Paul K. Macdonald and the Surprising Success of Joseph M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scheduled Football G

Bicentennial celebrated with >- PACK IT IN Q FOR SUMMER cC Buy I", a= Get 2nd one 112 Buy 3", c:) Get I Free I ~ W IT) <[ Mix & Match Sale! N All your favorite skin care products and makeup discounted and can be combined, Stock up now ~ and save, With Elizaheth Grady products, beautiful. healthy skin couldn', be easier Order now and W beauty will be in tho bag, Call I-BOO-FACIALS or VIS it wv.rw.,ellizal,etlhgrad),.con! Bill Drury, senior master sergeant of the Air' ~~~':~J,GUard of Massachusetts, leads the United States for nearest location. serVICes, products & gift cert i fi(:a tf'~, anthem during a concert at Chandler Pond TI Aug. 9. Summer Time is a Great TIme to Com,eltl Convert To Clean Dependable Natural Gas Hel~.lrla G 1 A DISCOUNTED Scheduled ~ ..........·15httime ard BOILER' SPECIAL GAS CONVERSION "ul~/J~jl: ~ 'Cali (617) 964-9600 for delt~lI.o l i football g_ ..... e angers ..... .r1IoJsidents SerVing Newton For More Than 30 WE WilL BEAT OR MEET ANY By Richard Cherecwlch tbe ' however, if Harvard wants to different things, COMpETITOR'S PRICE ON WATER HEA,r~R'S . STAFF WRITER hold f,venls, we have to go to the "FOOtbaU~ters to undergrads and drinking Free Appointment 0 Free Home Survey. Free F~llirrl.t" Harvard University will go before the city's entertamment license commission to get ap before. It's a completely different atmos Water Heater Replac!;l ment 0 Same Day SPlv;",ol licensing and entertainment board on Aug, 20 proval We will also let the neighborhood phere," she 'd, "Anyone around for footbaU to get approval for its 2007 football schedule, know we ever intend to do something like games kno s they have tremendous impact which includes a nighttime ganle that several on the co unity," residents said rescinds on a previous promise Ie force said that the community was Task fo member John Bruno mentioned ~ ~ , ~o ~ !,~,, ~o ~ ol. -

Tom Lanoye (Virtueel), Dj Vadim, Ramsey Nasr

De Standaard ANTWERPEN 100.9 - BRABANT 100.6 - GENT 94.5 - LEUVEN 88.0 (*. LIMBURG 101.4 - OOST & WESTVLAANDEREN 102.1 - en via DAB - stubru.be "poets who read their work in public may have other bad habits" Mark Twain DE NACHTEN 2004 EDiTiE» Niks geen metaforen over metrostations, luchtmachtbasissen of weerhutten die u De Nachten overzichtelijk helpen maken. Lang leve het onontwarbare raster, de helgroene matrix, het gesuis van elektronen in het spinrag van de dag. Zoek geen lijnen! Alleen knopen, waarin literatuur en muziek naar goede gewoonte snijden met performance, film en beeldende kunst. 6 podia, x schrijvers, y muzikanten, grote namen naast onbekend talent, meer dark- rooms, nog nauwer, nog grauwer. Divers en dwingend getrompetter. De Nachten is De Nachten. Het Armageddon van hedendaagse kunst. Klaar. IfRiJOAO FLIP KOWLIER, ALEX CHILTON + PAWLOWSKI + DEWEZE + DE BACKER, ABDELKADER BENALI, SANDY DILLON, SOUTH SAN GABRIEL. BART MOEYAERT, TOM LANOYE (VIRTUEEL), DJ VADIM, RAMSEY NASR ,... ZATERDAG TWINEMEN (EX MORPHINE), LARS HORNTVETH (JAGA JAZZIST) + STRIJKOCTET, DWARSKIJKER, MAURO & THE GROOMS, PASCALE PLATEL, "studio, MINTZKOV LUNA + GUESTS, BACH BUKOWSKI, STYROFOAM,... brussB Life is muf c Cl ViUA BELGiCA... jaar in primeur of in première te zien, vandaag met medailles overladen: ABDELKADER BEN ALI won de Libris Literatuurprijs, Carolina Trujilo Piriz de Nederlandse debuut ...is 1 van de motto's van 9 jaar De Nachten, vandaar een constante en prominente prijs, Tom Lanoye De Gouden Uil Literatuurprijs, Tonnus Oosterhoff de VSB-Poëzie- aanwezigheid van ons vaderlands muziektalent op de verschillende podia. En dit prijs en Margot Vanderstraeten de Vlaamse debuutprijs. Dat allemaal in 2003 en dat zonder verplicht quotum! MAURO is de recordhouder met 7 dienstjaren. -

2009–2010 Season Sponsors

2009–2010 Season Sponsors The City of Cerritos gratefully thanks our 2009–2010 Season Sponsors for their generous support of the Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts. YOUR FAVORITE ENTERTAINERS, YOUR FAVORITE THEATER If your company would like to become a Cerritos Center for the Performing Arts sponsor, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. THE CERRITOS CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (CCPA) thanks the following CCPA Associates who have contributed to the CCPA’s Endowment Fund. The Endowment Fund was established in 1994 under the visionary leadership of the Cerritos City Council to ensure that the CCPA would remain a welcoming, accessible, and affordable venue in which patrons can experience the joy of entertainment and cultural enrichment. For more information about the Endowment Fund or to make a contribution, please contact the CCPA Administrative Offices at (562) 916-8510. Benefactor Audrey and Rick Rodriguez Yvonne Cattell Renee Fallaha $50,001-$100,000 Marilynn and Art Segal Rodolfo Chacon Heather M. Ferber José Iturbi Foundation Kirsten and Craig M. Springer, Joann and George Chambers Steven Fischer Ph.D. Rodolfo Chavez The Fish Company Masaye Stafford Patron Liming Chen Elizabeth and Terry Fiskin Charles Wong $20,001-$50,000 Wanda Chen Louise Fleming and Tak Fujisaki Bryan A. Stirrat & Associates Margie and Ned Cherry Jesus Fojo The Capital Group Companies Friend Drs. Frances and Philip Chinn Anne Forman Charitable Foundation $1-$1,000 Patricia Christie Dr. Susan Fox and Frank Frimodig Richard Christy National Endowment for the Arts Maureen Ahler Sharon Frank Crista Qi and Vincent Chung Eleanor and David St. -

The Following Issue Is Misnumbered and Dated. It Should Have

The following issue is misnumbered and dated. It should have appeared as Vol. 16, No. 9, Feb. 6, 1995. Sn71 TV/ XKT-. 1i r'~r TnTTLrnroV l-CiT Patirep'nrnrirMllnltv' r raer reuruaivJ u, p On The Inside E~t A F3~rW?~fP~i~iP S ~E~Cm~ · P~ a---~-~·--aa~onrs*;·i 77 !/17 Ile to 777:,-sa~aer wo a. pa~j~g by Robert V. Gilheany station to station because of the attention he paid to because he felt that Mumia was too gifted a speaker and MOVE. The police attacked MOVE in 1978. 15 it was unfair to the prosecution. He also denied him his Support is growing to free Mumia Abu-Jamal, a political MOVE members were convicted of killing one cop, right to the council of his choice, which was MOVE prisoner On death row in Pennsylvania. A defense to save who was actually killed by another cop in a case of leader John Africa, Sabo saddled Mumia with an inex- his life is being fought. Moves to get him a new trial is "friendly fire." In case of police brutality the victim perienced unprepared counsel, who was latter disbarred underway and on Saturday February 11 a rally will be held gets charged with assault. Mumia followed the story and from practicing law. Mumia protested during the trial at PS. 41 116 W. street 11th (at 6th ave) in Manhattan. interviewed MOVE in prison. This lead to a public and was banished from the court room. Mumia spent Who is Mumia Abu-Jamal, he is a black radical advo- threat from then Mayor Frank Rizzo aimed at Mumia most of his trial in a jail cell. -

Pitchfork Mental Health

“NAME ONE GENIUS THAT AIN’T CRAZY”- MISCONCEPTIONS OF MUSICIANS AND MENTAL HEALTH IN THE ONLINE STORIES OF PITCHFORK MAGAZINE _____________________________________________________________________________ A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri-Columbia ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________ By Jared McNett Dr Berkley Hudson, Thesis Supervisor December 2016 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled “NAME ONE GENIUS THAT AIN’T CRAZY”- MISCONCEPTIONS OF MUSICIANS AND MENTAL HEALTH IN THE ONLINE STORIES OF PITCHFORK MAGAZINE presented by Jared McNett, A candidate for the degree of masters of art and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Berkley Hudson Professor Cristina Mislan Professor Jamie Arndt Professor Andrea Heiss Acknowledgments It wouldn’t be possible to say thank enough to each and every person that has helped me with this along my way. I’m thankful for my parents, Donald and Jane McNett, who consistently pestered me by asking “How’s it coming with your thesis? Are you done yet?” I’m thankful for friends, such as: Adam Suarez, Phillip Sitter, Brandon Roney, Robert Gayden and Zach Folken, who would periodically ask me “What’s your thesis about again?” That was a question that would unintentionally put me back on track. In terms of staying on task my thesis committee (mentioned elsewhere) was nothing short of a godsend. It hasn’t been an easy two-and-a-half years going from basic ideas to a proposal to a thesis, but Drs. -

Arbiter, October 22 Students of Boise State University

Boise State University ScholarWorks Student Newspapers (UP 4.15) University Documents 10-22-1997 Arbiter, October 22 Students of Boise State University Although this file was scanned from the highest-quality microfilm held by Boise State University, it reveals the limitations of the source microfilm. It is possible to perform a text search of much of this material; however, there are sections where the source microfilm was too faint or unreadable to allow for text scanning. For assistance with this collection of student newspapers, please contact Special Collections and Archives at [email protected]. 'I 1 WEDNESDAt OaOBER22,1997 ---, •••• _----- -~_. __ ._--_ • .,-- •• _- --- .-._--'~'-- .. - •• ~_ - •• > WEDNESDAY, OaOBER 22, 1997 by Eric Ellis 6U'(S ::r:tJGeO@) 1b"fi.lINj(F~ A . WHIt6J So 1: nt.C(OG'O "'-0 ~AK€ A Ro,4D- TRll'S:X-rniW6St: 1 ( •••••••••••••••••••••.•••••••••••••••••.••••••• -".I!~~a.a.LIl.LL& .......-..JLLL&.LI~L&.LJ. educat.ion : I Top T~n reason's why Dirk 1 Kempthorne The { S({J)1UUrce should come for NEWS home and at become Idaho's BSU governor by Asencion Ramirez Opinion Editor 10. He's always·wanted to be the HSIC (Head Spud In Charge). 9. It's one way for the nation to stop associating him with Helen Chenoweth. (Hell,it's the reason voters sent her to Washington). 8. If he doesn't do it, Bruce Willis will. 7. "Kempthorne Kicks @$$" makes for a good slogan. 6. Spending four years in Boise seems a lot more fun than spending four more years in Washington with Larry Craig. 5. -

Continental Drift. Catie Curtis Is Not the Type to Home-Curtis, Backed by Conway Dolinist Jimmy Ryan, a Longtime Take an Opportunity for Granted

Artists & Music Catie Curtis Eyes Road Rebound With Ryko /Palm Debut Dar Williams, Late Morphine Singer Influence 'My Shirt Looks Good On You' BY SCOTT BROOKS called Rykodisc and Boston in Curtis' interaction with man- Continental Drift. Catie Curtis is not the type to home-Curtis, backed by Conway dolinist Jimmy Ryan, a longtime take an opportunity for granted. and Colley, pays tribute to the collaborator who, with Sandman, Fresh from recording her fourth singer with a cover of Sandman's formed the Pale Brothers. album, My Shirt Looks Good on According to Curtis, the inter- UNSIGNED ARTISTS AND REGIONAL NEWS You (RykodiscfPalm Pictures, Aug. play between her voice and 1EI Y I_ A R R Y F I_ I C K 21), the singer /songwriter is Ryan's electric mandolin is the about supporting the album focal point of this album and a excited Even though they all happen to be with a fall tour. feature that her listeners will PLOUGHING THROUGH: find distinctive. openly gay, the members of Ploughound are not inclined to be "This is one of those big bands "I mean, you "Everybody has heard electric grouped under the ever -expanding contingent of "queercore" moments," she says. underground. only have a few of them in your guitar since the dawn of time," currently making noise along the indie -rock San Francisco -based act is ever likely to f career. Every time a record comes Howard says. "To hear somebody In fact, the closest the is not all gay men worship out that's actually being supported, playing something slightly differ- get to making a political statement that ride the wave. -

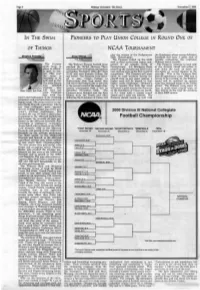

In the Swim Pioneers to Play Union College in Round One Of

PageS Widener University: The Dome November 17, 2000 IN THE SWIM PIONEERS TO PLAY UNION COLLEGE IN ROUND ONE OF OF THINGS NCAA ToURNAMENT play the winner of the Bridgewater the Dutchmen whose young defensive (MA) - Hobart game. ' / backfield will have a great deal of The Pioneers picked up the sixth trouble containing the explosive seed in their seven-team region com Widener aerial assault. The Pioneer The Widener Pioneer football team prised of all , schools north of The Pioneers continue to look only swim team is watched the NCAA Division Three Pennsylvania. 8-0 Brockport State at the obstacle ahead and refuse to about to official selection show with great anticipation picked up the number one seed in the look down the road, as there are ly open its sea on Sunday, November 12th after their east and has a bye in the first round of absolutely no second chances in the son. This year 37 -22 win over Juniata College the competition. The Pioneers will most playoffs. This is the Pioneers first the team is day before. The Pioneers were select likely be road warriors during the playoff appearance since 1995 and it expec'ting to do ed to play Union College in playoff stint as any game against a proves to be exciting, as the Widener well and go far. Schenectady, New York where they higher seed will be played at that squad will be matched up against The team return will travel on Friday to try to advance higher seed's institution. Widener's some less talented teams in the weeks may talented to the second round_of the single-elim trip to up~tate New York this week ahead. -

SLAMMIN' Rankings Released

An Associated Collegiate Press Pacemaker Award Winner TUESDAY March 7, 2000 • Volume 126 THE • Number 36 Review Online on-Profit Org. U.S. Postage Paid www. review. udel.edu ewark, DE Permit No. 26 250 Student Center • University of Delaware • Newark, DE 19716 FREE No smoking next year in on-campus housing BY STEPHANIE DENIS of smoking bans on airplanes. housing now, it should be m ore AdministrClfil·e News Editor Roselle stated in an e-mail than enough time to find a place to All university-owned housing message that he hopes th e new live," she said. will be smoke-free starting in the smoking policy will decrease the However, j unior Jessica Ribble, Bans reflect a Fall Semester, President David P. total number of stude nts who who lives off-campus, said students ' Roselle announced Friday. smoke. now do not have enough time to Roland M. Smith, vice president " On the other hand, the airlines find a decent place to live off for Student Life, said both health decided that making nonsmokers campus for the Fall Semester. ,national trend and safety issues were factors in the more comfortable was sufficient Linda Carey, director of Student BY LINA HASHEM university' s decision. reason to ban in-flight smoking." Housing Assignment Services. said Managing News Ediror s he is not anticipating many Cigarettes are the leading cause he said. University students who will be prohibited from of fires and fire fatalities, he said. " The decision is a logical housing cancellations because of smoking in their resi_dence halls next semester will be in and the da maging effects of outcome of increasing the number the new policy. -

Z Pacanowa Do Los Angeles | 1

Z Pacanowa do Los Angeles | 1 29 października 2018 Z Pacanowa do Los Angeles Karolina Kępczyk rozmawia z malarką Anną Osiecką. Pada. Zimno. Jesienna plucha w Pacanowie. Ja bez słońca nie działam, więc jadę na spotkanie z artystką po energię. Mieszka nad Wisłą. Pochodzi z Krakowa, jest absolwentką Akademii Sztuk Pięknych, od dwóch lat mieszka w Kępie Lubawskiej na terenie gminy Pacanów. Umawiałyśmy się od pół roku i wreszcie… W domu, a zarazem pracowni malarskiej jest ciepło. Od progu wita mnie przesympatyczna osóbka o śmiejących się oczach – Anna Osiecka. W porcelanowym imbryku parzy się herbata, na stole dziergany obrus, dynie, zasuszone kwiaty. W tle transowa muzyka. Jemy orkiszową domową szarlotkę i galaretkę z truskawkami z ogrodu artystki. Jest przytulnie jak u babci. Bo Pani Anna wyznaje zasadę rodzinną: Trzeba ugościć! I ta gospodyni od szarlotki i truskawek wkrótce ma wystawę w USA! Jak się to robi? Tekst pochodzi ze strony www.swietokrzyskie.pro Z Pacanowa do Los Angeles | 1 Z Pacanowa do Los Angeles | 2 – Czego słuchamy? – To grupa „Morphine”, trio z Cambridge (USA). Zaczęli w latach 90-tych. – To ważna dla Pani muzyka? Przypomina mi „Archive”, którego słucham i jeżdżę na koncerty. – Bardzo lubię, słucham malując. Słucham różnej muzyki: jazz, klasyczną, rock, industrial, pop z lat 80-tych, Morphine to trio łączące elementy stylistyki rocka z elementami bluesa i jazzu. Skład: Mark Sandman, założyciel, który już nie żyje, Dana Colley, Jerome Deupree, Billy Conway. – Artystka po ASP zostawia artystyczny Kraków, bohemę, dla małej wioski w Świętokrzyskim. To dość nietypowe. O co tu chodzi? – Lubię wieś. Inspiruje mnie twórczo. Uspokaja. -

Persrecensie : Interdisciplinariteit in Maten En Gewichten

Algemeen Interdisciplinariteit in maten en gewichten Tom Michielsen 02-02-2004 Pag. 20 vrijdag 30 en zaterdag 31 januaridesingel, antwerpen De Nachten 'Wij dolen weg zonder kompas': het zat verstopt in de virtuele videobrief, die Tom Lanoye had samengesteld met restanten van zijn monoloog 'Veldslag Voor Een Man Alleen'. Het herinnerde er de Nachten-gangers op gezette tijden aan dat ze niet alleen waren. Het was voorwaar een rustgevende gedachte in het gewriemel, want dat was het keer op keer als je het comfort van de pluche wilde omruilen voor een andere omgeving. Met twee grote zalen (blauwe en rode), drie middelgrote (foyer, trappenpodium en darkstage) en nog een dozijn kleinere ruimtes was het aanbod ruim genoeg om altijd iets te missen. Het enige houvast voor de bezoeker van het jaarlijkse interdisciplinaire cultuurfeest was het programmaboekje met een woordje uitleg en (richt)uren, maar helemaal zeker was hij nooit. Lanoye, zelf op schrijfvakantie in Zuid-Afrika, deed trouwens zijn voordeel met de beeldregie van de videokunstenaar Toon Van Ishoven. In een verduisterde zaal gaf zijn enscenering op doek toevallige passanten soms de indruk dat de schrijver zelf op het podium stond. Het maakte hem meer aanwezig dan sommige dichters in de blauwe zaal, die niet eens de spot op zich gericht kregen. Waarom het hele podium verlicht bleef tijdens de solovoordrachten van onder meer de debutante Annelies Verbeke, Yves Petry en Bart Moeyaert blijft een raadsel. De wat monotone performances leden eronder. Moeyaert kon dat nog rechtzetten toen hij in de rode zaal wel alle aandacht van de schijnwerpers kreeg. -

November 1995

Features BILL BRUFORD & PAT MASTELOTTO Bruford & Mastelotto's respective gigs may have headed down different musical paths in the past, but as King Crimson's navigating duo, their sights are set on the same goal—highly challenging and creative modern music. We catch up with the pair as they embark on the second leg of Crimson's international Thrak 42 tour this month. • William F. Miller JAMIE OLDAKER The Tractors are one of the newer country acts pulling in plat- inum records, but drummer Jamie Oldaker is no stranger to the big time. Heavyweights like Clapton, Stills, and Frampton have relied on his solid feel for decades. • Rick Mattingly 70 MIKE SHAPIRO "What's a nice boy like you doing in a groove like this?" He doesn't look like your typical Latin drummer—and he doesn't play like one, either. So how come Mike Shapiro is one of the most in-demand non-Brazilian "Brazilian" drummers around? • Robyn Flans 92 Volume 19, Number 11 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION EQUIPMENT NEWS 106 ROCK'N' 10 UPDATE 22 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Danny Gottlieb, NOTABLE Changuito' s Groov e Jimmy DeGrasso of BY DAVID GARIBALDI Suicidal Tendencies, 26 PRODUCT AND REBECA Ian Wallace, and CLOSE-UP Tim McGraw's Billy MAULEON-SANTANA Camber 25th Mason, plus News Anniversary Series And 108 STRICTLY C6000 Cymbals TECHNIQUE 139 INDUSTRY BY RICK VAN HORN Mirror Exercises HAPPENINGS BY JOHN MARTINEZ Zildjian Day In Prague, and more 110 JAZZ DRUMMERS' DEPARTMENTS WORKSHOP Making The African- 4 EDITOR'S Swing Connection OVERVIEW BY WOODY THOMPSON 110 ARTIST ON 8 READERS' 28 Axis Pro Hi-Hat TRACK PLATFORM And Extra Hat Steve Gadd BY CHAP OSTRANDER BY MARK GRIFFITH 14 ASK A PRO 31 1995 Consumers 120 IN THE STUDIO Chad Smith and Poll Results Carlos Vega BY RICK VAN HORN The Drummer's Studio Survival Guide: Part 8, Drum 20 IT'S 34 ELECTRONIC Microphones QUESTIONABLE REVIEW BY MARK PARSONS K&K CSM 4 Snare Mic' And CTM 3 Tom Mic' 112 CRITIQUE BY MARK PARSONS 130 CONCEPTS Django Bates, Tana Reid, Starting Over and Duffy Jackson CDs, 37 D.C.