Archaeology in Hampshire for 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NOTICE of POLL Notice Is Hereby Given That

HAMPSHIRE COUNTY COUNCIL Election of County Councillor for the YATELEY EAST, BLACKWATER & ANCELLS Division NOTICE OF POLL Notice is hereby given that: 1. A poll will be held on Thursday, 2nd May 2013 between 7am and 10pm. 2. Number of councillors to be elected is ONE. 3. The following people stand nominated: SURNAME OTHER ADDRESS OF DESCRIPTION (if NAMES OF ASSENTERS TO THE NOMINATION NAMES CANDIDATE any) (PROPOSER (P) AND SECONDER (S) LISTED FIRST) Collett Adrian 47 Globe Farm Lane, Liberal Democrat DAVID E SIMPSON(P), DAVID J MURR(S), JOHN W Darby Green, Blackwater, KEANE, GILLIAN E A HENNELL, ROBERT E HARWARD, Hampshire, GU17 0DY STUART G BAILEY, BRIAN F BLEWETT, COLIN IVE, MARGUERITE SIMPSON, ELOISE C ESLAMI Dickens Shawn Meadowcroft, Chequers Conservative Party EDWARD N BROMHEAD(P), STEPHEN A GORYS(S), Lane, Eversley, Hampshire, Candidate JULIET M BOWELL, FREDERICK G BAGGS, RG27 0NY CHRISTOPHER W PHILLIPS-HART, SHANE P M MASON, EMMA MASON, SUSAN H LINDEQUE, COURTNEY-TYLA LINDEQUE, PAMELA M MEDLEY Lawrie Les 106 Kingsway, Blackwater, Labour and Co- PATRICIA D DOWDEN(P), KEITH CARTWRIGHT(S), Hants, GU17 0JD operative Party NICHOLAS C J KAY, HARRY A R HAMBLIN, MAUREEN D Candidate HAMBLIN, CHARLES E LINGS, MICHAEL T STEWART, ISMAIL KESENCI, SYLVIA M RHODES, KENNETH B RHODES Tennison Stanley John 51 Stratfield Road, UKIP KAREN RICHMOND(P), EMMA RICHMOND(S), Basingstoke, RG21 5RS DOUGLAS J ATTWELL, KEITH E SANTON, RALPH D CANNON, BRIAN J BISHOP, ROYSTON F PACKMAN, ANTHONY J F HOCKING, KATHLEEN AUSTIN, STEPHEN M WINTERBURN Situation of -

A 10 Mile Walk Between the Ship and Bell in Horndean Village and The

The Trail The Ship and Bell A charming 17th century This walk is suitable for reasonably fit and able walkers. The inn offering stylish distance is 10 miles or 16 kms, with a total ascent of 886 feet or accommodation, good food, 270 metres. Ordnance Survey Explorer 120 Chichester map covers Fuller’s award winning this area. We recommend you take a map with you. beers and a warm welcome. 6 London Road, Horndean, Waterlooville, Hampshire PO8 0BZ Tel: 023 9259 2107 Email: [email protected] The Hampshire Hog The Red Lion The Hampshire Hog Overlooking the South Downs, this beautifully re- furbished inn is the perfect place to base yourself for The Ship business or leisure. and Bell London Road, Clanfield, Waterlooville, Hampshire PO8 0QD FREE PINT OF DISCOVERY BLONDE BEER Tel: 023 9259 1083 to everyone who completes the trail* Email: [email protected] What better way to reward yourself after a long walk than with a refreshing pint of Discovery Blonde Beer. Discovery The Red Lion is a delicious chilled cask beer, exclusive to Fuller’s pubs. Here’s how to claim your free pint: A picturesque country pub 1) Buy any drink (including soft drinks) from two of the dating back to the 12th pubs on this trail and receive a Fuller’s stamp from century serving excellent each pub on your Walk and Cycle trail leaflet. food, all freshly prepared 2) Present your stamped leaflet at the third and final using locally sourced pub you visit along the trail and you will receive a produce. -

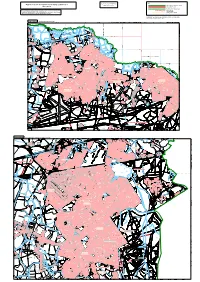

Map Referred to in the Hart

KEY Map referred to in the Hart (Electoral Changes) Order 2012 Scale : 1cm = 0.08500 km Grid interval 1km DISTRICT COUNCIL BOUNDARY Sheet 2 of 2 WARD BOUNDARY PARISH BOUNDARY PARISH WARD BOUNDARY This map is based upon Ordnance Survey material with the permission of Ordnance Survey on behalf of FLEET WEST WARD WARD NAME the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office © Crown copyright. FLEET CP PARISH NAME Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution or civil proceedings. FROGMORE PARISH WARD PARISH WARD NAME The Local Government Boundary Commission for England GD100049926 2012. COINCIDENT BOUNDARIES ARE SHOWN AS THIN COLOURED LINES SUPERIMPOSED OVER WIDER ONES. SHEET 2, MAP 2A Ward boundaries in Yateley town L O Sand and Gravel Pit N G W A T E R R D Playing Field E N A L Golf Course L L I B M 3 0 Playing Field 16 Cricket Ground Y WA L'S HAL E AN S L ER DL AN CH C F O O P X B S 3 L E 2 A 7 N L RNE 6 2 RYE E A WEST F 1 N 0 M M E 3 A I L Y Eversley B L F L L A O Cross N W E E STABL R M E VIEW D O The Yateley Lakes R U E L N S A H L A S NS M D R FO G L E X A L DR Y N D B N E M E A S E V H I A O C N R R R A D S C L F CR Y H O R FT N E LAN A Y E E ' L G W S L A A E L N EVERSLEY RD G R A G R E A S A I A C L F I L E N V I V N D A L H L U IL R R VI M S E T ADIN CA G R OAD RA R G D E E R N D A Yateley L E e Industries V n WEY a T BR Up Green O IDG L Yateley Green E H M L EAD n E OAD e R ING L D e REA r I N G K E B N A St Peter's D 3 L A 0 Church N O 1 R E Yateley 6 A B E K K C Manor School Y D F I L A IR G -

The Idsworth Church Friends Trust 3 AGM – Wednesday 24 April, 2019

The Idsworth Church Friends Trust 3rd AGM – Wednesday 24th April, 2019 1.Apologies: Dinah Lawson, Jennifer Oatley, Rebecca Probert, Deborah Richards, June Heap, Jill Everett, Tom Everett, Mike Driver, David Uren, Cllr Chris Stanley, Cllr Marge Harvey, Alan Hakim. Attendance: 35 Confirm Minutes of the last meeting (19th April, 2018): These were made available to all Friends via the website. Proposer: Andrew Fisk and Seconder: Simon Hartley 2. Chairman’s Review of the Year: ‘It is incredible to think that, a year ago, we were sitting in the church on the new pew cushions purchased by The Friends and, I am pleased to say, they have proved to make life very much more comfortable for those attending church services, concerts, social events and even AGMs! In April, 2018, Mr Tobit Curteis of the Courthauld Institute was commissioned to inspect the church environment and advise on the condition of the wall paintings. His report was subsequently included in the application to the Heritage Lottery Fund. The last twelve months has been a very busy time for the Friends’ Trust. So what have we achieved during the course of the last year? Well, ten events took place in 2018 for a start: Despite a very hot summer, the weather deluged for our Dark Skies Event in April and we were confined to activities in the church – a great pity as we had a number of families attending and, supported by the team of experts from Clanfield observatory, there was no opportunity to star gaze through their telescopes due to the heavy rain. -

Landowner Deposits Register

Register of Landowner Deposits under Highways Act 1980 and Commons Act 2006 The first part of this register contains entries for all CA16 combined deposits received since 1st October 2013, and these all have scanned copies of the deposits attached. The second part of the register lists entries for deposits made before 1st October 2013, all made under section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980. There are a large number of these, and the only details given here currently are the name of the land, the parish and the date of the deposit. We will be adding fuller details and scanned documents to these entries over time. List of deposits made - last update 12 January 2017 CA16 Combined Deposits Deposit Reference: 44 - Land at Froyle (The Mrs Bootle-Wilbrahams Will Trust) Link to Documents: http://documents.hants.gov.uk/countryside/Deposit44-Bootle-WilbrahamsTrustLand-Froyle-Scan.pdf Details of Depositor Details of Land Crispin Mahony of Savills on behalf of The Parish: Froyle Mrs Bootle-WilbrahamWill Trust, c/o Savills (UK) Froyle Jewry Chambers,44 Jewry Street, Winchester Alton Hampshire Hampshire SO23 8RW GU34 4DD Date of Statement: 14/11/2016 Grid Reference: 733.416 Deposit Reference: 98 - Tower Hill, Dummer Link to Documents: http://documents.hants.gov.uk/rightsofway/Deposit98-LandatTowerHill-Dummer-Scan.pdf Details of Depositor Details of Land Jamie Adams & Madeline Hutton Parish: Dummer 65 Elm Bank Gardens, Up Street Barnes, Dummer London Basingstoke SW13 0NX RG25 2AL Date of Statement: 27/08/2014 Grid Reference: 583. 458 Deposit Reference: -

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation Sincs Hampshire.Pdf

Sites of Importance for Nature Conservation (SINCs) within Hampshire © Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre No part of this documentHBIC may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recoding or otherwise without the prior permission of the Hampshire Biodiversity Information Centre Central Grid SINC Ref District SINC Name Ref. SINC Criteria Area (ha) BD0001 Basingstoke & Deane Straits Copse, St. Mary Bourne SU38905040 1A 2.14 BD0002 Basingstoke & Deane Lee's Wood SU39005080 1A 1.99 BD0003 Basingstoke & Deane Great Wallop Hill Copse SU39005200 1A/1B 21.07 BD0004 Basingstoke & Deane Hackwood Copse SU39504950 1A 11.74 BD0005 Basingstoke & Deane Stokehill Farm Down SU39605130 2A 4.02 BD0006 Basingstoke & Deane Juniper Rough SU39605289 2D 1.16 BD0007 Basingstoke & Deane Leafy Grove Copse SU39685080 1A 1.83 BD0008 Basingstoke & Deane Trinley Wood SU39804900 1A 6.58 BD0009 Basingstoke & Deane East Woodhay Down SU39806040 2A 29.57 BD0010 Basingstoke & Deane Ten Acre Brow (East) SU39965580 1A 0.55 BD0011 Basingstoke & Deane Berries Copse SU40106240 1A 2.93 BD0012 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood North SU40305590 1A 3.63 BD0013 Basingstoke & Deane The Oaks Grassland SU40405920 2A 1.12 BD0014 Basingstoke & Deane Sidley Wood South SU40505520 1B 1.87 BD0015 Basingstoke & Deane West Of Codley Copse SU40505680 2D/6A 0.68 BD0016 Basingstoke & Deane Hitchen Copse SU40505850 1A 13.91 BD0017 Basingstoke & Deane Pilot Hill: Field To The South-East SU40505900 2A/6A 4.62 -

Sydenhams Football League News 2019/20 Edition Number 50

SYDENHAMS FOOTBALL LEAGUE NEWS 2019/20 EDITION NUMBER 50 Hello and welcome to the latest edition of your Newsletter, if you have anything to contribute, please do get in touch by email- [email protected] You can keep up to date with all the news from around the League by following us on Twitter at - @Sydwessex You are more than welcome to use any material (excluding attributed photographs) but it would be appreciated if any material used is acknowledged. It is hoped you enjoy reading this each week. With readership quite widespread, not only within our own competition, but across the three counties and beyond- if ANY club has anything they’d like to have published in here, whether that be a request for helpers, promotion of forthcoming events, items required or available for sale please contact the Newsletter Editor. As a general reminder- Match Reports, player news and photos are always welcome- it is your Newsletter! JOINT PRESS RELEASE SYDENHAMS LTD STATEMENT It has been a privilege for Sydenhams to have worked with the Wessex league over the past 17 years but we have now taken the difficult decision that 2020/21 will be our last season as sponsor. The league has meant a huge amount to us all at Sydenhams and we would like to take this opportunity to applaud the exceptional work of the Wessex league and everyone associated with it, we are truly honoured to have been part of something so special for nearly two decades and wish you all the very best success for future. -

Stop Message Magazine Issue 19 – April 2016

Issue 19 - April 2016 STOP MESSAGE The magazine of the Hampshire Fire and Rescue Service Past Members Association www.xhfrs.org.uk Make Pumps 10, HMS Collingwood 15 October 1976 Inside... SPECIAL BUMPERGuess who becameEDITION! a trucker? EATING IN THE FIFTIES Oil was for lubricating, fat was for cooking. Tea was made in a teapot using tea leaves and never green. Sugar enjoyed a good press in those days, and was regarded as being white gold. Cubed sugar was regarded as posh. Fish didn’t have fingers in those days. Eating raw fish was called poverty, not sushi. None of us had ever heard of yoghurt. Healthy food consisted of anything edible. People who didn’t peel potatoes were regarded as lazy. Pasta was not eaten in New Zealand. Indian restaurants were only found in India. Curry was a surname. Cooking outside was called camping. A takeaway was a mathematical problem. Seaweed was not a recognised food. A pizza was something to do with a leaning “Kebab” was not even a word, never mind a tower. food. All potato chips were plain; the only choice we Prunes were medicinal. had was whether to put the salt on or not. Surprisingly, muesli was readily available, it Rice was only eaten as a milk pudding. was called cattle feed. Calamari was called squid and we used it as Water came out of the tap. If someone had fish bait. suggested bottling it and charging more than petrol for it , they would have become a A Big Mac was what we wore when it was laughing stock!! raining. -

Chalton Chalton

Chalton Chalton 1.0 PARISH Clanfield & Rowlands Castle parishes, formerly a separate parish. 2.0 HUNDRED Finchdean 3.0 NGR 473200 116000 4.0 GEOLOGY Upper Chalk 5.0 SITE CONTEXT (Map 2) Chalton is a valley settlement at 95m AOD. However, the terrain rises sharply to the south (Chalton Down, 144m AOD) and to the east. Windmill Hill is 1km west whilst to the north there is a more gentle climb on to the lower slopes of Holt Down (Queen Elizabeth Country Park). Chalton is arranged around a cross-roads and these provide access to the Downs. The south / north route is South Lane below the cross-roads, North Lane above. North Lane is little more than a track, whilst the road west / east (Chalton Lane, formerly Wicker Lane) is a link to the A3 (T). There has been much rebuilding in Chalton during the C20 and agricultural activity is intensive in an area that is rich in archaeology both in the valley and on the Downs. Chalton and Clanfield parishes were amalgamated in 1932 6.0 PLAN TYPE & DESCRIPTION (Maps 3, 4 & 5) Church & manor house + irregular agglomeration 6.1 Church & manor house The core of the settlement is the C12 parish church and the adjacent building south-west of the church that is now known as The Priory. This latter building was formerly the rectory but upon cessation of this function it was re- named as The Priory in the C20. This is appropriate because the building is C14, C15 in date and is almost certainly associated with the Priory of Nuneaton which held the advowson of Chalton from 1154. -

Parents' Bulletin

Headteacher: Mr M F Jackman MA NPQH YATELEY SCHOOL Telephone: 01252 879222 Facsimile: 01252 872517 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.yateley.hants.sch.uk School Lane, Yateley, Hampshire, GU46 6NW MFJ/BLE A PERFORMING ARTS COLLEGE 14th June 2017 Issue No. 33 Parents’ Bulletin Dear Parents Random Acts of Kindness – RAK We had a working party of pastoral leaders and colleagues thinking of ways to recognise and encourage the positive behaviours that our students so regularly show. All staff have been issued with slips to give to students when they see them being kind to each other, picking up litter, opening doors, in general acting thoughtfully. Students then take this named slip to the House Centre and get entered into a raffle for a number of prizes at the end of term. This initiative will run for a period of time and we will revisit it in future. So far the response has been excellent – some students have even set up elaborate “falling over and helping up” routines, which adds to the humour but doesn’t get a slip. GCSE Examinations These continue until Wednesday 21st June so there is one more week to go. The response from students has been excellent. Only on Tuesday morning around 100 students turned up for the Maths exam breakfast to “wake up their Maths brain” before the final Maths exam. Our students have worked hard for their exams and our Maths colleagues too, to provide the support that will guarantee their success. There has been one disappointment – a student who had their mobile phone on them in the exam. -

Winchester Museums Service Historic Resources Centre

GB 1869 AA2/110 Winchester Museums Service Historic Resources Centre This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 41727 The National Archives ppl-6 of the following report is a list of the archaeological sites in Hampshire which John Peere Williams-Freeman helped to excavate. There are notes, correspondence and plans relating to each site. p7 summarises Williams-Freeman's other papers held by the Winchester Museums Service. William Freeman Index of Archaeology in Hampshire. Abbots Ann, Roman Villa, Hampshire 23 SW Aldershot, Earthwork - Bats Hogsty, Hampshire 20 SE Aldershot, Iron Age Hill Fort - Ceasar's Camp, Hampshire 20 SE Alton, Underground Passage' - Theddon Grange, Hampshire 35 NW Alverstoke, Mound Cemetery etc, Hampshire 83 SW Ampfield, Misc finds, Hampshire 49 SW Ampress,Promy fort, Hampshire 80 SW Andover, Iron Age Hill Fort - Bagsbury or Balksbury, Hampshire 23 SE Andover, Skeleton, Hampshire 24 NW Andover, Dug-out canoe or trough, Hampshire 22 NE Appleshaw, Flint implement from gravel pit, Hampshire 15 SW Ashley, Ring-motte and Castle, Hampshire 40 SW Ashley, Earthwork, Roman Building etc, Hampshire 40 SW Avington, Cross-dyke and 'Ring' - Chesford Head, Hampshire 50 NE Barton Stacey, Linear Earthwork - The Andyke, Hampshire 24 SE Basing, Park Pale - Pyotts Hill, Hampshire 19 SW Basing, Motte and Bailey - Oliver's Battery, Hampshire 19 NW Bitterne (Clausentum), Roman site, Hampshire 65 NE Basing, Motte and Bailey, Hampshire 19 NW Basingstoke, Iron -

PARISH PROFILE for the United Benefice of Blendworth, Holy Trinity with Chalton, St

PARISH PROFILE For The United Benefice of Blendworth, Holy Trinity with Chalton, St. Michael and Idsworth, St. Hubert April 2019 A Mission Opportunity Awaiting YOUR call Parish Profile for United Benefice 1 Contents About Us Page 3 Aspirations Page 4 Location Page 5 Benefice Wide Activities Page 6 Services Page 9 Holy Trinity Blendworth Page 11 St Michael and All Angels Chalton Page 13 St Hubert Idsworth Page 15 St John’s Rectory Page 17 Blendworth House for Duty Page 18 Working Together Page 19 Your Personal Development Page 21 Parish Profile for United Benefice 2 About Us The United Benefice of Holy Trinity Blendworth with St. Michael's Chalton with St. Hubert's Idsworth Web site: www.bcichurches.org.uk e-mail: [email protected] Facebook: Holy Trinity Blendworth Office Telephone (023) 9259 7023 The three parishes are set in an area of outstanding natural beauty with congregations drawn from rural and semi-rural areas, although Blendworth's makeup is predominantly suburban. Our churches draw their congregations mainly from outside of their catchment areas. At end of March 2019 there were a total of 197 persons on the electoral rolls of the benefice (Holy Trinity 102, St. Hubert 51, and St. Michael 44). The average congregations attending church is: Holy Trinity 54 + 8 children, St. Hubert 24+2 children and St. Michael 12. Considered to be quite ‘middle-of-the-road Anglican’ in our worship, we have seen growth and change and a pattern of joint services in recent times with our own united benefice communion services shared around our three churches.