Delphine Ugalde: Defying Gender Norms Both on and Off Thet S Age in 19Th Century Paris Michael T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alice Pike Barney Papers and Related Material, Circa 1889-1995

Alice Pike Barney Papers and Related Material, circa 1889-1995 Finding aid prepared by Smithsonian Institution Archives Smithsonian Institution Archives Washington, D.C. Contact us at [email protected] Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Historical Note.................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction....................................................................................................................... 2 Descriptive Entry.............................................................................................................. 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: ALICE PIKE BARNEY AUTOBIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION............... 5 Series 2: THEATRICAL PRODUCTIONS: SCRIPTS............................................... 6 Series 3: THEATRICAL PRODUCTIONS: SELECTED SCENES AND ROLES.................................................................................................................... 11 Series 4: NON-THEATRICAL, LITERARY MANUSCRIPTS.................................. 12 Series 5: MUSICAL -

Leihmaterial Bote & Bock

Leihmaterial Bote & Bock - Stand: November 2015 - Komponist / Titel Instrumentation Komp. / Dauer Aa, Michel van der 2 After Life B 2S,M,A,2Ba; 2005-06/ 95' Oper nach dem Film von Hirokazu Kore-Eda 0.1.1.BKl.0-0.1.0.1-Org(=Cemb)-Str(3.3.3.2.2); 2009 elektr Soundtrack; Videoprojektionen 1 The Book of DisquietB 1.0.1.1-0.1.0.0-Perc(1): 2008 75' Musiktheater für Schauspieler, Ensemble und Film Vib/Glsp/3Metallstücke/Cabasa/Maracas/Egg Shaker/ 4Chin.Tomt/grTr/Bambusglocken/Ratsche/Peitsche(mi)/ HlzBl(ti)/2Logdrum/Tri(ho)/2hgBe-4Vl.3Va.2Vc.Kb- Soundtrack(Laptop,1Spieler)-Film(2Bildschirme) 0 Here [enclosed] B 0.0.1.1-0.1.1.0-Perc(1)-Str(6.6.6.4.2)- 2003 17' für Kammerorchester und Soundtrack Soundtrack(Laptop, 1Spieler); Theaterobjekt K Here [in circles] B Kl.BKl.Trp-Perc(1)-Str(1.1.1.1.1); 2002 15' für Sopran und Ensemble kl Kassetten-Rekorder (z.B. Sony TCM-939) 0 Here [to be found]B 0.0.1.1-0.1.1.0-Perc(1)-Str(6.6.6.4.2)- 2001 18' für Sopran, Kammerorchester und Soundtrack Soundtrack(Laptop, 1 Spieler) Here Trilogy B 2001-03 50' siehe unter Here [enclosed], Here [in circles], Here [to be found] F Hysteresis B Fg-Trp-Perc(1)-Str*; Soundtrack(Laptop,1 Spieler); 2013 17' für Solo-Klarinette, Ensemble und Soundtrack *Streicher: 1.0.1.1.1 (alle vertärkt) oder 4.0.3.2.1 oder 6.0.5.4.2; Kb mit tiefer C-Saite 2 Imprint B 2Ob-Cemb-Str(4.4.3.2.1); 2005 14' für Barock-Orchester Portativ-Orgel zu spielen vom Solo-Violinisten; Historische Instrumente (415 Hz Stimmung) oder moderne Instrumente in Barock-Manier gespielt 1 Mask B 1.0.1.0-1.1.1.0-Perc(1)-Str(1.1.1.1.1)- -

Portraits of a Brother and Sister of the Luppé Family (A Pair) Oil on Panel 9¼ X 6 In

Louise Abbéma (1927 1853 - ) Portraits of a brother and sister of the Luppé family (a pair) oil on panel 9¼ x 6 in. (23.5 x 15.2 cm.) Louise Abbéma was a French painter and designer, born in Etampes. She began painting in her early teens, and studied under such notables of the period as Charles Joshua Chaplin, Jean-Jacques Henner and Carolus-Duran. She first received recognition for her work at 23 when she painted a portrait of Sarah Bernhardt, her life-long friend and, many believe, her lover. She excelled at portraiture and flower painting equally at ease in all mediums and also painted panels and murals which adorned the Paris Town Hall, the Paris Opera House, numerous theatres including the "Theatre Sarah Bernhardt", and the "Palace of the Colonial Governor" at Dakar, Senegal. She was a regular exhibitor at the Paris Salon, where she received an honorable mention for her panels in 1881. Abbéma was also among the female artists whose works were exhibited in the Women's Building at the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. A bust Sarah Bernhardt sculpted of Abbéma was also exhibited at the exposition. Her most remarkable work is, perhaps, Le Déjeuner dans la serre, in the Pau Museum, not unworthy of comparison with her Impressionist friends, Bazille and Manet. The characteristics of her painterly style are apparent in this small pair of typically fashionable sitters, a brother and sister of the Luppé family. Among the many honors conferred upon Abbéma was nomination as official painter of the Third Republic. -

French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed As a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1971 French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth. John G. Cale Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Cale, John G., "French Secular Music in Saint-Domingue (1750-1795) Viewed as a Factor in America's Musical Growth." (1971). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 2112. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/2112 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 72-17,750 CALE, John G., 1922- FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH. The Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College;, Ph.D., 1971 Music I University Microfilms, A XEROX Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FRENCH SECULAR MUSIC IN SAINT-DOMINGUE (1750-1795) VIEWED AS A FACTOR IN AMERICA'S MUSICAL GROWTH A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The School of Music by John G. Cale B.M., Louisiana State University, 1943 M.A., University of Michigan, 1949 December, 1971 PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. -

Musicien. 1 PRÉSENTATION

Offenbach, Jacques - musicien. 1 PRÉSENTATION Offenbach, Jacques (1819-1880), violoncelliste et compositeur allemand, naturalisé français (1860), considéré comme le fondateur de l’opérette. Né à Cologne, dans la famille d’un cantor de synagogue et violoniste, Jacques (en réalité Jakob) Offenbach étudie le violon, puis le violoncelle dès l'âge de neuf ans. En 1833, son père l’amène à Paris et réussit à le faire admettre au Conservatoire, malgré ses origines étrangères. Il n’y reste qu’un an, devient violoncelliste à l'orchestre de l'Opéra-Comique, qu’il quitte dès 1835 pour une carrière soliste de musique de chambre. En 1850, il est appelé à diriger la musique à la Comédie-Française. Compositeur depuis l’enfance, il a pris quelques leçons avec Jacques Halévy en 1835, et livré régulièrement des mélodies ou pièces courtes comme l’Alcôve qui remporte, en 1847, un grand succès. Il espère être joué à l’Opéra-Comique. 2 LA GRANDE PÉRIODE CRÉATRICE En attendant, il fonde en 1855 son propre théâtre, les Bouffes-Parisiens, et rencontre le succès dès le premier spectacle, grâce aux Deux aveugles. Directeur jusqu’en 1861, compositeur, chef d’orchestre, metteur en scène, il livre continûment, sur des livrets de Ludovic Halévy, auquel se joint ensuite Henri Meilhac, des ouvrages nouveaux, parmi lesquels Orphée aux enfers (1858), la Chanson de Fortunio (1861), la Belle Hélène (1864), Barbe-Bleue (1866), la Vie parisienne (1866), la Grande- Duchesse de Gérolstein (1867), la Périchole (1868). Il triomphe aussi à l’étranger, surtout à Vienne. Après la chute du Second Empire, bien que la faveur du public soit moindre en raison de l’évolution du goût et de la présence de nouveaux auteurs comme Charles Lecocq, elle se maintient toutefois, tant lors de reprises, comme la Belle Hélène en 1876, que pour des créations comme Madame Favart ou la Fille du Tambour-major (1879), mais n’empêche pas la faillite, en 1875, de son théâtre de la Gaîté-Lyrique, fondé en 1873. -

Style in Singing

ri ht 1 9 1 1 C opy g , SC H IRMER By G . 22670 PREFA TO R! NO TE F m an . making y books there is no end Surely , the weary observation of the sage must have an especial application to the literature of Song . — One could not number the books anatomical , physio — on . logical , philosophical the Voice A spacious library “ could easily be furnished with Methods of Singing. Works treating of the laws governing the effective interpretation of instrumental music exist . Some of them , by acknowledged and competent authorities , have thrown valuable light on a most important element of l musical art . Had I not be ieved that a similar need existed in connection with singing , this addition to vocal literature would not have been written . “ In a succeeding volume on Lyric Declamation : Reci ” tative c , Song and B allad Singing , will be dis ussed the practical application of these basic principles of Style to a G F the voc l music of the erman , rench , Italian and other national schools . E . LA W . HAS M . 2 i , rue Malev lle , P P arc Monceau , aris , 1 1 1 July , 9 . IN TRO DU C TIO N . " N P ! a Paderewski I listening to a atti , a ubelik , , the reflective hearer is struck by the absolute surenes s with which such artists arouse certain sensations in their auditors . Moreover , subsequent hearings will reveal ' the fact that this sensation is aroused always in the same the place , and in same manner . The beauty of the f voice may be temporarily a fected in the case of a singer , or an instrument of less aesthetic tone - quality be used b y the instrumentalist , but the result is always the same . -

Men's Glee Repertoire (2002-2021)

MEN'S GLEE REPERTOIRE (2002-2021) Ain-a That Good News - William Dawson All Ye Saints Be Joyful - Katherine Davis Alleluia - Ralph Manuel Ave Maria - Franz Biebl Ave Maria - Jacob Arcadet Ave Maria - Joan Szymko Ave Maris Stella - arr. Dianne Loomer Beati Mortui - Fexlix Mendelssohn Behold the Lord High Executioner (from The Mikado )- Gilbert and Sullivan Blades of Grass and Pure White Stones -Orin Hatch, Lowell Alexander, Phil Nash/ arr. Keith Christopher Blagoslovi, dushé moyá Ghospoda - Mikhail Mikhailovich Ippolitov-Ivanov Blow Ye Trumpet - Kirke Mechem Bright Morning Stars - Shawn Kirchner Briviba – Ēriks Ešenvalds Brothers Sing On - arr. Howard McKinney Brothers Sing On - Edward Grieg Caledonian Air - arr. James Mullholland Come Sing to Me of Heaven - arr. Aaron McDermid Cornerstone – Shawn Kirchner Coronation Scene (from Boris Goudonov ) - Modest Petrovich Moussorgsky Creator Alme Siderum - Richard Burchard Daemon Irrepit Callidu- György Orbain Der Herr Segne Euch (from Wedding Cantata ) - J. S. Bach Dereva ni Mungu – Jake Runestad Dies Irae - Z. Randall Stroope Dies Irae - Ryan Main Do You Hear the Wind? - Leland B. Sateren Do You Hear What I Hear? - arr. Harry Simeone Down in the Valley - George Mead Duh Tvoy blagi - Pavel Chesnokov Entrance and March of the Peers (from Iolanthe)- Gilbert and Sullivan Five Hebrew Love Songs - Eric Whitacre For Unto Us a Child Is Born (from Messiah) - George Frideric Handel Gaudete - Michael Endlehart Git on Boa'd - arr. Damon H. Dandridge Glory Manger - arr. Jon Washburn Go Down Moses - arr. Moses Hogan God Who Gave Us Life (from Testament of Freedom) - Randall Thompson Hakuna Mungu - Kenyan Folk Song- arr. William McKee Hark! I Hear the Harp Eternal - Craig Carnahan He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands - arr. -

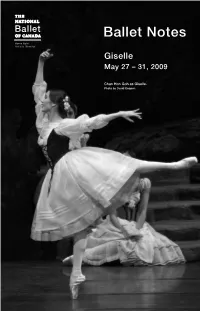

Ballet Notes Giselle

Ballet Notes Giselle May 27 – 31, 2009 Chan Hon Goh as Giselle. Photo by David Cooper. 2008/09 Orchestra Violins Clarinets • Fujiko Imajishi, • Max Christie, Principal Souvenir Book Concertmaster Emily Marlow, Lynn Kuo, Acting Principal Acting Concertmaster Gary Kidd, Bass Clarinet On Sale Now in the Lobby Dominique Laplante, Bassoons Principal Second Violin Stephen Mosher, Principal Celia Franca, C.C., Founder James Aylesworth, Jerry Robinson Featuring beautiful new images Acting Assistant Elizabeth Gowen, George Crum, Music Director Emeritus Concertmaster by Canadian photographer Contra Bassoon Karen Kain, C.C. Kevin Garland Jennie Baccante Sian Richards Artistic Director Executive Director Sheldon Grabke Horns Xiao Grabke Gary Pattison, Principal David Briskin Rex Harrington, O.C. Nancy Kershaw Vincent Barbee Music Director and Artist-in-Residence Sonia Klimasko-Leheniuk Derek Conrod Principal Conductor • Csaba Koczó • Scott Wevers Yakov Lerner Trumpets Magdalena Popa Lindsay Fischer Jayne Maddison Principal Artistic Coach Artistic Director, Richard Sandals, Principal Ron Mah YOU dance / Ballet Master Mark Dharmaratnam Aya Miyagawa Raymond Tizzard Aleksandar Antonijevic, Guillaume Côté, Wendy Rogers Chan Hon Goh, Greta Hodgkinson, Filip Tomov Trombones Nehemiah Kish, Zdenek Konvalina, Joanna Zabrowarna David Archer, Principal Heather Ogden, Sonia Rodriguez, Paul Zevenhuizen Robert Ferguson David Pell, Piotr Stanczyk, Xiao Nan Yu Violas Bass Trombone Angela Rudden, Principal Victoria Bertram, Kevin D. Bowles, Theresa Rudolph Koczó, Tuba -

Offenbach Et L'opéra-Comique

Offenbach et l’opéra-comique Lionel Pons avril 2017 Les rapports de Jacques Offenbach (1819-1880) avec le genre opéra-comique relèvent, tout au long de la vie créatrice du compositeur, d’un paradoxe amoureux. La culture lyrique d’Offenbach, son expérience en tant que violoncelliste dans l’orchestre de l’Opéra-Comique, son goût personnel pour ce genre si français, qui ne dissimule pas sa dette envers le dernier tiers du XVIIIe siècle vont nécessairement le pousser à s’intéresser au genre. Le répertoire de François Adrien Boieldieu (1775-1834), de Ferdinand Hérold (1791-1833), de Nicolò Isouard (1773-1818) lui est tout à fait familier, et quoique d’un esprit particulièrement mordant, il en apprécie le caractère sentimental et la délicatesse de touche. Et presque naturellement, il développe pourtant une conscience claire de ce que réclame impérativement la survie du genre. Offenbach sauveteur de l’opéra-comique ? L’opéra-comique, tel qu’Offenbach le découvre en ce début de XIXe siècle, est l’héritier direct des ouvrages d’André-Ernest-Modeste Grétry (1741-1813), de Pierre-Alexandre Monsigny (1729-1817) ou de Nicolas Dalayrac (1753-1809). Le genre est le fruit d’une période transitionnelle (il occupe dans le répertoire français la place chronologique du classicisme viennois outre Rhin, entre le crépuscule baroque et l’affirmation du romantisme), et reflète assez logiquement le goût de l’époque pour une forme de sentimentalité, sensible en France dans toutes les disciplines artistiques entre 1760 et 1789. Les gravures de Jean-Baptiste Greuze (1725-1805), l’architecture du Hameau de Marie-Antoinette (1783-1876), due à Richard Mique (1728-1794), l’orientation morale de L’autre Tartuffe ou la mère coupable (1792) de Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais (1732-1799), La nouvelle Héloïse (1761) de Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778) ou Paul et Virginie (1787) d’Henri Bernardin de Saint-Pierre (1737-1814) portent témoignage de cette tendance esthétique. -

L'autorité, 5 Octobre 1895, Pp

JOURNAL DES DÉBATS, 14 mai 1856, p. 2. Il y a trois jours à peine nous nous trouvions tous bien douloureusement réunis autour du cercueil d’Adolphe Adam, artistes, littérateurs, fonctionnaires, hommes du monde, amis; et il n’était pas un de nous qui n’eût à raconter quelqu’une de ces choses si simples en elles- mêmes et devenues trop à coup si étranges par l’interposition soudaine de la mort. Le vendredi 2 mai Adolphe Adam était allé dans la matinée chez ses éditeurs; il y avait traité de ses affaires, parlé de ses projets avec sa présence d’esprit et son activité ordinaires; il était plein de vie, hélas! et d’illusions. Après dîner, il partagea sa soirée entre deux théâtres, le Théâtre-Lyrique et l’Opéra, où plusieurs d’entre nous lui avaient serré la main. Rentré chez lui, il s’endormit pour ne plus se réveiller, à côté de cette page de musique humide encore qui avait reçu sa dernière pensée restée inachevée. Et nous qui chaque jour pouvions nous attendre à rendre compte d’un nouvel ouvrage du fécond compositeur, nous voilà tout à coup obligé de recueillir à la hâte quelques dates et quelques notes pour en composer sa nécrologie. Le père d’Adolphe Adam, Louis Adam, né à Miettersholtz, en Alsace, en 1759, et qui fut pendant quarante-quatre ans professeur de piano au Conservatoire de Paris, par un contraste bien triste aujourd’hui, prolongea son existence jusqu’à près de quatre-vingt-dix ans. Adolphe Adam naquit à Paris, le 24 juillet 1802. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO U SER S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.Broken or indistinct phnt, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough. substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthonzed copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion Oversize materials (e g . maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMl® UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE MICHAEL HEAD’S LIGHT OPERA, KEY MONEY A MUSICAL DRAMATURGY A Document SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS By MARILYN S. GOVICH Norman. Oklahoma 2002 UMl Number: 3070639 Copyright 2002 by Govlch, Marilyn S. All rights reserved. UMl UMl Microform 3070639 Copyright 2003 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17. United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O. -

May 19 – June 30, 2021

LOUISVILLE BALLET MAY 19 – JUNE 30, 2021 CHORSHOW Louisville Ballet Studio Company Dancer Louisville Ballet Studio Elizabeth Abbick Company Artist from “The Movement” / Sarah Bradley from “Circadian” / ChorShow 2021 ChorShow 2021 #CHORSHOW 2021 Featuring new works by Danielle Rowe, Justin Michael Hogan, Sanjay Saverimuttu, Natalie Orms, and Brandon Ragland. Cinematography & Post Production by KERTIS: Producers: Aaron Mikel & Sawyer Roque Videographers: Aaron Mikel & Alan Miller Editors: Kaylee Everly, Tobias Van Kleeck, & Wesley Bacon Lighting: Jesse Alford Costume Design: Alexandra Ludwig Stage Manager: Kim Aycock Technical Director: Brian Sherman Louisville Ballet would like to thank our generous donors for making this production possible. Louisville Ballet would also like to thank The Fund for the Arts for its generous investment in our Organization and support for our fellow arts organizations across the state. We also deeply appreciate the Kentucky Arts Council, the state arts agency, which provides operating support to Louisville Ballet with state tax dollars and federal funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, as well as significant advocacy on behalf of Louisville Ballet and our fellow arts organizations across The Commonwealth. 2 NOTES FROM THE ROBERT ARTISTIC DIRECTOR CURRAN Welcome to the final, original film of our fully digital Season of Illumination, Choreographers’ Showcase, fondly known as #ChorShow, a program created by and for our Louisville Ballet dancers. This always popular, often sold out, in-studio production might feel a little different this year, but the process and the intimacy remain. As always the final production features new works by dancers from the Company, as well as a piece by San Francisco-based guest choreographer, Danielle Rowe, this time created remotely, from a screen to our studio.