'Study on the Assessment of UEFA's Home-Grown Player Rule'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Messi's Achievements for the 2011-2012 Season

Messi's Achievements for the 2011-2012 Season Individual Records Club (FC Barcelona) 1 The first player to score and assist in every trophy competition (6 in total) in one season. 2 The 2nd club player (after Pedro) to score in 6 official competitions in one season. 3 Leading Barça scorer in Spanish Supacopa with 8 goals. 4 Scored 35 La Liga home goals to set new club and Liga records. 5 With 14 La Liga hat-tricks, sets a new record surpassing César's 13. 6 2nd Barcelona player to win Pichichi twice (shares record with Quini). 7 Converted 10 penalties in La Liga to equal record set by Ronald Koeman (1989-1990). 8 Scored in 10 consecutive Liga games (in which he played) to equal Martin (1942/43) and Ronaldo (1996/97). 9 Equalled record set by Eto'o (2007-08) to score in 7 consecutive La Liga Away games. 10 At age 24, becomes La Liga's youngest player to score 150 goals to set club and Liga records. 11 With 214 games, beats Cocu's record (205 games) to become foreign player with most La Liga games for the club. 12 First player to score 8 hat-tricks in a single La Liga season. 13 15th October 2011: Surpasses Kubala’s 2nd place club record of 194 goals. (With a brace vs. Racing Santander at Camp Nou.) 14 29th October 2011: Scores the club's fastest La Liga hat-trick in 17 minutes (vs. Mallorca at Camp Nou.) 15 19th February 2012: Becomes the club's youngest player to play 200 La Liga games. -

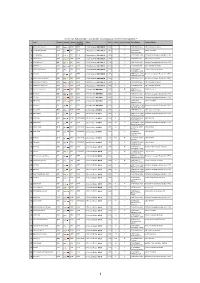

The-KA-Club-Rating-2Q-2021 / June 30, 2021 the KA the Kick Algorithms ™

the-KA-Club-Rating-2Q-2021 / June 30, 2021 www.kickalgor.com the KA the Kick Algorithms ™ Club Country Country League Conf/Fed Class Coef +/- Place up/down Class Zone/Region Country Cluster Continent ⦿ 1 Manchester City FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,928 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 2 FC Bayern München GER GER � GER UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,907 -1 UEFA Central DACH Countries Western Europe ≡ ⦿ 3 FC Barcelona ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,854 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 4 Liverpool FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,845 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 5 Real Madrid CF ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,786 -1 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 6 Chelsea FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,752 +4 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ≡ ⦿ 7 Paris Saint-Germain FRA FRA � FRA UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,750 UEFA Western France / overseas territories Continental Europe ⦿ 8 Juventus ITA ITA � ITA UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,749 -2 UEFA Central / East Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) Mediterranean Zone ⦿ 9 Club Atlético de Madrid ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,676 -1 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. FRA) ⦿ 10 Manchester United FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,643 +1 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ⦿ 11 Tottenham Hotspur FC ENG ENG � ENG UEFA 1 High Supreme ★★★★★★ 1,628 -2 UEFA British Isles UK / overseas territories ≡ ⬇ 12 Borussia Dortmund GER GER � GER UEFA 2 Primary High ★★★★★ 1,541 UEFA Central DACH Countries Western Europe ≡ ⦿ 13 Sevilla FC ESP ESP � ESP UEFA 2 Primary High ★★★★★ 1,531 UEFA Iberian Zone Romance Languages Europe (excl. -

Uefa Champions League

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2020/21 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS (First leg: 4-1) Fussball Arena München - Munich Wednesday 17 March 2021 FC Bayern München 21.00CET (21.00 local time) SS Lazio Round of 16, Second leg Last updated 14/05/2021 21:35CET UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Previous meetings 2 Match background 7 Squad list 11 Match officials 13 Fixtures and results 14 Match-by-match lineups 18 Competition facts 21 Team facts 23 Legend 25 1 FC Bayern München - SS Lazio Wednesday 17 March 2021 - 21.00CET (21.00 local time) Match press kit Fussball Arena München, Munich Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Correa 49; Lewandowski 9, 23/02/2021 R16 SS Lazio - FC Bayern München 1-4 Rome Musiala 24, Sané 42, Acerbi 47 (og) Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA FC Bayern München 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 4 1 SS Lazio 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 4 FC Bayern München - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Lewandowski 73, Müller 90+1, Thiago 4-2 Alcántara 108 ET, 16/03/2016 R16 FC Bayern München - Juventus Munich agg 6-4 (aet) Coman 110 ET; Pogba 5, Cuadrado 28 Dybala 63, Sturaro 23/02/2016 R16 Juventus - FC Bayern München 2-2 Turin 76; Müller 43, Robben 55 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers 05/11/2014 GS FC Bayern München - AS Roma 2-0 Munich Ribéry 38, Götze 64 Gervinho 66; Robben 9, 30, Götze 23, 21/10/2014 GS AS Roma - FC Bayern München 1-7 -

Uefa Champions League

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2020/21 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS National Arena - Bucharest Tuesday 23 February 2021 21.00CET (22.00 local time) Club Atlético de Madrid Round of 16, First leg Chelsea FC Last updated 14/05/2021 21:30CET UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Previous meetings 2 Match background 8 Squad list 12 Match officials 15 Fixtures and results 19 Match-by-match lineups 23 Competition facts 25 Team facts 27 Legend 29 1 Club Atlético de Madrid - Chelsea FC Tuesday 23 February 2021 - 21.00CET (22.00 local time) Match press kit National Arena, Bucharest Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Chelsea FC - Club Atlético de Savić 75 (og); Saúl 05/12/2017 GS 1-1 London Madrid Ñíguez 56 Griezmann 40 (P); Club Atlético de Madrid - Chelsea 27/09/2017 GS 1-2 Madrid Morata 60, Batshuayi FC 90+3 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Torres 36; Adrián Chelsea FC - Club Atlético de 1-3 López 44, Diego 30/04/2014 SF London Madrid agg: 1-3 Costa 60 (P), Arda Turan 72 Club Atlético de Madrid - Chelsea 22/04/2014 SF 0-0 Madrid FC UEFA Super Cup Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Chelsea FC - Club Atlético de Cahill 75; Falcao 6, 31/08/2012 F 1-4 Monaco Madrid 19, 45, Miranda 60 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Club Atlético de Madrid - Chelsea Agüero 66, 90+1; 03/11/2009 GS 2-2 Madrid FC Drogba 82, 88 Kalou 41, 52, Chelsea FC - Club Atlético de 21/10/2009 GS 4-0 London Lampard 69, Perea Madrid 90+1 (og) Home Away Final Total -

Match Press Kits

UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE - 2015/16 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Arena Khimki - Khimki Wednesday 21 October 2015 20.45CET (21.45 local time) PFC CSKA Moskva Group B - Matchday 3 Manchester United FC Last updated 22/02/2016 16:11CET UEFA CHAMPIONS LEAGUE OFFICIAL SPONSORS Previous meetings 2 Match background 4 Squad list 6 Head coach 8 Match officials 9 Fixtures and results 11 Match-by-match lineups 15 Group Standings 17 Team facts 19 Legend 22 1 PFC CSKA Moskva - Manchester United FC Wednesday 21 October 2015 - 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Match press kit Arena Khimki, Khimki Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Owen 29, Scholes 84, Manchester United FC - PFC A. Valencia 90+2; 03/11/2009 GS 3-3 Manchester CSKA Moskva Dzagoev 25, Krasić 31, V. Berezutski 47 PFC CSKA Moskva - Manchester 21/10/2009 GS 0-1 Moscow A. Valencia 86 United FC Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA PFC CSKA Moskva 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 1 1 3 4 Manchester United FC 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 1 1 0 4 3 PFC CSKA Moskva - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Manchester City FC - PFC CSKA Touré 8; Doumbia 2, 05/11/2014 GS 1-2 Manchester Moskva 34 Doumbia 65, Natcho PFC CSKA Moskva - Manchester 21/10/2014 GS 2-2 Khimki 86 (P); Agüero 29, City FC Milner 38 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Agüero 3 (P), 20, Manchester City FC - PFC CSKA Negredo 30, 51, 05/11/2013 GS 5-2 Manchester Moskva -

UEFA EURO 2016 MATCH PRESS KITS Stade De Nice - Nice Monday 27 June 2016 - 21.00CET Matchday 4 - Round of 16 England #ENGISL Iceland Last Updated 26/06/2016 03:03CET

UEFA EURO 2016 MATCH PRESS KITS Stade de Nice - Nice Monday 27 June 2016 - 21.00CET Matchday 4 - Round of 16 England #ENGISL Iceland Last updated 26/06/2016 03:03CET UEFA EURO 2016 OFFICIAL SPONSORS Match officials 2 Legend 4 1 England - Iceland Monday 27 June 2016 - 21.00CET (21.00 local time) Match press kit Stade de Nice, Nice Match officials Referee Damir Skomina (SVN) Assistant referees Jure Praprotnik (SVN) , Robert Vukan (SVN) Additional assistant referees Matej Jug (SVN) , Slavko Vinčić (SVN) Fourth official Carlos Velasco Carballo (ESP) Reserve official Roberto Alonso (ESP) UEFA Delegate Bjorn Vassallo (MLT) UEFA Referee observer Pierluigi Collina (ITA) Referee UEFA EURO Name Date of birth UEFA matches matches Damir Skomina 05/08/1976 12 108 Damir Skomina Referee since: 1992 First division: 2000 FIFA badge: 2003 Tournaments: 2013 FIFA U-20 World Cup, UEFA EURO 2012, 2007 UEFA European Under-21 Championship, 2005 UEFA European Under-19 Championship, 2005 UEFA Regions' Cup, 2003 UEFA European Under-17 Championship Finals 2012 UEFA Super Cup 2007 UEFA European Under-21 Championship UEFA European Championship matches featuring the two countries involved in this match Date Competition Stage Home Away Result Venue 15/06/2012 EURO GS-FT Sweden England 2-3 Kyiv Other matches involving teams from either of the two countries involved in this match Date Competition Stage Home Away Result Venue 14/05/2003 U17 SF Portugal England 2-2 Viseu 28/09/2003 U17 1QR Iceland Russia 0-0 Panevezys 14/06/2007 U21 GS-FT England Italy 2-2 Arnhem 06/12/2007 -

FC Basel 1893 V RC Strasbourg PRESS KIT

FC Basel 1893 v RC Strasbourg PRESS KIT St. Jakob-Park, Basle Thursday, 20 October 2005 - 19:30 local time Group E - Matchday 1 Only 140 kilometres separate them, but for the first time in UEFA club competitions, RC Strasbourg will travel from France to face Swiss side FC Basel 1893 on the opening matchday of the 2004/05 UEFA Cup group stage. For Strasbourg, the match will be their first against Swiss opposition in UEFA club competitions while Basel will look for a more positive outcome in what will be their second match against a French team after LOSC Lille Métropole ended their participation in lastseason's competition in the last 32. Basel key facts •Prior to Matchday 1 of the 2005/06 UEFA Cup group stage, Basel had played 96 matches in UEFA club competitions. •They will therefore make their 100th appearance in UEFA club competitions away to AS Roma on 14 December 2005. On the following day, fellow Swiss club Grasshopper- Club will make their 150th appearance in UEFA club competitions, away at AZ Alkmaar, as the group stage concludes. •Basel are making their seventh consecutive appearance in UEFA club competitions. •This season marks their 21st participation in UEFA club competitions since making their debut in the 1963/64 UEFA Cup Winners' Cup. •They are one of ten clubs featuring in the UEFA Cup group stage for the second consecutive season. The full list is: FC Steaua Bucuresti, Middlesbrough FC, FC Dnipro Dnipropetrovsk, AZ Alkmaar, Basel, SC Heerenveen, VfB Stuttgart, FC Zenit St. Petersburg, Besiktas JK and Sevilla FC. -

2016 Veth Manuel 1142220 Et

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Selling the People's Game Football's transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor State Veth, Karl Manuel Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 Selling the People’s Game: Football's Transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor States K. -

Spectator Information Booklet FC Barcelona V FC Porto

From the aIrPort to monaCo Bus - Spectators are asked to follow all instructions issued over the PA Price: EUR 18.50 per passenger system or on the big screens. - Any spectators who fail to observe the instructions issued will be taxi required to leave the stadium. Journey time: 70 minutes; price: EUR 90 - No replacement tickets will be issued in the event of loss or theft. hélicoptère Every 15 minutes (Héli-Air/Héli-Inter); journey time: 6 minutes the following items are strictly PROHIBITED inside the Stade Louis II: EUR 125 per passenger, single - Flags, placards, emblems or notices bearing slogans and/or images EUR 220 per passenger, return that may lead to or incite violence and/or racism - Sticks, large umbrellas, musical instruments and megaphones. - Weapons and projectiles From monaCo city Centre to the Stade Louis II - Alcoholic drinks - Fireworks, firecrackers and smoke bombs From the central train station to the Stade Louis II Access to the stadium will be refused to anyone found to be under the Bus no. 5 influence of alcohol and/or drugs. Failure to abide by these rules will Spectator Information Every 10 minutes from 06.30 to 21.00 lead to prosecution. Journey time: 7 minutes Price: EUR 1.00 per passenger Booklet By foot From the centre of Monaco (Casino): 15 minutes; direction: Fontvieille – Centre commercial From Nice to the Stade Louis II By car FC Barcelona v FC Porto - Via the motorway or “Moyenne Corniche” road: at the “Place du Jardin Exotique” (Ouest de Monaco exit), follow signs to “Fontvieille – Palais Musée” and “Centre commercial”. -

FC Steaua Bucuresti V Real Betis Balompié PRESS KIT

FC Steaua Bucuresti v Real Betis Balompié PRESS KIT Lia Manoliu, Bucharest Thursday, 9 March 2006 - 19:00 local time Round of 16 - Matchday 10 FC Steaua Bucuresti were undone by Spanish opposition at this stage of the UEFA Cup last season, but will be looking to avoid the same fate when they line up against Real Betis Balompié in the last 16. Almost 12 months ago to the day the Romanian side saw their hopes ended by Villarreal CF at El Madrigal as Argentinian playmaker Juan Román Riquelme led the home team to a 2-0 victory. •A 3-1 first-leg victory proved enough to see Steaua negotiate their way through their first knockout round tie against SC Heerenveen. Nicolae Dica, Dorin Goian and Sorin Paraschiv were all on target as Cosmin Olaroiu's team recovered from conceding an early Arnold Bruggink goal in the Netherlands and although Heerenveen pulled one goal back in Bucharest, it was Steaua that progressed. It was the continuation of some fine form in this competition by the former European champions, who breezed through the group stage after an unbeaten campaign that brought eight points, including comprehensive victories against RC Lens and Halmstads BK - both at home. •Betis were also indebted to a two-goal first-leg lead as they edged past AZ Alkmaar to secure a place in the last 32. Brazilian pair Diego Tardelli and Robert were both on target as late goals earned the side a significant advantage in Seville, which the Dutch team clawed back at the Alkmaarderhout to take the tie to extra time. -

Uefa Europa League

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE - 2013/14 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS GSP Stadium - Nicosia Thursday 19 September 2013 21.05CET (22.05 local time) Apollon Limassol FC Group J - Matchday 1 Trabzonspor AŞ Last updated 15/10/2013 11:40CET Previous meetings 2 Match background 3 Team facts 4 Squad list 6 Fixtures and results 8 Match-by-match lineups 11 Match officials 13 Legend 14 1 Apollon Limassol FC - Trabzonspor AŞ Thursday 19 September 2013 - 21.05CET, (22.05 local time) Match press kit GSP Stadium, Nicosia Previous meetings Head to Head No UEFA competition matches have been played between these two teams Apollon Limassol FC - Record versus clubs from opponents' country Apollon Limassol FC have not played against a club from their opponents' country Trabzonspor AŞ - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Cup Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers 1-0 24/08/2006 2QR Trabzonspor AŞ - APOEL FC Trabzon Riza 87 agg: 2-1 R. Fernandes 2; 10/08/2006 2QR APOEL FC - Trabzonspor AŞ 1-1 Nicosia Yattara 90 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Trabzonspor AŞ - Anorthosis 1-0 03/08/2005 2QR Trabzon Fatih Tekke 40 Famagusta FC agg: 2-3 Nikolaou 25, Frousos Anorthosis Famagusta FC - 26/07/2005 2QR 3-1 Nicosia 83, Tsitaishvili 90; Trabzonspor AŞ Fatih Tekke 75 Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA Apollon Limassol FC 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Trabzonspor AŞ 2 2 0 0 2 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 4 2 1 1 4 4 2 Apollon Limassol FC - Trabzonspor AŞ Thursday 19 September 2013 - 21.05CET, (22.05 local time) Match press kit GSP Stadium, Nicosia Match background Apollon Limassol FC will welcome Turkish opponents for the first time on matchday one in UEFA Europa League Group J, with Trabzonspor AŞ hoping to record a first victory on Cypriot soil at the third attempt. -

Uefa Europa League

UEFA EUROPA LEAGUE - 2018/19 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS (First leg: 0-3) NSK Olimpiyskyi - Kyiv Thursday 14 March 2019 FC Dynamo Kyiv 18.55CET (19.55 local time) Chelsea FC Round of 16, Second leg Last updated 12/03/2019 16:04CET Previous meetings 2 Match background 5 Team facts 8 Squad list 11 Fixtures and results 13 Match-by-match lineups 17 Match officials 20 Legend 21 1 FC Dynamo Kyiv - Chelsea FC Thursday 14 March 2019 - 18.55CET (19.55 local time) Match press kit NSK Olimpiyskyi, Kyiv Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA Europa League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Pedro Rodríguez 17, 07/03/2019 R16 Chelsea FC - FC Dynamo Kyiv 3-0 London Willian 65, Hudson- Odoi 90 UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Dragović 34 (og), 04/11/2015 GS Chelsea FC - FC Dynamo Kyiv 2-1 London Willian 83; Dragović 78 20/10/2015 GS FC Dynamo Kyiv - Chelsea FC 0-0 Kyiv Home Away Final Total Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA FC Dynamo Kyiv 1 0 1 0 2 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 3 0 1 2 1 5 Chelsea FC 2 2 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 3 2 1 0 5 1 FC Dynamo Kyiv - Record versus clubs from opponents' country UEFA Champions League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Manchester City FC - FC 0-0 15/03/2016 R16 Manchester Dynamo Kyiv agg: 3-1 Buyalskiy 59; Agüero FC Dynamo Kyiv - Manchester 24/02/2016 R16 1-3 Kyiv 15, David Silva 40, City FC Touré 90 UEFA Europa League Date Stage Match Result Venue Goalscorers Yarmolenko 21, Teodorczyk 35, 5-2 Miguel Veloso 37, 19/03/2015 R16 FC Dynamo Kyiv - Everton FC Kyiv agg: 6-4 Gusev 56, Antunes 76; R.