvey Martin Speller MARTIN FLACK MARTIN Martin Drake MARTIN FLACK MARTIN MARTIN 1866 - MARTIN Martin Martin Martin Bright Martin Martin Martin Martin Martin Martin Married: 1899 Martin Martin 1843 - 1846 - 1899 Born: Abt. -

Mark Stevenson Report Chelmsford City Council Water Cycle Study

TDC/014 FINAL Tendring District Council Water Cycle Study Final Report Tendring District Council September 2017 Tendring District Council Water Cycle Study FINAL Quality information Prepared by Checked by Approved by Christina Bakopoulou Carl Pelling Sarah Kelly Assistant Flood Risk Consultant Associate Director Regional Director Christopher Gordon Senior Environmental Engineer Revision History Revision Revision date Details Authorized Name Position 0 24/08/2017 First Draft 24/08/2017 Sarah Kelly Regional Director 1 29/09/2017 Final Report 29/09/2017 Sarah Kelly Regional Director Prepared for: Tendring District Council Prepared by: AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited Midpoint Alencon Link Basingstoke Hampshire RG21 7PP UK T: +44(0)1256 310200 aecom.com September 2017 AECOM i Tendring District Council Water Cycle Study FINAL Limitations AECOM Infrastructure & Environment UK Limited (“AECOM”) has prepared this Report for the sole use of Tendring District Council (“Client”) in accordance with the Agreement under which our services were performed (“AECOM Tendring District WCS proposal with T&Cs”). No other warranty, expressed or implied, is made as to the professional advice included in this Report or any other services provided by AECOM. The conclusions and recommendations contained in this Report are based upon information provided by others and upon the assumption that all relevant information has been provided by those parties from whom it has been requested and that such information is accurate. Information obtained by AECOM has not been independently verified by AECOM, unless otherwise stated in the Report. The methodology adopted and the sources of information used by AECOM in providing its services are outlined in this Report. -

Coastal Typologies: Detailed Method and Outputs

Roger Tym & Partners t: 020 7831 2711 Fairfax House f: 020 7831 7653 15 Fulwood Place e: [email protected] London WC1V 6HU w: www.tymconsult.com Part of Peter Brett Associates LLP Marine Management Organisation Coastal typologies: detailed method and outputs Final Report July 2011 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................5 2 TYPOLOGY METHODOLOGY ..............................................................................................6 Are existing typologies appropriate? ......................................................................................6 The indicators used in the cluster analysis .............................................................................7 Short-list of indicators used in the typology ..........................................................................11 Variable standardisation .......................................................................................................13 Weighting indicators .............................................................................................................13 Creating the clusters ............................................................................................................13 Secondary cluster analysis ...................................................................................................15 Categories and names .........................................................................................................15 -

Basildon Town Centre Regeneration Early Engagement Results

Basildon Town Centre Regeneration Early engagement results Contact: Strategy, Insights and Partnerships team, [email protected] Release Date: 05/08/2021 CONTENTS 1. Survey context 1.1 Age representation 1.2 Location representation 2. General summary 3. Trend analysis 3.1 Visiting frequency 3.2 General design - activity elements 3.3 General design – aesthetic principles 3.4 Specific design – housing 3.5 Specific design principles – height criteria 3.6 Specific design – height estimates 4. Areas of further investigation 1. Survey context The consultation took place between 9 June and 7 July 2021. A total of 2948 people participated in the survey. The survey took on average 21 mins to complete. This sample size provides a confidence level of 95% with a confidence interval of + or - 1.79. 1.1 Age representation Respondents aged 16 to 24 present the highest under-representation gap; the most over- Middle-aged people are represented group was aged 60 to 64. over-represented in the survey sample The age bands were grouped into further categories for this analysis, based on life stages: - Starting out and young families – ages 16 to 39 (representing 30% of the sample) - Middle -aged – ages 40 to 59 (40% of respondents) - Close to or retired – people aged over 60 (30% of respondents) The biggest representation gap is for ages 16 to 24 The # of respondents who have not completed their age have been removed (210 out of a total of 2 948) 1.2 Location representation The survey responses had over-representation from the towns of Basildon and Laindon, with Billericay and Wickford being under-represented.