For Adding a Threatening Process Under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Water Consumption by Rusa Deer (Cervus Timorensis) Stags As Infl Uenced by Different Types of Food

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Queensland eSpace Animal Science 2005, 80: 83-88 Water intake of rusa stags in Australia 1357-7298/04/40500083$20.00 © 2005 British Society of Animal Science Water consumption by rusa deer (Cervus timorensis) stags as infl uenced by different types of food W. Yape Kii and G. McL. Dryden† School of Animal Studies, University of Queensland, Gatton, Queensland 4345, Australia †Email : [email protected] Abstract During winter in southern Queensland, eight rusa deer stags aged 4 years were given ad libitum lucerne (Medicago sativa) hay and confi ned in individual metabolism pens for 26 days. Stags ate 2·04 kg dry matter (DM) per day and drank 6·4 kg water per day, while the drinking water : food DM ratio was 3·3 l/kg. In experiment 2, seven rusa stags were given ad libitum lucerne hay or oaten (Avena spp. ) hay with or without barley grain supplementation (200 g/day) for 56 days (four periods). This experiment was conducted from 26 July to 19 September 2001, when the stags were exhibiting the behaviour characteristic of the rut. Rusa stags ate 1·19 and 1·17 kg DM per day of lucerne and oaten hay respectively. Rusa stags given oaten hay drank slightly more water than those that received lucerne hay (5·34 and 4·47 kg/day, respectively). The drinking water : food DM ratios were 3·81 and 4·67 kg/kg for lucerne and oaten hay, respectively. -

Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout Has in THIS ISSUE Dbeen Awarded the President’S Cup Letter from the President

DSC NEWSLETTER VOLUME 32,Camp ISSUE 5 TalkJUNE 2019 Pending World Record Waterbuck Wins Top Honor SC Life Member Susan Stout has IN THIS ISSUE Dbeen awarded the President’s Cup Letter from the President .....................1 for her pending world record East African DSC Foundation .....................................2 Defassa Waterbuck. Awards Night Results ...........................4 DSC’s April Monthly Meeting brings Industry News ........................................8 members together to celebrate the annual Chapter News .........................................9 Trophy and Photo Award presentation. Capstick Award ....................................10 This year, there were over 150 entries for Dove Hunt ..............................................12 the Trophy Awards, spanning 22 countries Obituary ..................................................14 and almost 100 different species. Membership Drive ...............................14 As photos of all the entries played Kid Fish ....................................................16 during cocktail hour, the room was Wine Pairing Dinner ............................16 abuzz with stories of all the incredible Traveler’s Advisory ..............................17 adventures experienced – ibex in Spain, Hotel Block for Heritage ....................19 scenic helicopter rides over the Northwest Big Bore Shoot .....................................20 Territories, puku in Zambia. CIC International Conference ..........22 In determining the winners, the judges DSC Publications Update -

NPWS Pocket Guide 3E (South Coast)

SOUTH COAST 60 – South Coast Murramurang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 61 PARK LOCATIONS 142 140 144 WOLLONGONG 147 132 125 133 157 129 NOWRA 146 151 145 136 135 CANBERRA 156 131 148 ACT 128 153 154 134 137 BATEMANS BAY 139 141 COOMA 150 143 159 127 149 130 158 SYDNEY EDEN 113840 126 NORTH 152 Please note: This map should be used as VIC a basic guide and is not guaranteed to be 155 free from error or omission. 62 – South Coast 125 Barren Grounds Nature Reserve 145 Jerrawangala National Park 126 Ben Boyd National Park 146 Jervis Bay National Park 127 Biamanga National Park 147 Macquarie Pass National Park 128 Bimberamala National Park 148 Meroo National Park 129 Bomaderry Creek Regional Park 149 Mimosa Rocks National Park 130 Bournda National Park 150 Montague Island Nature Reserve 131 Budawang National Park 151 Morton National Park 132 Budderoo National Park 152 Mount Imlay National Park 133 Cambewarra Range Nature Reserve 153 Murramarang Aboriginal Area 134 Clyde River National Park 154 Murramarang National Park 135 Conjola National Park 155 Nadgee Nature Reserve 136 Corramy Regional Park 156 Narrawallee Creek Nature Reserve 137 Cullendulla Creek Nature Reserve 157 Seven Mile Beach National Park 138 Davidson Whaling Station Historic Site 158 South East Forests National Park 139 Deua National Park 159 Wadbilliga National Park 140 Dharawal National Park 141 Eurobodalla National Park 142 Garawarra State Conservation Area 143 Gulaga National Park 144 Illawarra Escarpment State Conservation Area Murramarang National Park. Photo: D Finnegan/OEH South Coast – 63 BARREN GROUNDS BIAMANGA NATIONAL PARK NATURE RESERVE 13,692ha 2,090ha Mumbulla Mountain, at the upper reaches of the Murrah River, is sacred to the Yuin people. -

Eucalyptus Baeuerlenii

Euclid - Online edition Eucalyptus baeuerlenii Baeuerlen's gum Classification Eucalyptus | Symphyomyrtus | Maidenaria | Euryotae | Saxicola Nomenclature Eucalyptus baeuerlenii F.Muell., Victorian Naturalist 7: 76 (1890). E. viminalis var. baeuerlenii (F.Muell.) H.Deane & Maiden, Proc. Linn. Soc. New South Wales 26: 142 (1901). T: Sugar Loaf Mtn towards sources of the Clyde R., NSW, 1890, W.Bäuerlen s.n.; holo: MEL; iso: K. Description Mallee to 10 m tall, or tree to 20 m tall. Forming a lignotuber. Bark smooth, pink, brown, grey, cream or green. Juvenile growth (coppice or field seedlings to 50 cm): stem rounded or square in cross- section, warty or smooth; juvenile leaves opposite for 10 to 15 nodes, becoming alternate but often reverting for a few nodes, sessile or petiolate, lanceolate, 3.5–9.5 cm long, 1.3–2.8 cm wide, green or slightly grey-green. Adult leaves alternate, petiole 0.5–1.8 cm long; blade lanceolate to falcate, 7–17.5 cm long, 0.6–3 cm wide, base tapering to petiole, concolorous, glossy or dull, green, side-veins greater than 45° to midrib, moderately to densely reticulate, intramarginal vein parallel to and just within margin, oil glands island and intersectional. Inflorescence axillary unbranched, peduncles 0.2–0.5 cm long, buds 3 per umbel, usually sessile, rarely with pedicels to 0.2 cm long. Mature buds oblong to fusiform, 0.7–1 cm long, 0.4–0.6 cm wide, green to yellow, usually warty, slightly angled, scar present, operculum beaked to conical, stamens inflexed or irregularly flexed, anthers cuboid to oblong, versatile, dorsifixed, dehiscing by longitudinal slits (non-confluent), style long, locules 3 or 4(5) each with 4 vertical ovule rows. -

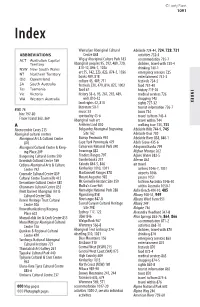

Australia-15-Index.Pdf

© Lonely Planet 1091 Index Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Adelaide 724-44, 724, 728, 731 ABBREVIATIONS Centre 848 activities 732-3 ACT Australian Capital Wigay Aboriginal Culture Park 183 accommodation 735-7 Territory Aboriginal peoples 95, 292, 489, 720, children, travel with 733-4 NSW New South Wales 810-12, 896-7, 1026 drinking 740-1 NT Northern Territory art 55, 142, 223, 823, 874-5, 1036 emergency services 725 books 489, 818 entertainment 741-3 Qld Queensland culture 45, 489, 711 festivals 734-5 SA South Australia festivals 220, 479, 814, 827, 1002 food 737-40 Tas Tasmania food 67 history 719-20 INDEX Vic Victoria history 33-6, 95, 267, 292, 489, medical services 726 WA Western Australia 660, 810-12 shopping 743 land rights 42, 810 sights 727-32 literature 50-1 tourist information 726-7 4WD 74 music 53 tours 734 hire 797-80 spirituality 45-6 travel to/from 743-4 Fraser Island 363, 369 Aboriginal rock art travel within 744 A Arnhem Land 850 walking tour 733, 733 Abercrombie Caves 215 Bulgandry Aboriginal Engraving Adelaide Hills 744-9, 745 Aboriginal cultural centres Site 162 Adelaide Oval 730 Aboriginal Art & Cultural Centre Burrup Peninsula 992 Adelaide River 838, 840-1 870 Cape York Penninsula 479 Adels Grove 435-6 Aboriginal Cultural Centre & Keep- Carnarvon National Park 390 Adnyamathanha 799 ing Place 209 Ewaninga 882 Afghan Mosque 262 Bangerang Cultural Centre 599 Flinders Ranges 797 Agnes Water 383-5 Brambuk Cultural Centre 569 Gunderbooka 257 Aileron 862 Ceduna Aboriginal Arts & Culture Kakadu 844-5, 846 air travel Centre -

Javan Rhino Expedition

Javan Rhino Expedition th th Destination: Java, Indonesia Duration: 10 Days Dates: 7 – 16 June 2018 Having amazing close encounters with 2 different Javan Rhinos in just one day! Enjoying the expertise of some of Ujung Kulon’s finest guides & rangers Great sightings of various kingfishers and heron species along the rivers Trekking & camping deep inside the core zone of Ujung Kulon National Park Finding very fresh evidence of at least 2 different rhinos from when we were there Seeing over 50 species of birds throughout including Green Peafowl & Elegant Pitta Spotlighing banteng, Sunda leopard cat & Javan mousedeer along the river banks Canoeing down the river where more Javan rhinos have been seen than anywhere Coming across a beautiful neonate Malayan pit viper along one of the trails Enjoying speed boat transfers around the stunning coastline of Ujung Kulon NP Tour Leader / Guides Overview Martin Royle (Royle Safaris Tour Leader) Chinglus (Lead Ujung Kulon Guide) Meeta & Udung (Ujung Kulon Rangers) Day 1: Jakarta / Adun, Geni, Wilum, Bambu, Wilf, Nurlin, Asif (Porters) Carita / Edy (Transfer driver) Ujung Kulon Ciggaman (Boat transfer skipper) Participants Days 2-8: Ujung Kulon Dr. Jacoba Brinkman Mr. Phillip DuCros Mr. Andrew Holman Mrs. Paula Holman Day 9: Ujung Kulon / Handeleum Island Day 10: Carita / Jakarta Day 11: Home Royle Safaris – 6 Greenhythe Rd, Heald Green, Cheshire, SK8 3NS – 0845 226 8259 – [email protected] Day by Day Breakdown Overview With only five species of rhinos in the world you would think that everyone would know about all five, there are not that many. But there are two that largely go unnoticed. -

The Phylogenetic Roots of Human Lethal Violence José María Gómez1,2, Miguel Verdú3, Adela González-Megías4 & Marcos Méndez5

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature19758 The phylogenetic roots of human lethal violence José María Gómez1,2, Miguel Verdú3, Adela González-Megías4 & Marcos Méndez5 The psychological, sociological and evolutionary roots of 600 human populations, ranging from the Palaeolithic era to the present conspecific violence in humans are still debated, despite attracting (Supplementary Information section 9c). The level of lethal violence the attention of intellectuals for over two millennia1–11. Here we was defined as the probability of dying from intraspecific violence propose a conceptual approach towards understanding these roots compared to all other causes. More specifically, we calculated the level based on the assumption that aggression in mammals, including of lethal violence as the percentage, with respect to all documented humans, has a significant phylogenetic component. By compiling sources of mortality, of total deaths due to conspecifics (these sources of mortality from a comprehensive sample of mammals, were infanticide, cannibalism, inter-group aggression and any other we assessed the percentage of deaths due to conspecifics and, type of intraspecific killings in non-human mammals; war, homicide, using phylogenetic comparative tools, predicted this value for infanticide, execution, and any other kind of intentional conspecific humans. The proportion of human deaths phylogenetically killing in humans). predicted to be caused by interpersonal violence stood at 2%. Lethal violence is reported for almost 40% of the studied mammal This value was similar to the one phylogenetically inferred for species (Supplementary Information section 9a). This is probably the evolutionary ancestor of primates and apes, indicating that a an underestimation, because information is not available for many certain level of lethal violence arises owing to our position within species. -

Zoologische Mededelingen Uitgegeven Door Het

ZOOLOGISCHE MEDEDELINGEN UITGEGEVEN DOOR HET RIJKSMUSEUM VAN NATUURLIJKE HISTORIE TE LEIDEN (MINISTERIE VAN CULTUUR, RECREATIE EN MAATSCHAPPELIJK WERK) Deel 45 no. 7 15 Februari 1971 ON THE IDENTITY OF CERVUS NIGRICANS BROOKE, 1877, WITH REMARKS UPON OTHER DEER FROM THE PHILIPPINES by L. J. DOBRORUKA Zoological Garden, Prague With 2 text-figures and 3 plates A great number of papers deal with the deer of the Philippine Islands but in spite of this fact the taxonomy and the nomenclature are still not clear. The first author who recapitulated all known facts about the Philippine deer was Brooke (1877), who also described a new species, Cervus nigricans. The description is exact, with figures of the habitus and the skull of the indicated holotype (♀), and in my opinion Haltenorth (1963) had no reason to con- sider C. nigricans a nomen nudum. The validity of the name Cervus nigricans is in full agreement with the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, adopted by the XVth International Congress of Zoology. Cervus nigricans is rather rare in the collections of museums and, there- fore, I am much obliged to Dr. A. M. Husson for allowing me to examine the material of the Rijksmuseum van Natuurlijke Historie in Leiden. The material of this museum was mentioned already in Brooke's paper (1877:59) and is therefore most valuable for a study of this species, apart from the type material, of course. At the present time the following material of this species is available in the Leiden Museum: No. 19605 ♂ — mounted specimen and skull from Manila, Philippines. Presented by M. -

Northern Rivers Feral Deer Identification Guide

Northern Rivers Feral Deer Identification Guide Menil (spotted) Fallow Buck, Western Sydney Parklands. Fallow Deer (Dama dama) Chital Deer (Axis axis) Introduction and distribution Introduction and distribution Fallow Deer were introduced to Tasmania in the 1830’s Chital Deer were introduced to Australia from India and mainland Australia around the 1880’s from Europe. in the 1860s. Wild populations of Chital exist in Fallow deer are the most widespread and established Queensland near Charters Towers, with other smaller of the feral deer species in Australia. They occur in isolated population in NSW, South Australia and Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and Victoria. Range and densities are increasing from South Australia. isolated pockets and deliberate release for hunting. Habitat and herding Habitat and herding The Fallow Deer are a herd deer inhabiting semi-open Chital deer are herbivores that browse on a variety of scrubland and frequent and graze on pasture that grasses, fruit and leaves. They are gregarious and can is in close proximity to cover. They breed during the form groups of more than 100 individuals. They do April/May, fawns are born in December and the bucks not have a defined breeding season, and are capable cast their antlers in October. Antlers are regrown by of producing three offspring in two years. Chital deer February. In rut, the buck makes an unmistakable will eat their shed antlers if their diet is lacking the croak, similar to a grunting pig. The calls vary from vitamins and minerals. Females will separate from the high pitched bleating to deep grunts. -

Pomaderris Gilmourii

Plants of South Eastern New South Wales Leafy stem (var. gilmourii). Photographer Jackie Miles, Deua National Park Stem with young seed cases. (var. gilmourii). Photographer Jackie Miles, Deua National Park Common name Grey Deua pomaderris (var. cana) Family Rhamnaceae Where found Open forest and shrubland on rhyolite outcrops. Mainly ranges west of Moruya, in Deua National Park. One record on the Brogo River in Wadbilliga National Park. var. cana: Ranges in Deua National Park west of Moruya. var. gilmourii: Ranges. Mainly Deua National Park. One record in Wadbilliga National Park. Notes Shrub to 4 m high. Young stems with more or less appressed simple or clustered hairs (needs a hand lens or a macro app on your phone/tablet to see). Leaves alternating up the stems, 0.5–3.5 cm long, 2–12 mm wide, upper surface hairless, lower surface with a short greyish tomentum, all hairs more or less the same length, lateral veins distinct, 3–6 pairs, looping to the inside and not reaching the leaf margins. Flowers cream to yellow, with 5 sepals about 1.5 mm long, falling early, and 0 petals. flower buds silvery. Flowers in branched clusters shorter than the leaves. var. cana: No dense superficial layer of more or less woolly simple hairs, on the lower surface of the leaves, leaf stalks, branchlets etc. Surfaces appearing dull. Leaf margins neither thickened or hairless, not apparent as a border on either surface. Sepals about 1 mm long. Style hairy above the point of division. Vulnerable Australia. Vulnerable NSW. Provisions of the Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 No 63 relating to the protection of protected plants generally also apply to plants that are a threatened species. -

Ungulate Tag Marketing Profiles

AZA Ungulates Marketing Update 2016 AZA Midyear Meeting, Omaha NE RoxAnna Breitigan -The Living Desert Michelle Hatwood - Audubon Species Survival Center Brent Huffman -Toronto Zoo Many hooves, one herd COMMUNICATION Come to TAG meetings! BUT it's not enough just to come to the meetings Consider participating! AZAUngulates.org Presentations from 2014-present Details on upcoming events Husbandry manuals Mixed-species survey results Species profiles AZAUngulates.org Content needed! TAG pages Update meetings/workshops Other resources? [email protected] AZAUngulates.org DOUBLE last year’s visits! Join our AZA Listserv [AZAUngulates] Joint Ungulate TAG Listserv [email protected] To manage your subscription: http://lists.aza.org/cgi-bin/mailman/listinfo/azaungulates Thanks to Adam Felts (Columbus Zoo) for moderating! Find us on Facebook www.facebook.com/AZAUngulates/ 1,402 followers! Thanks to Matt Ardaiolo (Denver Zoo) for coordinating! Joining forces with IHAA International Hoofstock Awareness Association internationalhoofstock.org facebook.com INITIATIVES AZA SAFE (Saving Animals From Extinction) AZA initiative Launched in 2015 Out of 144 nominations received, 24 (17%) came from the Ungulate TAGs (all six TAGs had species nominated). Thank you to everyone who helped!!! Marketing Profiles •Audience: decision makers •Focus institutional interest •Stop declining trend in captive ungulate populations •63 species profiles now available online Marketing Profiles NEW for this year! Antelope & Giraffe TAG Caprinae TAG Black -

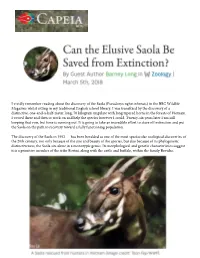

I Vividly Remember Reading About the Discovery of the Saola (Pseudoryx

I vividly remember reading about the discovery of the Saola (Pseudoryx nghetinhensis) in the BBC Wildlife Magazine whilst sitting in my traditional English school library. I was transfixed by the discovery of a distinctive, one-and-a-half-meter long, 70 kilogram ungulate with long tapered horns in the forests of Vietnam. I vowed there and then to work on and help the species however I could. Twenty-six years later I am still keeping that vow, but time is running out. It is going to take an incredible effort to stave off extinction and put the Saola on the path to recovery toward a fully functioning population. The discovery of the Saola in 1992 has been heralded as one of the most spectacular zoological discoveries of the 20th century, not only because of the size and beauty of the species, but also because of its phylogenetic distinctiveness; the Saola sits alone in a monotypic genus. Its morphological and genetic characteristics suggest it is a primitive member of the tribe Bovini, along with the cattle and buffalo, within the family Bovidae. The Saola is found in the North and Central Annamite Mountains of Vietnam and Laos where it is restricted to climatically wet evergreen, broadleaf forest habitats. These forests are subjected to an up to 10-month long rainy season, with no month receiving less than 40 mm of rain. This level of rainfall is the result of two monsoons, and determines the Saola’s distribution. The western and southern distribution of the Saola are bounded by the rain shadow of mountain chains with the western extent expanding deeper into Laos where the mountains dip, allowing deeper penetration of the northeast winter monsoon.