Gordon Steele Qc Planning Permission and Listed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Big City: Civic Symbolism and Scottish Nationalism’

Edinburgh Research Explorer ‘Big City: Civic Symbolism and Scottish Nationalism’ Citation for published version: Hearn, J 2003, '‘Big City: Civic Symbolism and Scottish Nationalism’', Scottish Affairs, vol. 42, pp. 57-82. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Scottish Affairs Publisher Rights Statement: © Hearn, J. (2003). ‘Big City: Civic Symbolism and Scottish Nationalism’. Scottish Affairs, 42, 57-82. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 30. Sep. 2021 1 BIG CITY: CIVIC SYMBOLISM AND SCOTTISH NATIONALISMi Jonathan Hearn, University of Edinburgh Published in: Scottish Affairs 42: 57-82, 2003 INTRODUCTION The stock symbols of Scotland and Scottishness are all too familiar. Living in Scotland one becomes almost numb to the drone of bagpipes and kilts, heather and kailyards, Nessie and Braveheart--the low hum of ‘cultural sub-nationalism’ that has so perturbed Tom Nairn (1977) and others over the years. As an American with an academic interest in Scotland and nationalismii I have often found myself straining to draw peoples’ attention away from these symbols and towards others I have found more telling for understanding contemporary nationalist demands in Scotland, such as Covenants and Claims of Right (Hearn 1998; 2000). -

Conservation Plan - December 2015

Royal High School Regent Road, Edinburgh Conservation Plan - December 2015 Simpson & Brown Contents Page 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 2.0 INTRODUCTION 7 2.1 Objectives of the Conservation Plan 7 2.2 Study Area 8 2.3 Heritage Designations 9 2.4 Structure of the Report 11 2.5 Adoption & Review 12 2.6 Other Studies 12 2.7 Limitations 12 2.8 Orientation 12 2.9 Project Team 12 2.10 Acknowledgements 12 2.11 Abbreviations 13 2.14 Building Names 13 3.0 UNDERSTANDING THE ROYAL HIGH SCHOOL 17 3.1 Introduction 17 3.2 Historical Background 17 3.3 The Royal High School – History and Meaning 25 3.4 Later Developments & Alterations 37 3.5 From School to Scottish Assembly 49 3.6 Summary Historical Development 63 3.7 Architects’ Biographies 65 3.8 Timeline of the Greek Revival 67 4.0 ASSESSMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 70 4.1 Introduction 70 4.2 Historical Significance 70 4.3 Architectural, Aesthetic and Artistic Significance 71 4.4 Social Significance 72 5.0 SUMMARY STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE 73 6.0 GRADING OF SIGNIFICANCE 74 6.1 Introduction 74 6.2 Graded Elements 78 7.0 CONSERVATION ISSUES & POLICIES 80 7.1 Introduction 80 7.2 Base Policies 81 7.3 Conservation Philosophy 81 7.4 Use of Surrounding Land 84 7.5 Specific Policies 85 7.6 Workmanship & Conservation Planning 86 7.7 Access & Interpretation 87 7.8 Recording & Research 88 7.9 Priority Repair Works & Maintenance 89 Royal High School, Edinburgh – Conservation Plan 1 8.0 APPENDICES 92 APPENDIX I - Listed Building Reports & Inventory Record 92 APPENDIX II - Illustrations at A3 100 2 Royal High School, Edinburgh – Conservation Plan 1.0 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Thomas Hamiltons’ Royal High School has been described as “arguably the most significant and accomplished Greek Revival building in the UK, it has claims to be amongst the finest on a worldwide stage.”1 This conservation plan for Thomas Hamilton’s Royal High School site is the third such report in ten years. -

Royal-High-School-Letter.Pdf

Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh By E-mail EH9 1SH Planning and Building Standards City of Edinburgh Council Direct Line: 0131 668 8089 Waverley Court Switchboard: 0131 668 8600 4 East Market Street [email protected] Edinburgh EH8 8BG Our ref: AMN/16/LA [email protected] Our Case ID: 201503563 Your ref: 15/03989/FUL & 15/03990/LBC & EIA-EDB053 30 September 2015 Dear Ms Parkes Town And Country Planning (Development Management Procedure) (Scotland) Regulations 2013 Proposed Calton Hill Hotel Development - Former Royal High School, 5-7 Regent Road, Edinburgh Thank you for your consultation which we received on 7 September. You have consulted us because you believe the development may affect: Setting of Category A Listed buildings: o Old Royal High School o St Andrew’s House o Regent Terrace o Burns’ Monument o Monuments on Calton Hill Setting of Scheduled Monuments: Holyrood Palace, Abbey and Gardens New Town Gardens – Historic Gardens/ Designed Landscape – Inventory Site (Calton Hill & Holyrood Palace Gardens & Regent Terrace Gardens) Outstanding Universal Value [‘OUV’] of Edinburgh Old and New Towns World Heritage Site [‘WHS’] In addition this letter responds to the associated Listed Building Consent application (15/03990/LBC) and the Environmental Statement (EIA-EDB053). We have previously objected to the planning permission affecting some of the above heritage assets because we do not consider it is possible to deliver a hotel of this scale on the site without unacceptable harm to the historic environment (our letter dated 17 September). This letter expands on that response and confirms both that we object to the planning application and that we cannot support the application for listed building consent. -

Scottish Ecological Design Association

© Scottish Ecological Design Association - www.seda.uk.net - The Scottish Ecological Design Association is a registered charity: SC020799 Designed by dotrun.co.uk S START WAVERLY STATION Start at Waverley Station and head up Waverley Steps to Princess Street, turn right and head up Calton Hill. 1 CALTON HILL Calton Hill is home the Scottish Government’s offices in St Andrew’s House on the steep southern slope of the hill – the Scottish Parliament Building and other notable buildings (Holyrood Palace) lying near the foot of the hill. The hill is also the location of several iconic monuments and buildings: the National Monument, the Nelson Monument, the Dugald Stewart Monument, the old Royal High School, the Robert Burns Monument, the Political Martyrs’ Monument and the City Observatory. The future of the derelict Old Royal High School is currently under debate. Rival proposals of a hotel by Hoskins Architects and a music school by Richard Murphy Architects have ignited fierce debate. Hopefully one of these proposals will give this impressive building a new lease of life. Collective Architecture has undertaken conservation work on the dome atop Calton Hill, enabling the structure to be opened to the public once again for art exhibitions and performances. The A-listed building is currently home to Collective gallery. From the summit of Calton Hill on a clear day you can see the wind turbines in Fife, contributing to the high percentage of renewable energy generated in Scotland. Also visible is the Scottish Parliament which achieved a BREEAM ‘Excellent’ rating when it was opened. It is heated by a combined heat and power plant and has 40m2 of solar panels. -

FINAL RELEASE: for Issue 9Am Wednesday September, 23 2015

FINAL RELEASE: For issue 9am Wednesday September, 23 2015 ROYAL HIGH SCHOOL TRUST MAKES STATEMENT OF INTENT TO EDINBURGH COUNCIL The Royal High School Preservation Trust (RHSPT) has declared its intent to pursue plans to move St Mary’s Music School into the famous neoclassical Thomas Hamilton buildings on Calton Hill. Backed by the philanthropic Dunard Fund, the Trust has made a formal legal offer to buy the iconic buildings and appointed renowned architect Richard Murphy OBE to develop designs to restore the site as a school, alongside conservation architects Simpson & Brown. With overwhelming community support for its initial plans following two public consultation events, the Trust now intends to submit a detailed and fully funded application to the City of Edinburgh Council as soon as possible. Making the announcement alongside Dr Kenneth Taylor, headteacher of St Mary’s Music School, William Gray Muir, the Chairman of the Trust, confirmed that a bid to purchase the Old Royal High School for £1.5m had been made, exceeding the value currently put on the buildings by the City of Edinburgh Council. This is a small part of a substantial funding pledge which has been made to the Trust to underwrite the cost of a conservation and conversion that respects the buildings’ original character, historic significance and location to secure their long-term future. The project will represent one of the single largest philanthropic arts gifts in modern Scottish history. He said: “The Old Royal High School buildings are crucial to the character of Edinburgh and part of the architectural heritage that attracts people to this wonderful city. -

Congress Programme Congress Online Conservation Challenges Inbuilt Heritage and Practices Current 28 2 -6NOVEMBER 2020 Th Biennial Congress #IICCONGRESS

McEwan Hall © University of Edinburgh 28th Biennial Congress Current Practices and Challenges in Built Heritage Conservation Online Congress Programme 2 - 6 NOVEMBER 2020 #IICCONGRESS Headline Partner and Title Sponsor: #IICCongress @iic_congress @International.Institute.for.Conservation International-institute-for-conservation- @iiconservation of-historic-and-artistic-works-the 2 IIC 28th Biennial Congress, Edinburgh 2020 #IICCongress 28th Biennial Congress Current Practices and Challenges in Built Heritage Conservation Online Contents IIC President’s Welcome 4 We’re delighted to see you online! 5 Congress Sponsors 6 Local Organising Partners 7 IIC, Our Story and Our Purpose 8 Awards and Prizes at IIC Congress 10 The Forbes Prize Lecture The Keck Award Posters Prizes Congress Committees 15 Congress Technical Programme 16 Getty Grant Recipients and Getty Leadership Workshop 23 Posters 24 Student Posters 28 IIC Dialogue 30 Congress Exhibition Sessions 32 Virtual Tours and Excursions 39 IIC Council, Officers and Staff 46 Current Practices and Challenges in Built Heritage Conservation 3 IIC President’s Welcome Dear Friends IIC Congresses are renowned for the quality of their papers, but also for the Welcome to IIC’s first fully online Congress. quality of the event itself, providing an ideal Our Congresses are always a major event forum for the exchange of ideas and the in the conservation calendar, but our development of conservator networks – we programme for this year stands out for will continue to deliver these objectives its breadth of subject matter, bringing online. I want to pay tribute to Sarah in new insights from a range of related Stannage, Executive Director of IIC, and to fields. -

Minute's of Fairmilehead Community Council Tuesday 3Rd October, 2006

Fairmilehead Community Council meeting held on Tuesday 4 October 2016 in Fairmilehead Parish Church Present: Dennis Williams (Chair); Norman Tinlin (Secretary); Fiona Simon (Treasurer); Colin Anderson; Johanna Carrie; Barbara Dick (Buckstone Association); Carol Lonie (Buckstone Youth); Ex Officio: Councillor Aitken; WPC Sonja Kaiser; 16 members of the public Apologies: Andy Lippok; Fraser Simon; Councillors Lewis & Rust; Ian Murray MP; Gordon Lindhurst MSP; George Symonds, Tom Strathdee; Douglas Grossart Councillor Aitken was in the Chair until Item 5. 1. Police Report WPC Kaiser was detained due to an operational matter so her report was presented later on in the meeting but for consistency is in the normal order on the agenda: Prior to her arrival the Secretary handed out a copy of a response Gordon Lindhurst MSP had received from the Divisional Commander following on from points raised at the previous meeting. This response is reproduced at Appendix A. It was also decided that a monthly crime prevention tip would be put on the website, noticeboard and in the minutes. WPC Kaiser gave her report for September. Community Officers are now permitted to issue a copy of their report to the meeting. The report is attached at the end of the minutes. WPC Kaiser also said that there had been complaints about Mounthooly Loan being used as a park and ride but all vehicles were parked legitimately. Also a complaint had been received about a large quantity of builders rubble having been deposited o the road way there. Should you wish to contact the Community Policing Team, you can do so by email at [email protected] or by telephoning the new national non-emergency number 101. -

Adventurestake You?

WHERE WILL YOUR fringe ADVENTURES TAKE YOU? CB-34423-Fringe-Programme header 420x45-Aw-DI.indd 1 26/04/2016 17:21 1 2 3 4 5 6 500m Beaverhall Road 83 120 J8 Pilrig Street McDonald Road Inverleith Row 2k Logie Green Road Logie Mill Cycle path Edinburgh Festival Fringe Box Edinburgh Art Festival A15 1 446 Arboretum Place Office and Shop (E5) 369 Steps 370 2 Fringe Central (F5) F Edinburgh Festival Fringe 28 Public walkway Dryden Street A Spey Terrace Railway station Virgin Money Fringe Edinburgh Festival Fringe 10 FMcDonald Place on the Royalres Mile (E5) with Ticket Collection Point C t Car parking n McDonald Shaw’s o Street Street m Edinburgh International e Virgin Moneyr Fringe a Toilets l B 55 Gdns Bellevue Shaw’s C Book Festival on The Mound W(D4) Annandale St Place Inverleith Terrace VisitScotland Broughton Road ClaremoVirginnt Money Half McDonald Road Gro M Edinburgh Mela Information Centre H Priceve Hut (D4) k B anonmills t C n Edinburgh International o Fringe EastTicket Claremont Street Canon St m Rodney St TCre Bellevue Road i 100m B la Collection Point HopetounFestival Street e C l l e Bellevue Street East Fettes Avenue e v 282 c u TransportMelgund for Edinburgh Edinburgh Jazz a e t r Annandale Street en r c TS Terrace J s e T and Blues Festival re T e Travelshop C rr n a n o Place c u e 500m Glenogle Road d to n Green Street e a r See inset below The Royal Edinburghp Cornwallis Edinburgh Bus Tours o B Eyre Pl BUS T Saxe-Coburg Military Tattoo H 195 for Leith venues Bellevue bank A24 600m Place Summer- B Brunswick Street e Saxe-Coburg -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. ‘Save Our Old Town’: Engaging developer-led masterplanning through community renewal in Edinburgh Christa B. Tooley PhD in Social Anthropology The University of Edinburgh 2012 (72,440 words) Declaration I declare that the work which has produced this thesis is entirely my own. This thesis represents my own original composition, which has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification. __________________________________________________ Christa B. Tooley Abstract Through uneven processes of planning by a multiplicity of participants, Edinburgh’s built environment continues to emerge as the product of many competing strategies and projects of development. The 2005 proposal of a dramatic new development intended for an area of the city’s Old Town represents one such project in which many powerful municipal and commercial institutions are invested. -

Risks in Political Projects the New Scottish Parliament Building

5/5/10 Risks in Political Projects The New Scottish Parliament Building Case Study Published here August 2010 Note: The Issues for Discussion at the end of this case study may require research on the Internet. Introduction Scotland's new Parliament sits at the foot of Edinburgh's famous Royal Mile in front of the spectacular Holyrood Park and Salisbury Crags as shown in Figure 1. Figure 1: The new Scottish Parliament Building at Holyrood, Scotland designed by the Catalan architect Enric Miralles and opened in October 20041 Constructed from a mixture of steel, oak, and granite, the complex building has been hailed as one of the most innovative designs in Britain today. Construction of the building commenced in June 1999 and the Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs) held their first debate in the new building on Tuesday, September 7, 2004. The formal opening by Queen Elizabeth took place on October 9, 2004. Enric Miralles, the Catalan architect who designed the building, died before its completion.2 From 1999 until the opening of the new building in 2004, committee rooms and the debating chamber of the Scottish Parliament were housed in the General Assembly Hall of the Church of Scotland located on The Mound in Edinburgh. Office and administrative accommodation in support of the Parliament were provided in buildings leased from the City of Edinburgh Council. The new Scottish Parliament Building brought together these different elements into one purpose built parliamentary complex, housing 129 MSPs and more than 1,000 staff and civil servants. Comprising an area of 1.6 ha (4 acres), with a perimeter of 480 m (1570 ft), the Scottish Parliament building is located 1 km (0.6 mi) east of Edinburgh city centre on the edge of the Old Town. -

1 2 3 4 5 6 a B C D E F

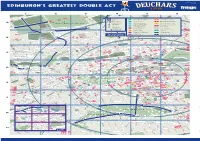

CALEDONIAN DEUCHARS IPA FRINGE PROGRAMME MAP HEADER - 420 x 45mm high 1 2 3 4 5 6 84 Beaverhall Road J8 Pilrig Street 120 McDonald Road Inverleith Row 369 Logie Green Road Logie Mill A15 Cycle Path 1 Edinburgh Festival Fringe Box Edinburgh Art Festival Arboretum Place 193 Office and Shop (E5) 446 Steps 2k 380 2 Fringe Central (F5) F Edinburgh Festival Fringe 28 Public Walkway Dryden Street A Spey Terrace Railway Station Virgin Money Fringe Edinburgh Festival Fringe 10 FMcDonald Place on the Royalres Mile (E5) with Ticket Collection Point C t Car Parking n McDonald Shaw’s o Street Street m Edinburgh International e Virgin Moneyr Fringe a Toilets l B 371 55 Gdns Bellevue Shaw’s C Book Festival on the Mound (D4)W Annandale St Place Inverleith Terrace VisitScotland Broughton Road ClaremoVirginnt Money Half McDonald Road Gro M Edinburgh Mela 50m Information Centre H Priceve Hut (D4) k 100m B 103 onm t an ills 300m C n Edinburgh International o Fringe EastTicket Claremont Street 282 Canon St m Rodney St TCre Bellevue Road i B la Collection Point HopetounFestival Street 375 e C l l e Bellevue Street East Fettes Avenue e v c u TransportMelgund for Edinburgh Edinburgh Jazz a e t r Annandale Street en r c TS Terrace J s e T and Blues Festival re T e Travelshop C rra n n o Place ce u Glenogle Road to 500m nd Green Street e a r See inset below p 207 Cornwallis Edinburgh Bus Tours o B Eyre Pl BUS T Royal Edinburgh Military Tattoo Saxe-Coburg H 195 for Leith Venues Bellevue 600m bank Place Summer- A23 B Brunswick Street e Saxe-Coburg St 70 317 ll Bridge -

Edinburgh Old Town Association Newsletter

Edinburgh Old Town Association Newsletter September 2015 Who knows what the weather will be doing by the time you read this. Based on what we have had so far this year it could be almost anything. One thing that can be safely predicted is that the festival season will soon be in full flow again. And another is that for the foreseeable future cranes will continue to be a feature of the Old Town skyline with major building projects underway and more in the pipeline. This edition’s photo-essay looks at a few examples and also exposes witches’ knickers. We also consider a location just outside the Old Town area where development could have a visual impact on us: the old Royal High School. We also mention a few changes and developments around the Old Town which you may or may not have spotted. In our last edition there was a piece about the riot around the Tron Kirk at Hogmanay 1811. Audrey Deakin of the Scottish Historic Buildings Trust tells us that there is a surprising link between this story and Riddle’s Court. The rioters would have been tried at the Edinburgh Police Court, which from 1805 was in Riddle’s Court – one of the many uses to which the building has been put. Now the contract is just about to be let for the building’s latest transformation - into the Patrick Geddes Centre. We hope to have more news of this in a future newsletter. Also in the last newsletter was a mention of the fascinating introduction to treasures from the Central Library collection which Library Development Officer Karen O’Brien gave us at our AGM in March.