Railways in the North East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

00 Primeras Paginas Rha5

RHA, Vol. 5, Núm. 5 (2007), 57-71 ISSN 1697-3305 RAILWAYS AND THE STATE IN THE UK Gerald W. Crompton* Recibido: 11 Junio 2007 / Revisado: 8 Septiembre 2007 / Aceptado: 30 Septiembre 2007 The UK was unusual in the absence of direct until the appearance of the internal combustion inputs by the state into the design, building or engine, increasingly important to the economy, financing of its railway system. This did not mean and increasingly dominant as a mode of transport. that the railways were ‘exemplars of Victorian pri- Furthermore, the industry was concentrated and vate enterprise, unfettered by the state’1. Each new the bigger companies were extremely large in rela- company required legislation, often contested, tion to their counterparts in other sectors. By 1870 which accounted for about 5% of all development the ‘big four’ accounted for 44% of railway turno- costs2. This factor, along with the high cost of land, ver. By 1905 the Midland had a paid-up capital ten and parochial taxation, helped to impose a long- times as great as the largest manufacturing firm. lasting over-capitalisation on the industry in its One authority has judged that price competition, first few decades the nineteenth century also left a which had been active in the early decades, was legacy of public regulation which had a uniquely ‘virtually dead by 18703. It is hardly surprising that high impact on the railways. fear of the consequences of railway monopoly took Before 1900 governments had taken powers root in the nineteenth century. to require the running of cheap trains for the bene- Beyond these broad aims, public policy had fit of workmen (1844 and 1883), the publication lacked consistency. -

TRACKS Binders: with 768 Pages of Valuable Information Now Contained Within a Years Issues of TRACKS It Is Worth Keeping Your Copies Protected

TTRRAACCKKSS Inter City Railway Society - February 2016 Inter City Railway Society founded 1973 www.intercityrailwaysociety.org Volume 44 No.2 Issue 518 February 2016 The content of the magazine is the copyright of the Society No part of this magazine may be reproduced without prior permission of the copyright holder President: Simon Mutten (01603 715701) Coppercoin, 12 Blofield Corner Rd, Blofield, Norwich, Norfolk NR13 4RT Chairman: Carl Watson - [email protected] Mob (07403 040533) 14, Partridge Gardens, Waterlooville, Hampshire PO8 9XG Treasurer: Peter Britcliffe - [email protected] (01429 234180) 9 Voltigeur Drive, Hart, Hartlepool TS27 3BS Membership Sec: Colin Pottle - [email protected] (01933 272262) 166 Midland Road, Wellingborough, Northants NN8 1NG Mob (07840 401045) Secretary: Stuart Moore - [email protected] (01603 714735) 64 Blofield Corner Rd, Blofield, Norwich, Norfolk NR13 4SA Events: Louise Watson - [email protected] Mob (07921 587271) 14, Partridge Gardens, Waterlooville, Hampshire PO8 9XG Magazine: Editor: Trevor Roots - [email protected] (01466 760724) Mill of Botary, Cairnie, Huntly, Aberdeenshire AB54 4UD Mob (07765 337700) Sightings: James Holloway - [email protected] (0121 744 2351) 246 Longmore Road, Shirley, Solihull B90 3ES Photo Database: John Barton Website: Trevor Roots - [email protected] contact details as above Books: Publications Manager: Carl Watson -

Doncaster's Wheels, Wings & Moving Things

Doncaster's Wheels, Wings & Moving Things History | Health | Happiness Doncaster’s Wheels, Wings and Moving Things Introduction: Doncaster has a strong industrial and railway heritage; some of the most famous locomotives in the world were built and designed at ‘the Plant.’ Doncaster hosted one of the world’s first aviation meetings in 1909 and the first British fighter jets to be used in the Second World War, Gloster Meteors, were stationed at RAF Finningley, what is now a busy and expanding Robin Hood Airport. Ford cars also once rolled off production lines in the town. Perhaps you have your own memories of some of these great moving machines? What Above: Approach to Doncaster station. memories do wheels bring back for you? Your Image: Heritage Doncaster first bike, your first car, rail journeys to the seaside? In this pack you will find a variety of activities that relate to Doncaster’s history of wheels, wings and moving things. We hope you enjoy this opportunity to reflect. Please feel free to share your thoughts and memories by emailing: [email protected]. We’d love to hear from you! Contents Within the sections below you will find a variety of activities. Page 2: A Coaching Town Fit for the Races Page 3-10: Doncaster’s Railway Heritage Pages 11-13: Give us a Coggie/ Doncaster Cycling Stories/On your Bike Pages 14-15: Ford in Doncaster/British Made Ford Cars Page 16: Music on the Move Quiz Page 17: Word Search Page 18-19: Trams and Trolleybuses Page 20: Guess the Wheels, Wings and Moving Things Page 21: Crossword Page 22: England’s First Flying Show! Page 23: The Flying Flea The Gloster Meteor in level flight, 1st January 1946. -

East Coast Modern a Route for Train Simulator – Dovetail Games

www.creativerail.co.uk East Coast Modern A Route for Train Simulator – Dovetail Games Contents A Brief History of the Route Route Requirements Scenarios Belmont Yard – York Freight Doncaster – Newark Freight Grantham – Doncaster Non-Stop Hexthorpe – Marshgate Freight Newark – Doncaster Works Peterborough – Tallington Freight Peterborough – York Non-Stop Selby – York York – Doncaster Works Operating Notices Acknowledgements © Copyright CreativeRail. All rights reserved. 2018. www.creativerail.co.uk A Brief History of the Route The first incarnation of the East Coast Main Line dates back to 1850 when London to Edinburgh services became possible on the completion of a permanent bridge over the River Tweed. However, the route was anything but direct, would have taken many, many hours and would have been exhausting. By 1852, the Great Northern Railway had completed the 'Towns Line' between Werrington (Peterborough) and Retford, which saw journey times between York and London of five hours. Edinburgh to London was a daunting eleven. Over time, the route has endured harsh periods, not helped by two world wars. It only benefited from very little improvement. Nevertheless, journey times did shrink. Names and companies synonymous with the route, such as, LNER and Gresley have secured their place in history, along with the most famous service - 'The Flying Scotsman'. Motive power also developed with an ever increasing calibre including A3s, A4s Class 55s and HSTs that have powered expresses through the decades. The introduction of HST services in 1978 saw the Flying Scotsman reach Edinburgh in only five hours. A combination of remodelling, track improvements and full electrification has seen a further reduction to what it is today, which sees the Scotsman complete the 393 miles in under four and a half hours in the capable hands of Class 91 and Mk4 IC225 formations. -

A Round up of Recent Activities in Our Sections the Journal July 2017

Section Activities A round up of recent activities in our Sections AS PUBLISHED IN The Journal July 2017 Volume 135 Part 3 INSTITUTION MATTERS Sections BIRMINGHAM CROYDON & BRIGHTON DARLINGTON & NORTH EAST EDINBURGH Our online events calendar holds all GLASGOW of our Section meetings. IRISH LANCASTER, BARROW & CARLISLE You’ll also find full contact details on LONDON our website. MANCHESTER & LIVERPOOL MILTON KEYNES NORTH WALES NOTTINGHAM & DERBY SOUTH & WEST WALES THAMES VALLEY WESSEX WEST OF ENGLAND WEST YORKSHIRE YORK 2 INSTITUTION MATTERS LANCASTER, BARROW & SOUTH & WEST WALES SECTION CARLISLE Chairman Andy Franklin Chairman John Parker Secretary Andrew Wilson Secretary Philip Benzie 07974 809639 CONTACTS 01704 896924 [email protected] [email protected] MEETING VENUE Network Rail Office, Fifth floor, 5 Callaghan BIRMINGHAM MEETING VENUES Station Hotel, Butler Street, Preston, PR1 Square, Cardiff at 17:15 Sections Chairman David Webb 8BN (adjacent to Preston station) 17:30 for Deputy Chairman Craig Green 18:00; Royal Station Hotel, Carnforth, LA5 9BT Secretary Richard Quigley 07715 132267 (adjacent to Carnforth station) 17:30 for 18:00; THAMES VALLEY [email protected] Network Rail, North Union House, Christian Chairman Jeremy Smith Road, Preston, PR1 2NB at 1600 for 16:30; MEETING VENUES Secretary Malcolm Pearce The Wellington Pub, 37 Bennetts Hill, Network Rail, Upperby Yard, Tyne Street, 01635 550326 / 07967 667019 Birmingham, B2 5SN at 17:00 Carlisle CA1 2NP at 1600 for 16:30 [email protected] -

The Unauthorised History of ASTER LOCOMOTIVES THAT CHANGED the LIVE STEAM SCENE

The Unauthorised History of ASTER LOCOMOTIVES THAT CHANGED THE LIVE STEAM SCENE fredlub |SNCF231E | 8 februari 2021 1 Content 1 Content ................................................................................................................................ 2 2 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 5 3 1975 - 1985 .......................................................................................................................... 6 Southern Railway Schools Class .................................................................................................................... 6 JNR 8550 .......................................................................................................................................................... 7 V&T RR Reno ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Old Faithful ...................................................................................................................................................... 9 Shay Class B ..................................................................................................................................................... 9 JNR C12 ......................................................................................................................................................... 10 PLM 231A ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Alarm As New East Coast Franchise Fails to Protect Vital Morpeth Services

nd SENRUG Press Release: 22 April 2014 ALARM AS NEW EAST COAST FRANCHISE FAILS TO PROTECT VITAL MORPETH SERVICES SENRUG, the group that campaigns for better rail services in South East Northumberland, is expressing its concern that the specification for the new East Coast Main Line rail service, recently published by the Department for Transport, does not protect vital services at Morpeth. The franchise sets out the minimum service levels the new operator, who will take over running the line from March 2015, will need to provide. Three companies are currently bidding for the contract. Whilst whoever wins can provide additional services over and above the franchise specification if they wish, they can withdraw any service that is not “franchise protected”. SENRUG Chair Dennis Fancett said the franchise specification, now available on the government website, is a long and complex document. “But as far as we can see, the all important early morning Monday to Friday southbound connection from Morpeth to the Flying Scotsman service with current arrival in London by 09:40 is no longer a specified requirement. The earliest requirement for arrival in London from Morpeth reverts to 10:05, making that 10:00 business meeting impossible once again. Although the operator is required to retain the two direct services from Morpeth to London, it is not stipulated that one of them must offer a connection at Newcastle to the Flying Scotsman. And the Flying Scotsman itself will only be required to arrive by 09:50 (current arrival time 09:40)”. Additionally, the later northbound Friday only service from London at 19:30 is not a specified requirement. -

U DYE WB Yeadon London & North Eastern 1847-1997 Railway Collection

Hull History Centre: W.B. Yeadon London & North Eastern Railway collection U DYE W.B. Yeadon London & North Eastern 1847-1997 Railway collection Historical background: Willie Brayshaw Yeadon was born in Yeadon in the West Riding of Yorkshire on 28 June 1907. After his schooldays, he trained to become a mechanical engineer, and started work with Bradford Dyers, but was unfortunately made redundant in 1930 following the onset of terrible trading conditions. In 1931 he joined JH Fenner Ltd in Hull ('makers of improved beltings'), eventually becoming Sales Manager and then Marketing Manager, until his official retirement in 1972. He died at the age of 89 on 16 January 1997 in Hull Royal Infirmary after a short illness. By then he had become probably the country's leading authority on the London & North Eastern Railway and its locomotives. Indeed, Eric Fry, honorary editor of 'Locomotives of the LNER', writing in the 'Railway Observer' in March 1997, described him as possibly 'the foremost locomotive historian of all time'. Willie Yeadon's earliest railway interest had been the London & North Western Railway, with visits and family holidays to Shap summit and Tebay. On his removal to Hull, however, the London & North Eastern Railway became his main preoccupation, and he was particularly inspired by the development and progress of Sir Nigel Gresley's Pacific class locomotives during the 1930s. He began to collect railway photographs in 1933, and continued his interest after railway nationalisation in 1948. The British Railways modernisation programme undertaken from the mid - 1950s prompted him to investigate and record the history of every LNER locomotive. -

Trains Galore

Neil Thomas Forrester Hugo Marsh Shuttleworth (Director) (Director) (Director) Trains Galore 15th & 16th December at 10:00 Special Auction Services Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL Telephone: 01635 580595 Email: [email protected] Bob Leggett Graham Bilbe Dominic Foster www.specialauctionservices.com Toys, Trains & Trains Toys & Trains Figures Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. If you are happy with our service, please write a Google review Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price 7. Graham Farish and Peco N Gauge 13. Fleischmann N Gauge Prussian Train N Gauge Goods Wagons and Coaches, three cased Sets, two boxed sets 7881 comprising 7377 T16 Graham Farish coaches in Southern Railway steam locomotive with five small coaches and Livery 0633/0623 (2) and a Graham Farish SR 7883 comprising G4 steam locomotive with brake van, together with Peco goods wagons tender and five freight wagons, both of the private owner wagons and SR all cased (24), KPEV, G-E, boxes G (2) Day 1 Tuesday 15th December at 10:00 G-E, Cases F (28) £60-80 Day 1 Tuesday 15th December at 10:00 £60-80 14. Fleischmann N Gauge Prussian Train Sets, two boxed sets 7882 comprising T9 8177 steam locomotive and five coaches and 7884 comprising G8 5353 steam locomotive with tender and six goods wagons, G-E, Boxes F (2) £60-80 1. -

FLYING SCOTSMAN’ LNER 4-6-2 1:32 SCALE • 45 Mm GAUGE

‘FLYING SCOTSMAN’ LNER 4-6-2 1:32 SCALE • 45 mm GAUGE ENGINEERING SAMPLE SHOWN Sir Nigel Gresley was renowned for his Pacific express locomo- SPECIFICATIONS tives, the first of which, the A1 class, entered service in 1922. The A3 was a modification of the A1 and over time all of the sur- Scale 1:32 viving A1s were rebuilt as A3s. No. 4472 “Flying Scotsman” was Gauge 45 mm built in 1923 and went on to become one of the most famous Mini. radius 6ft 6in. (2 m) steam locomotives in the world setting many records along the way. After the war it was renumbered 103 then, after the nation- Dimensions 26.5 x 3.5 x 5.25 in. alisation, carried the number 60103, remaining in service on the Construction Brass & stainless steel East Coast mainline until 1963. During its service career it cov- Electric Version ered over 2,000,000 miles and travelled non-stop from London Power 0~24V DC to Edinburgh in 8 hours. It was sold into private ownership, was Full cab interior design sent to America and Australia and is today under restoration at Features The National Railway Museum in York. Constant lighting Live Steam Version We are currently developing a 1:32 scale live steam version of our very successful electric LNER A3 Class “Flying Scotsman”. Power Live steam, butane fired The model is gas-fired with slide valves and has all the features Boiler Copper the Gauge 1 fraternity have come to expect from an Accucraft Valve gear Walschaerts valve gear locomotive. -

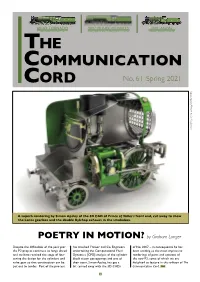

The Communication Cord Is Rather “P2 from Acorns Grow”

60163 TORNADO 2007 PRINCE OF WALES 3403 ANON New Steam for the Main Line Building Britain’s Most Powerful Steam Locomotive Recreating Gresley’s last design THE COMMUNICATION CORD No. 61 Spring 2021 Simon Apsley/Frewer & Co. Engineers A superb rendering by Simon Apsley of the 3D CAD of Prince of Wales's front end, cut away to show the Lentz gearbox and the double Kylchap exhaust in the smokebox. POETRY IN MOTION? by Graham Langer Despite the difficulties of the past year has involved Frewer and Co. Engineers of No. 2007 – in consequence he has the P2 project continues to forge ahead undertaking the Computational Fluid been sending us the most impressive and we have reached the stage of fine- Dynamics [CFD] analysis of the cylinder renderings of parts and sections of tuning the design for the cylinders and block steam passageways and one of the new P2, some of which we are valve gear so that construction can be their team, Simon Apsley, has got a delighted to feature in this edition of The put out to tender. Part of the process bit carried away with the 3D CADs Communication Cord. TCC 1 CONTENTS EDITORIAL by Graham Langer FROM THE CHAIR by Steve Davies PAGE 1 Poetry in motion? As I write this towards the use of coal. However, the n recent weeks time, from Leicester to Carlisle via the physically meeting. Video conferencing is PAGE 2 editorial Tornado sector produces a tiny percentage of we have all felt spectacular Settle & Carlisle Railway. It probably here to stay but punctuated by Contents is still “confined to the country’s greenhouse gasses and Idrawn even might seem premature to say this, but I periodic ‘actual’ meetings. -

Interurban Bus | Time to Raise the Profile V 1.0 | Introduction

Interurban Bus Time to raise the profile March 2018 Contents Acknowledgements Foreword 1.0 Introduction . 1 2.0 The evolution of Interurban Bus services . 3 3.0 Single route Interurban services (case studies) . 19 4.0 Interurban Bus networks . 35 5.0 Future development: digital and related technologies . 65 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations. 79 Annex A: TrawsCymru network development history and prospects. .A1 Annex B: The development history of Fife’s Express City Connect interurban bus network . A4 Annex C: Short history of Lincolnshire's interurban bus network . A6 www.greengauge21.net © March 2018, Greengauge 21, Some Rights Reserved: We actively encourage people to use our work, and simply request that the use of any of our material is credited to Greengauge 21 in the following way: Greengauge 21, Title, Date Acknowledgements Foreword The authors (Dylan Luke, Jim Steer and Professor Peter White) are grateful to members of the The importance of connectivity in shaping local economic prosperity is much discussed, both in Omnibus Society, who facilitated researching historic records at its Walsall Library. terms of digital (broadband speeds) and personal travel – for instance to access job markets or to reach increasingly ‘regionalised’ key services. Today’s policy makers are even considering re-opening We are also grateful to a number of individuals and organisations whose kind assistance has long closed branch railways to reach places that seem remote or cut off from jobs and opportunity. been very useful in compiling this report. Particular thanks go to David Hall (Network Manager) in respect of the TrawsCymru case study; Sarah Elliott (Marketing Manager) of Stagecoach East Here we examine a mode of transport that is little understood and often over-looked.