The Regular and the Secular: Plympton Priory and Its Connections to the Secular Clergy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book IV – Function of the Church: Part I – the Sacraments

The Sacraments The Catholic Church recognizes the existence of Seven Sacraments instituted by the Lord. They are: Sacraments of Christian Initiation: Baptism, Confirmation, and the Eucharist Sacraments of Healing: Penance (Reconciliation) and Anointing of the Sick Sacraments at the Service of Communion: Holy Orders and Matrimony Code of Cannon Law: Book IV - Function of the Church: Part I - The Sacraments The Sacraments (Code of Canon Law; Cann. 840-848) Can. 840 The sacraments of the New Testament were instituted by Christ the Lord and entrusted to the Church. As actions of Christ and the Church, they are signs and means which express and strengthen the faith, render worship to God, and effect the sanctification of humanity and thus contribute in the greatest way to establish, strengthen, and manifest ecclesiastical communion. Accordingly, in the celebration of the sacraments the sacred ministers and the other members of the Christian faithful must use the greatest veneration and necessary diligence. Can. 841 Since the sacraments are the same for the whole Church and belong to the divine deposit, it is only for the supreme authority of the Church to approve or define the requirements for their validity; it is for the same or another competent authority according to the norm of can. 838 §§3 and 4 (Can. 838 §3. It pertains to the conferences of bishops to prepare and publish, after the prior review of the Holy See, translations of liturgical books in vernacular languages, adapted appropriately within the limits defined in the liturgical books themselves. §4. Within the limits of his competence, it pertains to the diocesan bishop in the Church entrusted to him to issue liturgical norms which bind everyone.) to decide what pertains to their licit celebration, administration, and reception and to the order to be observed in their celebration. -

1 Introduction 2 the New Religious Orders 3 the Council of Trent And

NOTES 1 Introduction I. This term designates first of all the act of 'confessing' or professing a par ticular faith; secondly, it indicates the content of that which is confessed or professed, as in the Augsburg Confession; finally then it comes to mean the group that confesses this particular content, the church or 'confession'. 2 The New Religious Orders I. The terms 'order' and 'congregation' in this period were not always clear. An order usually meant solemn vows, varying degrees of exemption from the local bishop, acceptance of one of the major rules (Benedictine, Augustinian, Franciscan), and for women cloister.A congregation indicated simple vows and usually subordination to local diocesan authority. A con fraternity usually designated an association of lay people, sometimes including clerics, organized under a set of rules , to foster their common religious life and usually to undertake some common apostolic work. In some cases confraternities evolved into congregations, as was the case with many of the third orders, and congregations evolved into orders. 2. There is no effort here to list all the new orders and congregations that appeared in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. 3. An English translation of Regimini Militantis Ecclesiae, the papal bull of 27 September 1540 establishing the Society ofJesus, is found in John Olin, The Catholic Reformation: Savonarola to Ignatius Loyola: Reform in the Church, /495-1540 (New York: Harper and Row, 1969), pp. 203-8. 3 The Council of Trent and the Papacy I. The Complete Works of Montaigne: Essays, Travel journal, Letters, trans. Donald M. Frame (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1957), p. -

Water, Water ..Everywhere!

February 2016 Number 124 LOCAL EVENTS NEWS FEATURES INFORMATION Water, Water ..everywhere! Photo at Higher Mill Bridge - Sylvia Preece Photos in village centre - Dick Nicklin S LISTING DE GUI & When n, Where What’s O vy Parish in Peter Ta NEW PUBLIC EMERGENCY DEFIBRILLATOR installed outside Village Hall - see pages 6-7 for details Avant nous, le deluge! February Wed 17th 10 - 10.30am Mobile Library Van calls, Church Lane 8.00pm Quiz Night, Peter Tavy Inn. Thurs 18th 7.30pm St. Peter’s PCC meeting, Edgecombe Sun 21st 4.00pm Joint Family Service, Methodist Church Tues 23rd 7.30pm Flower Festival planning meeting, Village Hall Fri 26th 7 - 9pm Youth Club, Methodist Church Sat 27th 7.30pm Quiz Night for Friends of St. Peter’s, Village Hall March Thurs 3rd 4.30pm Messy Church, Methodist Church Sat 5th 7.30pm BINGO night, Village Hall Sun 6th Mothering Sunday Thurs 10th 12 - 1.30pm Soup & Dessert Lunches, Methodist Church Eve “Locals' Evening" at the Peter Tavy Inn. Sat 12th 10 - 12noon Daf fodil Cof fee Morning, Manor Fm, Cuddlipptown 7.30pm “Jim Causley” - VIA concert, Village Hall. Wed 16th 10 - 10.30am Mobile Library Van calls, Church Lane 8.00pm Quiz Night, Peter Tavy Inn. Fri 18 th 7 - 9pm Youth Club, Methodist Church Sun 20th 3.00pm Palm Sunday - Joint Family Service, St. Peter’s Church Thurs 24th tbc Maundy Thursday Service, Methodist Church Fri 25th tbc Good Friday Service, St Peter’s Church Sun 27th 9.30am Easter Sunday: Communion, St. Peter’s Church 4.00pm Easter Sunday Service, Methodist Church April Sun 3rd 6.30pm Start of summer time services, Methodist Church Thurs 7th 4.30pm Messy Church, Methodist Church 7.00pm St. -

Königreichs Zur Abgrenzung Der Der Kommission in Übereinstimmung

19 . 5 . 75 Amtsblatt der Europäischen Gemeinschaften Nr . L 128/23 1 RICHTLINIE DES RATES vom 28 . April 1975 betreffend das Gemeinschaftsverzeichnis der benachteiligten landwirtschaftlichen Gebiete im Sinne der Richtlinie 75/268/EWG (Vereinigtes Königreich ) (75/276/EWG ) DER RAT DER EUROPAISCHEN 1973 nach Abzug der direkten Beihilfen, der hill GEMEINSCHAFTEN — production grants). gestützt auf den Vertrag zur Gründung der Euro Als Merkmal für die in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 Buch päischen Wirtschaftsgemeinschaft, stabe c ) der Richtlinie 75/268/EWG genannte ge ringe Bevölkerungsdichte wird eine Bevölkerungs gestützt auf die Richtlinie 75/268/EWG des Rates ziffer von höchstens 36 Einwohnern je km2 zugrunde vom 28 . April 1975 über die Landwirtschaft in Berg gelegt ( nationaler Mittelwert 228 , Mittelwert in der gebieten und in bestimmten benachteiligten Gebie Gemeinschaft 168 Einwohner je km2 ). Der Mindest ten (*), insbesondere auf Artikel 2 Absatz 2, anteil der landwirtschaftlichen Erwerbspersonen an der gesamten Erwerbsbevölkerung beträgt 19 % auf Vorschlag der Kommission, ( nationaler Mittelwert 3,08 % , Mittelwert in der Gemeinschaft 9,58 % ). nach Stellungnahme des Europäischen Parlaments , Eigenart und Niveau der vorstehend genannten nach Stellungnahme des Wirtschafts- und Sozialaus Merkmale, die von der Regierung des Vereinigten schusses (2 ), Königreichs zur Abgrenzung der der Kommission mitgeteilten Gebiete herangezogen wurden, ent sprechen den Merkmalen der in Artikel 3 Absatz 4 in Erwägung nachstehender Gründe : der Richtlinie -

'Libera Nos Domine'?: the Vicars Apostolic and the Suppressed

‘Libera nos Domine’? 81 Chapter 4 ‘Libera nos Domine’?: The Vicars Apostolic and the Suppressed/Restored English Province of the Society of Jesus Thomas M. McCoog, SJ It would have been much to the interests of the Church if her history had not included the story of such difficulties as those which are the subject of this chapter. Her internal dissensions, whether on a large or small scale, bear the same relation to the evils inflicted on her from without, as diseases do to wounds won in honourable fight. Thus did Edwin H. Burton open the chapter ‘The Difficulties between the Vicars Apostolic and the Regulars’ in his work on Bishop Challoner.1 The absence of such opposition may have made the history of the post-Reforma- tion Roman Catholic Church in England more edifying, but surely would also have deprived subsequent scholars of fascinating material for dissertations and monographs. In his doctoral thesis Eamon Duffy remarked that, although tension between Jesuits and seculars was less than in previous centuries, ‘the bitterness … which remained was all pervasive … No Catholic in England escaped untouched’.2 Basil Hemphill, having noted that ‘most unfortunate jealousies persisted between the secular and the regular clergy … and with an intensity which seems incredible to us today’, considered their explication essential if history wished to be truthful ‘and if it be not truthful it is of no use at all’.3 A brief overview of uneasy, volatile and tense relations between Jesuits and secular clergy in post-Reformation England will contextualize the eigh- teenth-century problem. 1 Edwin H. -

The Church in the Post-Tridentine and Early Modern Eras

Provided by the author(s) and NUI Galway in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite the published version when available. Title The Church in the Tridentine and Early Modern Eras Author(s) Forrestal, Alison Publication Date 2008 Publication Forrestal, Alison, The Church in the Tridentine and Early Information Modern Eras In: Mannion, G., & Mudge, L.S. (2008). The Routledge Companion to the Christian Church: Routledge. Publisher Routledge Link to publisher's https://www.routledge.com/The-Routledge-Companion-to-the- version Christian-Church/Mannion-Mudge/p/book/9780415567688 Item record http://hdl.handle.net/10379/6531 Downloaded 2021-09-26T22:08:25Z Some rights reserved. For more information, please see the item record link above. The Church in the Tridentine and Early Modern Eras Introduction: The Roots of Reform in the Sixteenth Century The early modern period stands out as one of the most creative in the history of the Christian church. While the Reformation proved viciously divisive, it also engendered theological and devotional initiatives that, over time and despite resistance, ultimately transformed the conventions of ecclesiology, ministry, apostolate, worship and piety. Simultaneously, the Catholic church, in particular, underwent profound shifts in devotion and theological thought that were only partially the product of the shock induced by the Reformation and at best only indirectly influenced by pressure from Protestant Reformers. Yet despite the pre-1517 antecedents of reformatio, and the reforming objectives of the Catholic Council of Trent (1545-7, 1551-2, 1562-3), the concept of church reform was effectively appropriated by Protestants from the sixteenth century onwards. Protestant churchmen claimed with assurance that they and the Reformation that they instigated sought the church’s 'reform in faith and practice, in head and members’. -

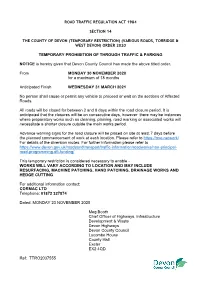

Various Roads, Torridge & West Devon

ROAD TRAFFIC REGULATION ACT 1984 SECTION 14 THE COUNTY OF DEVON (TEMPORARY RESTRICTION) (VARIOUS ROADS, TORRIDGE & WEST DEVON) ORDER 2020 TEMPORARY PROHIBITION OF THROUGH TRAFFIC & PARKING NOTICE is hereby given that Devon County Council has made the above titled order. From MONDAY 30 NOVEMBER 2020 for a maximum of 18 months Anticipated Finish WEDNESDAY 31 MARCH 2021 No person shall cause or permit any vehicle to proceed or wait on the sections of Affected Roads. All roads will be closed for between 2 and 8 days within the road closure period. It is anticipated that the closures will be on consecutive days, however there may be instances where preparatory works such as cleaning, plaining, road marking or associated works will necessitate a shorter closure outside the main works period. Advance warning signs for the road closure will be placed on site at least 7 days before the planned commencement of work at each location. Please refer to https://one.network/ For details of the diversion routes. For further information please refer to https://www.devon.gov.uk/roadsandtransport/traffic-information/roadworks/non-principal- road-programming-dft-funding/ This temporary restriction is considered necessary to enable - WORKS WILL VARY ACCORDING TO LOCATION AND MAY INCLUDE RESURFACING, MACHINE PATCHING, HAND PATCHING, DRAINAGE WORKS AND HEDGE CUTTING For additional information contact: CORMAC LTD Telephone: 01872 327874 Dated: MONDAY 23 NOVEMBER 2020 Meg Booth Chief Officer of Highways, Infrastructure Development & Waste Devon Highways Devon County Council Lucombe House County Hall Exeter EX2 4QD Ref: TTRO2037555 There were several sites which were not completed within the first anticipated end date. -

Newsletter No.7 Little Short of Helpers, and We March 2015 Free Couldn't Put on All the Activities We Had Planned

Sun 1 Nov 2015 Following another successful Bonfire Night last November, we're already making arrangements for this year. Last year we found we were a Newsletter No.7 little short of helpers, and we March 2015 Free couldn't put on all the activities we had planned. We need to get more people involved this year to Welcome to this issue of our Newsletter. If you want to contact us make sure it's the best event it you'll find our details on the back page. Happy reading. can possibly be, so whether your forté is coming up with ideas, organising other people, moving An exciting week for off at Legoland on the way tables or providing general Primary School Pupils home. helping on the night, we'd love you to be a part of the team. Most Key Stage 2 children at the There will be a celebration primary school will be going to concert on 17 March at the The Jubilee Group and the London in early March to take Coronation Hall so that the Trustees of the Recreation part in the Voice in a Million children can share their singing Ground are forming a Bonfire charity concert at Wembley with the parents and sponsors. Night Working Group - Stadium, along with around Meanwhile all those who are Bonfire Night 7,000 other children. not going to London will be part Meeting of a Working Group Whilst in London they will be of a really exciting African Arts Tues 31 March, 7.30pm visiting the Science Museum and Week, with lots of dancing and The Royal Standard St. -

Fiestas and Fervor: Religious Life and Catholic Enlightenment in the Diocese of Barcelona, 1766-1775

FIESTAS AND FERVOR: RELIGIOUS LIFE AND CATHOLIC ENLIGHTENMENT IN THE DIOCESE OF BARCELONA, 1766-1775 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrea J. Smidt, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Dale K. Van Kley, Adviser Professor N. Geoffrey Parker Professor Kenneth J. Andrien ____________________ Adviser History Graduate Program ABSTRACT The Enlightenment, or the "Age of Reason," had a profound impact on eighteenth-century Europe, especially on its religion, producing both outright atheism and powerful movements of religious reform within the Church. The former—culminating in the French Revolution—has attracted many scholars; the latter has been relatively neglected. By looking at "enlightened" attempts to reform popular religious practices in Spain, my project examines the religious fervor of people whose story usually escapes historical attention. "Fiestas and Fervor" reveals the capacity of the Enlightenment to reform the Catholicism of ordinary Spaniards, examining how enlightened or Reform Catholicism affected popular piety in the diocese of Barcelona. This study focuses on the efforts of an exceptional figure of Reform Catholicism and Enlightenment Spain—Josep Climent i Avinent, Bishop of Barcelona from 1766- 1775. The program of “Enlightenment” as sponsored by the Spanish monarchy was one that did not question the Catholic faith and that championed economic progress and the advancement of the sciences, primarily benefiting the elite of Spanish society. In this context, Climent is noteworthy not only because his idea of “Catholic Enlightenment” opposed that sponsored by the Spanish monarchy but also because his was one that implicitly condemned the present hierarchy of the Catholic Church and explicitly ii advocated popular enlightenment and the creation of a more independent “public sphere” in Spain by means of increased literacy and education of the masses. -

06 January 2017 Reports

NPA/DM/17/001 DARTMOOR NATIONAL PARK AUTHORITY DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT COMMITTEE 06 January 2017 SITE INSPECTIONS Report of the Head of Planning 1 Application No: 0315/16 District/Borough: West Devon Borough Application Type: Full Planning Permission Parish: Peter Tavy Grid Ref: SX513776 Officer: Jo Burgess Proposal: New dwelling (revised re-design of existing planning consent 0270/14) on site of former garage Location: Peter Tavy Garage, Peter Tavy Applicant: Mr G Goddard Recommendation: That permission be GRANTED Condition(s) 1. The development hereby permitted shall be begun before the expiration of three years from the date of this permission. 2. Notwithstanding the provisions of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) Order 2015 or any Order revoking and re-enacting that Order with or without modification, no material alterations to the external appearance of the dwelling shall be carried out and no extension, building, enclosure, structure, erection, hard surface, raising of the land, swimming or other pool shall be constructed or erected in or around the curtilage of the dwelling hereby permitted, and no windows or roof lights other than those expressly authorised by this permission shall be created, formed or installed, without the prior written authorisation of the Local Planning Authority. 3. The finished floor levels of the dwelling shall be no lower than 163.790mAOD. Written confirmation of the finished floor level shall be provided in writing to the Local Planning Authority prior to any work being carried out to erect the walls of the dwelling. 4. The roof of the main dwelling and lean-to hereby approved shall be covered in natural slate, sample(s) of which shall be submitted to the Local Planning Authority for approval prior to the commencement of any roofing work. -

![On the Part of the Clergy [C.278] and of the Laity [C. 1374]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3482/on-the-part-of-the-clergy-c-278-and-of-the-laity-c-1374-1073482.webp)

On the Part of the Clergy [C.278] and of the Laity [C. 1374]

The Right to Associate-- on the Part of the Clergy [C.278] and of the Laity [C. 1374] Adolfo N. Dacanáy¨ Abstract: This short study on the right to associate in canon law is divided into three unequal parts: (1) the right of clerics affirmed in C. 278; and (2) the “restriction” of this right of the Catholic laity by C. 1374 (masonry); and (3) a footnote on masonry in the Philippines. Keywords: Code of Canon Law • Right to Associate • Clergy • Laity • Masonry 1. The Right of Clerics to Associate [C. 278] The three paragraphs of the canon concern the right of the secular clergy to associate and the limits of this right: (a) the secular clerics have the right to associate with others to pursue purposes consistent with the clerical state; (b) in particular, associations approved by competent authority which fosters holiness in the exercise of the ministry are to be esteemed; (c) clerics are to refrain from establishing or participating in associa- tions whose purposes or activities cannot be reconciled with the obligations of the clerical state. ¨ Fr. Adolfo N. Dacanáy, S.J., entered the Society of Jesus in 1977 and was ordained to the priesthood in 1983. He obtained his doctorate in Canon Law from the Pontifical Gregorian University (Rome) in 1989. He teaches undergraduate and graduate theology at the Ateneo de Manila University, Canon Law on the Sacraments at the Don Bosco School of Theology (Parañaque), and serves as a judge in the ecclesiastical tribunals of the Archdiocese of Manila, and of the Dioceses of Pasig and Lucena. -

NRA C V M Davies Environmental Protection National Rlvara a Uthority Manager South Waat Rag Ion REGIONAL HATER QUALITY MONITORING and SURVEILLANCE PROGRAMME for 1993

Environmental Protection Draft Report REGIONAL WATER QUALITY MONITORING AND SURVEILLANCE PROGRAMME FOR 1993 BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT OF RIVERS February 1993 FWS/93/001 Author: Dr JAD Murray-Bligh Assistant Scientist (Freshwater Biology) NRA C V M Davies Environmental Protection National Rlvara A uthority Manager South Waat Rag Ion REGIONAL HATER QUALITY MONITORING AND SURVEILLANCE PROGRAMME FOR 1993 BIOLOGICAL QUALITY ASSESSMENT OF RIVERS INTERNAL REPORT FWS/93/001 SUMMARY This report describes the biological river quality monitoring programme to be undertaken by NRA South West Region in 1993. 515 sites are to be surveyed during 1993. The regional programme is completed in two years and comprises approximately 950 sites covering 4230 km of river and 27 km of canal. Half the catchments are surveyed in any one year. The couplete two-year programme matches the reaches monitored in the chemical monitoring programme. Additional sites are included so that all reaches that were assigned River Quality Objectives in the Asset Management Plan produced in 1989 are monitored. The following catchments are to be surveyed in full in 1993: Lim Exe Teign Dart Gar a Avon Seaton Looe Fowey (lower sub-catchment only) Par Crinnis St Austell South Cornwall Streams Fal Helford Lizard Streams Land's End Streams Hayle Red and Coastal Streams Gannel Valency and Coastal Streams Strat/Neet Hartland Streams North Devon Coastal Streams Lyn Twenty-two key sites throughout the region are sampled every year, to assess annual changes. Three sites are solely to monitor the impact of discharges from mushroom farms and are not used for river quality classification purposes.