The Inns of Rowlands Castle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chart Book Template

Real Chart Page 1 become a problem, since each track can sometimes be released as a separate download. CHART LOG - F However if it is known that a track is being released on 'hard copy' as a AA side, then the tracks will be grouped as one, or as soon as known. Symbol Explanations s j For the above reasons many remixed songs are listed as re-entries, however if the title is Top Ten Hit Number One hit. altered to reflect the remix it will be listed as would a new song by the act. This does not apply ± Indicates that the record probably sold more than 250K. Only used on unsorted charts. to records still in the chart and the sales of the mix would be added to the track in the chart. Unsorted chart hits will have no position, but if they are black in colour than the record made the Real Chart. Green coloured records might not This may push singles back up the chart or keep them around for longer, nevertheless the have made the Real Chart. The same applies to the red coulered hits, these are known to have made the USA charts, so could have been chart is a sales chart and NOT a popularity chart on people’s favourite songs or acts. Due to released in the UK, or imported here. encryption decoding errors some artists/titles may be spelt wrong, I apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. The chart statistics were compiled only from sales of SINGLES each week. Not only that but Date of Entry every single sale no matter where it occurred! Format rules, used by other charts, where unnecessary and therefore ignored, so you will see EP’s that charted and other strange The Charts were produced on a Sunday and the sales were from the previous seven days, with records selling more than other charts. -

A 10 Mile Walk Between the Ship and Bell in Horndean Village and The

The Trail The Ship and Bell A charming 17th century This walk is suitable for reasonably fit and able walkers. The inn offering stylish distance is 10 miles or 16 kms, with a total ascent of 886 feet or accommodation, good food, 270 metres. Ordnance Survey Explorer 120 Chichester map covers Fuller’s award winning this area. We recommend you take a map with you. beers and a warm welcome. 6 London Road, Horndean, Waterlooville, Hampshire PO8 0BZ Tel: 023 9259 2107 Email: [email protected] The Hampshire Hog The Red Lion The Hampshire Hog Overlooking the South Downs, this beautifully re- furbished inn is the perfect place to base yourself for The Ship business or leisure. and Bell London Road, Clanfield, Waterlooville, Hampshire PO8 0QD FREE PINT OF DISCOVERY BLONDE BEER Tel: 023 9259 1083 to everyone who completes the trail* Email: [email protected] What better way to reward yourself after a long walk than with a refreshing pint of Discovery Blonde Beer. Discovery The Red Lion is a delicious chilled cask beer, exclusive to Fuller’s pubs. Here’s how to claim your free pint: A picturesque country pub 1) Buy any drink (including soft drinks) from two of the dating back to the 12th pubs on this trail and receive a Fuller’s stamp from century serving excellent each pub on your Walk and Cycle trail leaflet. food, all freshly prepared 2) Present your stamped leaflet at the third and final using locally sourced pub you visit along the trail and you will receive a produce. -

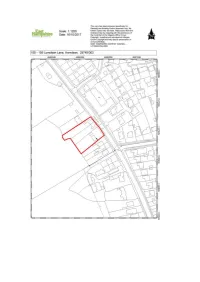

EHDC Part 1 Section 1 Item 2 155 Lovedean Lane.Pdf

Item No.: 2 The information, recommendations, and advice contained in this report are correct as at the date of preparation, which is more than one week in advance of the Committee meeting. Because of the time constraints some reports may have been prepared in advance of the final date given for consultee responses or neighbour comments. Any changes or necessary updates to the report will be made orally at the Committee meeting. PROPOSAL 5 dwellings following demolition of existing dwelling (as amended by plans received 28 June 2017) LOCATION: 155 - 159 Lovedean Lane, Horndean, Waterlooville, PO8 9RW REFERENCE 29745/002 PARISH:Horndean APPLICANT: Capital Homes (Southern) Ltd CONSULTATION EXPIRY 20 July 2017 APPLICATION EXPIRY : 29 December 2016 COUNCILLOR: Cllr S E Schillemore SUMMARY RECOMMENDATION: PERMISSION The application is presented to the Planning Committee at the discretion of the Head of Planning. Site and Development The site lies on the western side of Lovedean Lane, within the settlement policy boundary of Horndean. The site comprises a derelict farmhouse dating to the early twentieth century and a pair of semi-detached Victorian cottages, also currently un-occupied. The area of land to the rear of the buildings comprises cleared scrub and beyond the site to the west, open countryside rises above the level of Lovedean Lane. Development on the western side of Lovedean Lane in the vicinity of the site generally follows a linear pattern, but there is some development in depth at Old Barn Gardens, approximately 120m to the south and there is also development in depth at James Copse Road and Ashley Close to the south and to the north, approximately 50m away. -

Notification of All Planning Decisions Issued for the Period 11 June 2021 to 17 June 2021

NOTIFICATION OF ALL PLANNING DECISIONS ISSUED FOR THE PERIOD 11 JUNE 2021 TO 17 JUNE 2021 Reference No: 26982/011 PARISH: Horndean Location: Yew Tree Cottage, Eastland Gate, Lovedean, Waterlooville, PO8 0SR Proposal: Installation of access gates with brick piers, resurfacing of hardstanding and installation of training mirrors along east side of manege (land adj to Yew Tree Cottage) Decision: REFUSAL Decision Date: 16 June, 2021 Reference No: 59273 PARISH: Horndean Location: 31 Merchistoun Road, Horndean, Waterlooville, PO8 9NA Proposal: Prior notification for single storey development extending 4 metres beyond the rear wall of the original dwelling, incorporating an eaves height of 3 metres and a maximum height of 3 metres Decision: Gen Permitted Development Conditional Decision Date: 17 June, 2021 Reference No: 37123/005 PARISH: Horndean Location: Church House, 329 Catherington Lane, Horndean Waterlooville PO8 0TE Proposal: Change of use of existing outbuilding to holiday let and associated works (as amended by plans received 20 May 2021). Decision: PERMISSION Decision Date: 11 June, 2021 Reference No: 50186/002 PARISH: Horndean Location: 38 London Road, Horndean, Waterlooville, PO8 0BX Proposal: Retrospective application for entrance gates and intercom Decision: REFUSAL Decision Date: 15 June, 2021 Reference No: 59252 PARISH: Rowlands Castle Location: 18 Nightingale Close, Rowlands Castle, PO9 6EU Proposal: T1-Oak-Crown height reduction by 3m, leaving a crown height of 13m. Crown width reduction by 2.5m, leaving a crown width of 4.5m. Decision: CONSENT Decision Date: 17 June, 2021 Reference No: 25611/005 PARISH: Rowlands Castle Location: 5 Wellswood Gardens, Rowlands Castle, PO9 6DN Proposal: First floor side extension over garage, replacement of bay window with door and internal works. -

The Idsworth Church Friends Trust 3 AGM – Wednesday 24 April, 2019

The Idsworth Church Friends Trust 3rd AGM – Wednesday 24th April, 2019 1.Apologies: Dinah Lawson, Jennifer Oatley, Rebecca Probert, Deborah Richards, June Heap, Jill Everett, Tom Everett, Mike Driver, David Uren, Cllr Chris Stanley, Cllr Marge Harvey, Alan Hakim. Attendance: 35 Confirm Minutes of the last meeting (19th April, 2018): These were made available to all Friends via the website. Proposer: Andrew Fisk and Seconder: Simon Hartley 2. Chairman’s Review of the Year: ‘It is incredible to think that, a year ago, we were sitting in the church on the new pew cushions purchased by The Friends and, I am pleased to say, they have proved to make life very much more comfortable for those attending church services, concerts, social events and even AGMs! In April, 2018, Mr Tobit Curteis of the Courthauld Institute was commissioned to inspect the church environment and advise on the condition of the wall paintings. His report was subsequently included in the application to the Heritage Lottery Fund. The last twelve months has been a very busy time for the Friends’ Trust. So what have we achieved during the course of the last year? Well, ten events took place in 2018 for a start: Despite a very hot summer, the weather deluged for our Dark Skies Event in April and we were confined to activities in the church – a great pity as we had a number of families attending and, supported by the team of experts from Clanfield observatory, there was no opportunity to star gaze through their telescopes due to the heavy rain. -

Landowner Deposits Register

Register of Landowner Deposits under Highways Act 1980 and Commons Act 2006 The first part of this register contains entries for all CA16 combined deposits received since 1st October 2013, and these all have scanned copies of the deposits attached. The second part of the register lists entries for deposits made before 1st October 2013, all made under section 31(6) of the Highways Act 1980. There are a large number of these, and the only details given here currently are the name of the land, the parish and the date of the deposit. We will be adding fuller details and scanned documents to these entries over time. List of deposits made - last update 12 January 2017 CA16 Combined Deposits Deposit Reference: 44 - Land at Froyle (The Mrs Bootle-Wilbrahams Will Trust) Link to Documents: http://documents.hants.gov.uk/countryside/Deposit44-Bootle-WilbrahamsTrustLand-Froyle-Scan.pdf Details of Depositor Details of Land Crispin Mahony of Savills on behalf of The Parish: Froyle Mrs Bootle-WilbrahamWill Trust, c/o Savills (UK) Froyle Jewry Chambers,44 Jewry Street, Winchester Alton Hampshire Hampshire SO23 8RW GU34 4DD Date of Statement: 14/11/2016 Grid Reference: 733.416 Deposit Reference: 98 - Tower Hill, Dummer Link to Documents: http://documents.hants.gov.uk/rightsofway/Deposit98-LandatTowerHill-Dummer-Scan.pdf Details of Depositor Details of Land Jamie Adams & Madeline Hutton Parish: Dummer 65 Elm Bank Gardens, Up Street Barnes, Dummer London Basingstoke SW13 0NX RG25 2AL Date of Statement: 27/08/2014 Grid Reference: 583. 458 Deposit Reference: -

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" Vinyl Single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE in the MOVIES Dr

1978-05-22 P MACHO MAN Village People RCA 7" vinyl single 103106 1978-05-22 P MORE LIKE IN THE MOVIES Dr. Hook EMI 7" vinyl single CP 11706 1978-05-22 P COUNT ON ME Jefferson Starship RCA 7" vinyl single 103070 1978-05-22 P THE STRANGER Billy Joel CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222406 1978-05-22 P YANKEE DOODLE DANDY Paul Jabara AST 7" vinyl single NB 005 1978-05-22 P BABY HOLD ON Eddie Money CBS 7" vinyl single BA 222383 1978-05-22 P RIVERS OF BABYLON Boney M WEA 7" vinyl single 45-1872 1978-05-22 P WEREWOLVES OF LONDON Warren Zevon WEA 7" vinyl single E 45472 1978-05-22 P BAT OUT OF HELL Meat Loaf CBS 7" vinyl single ES 280 1978-05-22 P THIS TIME I'M IN IT FOR LOVE Player POL 7" vinyl single 6078 902 1978-05-22 P TWO DOORS DOWN Dolly Parton RCA 7" vinyl single 103100 1978-05-22 P MR. BLUE SKY Electric Light Orchestra (ELO) FES 7" vinyl single K 7039 1978-05-22 P HEY LORD, DON'T ASK ME QUESTIONS Graham Parker & the Rumour POL 7" vinyl single 6059 199 1978-05-22 P DUST IN THE WIND Kansas CBS 7" vinyl single ES 278 1978-05-22 P SORRY, I'M A LADY Baccara RCA 7" vinyl single 102991 1978-05-22 P WORDS ARE NOT ENOUGH Jon English POL 7" vinyl single 2079 121 1978-05-22 P I WAS ONLY JOKING Rod Stewart WEA 7" vinyl single WB 6865 1978-05-22 P MATCHSTALK MEN AND MATCHTALK CATS AND DOGS Brian and Michael AST 7" vinyl single AP 1961 1978-05-22 P IT'S SO EASY Linda Ronstadt WEA 7" vinyl single EF 90042 1978-05-22 P HERE AM I Bonnie Tyler RCA 7" vinyl single 1031126 1978-05-22 P IMAGINATION Marcia Hines POL 7" vinyl single MS 513 1978-05-29 P BBBBBBBBBBBBBOOGIE -

The Making of Havant 2

The Making of Havant St Faith’s Church and West Street circa 1910. Volume 2 of 5 Havant History Booklet No. 41 View all booklets, comment, and order on line at hhbkt.com £5 The Roman Catholic Church and Presbetery in West Street. The wedding of Canon Scott’s daughter was a great attraction. 2 Contents The Churches of Havant – Ian Watson 5 St Faith’s Church 5 The Reverend Canon Samuel Gilbert Scott 11 John Julius Angerstein 13 The Bells of St Faith’s Church 13 The Roman Catholic Church – Christine Houseley 16 The Methodists 19 The Reverend George Standing 22 Dissenters 26 Lieutenant General Sir Frederick Fitzwygram 31 Havant’s Bricks – Their Time and Place – Ian Watson 37 Local Volunteers and Territorials 49 Law and Order – Pat Dann 61 The Agricultural Uprising 69 Education 71 Private Schools 78 Most of the articles contained in these five The Making of Havant booklets are the original work of the Havant Local History Group, which were written in the late 1970s. They have been edited by Ralph Cousins and John Pile and have only been amended where further information has become available or where landmark locations have changed. Our grateful thanks should be extended to the members of the group for their hard work in putting together this reminder of Havant’s past history. Ralph Cousins – August 2014 023 9248 4024 [email protected] 3 Overhaul of the bells at St Faith’s Church in 1973. This bell weighs 15½ cwt (800kg). From the right Michael Johnson and Morgan Marshall. -

Neighbourhood Plan

Appendix to Rowlands Castle Parish Council’s response to the Further Limited Draft Consultation on LGBCE’s Review of East Hampshire District Council Table of Contents 1.0 Consultation on LGBCE’s draft recommendations in 2017 ......................................... 2 1.1 Residents ............................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Political Parties .................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Councillors .......................................................................................................................... 2 1.4 Parish and Town Councils ................................................................................................... 2 1.5 Hampshire County Council ................................................................................................. 2 2.0 Rowlands Castle Vision .................................................................................................... 3 3.0 Rowlands Castle Neighbourhood Plan ............................................................................ 3 4.0 Rowlands Castle Community Organisations .................................................................. 3 4.1 Rowlands Castle Parish Council ......................................................................................... 3 4.2 Rowlands Castle Association ............................................................................................. -

The Postal History of Waterlooville Including Cosham, Widley, Purbrook, Denmead, Hambledon, Cowplain, Lovedean, Horndean and Chalton

The Postal History of Waterlooville including Cosham, Widley, Purbrook, Denmead, Hambledon, Cowplain, Lovedean, Horndean and Chalton by Mike Hill July 2015 £5 Tourist Map of 1991 showing the locations of Post Offices in the Waterlooville area. 2 Havant Borough History Booklet No. 52 To view, comment, and order all booklets visit: www.hhbkt.com Read also Booklet No. 38: A History of the Post Office in the Havant Area Edited by Ralph Cousins 3 4 The Postal History of Waterlooville including Cosham, Widley, Purbrook, Denmead, Hambledon, Cowplain, Lovedean, Horndean and Chalton Mike Hill Introduction The Waterlooville Philatelic Society was formed at the time of the great stamp collecting boom of the early 1970s and as a founder member I discovered that there was little information about the postal history of the local area since the founding of the village in 1815 some 200 years ago. Thus I was encouraged to start out on a journey of exploration into the history of postal services in the local area, a journey which has given me many hours of enjoyment. What I have achieved has been helped enormously by those of the Waterlooville Philatelic Society notably the late Eric Whyley and Mike English, and also the late Geoffrey Salter of the Waterlooville Library. Much of my research was published in the Journal of the Hampshire Postal History Society of which I was editor for a number of years. I must also thank David Coxon whose father took over from George Pook as postmaster in the early fifties for his memories and Paul Costen [www.costen.co.uk] who allowed me access to his scanned collection of postcards to search for Post Offices. -

Pearsons Property Auction Wednesday 1 October 2014

Pearsons Property Auction Wednesday 1 October 2014 Commencing at 11am in the Hambledon Suite The Solent Hotel, Whiteley, Fareham, PO15 7AJ (just off junction 9 of the M27) Part of the national Auction House network Pearsons Property Auctions in association with Auction House Local KnowleDGE – NatIonal StrenGth We offer a comprehensive service to clients wishing to offer their property for sale by Public Auction. Auction House is the fastest growing auctioneering network in the UK and an increasingly attractive alternative to major London players and corporate firms. Now operating from 30 regional auction rooms with others set to open shortly, Auction House is the most effective independent option to local sellers, and operates from auction rooms easily accessible to local buyers. Regional Auction House’s are run by prominent Estate Agents and experienced Auctioneers who have a wealth of knowledge and market experience. Auction House Pearsons offers that local capability and expertise along with national advertising and marketing – a combination of local knowledge and national strength that is both successful and compelling. Instructions are invited for our next Property Auction To be held on Wednesday 10th December 2014 at 11am at The Solent Hotel, Whiteley, Fareham, PO15 7AJ Contact auctioneer Toby Wheatley for a free consultation. 023 8047 4274 pearsonsauctions.com Pearsons Property Auction Wednesday 1 October 2014 Pearsons Property Auctions in association with Auction House Contents Local KnowleDGE – NatIonal StrenGth 04 Important -

HAMPSHIRE. [ KELLY's

116 C.ATHERINGTON. HAMPSHIRE. [ KELLY's (afterwards James IT.) with Anne Hyde took placa 3 Catherington Rural District Council. Sept. r66o, although other authorities give Worcester :Meets at Workhouse, after Guardians' meeting. House as the scene of the event; the Hinton estate is Clerk, Edward Roy Longcroft, Havant now held by Hyde Salmon Whalley-Tooker esq. J.P. Treasurer, William Grant, Portsmouth who is a lineal descendant in the female line: the man· Medical Officer of Health, Charles Nash L.R.C.P.Lond. sion, erected in 1868, on the site of old Hinton House, is Tlie Yews, Horndean a building of flint stone, pleasantly situated and com Sanitary Inspector & Road Surveyor, Charles Clark, manding some extensive views. Bere Forest is partly Waterlooville within the parish. Hyde Salmon Whalley-Tooker esq. Catherington Union. J.P. of Hinton Daubnay, who holds the manorial rights, Board day, alternate tuesday.s, at the workhouse, Sir .Arthur Henry Clarke-Jervoise hart. of Idsworth Horndean park, and George .Alexander Gale esq. are the principal The nnion comprises the following places :-Blendworth, landowners. The soil varies from a loam and chalk to Catherington, Chalton, Claufield, ldsworth, & Water stiff clay; .subsoil, chalk and clay. The chief crops are looville; area, 13,145 acres; rateable value in 1898, wheat, barley and oats. The parish and hamlets contain £r5,62B; the population of the union in 1891 was 2,990 s.q.o acres; rateable value, £6,456; the population of Clerk to the Guardians & .Assessment Committee, Ed th9 civll parish in r8gt was I,fi3, including part of Den ward Roy Longcroft, Havant .Dlead and 23 officers and inmates of the Workhouse at Treasurer, William Grant, High street, Portsmouth Horndean.