When the New York Times Declared That Coca-Cola Was No Longer to Be Publically Persecuted, It Lacked the Foresight to Know That

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BREAKING Newsrockville, MD August 19, 2019

MEDIA KIT BREAKING NEWS Rockville, MD August 19, 2019 THE BOYS by Garth Ennis and Darick Robertson Coming to GraphicAudio® A Movie in Your Mind® in Early 2020 GraphicAudio® is thrilled to announce a just inked deal with DYNAMITE COMICS to produce and publish all 6 Omnibus Volumes of THE BOYS directly from the comics and scripted and produced in their unique audio entertainment format. The creative team at GraphicAudio® plans to make the adaptations as faithful as possible to the Graphic Novel series. The series is set between 2006–2008 in a world where superheroes exist. However, most of the su- perheroes in the series' universe are corrupted by their celebrity status and often engage in reckless behavior, compromising the safety of the world. The story follows a small clandestine CIA squad, informally known as "The Boys", led by Butcher and also consisting of Mother's Milk, the French- man, the Female, and new addition "Wee" Hughie Campbell, who are charged with monitoring the superhero community, often leading to gruesome confrontations and dreadful results; in parallel, a key subplot follows Annie "Starlight" January, a young and naive superhero who joins the Seven, the most prestigious– and corrupted – superhero group in the world and The Boys' most powerful enemies. Amazon Prime released THE BOYS Season 1 last month. Joseph Rybandt, Executive Editor of Dynamite and Editor of The Boys says, “While I did not grow up anywhere near the Golden Age of Radio, I have loved the medium of radio and audio dramas almost my entire life. Podcasts make my commute bearable to this day. -

‚Every Day Is 9/11!•Ž: Re-Constructing Ground Zero In

JUCS 4 (1+2) pp. 241–261 Intellect Limited 2017 Journal of Urban Cultural Studies Volume 4 Numbers 1 & 2 © 2017 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/jucs.4.1-2.241_1 MARTIN LUND Linnaeus University ‘Every day is 9/11!’: Re-constructing Ground Zero in three US comics ABSTRACT KEYWORDS This article analyses three comics series: writer Brian K. Vaughan and artist Tony comics Harris’ Ex Machina (August 2004–August 2010); writer Brian Wood and artist Ground Zero Riccardo Burchielli’s DMZ (November 2005–February 2012); and writer Garth 9/11 Ennis and artist Darick Robertson’s The Boys (October 2006–November 2012). archifictions Taking literary critic Laura Frost’s concept of ‘archifictions’ as its starting point, the War on Terror article discusses how these series frame the September 11 attacks on New York and architecture their aftermath, but its primary concern is with their engagement with the larger social ramifications of 9/11 and with the War on Terror, and with how this engage- ment is rooted in and centred on Ground Zero. It argues that this rooting allows these comics’ creators to critique post-9/11 US culture and foreign policy, but that it also, ultimately, serves to disarm the critique that each series voices in favour of closure through recourse to recuperative architecture. The attacks on September 11 continue to be felt in US culture. Comics are no exception. Comics publishers, large and small, responded immediately and comics about the attacks or the War on Terror have been coming out ever since. Largely missing from these comics, however, is an engagement with Ground Zero; after depicting the Twin Towers struck or falling, artists and writers rarely give the area a second thought. -

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II a Master's Thesis Presented to College of Arts & Sciences Departmen

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II A Master’s Thesis Presented To College of Arts & Sciences Department of Communications and Humanities _______________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree _______________________________ SUNY Polytechnic Institute By David Dellecese May 2018 © 2018 David Dellecese Approval Page SUNY Polytechnic Institute DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS AND HUMANITIES INFORMATION DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY MS PROGRAM Approved and recommended for acceptance as a thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Information Design + Technology. _________________________ DATE ________________________________________ Kathryn Stam Thesis Advisor ________________________________________ Ryan Lizardi Second Reader ________________________________________ Russell Kahn Instructor 1 ABSTRACT American comic books were a relatively, but quite popular form of media during the years of World War II. Amid a limited media landscape that otherwise consisted of radio, film, newspaper, and magazines, comics served as a useful tool in engaging readers of all ages to get behind the war effort. The aims of this research was to examine a sampling of messages put forth by comic book publishers before and after American involvement in World War II in the form of fictional comic book stories. In this research, it is found that comic book storytelling/messaging reflected a theme of American isolation prior to U.S. involvement in the war, but changed its tone to become a strong proponent for American involvement post-the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This came in numerous forms, from vilification of America’s enemies in the stories of super heroics, the use of scrap, rubber, paper, or bond drives back on the homefront to provide resources on the frontlines, to a general sense of patriotism. -

John Constantine and the Homoaffective Question: an Analysis of LGBTI+ Representations in Superhero Comics and Animations

John Constantine and the homoaffective question: an analysis of LGBTI+ representations in superhero comics and animations JOHN CONSTANTINE AND THE HOMOAFFECTIVE QUESTION: AN ANALYSIS OF LGBTI+ REPRESENTATIONS IN SUPERHERO COMICS AND ANIMATIONS JOHN CONSTANTINE E A QUESTÃO HOMOAFETIVA: UMA ANÁLISE SOBRE REPRESENTAÇÕES LGBTI+ EM QUADRINHOS DE SUPER-HERÓIS E ANIMAÇÕES JOHN CONSTANTINE Y LA PREGUNTA HOMOAFFECTIVE: UN ANÁLISIS DE LAS REPRESENTACIONES LGBTI+ EN CÓMICS DE SUPERHÉROES Y ANIMACIONES Mário Jorge de PAIVA1 ABSTRACT: This article is an analysis of LGBTI + representations in comic books, superheroes, and children's animations. In particular, we will approach the character of DC Comics John Constantine, bisexual, because he is a hero of a major publisher, appearing alongside Batman, Superman etc. Our methodology is qualitative, based on a broad contribution containing: Michel Foucault, Sarane Alexandrian, James Green, João Trevisan, Dandara Cruz among others. Our conclusions involve seeing how there has really been a profound change over time. If before this type of question could not be addressed as much, or could not be addressed explicitly, today there is a greater opening for representations of LGBTI + characters. KEYWORDS: LGBTI+. Comics. Animations. John Constantine. Hellblazer. RESUMO: O presente artigo é uma análise das representações LGBTI+ em revistas de super-heróis e animações. Abordaremos mais a personagem da DC Comics John Constantine, bissexual, por ele ser um herói de uma grande editora, aparecendo junto ao Batman, Superman etc. Nossa metodologia é qualitativa, se pautando em uma análise inicial do campo de estudos e na sequência em uma análise mais aprofundada da própria personagem Constantine. Possuímos um aporte teórico que envolve, entre outros autores: Michel Foucault, Sarane Alexandrian e Dandara Cruz. -

The Portrayal of Women in American Superhero Comics By: Esmé Smith Junior Research Project Seminar

Hidden Heroines: The Portrayal of Women in American Superhero Comics By: Esmé Smith Junior Research Project Seminar Introduction The first comic books came out in the 1930s. Superhero comics quickly became one of the most popular genres. Today, they remain incredibly popular and influential. I have been interested in superhero comics for several years now, but one thing I often noticed was that women generally had much smaller roles than men and were also usually not as powerful. Female characters got significantly less time in the story devoted to them than men, and most superhero teams only had one woman, if they had any at all. Because there were so few female characters it was harder for me to find a way to relate to these stories and characters. If I wanted to read a comic that centered around a female hero I had to spend a lot more time looking for it than if I wanted to read about a male hero. Another thing that I noticed was that when people talk about the history of superhero comics, and the most important and influential superheroes, they almost only talk about male heroes. Wonder Woman was the only exception to this. This made me curious about other influential women in comics and their stories. Whenever I read about the history of comics I got plenty of information on how the portrayal of superheroes changed over time, but it always focused on male heroes, so I was interested in learning how women were portrayed in comics and how that has changed. -

X-Force by Craig Kyle & Chris Yost: the Complete Collection Volume 2

X-FORCE BY CRAIG KYLE & CHRIS YOST: THE COMPLETE COLLECTION VOLUME 2 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Craig Kyle,Christopher Yost,Clayton Crain,Mike Choi | 384 pages | 09 Sep 2014 | Marvel Comics | 9780785190004 | English | New York, United States X-Force by Craig Kyle & Chris Yost: the Complete Collection Volume 2 PDF Book Rahne and Hrimhari could easily have had their own book for their sublot. However if there is one person you do not want to conner it is X Jon Stevens rated it really liked it May 15, He teleports to each one, getting sliced, shot, and attacked at each one before Elixir touches him mumbling an apology. Collectibles Paperback Books. Chris Curtis rated it really liked it Sep 03, Of course we also get some just plain awesome fight scenes between Bastion and Wolverine, and Archangel kills dozens of Purifiers in a fit of rage. This created some major advantages and disadvantages to normal event structures. Esequesoy rated it really liked it Mar 26, If any characters lends themselves to horror movie style characters it is these guys. By continuing to use this website, you agree to their use. Kayleigh rated it liked it Nov 13, To ensure we are able to help you as best we can, please include your reference number:. The starts from issues 17 where they snap back to their time. Add to list. How was your experience with this page? Vanisher freaks out and reminds me of that classic whiny sidekick villain from a kids movie, but here done in a legitimately funny and enjoyable way. -

What Superman Teaches Us About the American Dream and Changing Values Within the United States

TRUTH, JUSTICE, AND THE AMERICAN WAY: WHAT SUPERMAN TEACHES US ABOUT THE AMERICAN DREAM AND CHANGING VALUES WITHIN THE UNITED STATES Lauren N. Karp AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Lauren N. Karp for the degree of Master of Arts in English presented on June 4, 2009 . Title: Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States Abstract approved: ____________________________________________________________________ Evan Gottlieb This thesis is a study of the changes in the cultural definition of the American Dream. I have chosen to use Superman comics, from 1938 to the present day, as litmus tests for how we have societally interpreted our ideas of “success” and the “American Way.” This work is primarily a study in culture and social changes, using close reading of comic books to supply evidence. I argue that we can find three distinct periods where the definition of the American Dream has changed significantly—and the identity of Superman with it. I also hypothesize that we are entering an era with an entirely new definition of the American Dream, and thus Superman must similarly change to meet this new definition. Truth, Justice, and the American Way: What Superman Teaches Us about the American Dream and Changing Values within the United States by Lauren N. Karp A THESIS submitted to Oregon State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Presented June 4, 2009 Commencement June 2010 Master of Arts thesis of Lauren N. Karp presented on June 4, 2009 APPROVED: ____________________________________________________________________ Major Professor, representing English ____________________________________________________________________ Chair of the Department of English ____________________________________________________________________ Dean of the Graduate School I understand that my thesis will become part of the permanent collection of Oregon State University libraries. -

Beyond Super Heroes and Talking Animals: Social Justice in Graphic Novels in Education

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Pepperdine Digital Commons Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2017 Beyond super heroes and talking animals: social justice in graphic novels in education David Greenfield Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Recommended Citation Greenfield, David, "Beyond super heroes and talking animals: social justice in graphic novels in education" (2017). Theses and Dissertations. 898. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/898 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected] , [email protected]. Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology BEYOND SUPER HEROES AND TALKING ANIMALS: SOCIAL JUSTICE IN GRAPHIC NOVELS IN EDUCATION A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Learning Technologies by David Greenfield December, 2017 Linda G. Polin, Ph.D. ‒ Dissertation Chairperson This dissertation, written by David Greenfield under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted to and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Doctoral Committee: Linda -

Freemen, Slaves?

No. 51. FREEMEN, SLAVES? BY GEORGE W. BUNGAY. 'OU say that you are fl'ee——a free man :—-that you work with free hands and walk with ii-ee feet; that you are the master of your own bones and brains; that you can think your own thoughts and put your thoughts into words and deeds; that you can go from place to place without a pass. You can work or play. You can earn money and spend it or save it. You can learn how to read and write, or you can remain ignorant of the use of letters. You can be a good sober man, or you can become a poor, miserable drunkard. Now there is more than one kind of slavery, and the man who is a drunkard, whether he be black or white, is a slave, and habit-the habit of drinkin.g—,is his master. It is a cruel master, for it takes his wages from him, and does not give him bread to eat nor clothes I0 wear in re turn for the monpy. He spends his money for rum, or gin, or brandy, or wine, or beer. and gets a. pain in the head or a bad feeling in the stomach for it. The drink does not make him smarter ncr stronger than he was before he drank it. I-Ie may feel wise and strong for a short time after drivking,_ but it merely excites him as the whip and the spur excite the horse. A horse will go fast when you whip him and spur him, but whips and spurs will not make him fat and strong. -

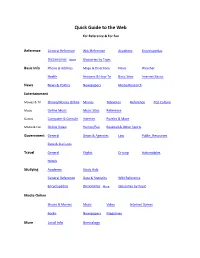

Quick Guide to the Web

Quick Guide to the Web For Reference & For Fun Reference General Reference Wiki Reference Academic Encyclopedias Dictionaries More Glossaries by Topic Basic Info Phone & Address Maps & Directions News Weather Health Answers & How-To Basic Sites Internet Basics News News & Politics Newspapers Media Research Entertainment Movies & TV Shows/Movies Online Movies Television Reference Pop Culture Music Online Music Music Sites Reference Games Computer & Console Internet Puzzles & More Media & Fun Online Video Humor/Fun Baseball & Other Sports Government General Depts & Agencies Law Public_Resources Data & Statistics Travel General Flights Driving Automobiles Hotels Studying Academic Study Aids General Reference Data & Statistics Wiki Reference Encyclopedias Dictionaries More Glossaries by Topic Media Online Shows & Movies Music Video Internet Games Books Newspapers Magazines More Local Info Genealogy Finding Basic Information Basic Search & More Google Yahoo Bing MSN ask.com AOL Wikipedia About.com Internet Public Library Freebase Librarian Chick DMOZ Open Directory Executive Library Web Research OEDB LexisNexis Wayback Machine Norton Site-Checker DigitalResearchTools Web Rankings Alexa Web Tools - Librarian Chick Web 2.0 Tools Top Reference & Resources – Internet Quick Links E-map | Indispensable Links | All My Faves | Joongel | Hotsheet | Quick.as Corsinet | Refdesk Tools | CEO Express Internet Resources Wayback Machine | Alexa | Web Rankings | Norton Site-Checker Useful Web Tools DigitalResearchTools | FOSS Wiki | Librarian Chick | Virtual -

X-Men Archives Checklist

X-Men Archives Checklist Base Cards # Card Title [ ] 01 Title Card [ ] 02 Angel [ ] 03 Armor [ ] 04 Beast [ ] 05 Bishop [ ] 06 Blink [ ] 07 Cable [ ] 08 Caliban [ ] 09 Callisto [ ] 10 Cannonball [ ] 11 Captain Britain [ ] 12 Chamber [ ] 13 Colossus [ ] 14 Cyclops [ ] 15 Dazzler [ ] 16 Deadpool [ ] 17 Domino [ ] 18 Dust [ ] 19 Elixir [ ] 20 Emma Frost/White Queen [ ] 21 Forge [ ] 22 Gambit [ ] 23 Guardian [ ] 24 Havok [ ] 25 Hellion [ ] 26 Icarus [ ] 27 Iceman [ ] 28 Ink [ ] 29 Jean Grey [ ] 30 Jubilee [ ] 31 Karma [ ] 32 Kuan-Yin Xorn [ ] 33 Lilandra [ ] 34 Longshot [ ] 35 M [ ] 36 Magik [ ] 37 Magma [ ] 38 Marvel Girl [ ] 39 Mercury [ ] 40 Mimic [ ] 41 Mirage [ ] 42 Morph [ ] 43 Multiple Man [ ] 44 Nightcrawler [ ] 45 Northstar [ ] 46 Omega Sentinel [ ] 47 Pixie [ ] 48 Polaris [ ] 49 Prodigy [ ] 50 Professor Xavier [ ] 51 Psylocke [ ] 52 Quicksilver [ ] 53 Rockslide [ ] 54 Rogue [ ] 55 Sage [ ] 56 Shadowcat [ ] 57 Shatterstar [ ] 58 Shola Inkosi [ ] 59 Siryn [ ] 60 Starjammers [ ] 61 Storm [ ] 62 Strong Guy [ ] 63 Sunfire [ ] 64 Sunspot [ ] 65 Surge [ ] 66 Wallflower [ ] 67 Warpath [ ] 68 Wicked [ ] 69 Wind Dancer [ ] 70 Wolfsbane [ ] 71 Wolverine [ ] 72 X-23 Nemesis (1:8 packs) # Card Title [ ] N1 Mr. Sinister by Greg Land [ ] N2 Magneto by Sean Chen and Sandu Florea [ ] N3 Mystique by Mike Mayhew [ ] N4 Sabretooth by Paolo Rivera [ ] N5 Mojo by Frank Cho [ ] N6 Apocalypse by Salvador Larroca [ ] N7 Juggernaut by Sean Chen [ ] N8 Sentinels by Marc Silvestri and Joe Weems [ ] N9 Brotherhood of Evil Mutants by David Finch Cover Gallery -

Steve Geppi's Members-Only Tour At

*FCBD 2014 int with covers.qxp_Layout 1 1/31/14 12:58 PM Page c1 2014 OVERSTREET’S® MARKETPLACEMARKETPLACE BILLY TUCCI’S TURNS 20! BATMAN AT 75! THE ORIGIN OF THE WINTER SOLDIER! *FCBD 2014 int with covers.qxp_Layout 1 1/31/14 12:58 PM Page 5 MMILESTONESILESTONES EEXHIBITXHIBIT SSHOWCASESHOWCASES AAFRICANFRICAN-A-AMERICANMERICAN CCREATORSREATORS Kicking off with an invitation- only celebration, Milestones: African Americans in Comics, Pop Culture (Left to right) Co-Curator Tatiana El-Khouri, Curator Michael Davis, and Beyond launched at Geppi’s GEM President Melissa Bowersox, GEM Founder Steve Geppi and Entertainment Museum (GEM) on Friday Milestone Media Co-Founder Denys Cowan. night, December 13, 2013. The exhibit opened to the public the next morning and is scheduled to run through August 10, 2014. Milestones, which is curated by Milestone Media’s Michael Davis and co-curated by Tatiana EL-Khouri, offers patrons a full spectrum of Black historic contributions made throughout comic book and graphic novel history. The exhibit grew out of initial discussions between GEM President Melissa (Missy) Bowersox and Davis three years earli- er. They had lamented together the absence of a force like the late writer-editor Dwayne McDuffie, and together they seized on the idea of Milestones. “When Missy asked me to curate something, the easiest way to go was to do Milestones retrospective because Milestone has always been inclusive. I wanted to showcase established African American artists, but also the guys who came before us, including Don McGregor. Don invented Sabre, which is one of the premier African American comics, invented by a white guy.