Community College Female Faculty Transitioning To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

A FUTURISTIC PORTABLE DIY LAPTOP What We Stand For

The Android APK • SEGA Gaming on your ODROID • Linux Gaming Year One Issue #9 Sep 2014 ODROIDMagazineMagazine BUILD YOUR OWN WALL-E THE LOVABLE PIXAR ROBOT COMES TO LIFE WITH AN ODROID-U3 • BASH BASICS • FREEDOMOTIC 3D PRINT AN • WEATHER FORECAST ODROID-POWERED • 10-NODE U3 CLUSTER • ODROID-SHOW GARDENING SYSTEM 3DPONICS PLUS: A FUTURISTIC PORTABLE DIY LAPTOP What we stand for. We strive to symbolize the edge technology, future, youth, humanity, and engineering. Our philosophy is based on Developers. And our efforts to keep close relationships with developers around the world. For that, you can always count on having the quality and sophistication that is the hallmark of our products. Simple, modern and distinctive. So you can have the best to accomplish everything you can dream of. We are now shipping the ODROID U3 devices to EU countries! Come and visit our online store to shop! Address: Max-Pollin-Straße 1 85104 Pförring Germany Telephone & Fax phone : +49 (0) 8403 / 920-920 email : [email protected] Our ODROID products can be found at http://bit.ly/1tXPXwe EDITORIAL With the introduction of the ODROID-W and ODROID Weath- er Board, there have been several projects posted recently on the ODROID forums involving home automation, ambient lighting, and cool robotics. This month, we feature several of those projects, including predicting whether to go fishing this weekend, building a custom laptop case, taking care of your garden remotely, and building a faithful reproduction of everyone’s favorite robot, Wall-E! Hardkernel will be demonstrat- ing the new XU3 at ARM Techcon on Oc- tober 1st - 3rd, 2014 in San Jose, Califor- nia. -

Regent Assay's View of the Month

FEBRUARY 2021 TMT M&A MONTHLY BRIEFING After entering the Dutch market last month, Spanish Regent Assay’s View of the Month Cellnex announced on 3 February that it had reached The M&A market in the European TMT sector seems to have an agreement with Altice and Starlight Holdco to gained in momentum this month. The total number of acquire Hivory, a French telecommunications tower operator which manages 10,500 sites and mainly transactions increased from 194 in January to 216 in February, serves mobile operator SFR as anchor tenant. The its highest figure since July 2020, while the announced deal agreement represents an investment of $6.2 billion by value, which had dropped to a record low of $14bn in January, Cellnex, to be accompanied by a further $1 billion for bounced back to $30bn. The P/S ratio declined slightly to 2.3x the roll-out of up to 2,500 new sites. Cellnex Telecom but remained above 2x for the fourth month in a row, while the expects its backlog of contracted sales to increase by P/EBITDA figure jumped to 11.5x, which is above its 12-month about $16 billion to about $120billion following the deal. average. Cross-border activity accounted for a large number of transactions once again, particularly in the upper-end of the Sweden-based games developer, Embracer Group, market (see below). acquired Gearbox Entertainment, on 2 February, for $1.3bn. Following the acquisition, Gearbox, which is based in Texas (USA), will become Embracer’s seventh operating group and its second in North Number of TMT Transactions in Europe Deal value deals ($b) America alongside Saber Interactive. -

The Role of Audio for Immersion in Computer Games

CAPTIVATING SOUND THE ROLE OF AUDIO FOR IMMERSION IN COMPUTER GAMES by Sander Huiberts Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD at the Utrecht School of the Arts (HKU) Utrecht, The Netherlands and the University of Portsmouth Portsmouth, United Kingdom November 2010 Captivating Sound The role of audio for immersion in computer games © 2002‐2010 S.C. Huiberts Supervisor: Jan IJzermans Director of Studies: Tony Kalus Examiners: Dick Rijken, Dan Pinchbeck 2 Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. 3 Contents Abstract__________________________________________________________________________________________ 6 Preface___________________________________________________________________________________________ 7 1. Introduction __________________________________________________________________________________ 8 1.1 Motivation and background_____________________________________________________________ 8 1.2 Definition of research area and methodology _______________________________________ 11 Approach_________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Survey methods _________________________________________________________________________ 12 2. Game audio: the IEZA model ______________________________________________________________ 14 2.1 Understanding the structure -

Stubbs the Zombie: Rebel Without 21 Starship Troopers PC Continues to Set the Standard for Both Technology and Advancements in Gameplay

Issue 07 THE WAY It’s Meant To Be Played Peter Jackson’s King Kong Age Of Empires III Serious Sam 2 Blockbusters Enjoy the season’s hottest games on the hottest gaming platform Chronicles Of Narnia: The Lion, The Witch City Of Villains F.E.A.R And The Wardrobe NNVM07.p01usVM07.p01us 1 119/9/059/9/05 33:57:57:57:57 ppmm The way it’s meant to be played 3 6 7 8 Welcome Welcome to Issue 7 of The Way It’s Meant 12 13 to be Played, the magazine that showcases the very best of the latest PC games. All the 30 titles featured in this issue are participants in NVIDIA’s The Way It’s Meant To Be Played program, a campaign designed to deliver the best interactive entertainment experience. Development teams taking part in 14 19 the program are given access to NVIDIA’s hardware, with NVIDIA’s developer technology engineers on hand to help them get the very best graphics and effects into their new games. The games are then rigorously tested by NVIDIA for compatibility, stability and reliability to ensure that customers can buy any game with the TWIMTBP logo on the box and feel confident that the game will deliver the ultimate install- and-play experience when played with an Contents NVIDIA GeForce-based graphics card. Game developers today like to use 3 NVIDIA news 14 Chronicles Of Narnia: The Lion, Shader Model 3.0 technology for stunning, The Witch And The Wardrobe complex cinematic effects – a technology TWIMTBP games 15 Peter Jackson’s King Kong fully supported by all the latest NVIDIA 4 Vietcong 2 16 F.E.A.R. -

2K, Gearbox Software Announce Next-Gen IP, Battlebornâ„¢ July 8

2K, Gearbox Software Announce Next-Gen IP, Battleborn™ July 8, 2014 12:05 PM ET New hero-shooter experience from the creators of the best-selling Borderlands franchise brings industry-leading co-operative and competitive play to next-gen consoles and PC Join the conversation on Twitter using the hashtag #Battleborn NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Jul. 8, 2014-- 2K and Gearbox Software – the creators of the award-winning and best-selling Borderlands franchise – today announced Battleborn™, an all-new full-featured triple-A hero-shooter experience for Xbox One, the all-in-one games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®4 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC is in development. The first details and full reveal of Battleborn can be read now exclusively in Game Informer magazine’s August issue cover story. Battleborn is developed by the teams behind the critically acclaimed hybrid role-playing-shooter Borderlands 2, and is an ambitious fusion of genres. The game combines highly-stylized visuals and frenetic first-person shooting, with Gearbox’s industry-leading co-operative combat, and an expansive collection of diverse heroes. Battleborn is set in the distant future of an imaginative science-fantasy universe where players experience both a narrative-driven co-operative campaign, as well as competitive multiplayer matches. “If Borderlands 2 is a shooter-looter, Battleborn is a hero-shooter,― said Randy Pitchford, president of Gearbox Software. “As a genre-fused, hobby-grade, co-operative and competitive FPS exploding with eye-popping style and an imaginative universe, Battleborn is the most ambitious video game that Gearbox has ever created.― “Battleborn represents the combined might of the development and publishing teams behind the success of Borderlands 2, which to date has sold-in more than 9-million units worldwide and has become 2K’s highest-selling game of all time,― said Christoph Hartmann, president of 2K. -

Functional Requirements for Broadband Residential Gateway Devices

TECHNICAL REPORT TR-124 Functional Requirements for Broadband Residential Gateway Devices Issue: 5 Issue Date: July 2016 © The Broadband Forum. All rights reserved. Functional Requirements for Broadband Residential Gateway Devices TR-124 Issue 5 Notice The Broadband Forum is a non-profit corporation organized to create guidelines for broadband network system development and deployment. This Technical Report has been approved by members of the Forum. This Technical Report is subject to change. This Technical Report is copyrighted by the Broadband Forum, and all rights are reserved. Portions of this Technical Report may be copyrighted by Broadband Forum members. Intellectual Property Recipients of this Technical Report are requested to submit, with their comments, notification of any relevant patent claims or other intellectual property rights of which they may be aware that might be infringed by any implementation of this Technical Report, or use of any software code normatively referenced in this Technical Report, and to provide supporting documentation. Terms of Use 1. License Broadband Forum hereby grants you the right, without charge, on a perpetual, non-exclusive and worldwide basis, to utilize the Technical Report for the purpose of developing, making, having made, using, marketing, importing, offering to sell or license, and selling or licensing, and to otherwise distribute, products complying with the Technical Report, in all cases subject to the conditions set forth in this notice and any relevant patent and other intellectual property rights of third parties (which may include members of Broadband Forum). This license grant does not include the right to sublicense, modify or create derivative works based upon the Technical Report except to the extent this Technical Report includes text implementable in computer code, in which case your right under this License to create and modify derivative works is limited to modifying and creating derivative works of such code. -

Contents ,,,;;=Y=St=E=M==: =M=S=D=O=S==(=R=Eq=U=I=Re=D=: ~' Ancient Snake Cult)

Vol. X, #5 Not sold in stores ··---··--· - - - l.JLTIMA VII PART 2 e any moons have passed - more features, the latest graphic striving to retain enough of the old to some of them twin moons - innovations and other technological satisfy those people. I am merely M since I last reviewed an nuances. And enough new characters echoing what I've heard from quite a Ull ima. I've played them all to some to hold your attention. But underneath few other Ultima vets who would extent, of course, but have not spent this glittering surface, we still face also love to run Iola through with a so much time in H.ichard Garriott 's much the same in rusty halberd.) fantasy worlds since Ultima I V My terms of game play initial impression, borne out by a and design. On with the shoe week of questing, is that no maner Your goal, for Part of a trilogy that how many technological innovations instance, involves will comprise Ultima are introduced, U1timawill always be restoring the VII through IX, basicaliy the same game -- Ultima. "I3alance" between Serpent's Isle raises This indicates character and integrity, Chaos and Order - the curtain with a yet tread<; dangerously near the both composed of cinematic sequence at pitfall of redundancy and stereotyp Forces such as Lord British's castle. ing. Only madmen and geniuses (and Tolerance, Logic The Guardian, foiled in his effort to the occasional drunk) dare such a and other traits reminiscent of the enter Britannia through the Black ri sk. virtues introduced in Ultima IV. -

Tabletop Role-Playing Games and the Experience of Imagined

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M Repository THE GREATEST UNREALITY: TABLETOP ROLE-PLAYING GAMES AND THE EXPERIENCE OF IMAGINED WORLDS A Dissertation by NICHOLAS J. MIZER Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, Tom Green Committee Members, Harris Berger Vaughn Bryant Travis Dubry Head of Department, Cynthia Werner December 2015 Major Subject: Anthropology Copyright 2015 Nicholas J. Mizer ABSTRACT Drawing on four years of participant observation, interviews, and game recordings, this dissertation explores the collaborative experience of imagined worlds in tabletop role- playing games such as Dungeons & Dragons. Research on tabletop games has at times been myopic in terms of time depth and geographic scope, and has often obscured the ethnographic realities of gaming communities. This research expands the ethnographic record on tabletop role-playing games and uses a phenomenological approach to carefully examine how gamers at five sites across the United States structure their experience of imagined worlds in the context of a productive tension between enchantment and rationalization. After discussing the history of Dungeons & Dragons in terms of enchantment and rationalization, the dissertation presents three case studies, each exploring a different facet of experience in imagined worlds. At a convention in Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, gamers commemorate the life of Dungeons & Dragons co-creator Gary Gygax, but also their own childhoods and a sense of a lost, imagined pre-modern world. -

Application: Unity 3D Web Player

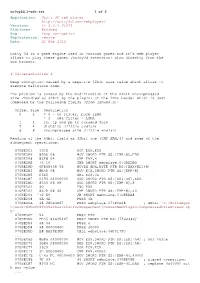

unity3d_1-adv.txt 1 of 2 Application: Unity 3D web player http://unity3d.com/webplayer/ Versions: <= 3.2.0.61061 Platforms: Windows Bug: heap corruption Exploitation: remote Date: 21 Feb 2012 Unity 3d is a game engine used in various games and it’s web player allows to play these games (unity3d extension) also directly from the web browser. # Vulnerabilities # Heap corruption caused by a negative 32bit size value which allows to execute malicious code. The problem is caused by the modification of the 64bit uncompressed size (handled as 32bit by the plugin) of the lzma header which is just composed by the following fields (from lzma86.h): Offset Size Description 0 1 = 0 - no filter, pure LZMA = 1 - x86 filter + LZMA 1 1 lc, lp and pb in encoded form 2 4 dictSize (little endian) 6 8 uncompressed size (little endian) Reading of the 64bit field as 32bit one (CMP EAX,4) and some of the subsequent operations: 070BEDA3 33C0 XOR EAX,EAX 070BEDA5 895D 08 MOV DWORD PTR SS:[EBP+8],EBX 070BEDA8 83F8 04 CMP EAX,4 070BEDAB 73 10 JNB SHORT webplaye.070BEDBD 070BEDAD 0FB65438 05 MOVZX EDX,BYTE PTR DS:[EAX+EDI+5] 070BEDB2 8B4D 08 MOV ECX,DWORD PTR SS:[EBP+8] 070BEDB5 D3E2 SHL EDX,CL 070BEDB7 0196 A4000000 ADD DWORD PTR DS:[ESI+A4],EDX 070BEDBD 8345 08 08 ADD DWORD PTR SS:[EBP+8],8 070BEDC1 40 INC EAX 070BEDC2 837D 08 40 CMP DWORD PTR SS:[EBP+8],40 070BEDC6 ^72 E0 JB SHORT webplaye.070BEDA8 070BEDC8 6A 4A PUSH 4A 070BEDCA 68 280A4B07 PUSH webplaye.074B0A28 ; ASCII "C:/BuildAgen t/work/b0bcff80449a48aa/PlatformDependent/CommonWebPlugin/CompressedFileStream.cp p" 070BEDCF 53 PUSH EBX 070BEDD0 FF35 84635407 PUSH DWORD PTR DS:[7546384] 070BEDD6 6A 04 PUSH 4 070BEDD8 68 00000400 PUSH 40000 070BEDDD E8 BA29E4FF CALL webplaye.06F0179C .. -

GOG-API Documentation Release 0.1

GOG-API Documentation Release 0.1 Gabriel Huber Jun 05, 2018 Contents 1 Contents 3 1.1 Authentication..............................................3 1.2 Account Management..........................................5 1.3 Listing.................................................. 21 1.4 Store................................................... 25 1.5 Reviews.................................................. 27 1.6 GOG Connect.............................................. 29 1.7 Galaxy APIs............................................... 30 1.8 Game ID List............................................... 45 2 Links 83 3 Contributors 85 HTTP Routing Table 87 i ii GOG-API Documentation, Release 0.1 Welcome to the unoffical documentation of the APIs used by the GOG website and Galaxy client. It’s a very young project, so don’t be surprised if something is missing. But now get ready for a wild ride into a world where GET and POST don’t mean anything and consistency is a lucky mistake. Contents 1 GOG-API Documentation, Release 0.1 2 Contents CHAPTER 1 Contents 1.1 Authentication 1.1.1 Introduction All GOG APIs support token authorization, similar to OAuth2. The web domains www.gog.com, embed.gog.com and some of the Galaxy domains support session cookies too. They both have to be obtained using the GOG login page, because a CAPTCHA may be required to complete the login process. 1.1.2 Auth-Flow 1. Use an embedded browser like WebKit, Gecko or CEF to send the user to https://auth.gog.com/auth. An add-on in your desktop browser should work as well. The exact details about the parameters of this request are described below. 2. Once the login process is completed, the user should be redirected to https://www.gog.com/on_login_success with a login “code” appended at the end. -

2012 Video Game Industry Litigation Review

Science and Technology Law Review Volume 16 Number 1 Article 13 2013 2012 Video Game Industry Litigation Review Tanner Robinson Max Metzler Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/scitech Recommended Citation Tanner Robinson & Max Metzler, 2012 Video Game Industry Litigation Review, 16 SMU SCI. & TECH. L. REV. 1 (2013) https://scholar.smu.edu/scitech/vol16/iss1/13 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Science and Technology Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. 2012 Video Game Industry Litigation Review Tanner Robinson* Max Metzler** As far as significant gaming law developments are concerned, 2011 was a tough act to follow.' Last year a new paradigm emerged-courts applied the test set forth in Hart v. Electronic Arts, Inc. to lawsuits involving celebri- ties' publicity rights in video games, 2 and the Supreme Court validated a new art form in Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association.3 While not new in 2012, an important trend certainly continued in a significant way: the video game industry continued to become more mainstream.4 As video games continue to cross demographic lines and become more ubiquitous, production companies begin to resemble those in other industries. As a result of risk-focused business decisions and industry growth, many of last year's contentious lawsuits have settled. As the scope of a business expands, the variety of its contracts tends to expand as well.