Thoughts on Historical Aircraft Preservation.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FEBRUARY 2012 ISSUE No

MILITARY AVIATION REVIEW FEBRUARY 2012 ISSUE No. 291 EDITORIAL TEAM COORDINATING EDITOR - BRIAN PICKERING WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL”[email protected]” BRITISH REVIEW - GRAEME PICKERING 15 ASH GROVE, BOURNE, LINCS PE10 9SG TEL NO. 01778 421788 EMail "[email protected]" FOREIGN FORCES - BRIAN PICKERING (see Co-ordinating Editor above for address details) US FORCES - BRIAN PICKERING (COORDINATING) (see above for address details) STATESIDE: MORAY PICKERING 18 MILLPIT FURLONG, LITTLEPORT, ELY, CAMBRIDGESHIRE, CB6 1HT E Mail “[email protected]” EUROPE: BRIAN PICKERING OUTSIDE USA: BRIAN PICKERING See address details above OUT OF SERVICE - ANDY MARDEN 6 CAISTOR DRIVE, BRACEBRIDGE HEATH, LINCOLN LN4 2TA E-MAIL "[email protected]" MEMBERSHIP/DISTRIBUTION - BRIAN PICKERING MAP, WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL.”[email protected]” ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION (Jan-Dec 2012) UK £40 EUROPE £48 ELSEWHERE £50 @MAR £20 (EMail/Internet Only) MAR PDF £20 (EMail/Internet Only) Cheques payable to “MAP” - ALL CARDS ACCEPTED - Subscribe via “www.mar.co.uk” ABBREVIATIONS USED * OVERSHOOT f/n FIRST NOTED l/n LAST NOTED n/n NOT NOTED u/m UNMARKED w/o WRITTEN OFF wfu WITHDRAWN FROM USE n/s NIGHTSTOPPED INFORMATION MAY BE REPRODUCED FROM “MAR” WITH DUE CREDIT EDITORIAL - Welcome to the February edition of MAR! This issue sees the United Kingdom 2012 Review from Graeme - a month later than usual due to his work commitments. Because of this the issue is somewhat truncated in the Foreign Section department, but we should catch up with the March issue. -

OCTOBER 2014 ISSUE No

MILITARY AVIATION REVIEW OCTOBER 2014 ISSUE No. 323 EDITORIAL TEAM COORDINATING EDITOR - BRIAN PICKERING WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL”[email protected]” BRITISH REVIEW - MICK BOULANGER 27 Tudor Road, Heath Town, Wolverhampton, West Midlands WV10 0LT TEL NO. 0770 1070537 EMail "[email protected]" FOREIGN FORCES - BRIAN PICKERING (see Co-ordinating Editor above for address details) US FORCES - BRIAN PICKERING (COORDINATING) (see above for address details) STATESIDE: MORAY PICKERING 19 RADFORD MEADOW, CASTLE DONINGTON, DERBY DE74 2NZ E Mail “[email protected]” EUROPE: BRIAN PICKERING OUTSIDE USA: BRIAN PICKERING See address details above OUT OF SERVICE - ANDY MARDEN 6 CAISTOR DRIVE, BRACEBRIDGE HEATH, LINCOLN LN4 2TA E-MAIL "[email protected]" MEMBERSHIP/DISTRIBUTION - BRIAN PICKERING MAP, WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL.”[email protected]” ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION (Jan-Dec 2015) UK £40 EUROPE £55 ELSEWHERE £60 @MAR £20 (EMail/Internet Only) MAR PDF £20 (EMail/Internet Only) Cheques payable to “MAP” - ALL CARDS ACCEPTED - Subscribe via “www.mar.co.uk” ABBREVIATIONS USED * OVERSHOOT f/n FIRST NOTED l/n LAST NOTED n/n NOT NOTED u/m UNMARKED w/o WRITTEN OFF wfu WITHDRAWN FROM USE n/s NIGHTSTOPPED INFORMATION MAY BE REPRODUCED FROM “MAR” WITH DUE CREDIT EDITORIAL Thank you to everyone who has already sent in their 2015 subscriptions - and a further thank you to everyone who made the cheques payable to “B Pickering” and not to MAP (onlt three of the latter so far! For those of you who are still to subscribe for 2015 an early renewal would be greatly appreciated, there is an amazing amount of extra administrative work to do in the first two weeks of January to get the 2015 year on track, as well as getting the January MAR produced. -

Rare & Second-Hand Aviation Books

Dec 2014 RARE & SECOND-HAND AVIATION BOOKS Favourite Racing Aeroplanes October 2014 THE COMET’s 80th ANNIVERSARY! BRIAN COCKS 18 WOODGATE HELPSTON PETERBOROUGH PE6 7EDTel 01733-252791 e-mail; [email protected] WEBSITE; www.aviationbookhouse.co.uk Greetings Another catalogue! – but it may be the last! WOULD EVERYONE RECEIVING THIS PLEASE GET IN TOUCH, EVEN IF NOT ORDERING ANYTHING, SO THAT I CAN ASSESS YOUR CATALOGUE NEEDS. The response to catalogues has diminished again since the last one and I have restricted the size, particularly of the main sections. And I offer again a 10% discount for orders of 5 or more hard-backs. The following are my usual conditions. This catalogue is NOT a complete stock list. Although the “Books in Series”section shows all titlesI in stock, the main book categories show only a small selection of my much bigger stocks (visible on my website).I also have duplicates of some of those listed, usually less fine and at lower prices. I am always pleased to welcome visitors to Helpston, preferably by prior appointment a day or so beforehand. Messages can be left on my answering system when I'm not available or by e-mail. Except where otherwise stated, books listed are 8vo or thereabouts, are not illustrated and have dust-wrappers. The main catalogue reference numbers are all new - if requesting books from older catalogues please quote the date. (The “UBN” numbers quoted - unique book numbers - always stay with the same title – they are used mainly for our system reference.) TERMS; Please order without sending payment. -

Survey of WWII Remains at Findo Gask Airfield, Clathymore, Perth And

Survey of WWII remains at Findo Gask Airfield, Clathymore, Perth and Kinross David Bowler Background Survey method Introduction A measured plan of the site and all visible remains had already been made by A & J Stephen. This was used as A & J Stephen (Builders) Ltd commissioned SUAT Ltd a base plan, and all the features on it were numbered to undertake a survey of the surviving WWII airfield re- and listed. The site was then visited by D P Bowler of mains at Clathymore, in advance of residential redevel- SUAT, on 9th December 2003, and 5th, 6th, 9th, 11th, opment of the site. 12th, 13th February 2004. Some of these visits were less The airfield was known as Findo Gask, and is lo- than a full day, due to bad weather or failing light. All cated on Clathymore Farm, at NO 0116 2129. The site the features were described, photographed and where lies on high, fairly level ground on the Gask Ridge, appropriate, measured. c 10 km to the W of Perth, c 5 km S of Methven, and Extensive use was made of digital photography, with c 1 km to the N of the well-known Gask Ridge Roman some 498 digital images being taken, listed and fully de- frontier (Woolliscroft 2002). The site has clear unob- scribed, to record every feature that was capable of be- structed views all around, especially WSW, dominated ing photographed. Colour slide and monochrome film by Ben Vorlich, and ENE, up towards Strathmore. The photographs were also taken of selected features. present survey was given the project code MV02, (refer- Many of the 66 features recorded were rather simple ring to the nearby village of Methven). -

MAY 2012 ISSUE No

MILITARY AVIATION REVIEW MAY 2012 ISSUE No. 294 EDITORIAL TEAM COORDINATING EDITOR - BRIAN PICKERING WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL”[email protected]” BRITISH REVIEW - MICK BOULANGER 27 Tudor Road, Heath Town, Wolverhampton, West Midlands WV10 0LT TEL NO. 0770 1070537 EMail "[email protected]" FOREIGN FORCES - BRIAN PICKERING (see Co-ordinating Editor above for address details) US FORCES - BRIAN PICKERING (COORDINATING) (see above for address details) STATESIDE: MORAY PICKERING 18 MILLPIT FURLONG, LITTLEPORT, ELY, CAMBRIDGESHIRE, CB6 1HT E Mail “[email protected]” EUROPE: BRIAN PICKERING OUTSIDE USA: BRIAN PICKERING See address details above OUT OF SERVICE - ANDY MARDEN 6 CAISTOR DRIVE, BRACEBRIDGE HEATH, LINCOLN LN4 2TA E-MAIL "[email protected]" MEMBERSHIP/DISTRIBUTION - BRIAN PICKERING MAP, WESTFIELD LODGE, ASLACKBY, SLEAFORD, LINCS NG34 0HG TEL NO. 01778 440760 E-MAIL.”[email protected]” ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION (Jan-Dec 2012) UK £40 EUROPE £48 ELSEWHERE £50 @MAR £20 (EMail/Internet Only) MAR PDF £20 (EMail/Internet Only) Cheques payable to “MAP” - ALL CARDS ACCEPTED - Subscribe via “www.mar.co.uk” ABBREVIATIONS USED * OVERSHOOT f/n FIRST NOTED l/n LAST NOTED n/n NOT NOTED u/m UNMARKED w/o WRITTEN OFF wfu WITHDRAWN FROM USE n/s NIGHTSTOPPED INFORMATION MAY BE REPRODUCED FROM “MAR” WITH DUE CREDIT EDITORIAL Welcome to the May issue of MAR - and welcome to the new UK Section Editor. Mick Boulanger is now editing the UK Section of MAR, after the long reign of Graeme, and has made an excellent start with his May section. Please send in all your UK reports (except for the US Bases at Fairford, Lakenheath and Mildenhall which still go to me - Brian) to Mick at the various addresses listed above. -

I Nomi Degli Aerei Da Combattimento Della Royal Air Force E Della Fleet Air Arm

Giuseppe Brincat I nomi degli aerei da combattimento della Royal Air Force e della Fleet Air Arm L’idea di elevarsi da terra per osservare o recar danno al nemico sarà venuta a molti generali durante i conflitti armati fin dai secoli più remoti, ma la possibilità di avvalersi di aeromobili a scopo militare fu realizzata soltanto con l’invenzione dei palloni aerostatici. I primi ad utilizzarli furono i francesi, nel 1794 a Fleurus, quando il pallone di ricognizione L’Entreprenant sorvolò il campo di battaglia per osservare i movimenti delle truppe austriache. Nell’Ottocento furono apportati alcuni miglioramenti ma i dirigibili rimasero ingombranti e preda facile dell’artiglieria. Lo sviluppo tecnico dell’aviazione risultò molto lento e bisognava aspettare i primi anni del Novecento per vedere decollare e atterrare sano e salvo un aeroplano vero e proprio. Il primo volo di un congegno più pesante dell’aria, dotato di ali e di un motore con propulsione a elica e capace di essere controllato, si attribuisce ai fratelli Wilbur e Orville Wright che nel 1903, dopo alcuni esperimenti con alianti, riuscirono a staccarsi da terra e coprire 300 metri in 59 secondi. Da quel momento il progresso fu rapidissimo, tanto che in un decennio i biplani si moltiplicarono in vari paesi. Il primato del volo militare spetta all’Italia. Il Corpo Aeronautico Militare, formato nel 1911 per la campagna di colonizzazione della Libia, eseguì il primo volo di ricognizione il 23 ottobre di quell’anno e il primo bombardamento soltanto pochi giorni dopo, il 1 novembre, sulle postazioni ottomane. La prima bomba fu lanciata dal pilota Giulio Gavotti sull’oasi di Ain Zara in Libia da un monoplano costruito in Germania che aveva il nome di Taube, che vuol dire ‘colomba’, un uccello che ironicamente spesso simboleggia la pace. -

A Battle of Britain Hero Area of the Crash and the Distance from the Red Tower (Torri La Mar), Both Confirm That the Hurricane in the Field at Qammieh Was Corfe's

AT.U - Ot'. ~ 1'1 lit f tm: .lt I~'IA 1 tA THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA -THE StiNDAYTIMES OF-MALTA- APRIL 15, ~018 I -57 1 T ' 4 1t :to ?51' C' s .,. q r•rro a'·a· LIFE& WELLBEING HISTORY Douglas Corte during the Battle of Britain. His name can be seen engraved on the Part of the Hurricane wing still showing traces of paint. microphone. PHOTO: WWW.TRIBUTE-TO-THE-FEW.CO.UK A Hawker Hurricane stationed in Malta. PHOTO: PININTEREST.COM W/0 Gorst (sic) (229) & P/0 Pawson (601 or 603) both crashed and dead. The former at 313350 (150 yds Torri la Mar) the latter at 3930 (Hill162)". The map reference 313350, which marks the A Battle of Britain hero area of the crash and the distance from the Red Tower (Torri la Mar), both confirm that the Hurricane in the field at Qammieh was Corfe's. But who was Douglas Corfe? Corfe was a hero in the Battle of Britain. He became well known when his photo, taken in - his Spitfire cockpit, appeared in many maga shot down over Malta zines, newspapers and books. Corfe fought during the Battle of Britain with JEFFREY SAMMUT The British Services took away the dead A few years later, all the wreckage was were found in the soil and in the rubble 610 Squadron, which flew Spitfires. On August pilot. The farmers petitioned the British removed from the site by government walls. An interesting find was a piece of cast 14, 1940, he wrote in his combat report: government for compensation for the dev officials. -

April 2012 NUMBER 41 €3.00

April 2012 NUMBER 41 €3.00 NEWSPAPER POST Din l-Art Ħelwa is a non-governmental organisation whose objective is to The Council safeguard the cultural heritage and natural environment of the nation. Din l-Art Ħelwa functions as the National Trust of Malta, restoring cultural heritage sites on behalf of the State, the Church, and private owners and managing and maintaining those sites for the benefi t of the general public. Founder President Judge Maurice Caruana Curran Din l-Art Ħelwa strives to awaken awareness of cultural heritage and environmental matters by a policy of public education and by highlighting development issues to ensure that the highest possible standards are maintained THE COUNCIL 2011-13 and that local legislation is strictly enforced. Executive President Simone Mizzi Vice-Presidents Martin Scicluna Professor Luciano Mulé Stagno Hon. Secretary General George Camilleri Hon. Treasurer Victor Rizzo Members Professor Anthony Bonanno Carolyn Clements Ian Camilleri Judge Maurice Caruana Curran The views expressed in Cettina Caruana Curran VIGILO Maria Grazia Cassar are not necessarily Joseph F Chetcuti those of VIGILO Josie Ellul Mercer Din l-Art Ħelwa is published in Judge Joe Galea Debono April and October Martin Galea VIGILO e-mail: Cathy Farrugia Din l-Art Ħelwa [email protected] Dr Stanley Farrugia Randon has reciprocal membership with: Dame Blanche Martin The National Trust of England, COPYRIGHT by the PUBLISHER Dane Munro Din l-Art Ħelwa Patricia Salomone Wales & Northern Ireland John Sarè The National Trust for Scotland EDITOR Joanna Spiteri Staines DESIGN & LAYOUT Edward Xuereb The Barbados National Trust JOE AZZOPARDI PROOF READER The National Trust of Australia JUDITH FALZON The Gelderland Trust for PHOTOGRAPHS Historic Houses If not indicated otherwise photographs are by Din l-Art Ħelwa The Gelderland ‘Nature Trust’ JOE AZZOPARDI National Trust of Malta 133 Melita Street Din l-Art Ħelwa PRINTED BY is a member of: Best Print Co. -

Hawker Hurricane

Last updated 1 July 2021 ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| HAWKER HURRICANE ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| W/05422 •Mk. I L1592 built Brooklands 5.38: RAF BOC 3.6.38/44 attacked by Bf 109E, forced landing near Croydon 18.8.40 (repaired RAF Henlow 10.40, returned to service) RAF Air Historical Branch, Stanmore 45/54 (stored dism. various locations, then display exhibit as “DT-A” later “US-D”) Science Museum, South Kensington, London 16.12.54/20 (stored Sydenham for Science Museum 54/60, moved to Dunsford 22.8.60 for rest by Hawker as “KW-Z”, displ. Science Museum from 5.61 as RAF “L1592/KW-Z”) ________________________________________________________________________________________ W/05436 Mk. I L1606 G-AFKX Hawker Aircraft Ltd, Langley 29.10.38/41 (engine and propeller testbed 39/41) retired, struck-off civil register 4.5.41 ________________________________________________________________________________________ - • Mk. I L1639 shot down by Bf 109s near Abbeville, France 14.5.40 (crash hulk excavated from crash site .99) Cambridge Bomber & Fighter Society, Little Gransden 02/20 (rest. to taxying condition in workshop at Little Gransden, new fuselage frame fitted with genuine Hurricane -

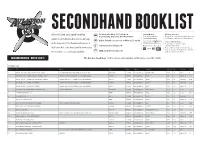

Secondhand Booklist

SECONDHAND BOOKLIST All books listed are in good condition The Aviation Bookshop, 31-33 Vale Road, Payment Methods UK Postage & Packing Royal Tunbridge Wells, Kent, TN1 1BS, ENGLAND Cheques made payable to Postage will be charged at cost and all orders over complete with dust jackets and no damage The Aviation Bookshop £50.00 will be sent post free to all UK addresses 01892 539284 (international: +44 18 92 53 92 84) or you can pay via using Overseas Delivery Charges to the book itself. The books are listed on a [email protected] Postal charges are made at cost price [email protected] All major credit cards accepted to The Aviation Bookshop. first come first serve basis, but in some cases We are unable to detail exact postal charges as orders are treated individually and the applicable www.aviation-bookshop.com we may have a second copy available. charge is calculated accordingly. CATALOGUE NUMBER 16 – WINTER 2020/21 The Aviation Bookshop - at the service of all aviation enthusiasts since the 1940s AEROMODELLING Reference Title Subtitle Author Format Subject Publisher Published Pages Condition £ Price 1 AIRCRAFT AND HELICOPTERS IN SWEDISH PUBLIC SERVICE FLYGPLANS-RITNINGAR 7 - SCALE DRAWINGS IN 1:72 & 1:144 KARLSTROM SOFTBACK AEROMODELLING ALLT OM HOBBY 1994 96 GOOD 15.00 2 AIRCRAFT ARCHIVE - FIGHTERS OF WORLD WAR TWO VOLUME 1 DETAILED COLLECTION OF ORIGINAL SCALE AIRCRAFT DRAWINGS VARIOUS SOFTBACK AEROMODELLING ARGUS 1988 96 VERY GOOD 10.00 3 AIRCRAFT ARCHIVE - FIGHTERS OF WORLD WAR TWO VOLUME 2 DETAILED COLLECTION OF -

Military Aircraft Markings Update Number 22, November/December 2006

Military Aircraft Markings Update number 22, November/December 2006. Serial Type (other identity) [code] Owner/operator, location or fate D7889 Bristol F2b Fighter (G-AANM/BAPC 166) Sold to Canada, December 2006 K2075 Isaacs Fury II (G-BEER) Privately owned, Combrook, Warks N6473 DH82A Tiger Moth (G-AOBO) Privately owned, Orbigny, France N6537 DH82A Tiger Moth (G-AOHY) Privately owned, France Z2389 Hawker Hurricane IIA [XR-T] Brooklands Museum, Weybridge KB994 Avro 683 Lancaster B X (G-BVBP) <ff> Sold to Australia, November 2006 NJ673 Auster 5D (G-AOCR) Privately owned, Shennington RN201 VS379 Spitfire FR XIV (SG-31/ SG-3 /G-BSKP) [D] Sold to the USA, October 2006 TA805 VS361 Spitfire HF IX (G-PMNF) [FX-M] Privately owned, Biggin Hill VP293 Avro 696 Shackleton T4 [A] <ff> City of Norwich Aviation Museum VW957 DH103 Sea Hornet NF21 <rf> Privately owned, Chelmsford WA591 Gloster Meteor T7 (7917M/G-BWMF) [W] Air Atlantique Classic Flight, Coventry WF219 Hawker Sea Hawk F1 FAA Museum, stored RNAS Yeovilton WJ368 Auster AOP6 (G-ASZX) Privately owned, Eggesford WJ721 EE Canberra TT18 [21] <ff> No 2405 Det Flt ATC, Gairlock WJ866 EE Canberra T4 MoD COD, Bicester WL360 Gloster Meteor T7 (7920M) [G] Sold to Malta Aviation Museum, Nov 2006 WP321 Percival P57 Sea Prince T1 (G-BRFC) Privately owned, Bournemouth WP784 DHC1 Chipmunk T10 <ff> Privately owned, Twyford WS774 Gloster Meteor NF14 (7959M) Sold to Malta Aviation Museum, Nov 2006 WV903 Hawker Sea Hawk FGA4 (8153M) [128/C] Privately owned, Ilminster, Somerset WW421 Percival P56 Provost T1 (WW450/G-BZRE/7689M)