+Tuhinga 23 Final:Layout 1 12/6/12 9:29 AM Page 53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kerikeri Mission House Conservation Plan

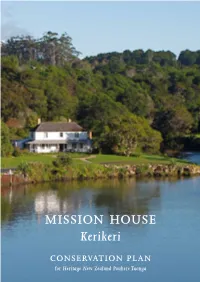

MISSION HOUSE Kerikeri CONSERVATION PLAN i for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Mission House Kerikeri CONSERVATION PLAN This Conservation Plan was formally adopted by the HNZPT Board 10 August 2017 under section 19 of the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014. Report Prepared by CHRIS COCHRAN MNZM, B Arch, FNZIA CONSERVATION ARCHITECT 20 Glenbervie Terrace, Wellington, New Zealand Phone 04-472 8847 Email ccc@clear. net. nz for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Northern Regional Office Premier Buildings 2 Durham Street East AUCKLAND 1010 FINAL 28 July 2017 Deed for the sale of land to the Church Missionary Society, 1819. Hocken Collections, University of Otago, 233a Front cover photo: Kerikeri Mission House, 2009 Back cover photo, detail of James Kemp’s tool chest, held in the house, 2009. ISBN 978–1–877563–29–4 (0nline) Contents PROLOGUES iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Commission 1 1.2 Ownership and Heritage Status 1 1.3 Acknowledgements 2 2.0 HISTORY 3 2.1 History of the Mission House 3 2.2 The Mission House 23 2.3 Chronology 33 2.4 Sources 37 3.0 DESCRIPTION 42 3.1 The Site 42 3.2 Description of the House Today 43 4.0 SIGNIFICANCE 46 4.1 Statement of Significance 46 4.2 Inventory 49 5.0 INFLUENCES ON CONSERVATION 93 5.1 Heritage New Zealand’s Objectives 93 5.2 Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 93 5.3 Resource Management Act 95 5.4 World Heritage Site 97 5.5 Building Act 98 5.6 Appropriate Standards 102 6.0 POLICIES 104 6.1 Background 104 6.2 Policies 107 6.3 Building Implications of the Policies 112 APPENDIX I 113 Icomos New Zealand Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Heritage Value APPENDIX II 121 Measured Drawings Prologue The Kerikeri Mission Station, nestled within an ancestral landscape of Ngāpuhi, is the remnant of an invitation by Hongi Hika to Samuel Marsden and Missionaries, thus strengthening the relationship between Ngāpuhi and Pākeha. -

Agenda of Kaikohe-Hokianga Community Board Meeting

KAIKOHE-HOKIANGA COMMUNITY BOARD Waima Wesleyan Mission Station 1858 by John Kinder AGENDA Kaikohe-Hokianga Community Board Meeting Wednesday, 4 August, 2021 Time: 10.30 am Location: Council Chamber Memorial Avenue Kaikohe Membership: Member Mike Edmonds - Chairperson Member Emma Davis – Deputy Chairperson Member Laurie Byers Member Kelly van Gaalen Member Alan Hessell Member Moko Tepania Member Louis Toorenburg Member John Vujcich Far North District Council Kaikohe-Hokianga Community Board Meeting Agenda 4 August 2021 The Local Government Act 2002 states the role of a Community Board is to: (a) Represent, and act as an advocate for, the interests of its community. (b) Consider and report on all matters referred to it by the territorial authority, or any matter of interest or concern to the community board. (c) Maintain an overview of services provided by the territorial authority within the community. (d) Prepare an annual submission to the territorial authority for expenditure within the community. (e) Communicate with community organisations and special interest groups within the community. (f) Undertake any other responsibilities that are delegated to it by the territorial authority Council Delegations to Community Boards - January 2013 The "civic amenities" referred to in these delegations include the following Council activities: • Amenity lighting • Cemeteries • Drainage (does not include reticulated storm water systems) • Footpaths/cycle ways and walkways. • Public toilets • Reserves • Halls • Swimming pools • Town litter • Town beautification and maintenance • Street furniture including public information signage. • Street/public Art. • Trees on Council land • Off road public car parks. • Lindvart Park – a Kaikohe-Hokianga Community Board civic amenity. Exclusions: From time to time Council may consider some activities and assets as having district wide significance and these will remain the responsibility of Council. -

The Uncrowned Lion: Rank, Status, and Identity of The

Robert Kurelić THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ External Examiner Budapest May 2005 I, the undersigned, Robert Kurelić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. I also declare that no part of the thesis has been submitted in this form to any other institution of higher education for an academic degree. Budapest, 27 May 2005 __________________________ Signature TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ____________________________________________________1 ...heind graffen von Cilli und nyemermer... _______________________________ 1 ...dieser Hunadt Janusch aus dem landt Walachey pürtig und eines geringen rittermessigen geschlechts was.. -

Kaihu Valley and the Ripiro West Coast to South Hokianga

~ 1 ~ KAIHU THE DISTRICT NORTH RIPIRO WEST COAST SOUTH HOKIANGA HISTORY AND LEGEND REFERENCE JOURNAL FOUR EARLY CHARACTERS PART ONE 1700-1900 THOSE WHO STAYED AND THOSE WHO PASSED THROUGH Much has been written by past historians about the past and current commercial aspects of the Kaipara, Kaihu Valley and the Hokianga districts based mostly about the mighty Kauri tree for its timber and gum but it would appear there has not been a lot recorded about the “Characters” who made up these districts. I hope to, through the following pages make a small contribution to the remembrance of some of those main characters and so if by chance I miss out on anybody that should have been noted then I do apologise to the reader. I AM FROM ALL THOSE WHO HAVE COME BEFORE AND THOSE STILL TO COME THEY ARE ME AND I AM THEM ~ 2 ~ CHAPTERS CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY CHARACTERS NAME YEAR PLACE PAGE Toa 1700 Waipoua 5 Eruera Patuone 1769 Northland 14 Te Waenga 1800 South Hokianga 17 Pokaia 1805 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 30 Murupaenga 1806 South Hokianga – Ripiro Coast 32 Kawiti Te Ruki 1807 Ahikiwi – Ripiro Coast 35 Hongi Hika 1807 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 40 Taoho 1807 Kaipara – Kaihu Valley 44 Te Kaha-Te Kairua 1808 Ripiro Coast 48 Joseph Clarke 1820 Ripiro Coast 49 Samuel Marsden 1820 Ripiro Coast 53 John Kent 1820 South Hokianga 56 Jack John Marmon 1820 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 58 Parore Te Awha 1821 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 64 John Martin 1827 South Hokianga 75 Moetara 1830 South Hokianga - Waipoua 115 Joel Polack -

Iom'y T/ GIPE-PUNE-000986 , I • :To:

~hi " 4$$ '~----?~-,...,.,..... .......---'" ., - -~ .-. -~ J ) ,I OhananJayarao G d " I111111 11m 1I111111111~lliti;ll!iom'Y t/ GIPE-PUNE-000986 , I • :to: ....... """"" -'-- - --~ ~r 1';\, 1( J"'"~"\.,.t'" ,,' ,\..• J' .. ' i\\.1~1 ¥ L I F E OFTBE A]IIR DOST l\IOHA]I~IED KHAN, OF KA.BUL: WITH HIS POLITICAL PROCEEDINGS TOWARDS THE ENGLISH, RUSSIAN, AND PERSIAN GOVERNMENTS, IBCLI1DIB& THE VICTORY AND DISASTERS OF THE BRITISH ARMY IN AFGHANISTAN. By MOHAN LAL, ESQ., KNIGHT OP THB PSRSIAlf ORDEB OF THE LION A.ND StTN; LATELY ATTACHED TO T MISSION' IN KABUL. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. 1'.• LONDON: LONGMAN, BRO~NJ GREEN, AND LONGMANS. PATERNOSTER-ROW. 1846. VL(?JI / I (;7 L]) ~rL( G } rtg6 London :-Prlnted by WiLL ...... OLown aud Solll, Stamford Str... t .. Hm 'kosT G~CJOUS MAJESTY QUEEN VIeT ORIA . DEDicATION TO HER MOST GRACIOUS MAJESTY QUEEN VICTORI~ 80VIIBar8S OP GRE4.T BRITA.IN 4ND OF THE INDIAN EMPIRE, 4.ND TO Hila BOYAL CONsoaT, IDS ROYAL HIGHNESS THE PRINCE ALBERT. SINCE the creation of the world it has been the custom and rule of the devoted Joyal servants of every ancient and modern Government, that either on receiving marks of distinction, or the honour of being presented to their. lawful Sovereign, they submit some present showing their homage and attac.l;1ment to the Throne. This usage of submissive 'devotion has not been limited to human beings, but it has been adopted ever by other species of God's creatures, and has met with the approbation of the greatest in the world. If we trace back as far as three thousand years, we find, from tradition as well as from historical anecdotes, one of the most striking instances in an insignificant creature of God, namely, a small ant having secured a grain of rice in its forceps; crept some distance~ and having gained an access a 2 IV DEDICATION. -

On the Day of the Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Antonmaria Lupi

Xlbe ©pen Court A MONTHLY MAGAZINE DcvotcO to tbe Science of IReltafon, tbe IRelfQion ot Science, an& tbc Bitension of tbe IReliaious I^arliament fi>ea Founded by Edward C. Hegeler VOL. XXXI (No. 12) DECEMBER, 1917 NO. 739 CONTENTS: FAGB Frontispiece. Moslem College at Bidar. On the Day of the Nativity of Our Lord Jesus Christ. Antonmaria Lupi. 705 Speculation in Science and Philosophy. John Wright Buckham 716 Ho7i' Rubber is Made (Illitstrated). A. M. Reese 720 Hebrezv Education During the Pre-Exilic Period. Fletcher H. Swift 725 Hume's Suppressed Essays. (\\^ith Editorial Introduction.) 740 Consoling Thoughts on Earthly Existence and Confidence in an Eternal Life. Hel.mutii von Moltke 756 A Moslem Edition of the Koran. Pat'l Carus 761 A Letter from our Paris Correspondent^ M. Lucien Arrcat 764 Nadivorna 766 Mohammedan Learning 767 Bouattar (With Illustration) 768 Zbc ©pen Court publisbino Company CHICAGO Per copy, 10 cents (sixpence). Yearly, $1.00 (in the U.P.U., 5s. 6d.). Entered as Second-Class Matter March 26, 1897, at the Post Office at Chicago, 111., tinder Act of March 3, 1879 Copyriglit by The Open Court Publishing Company, 19 17 : : : THE GOSPEL OF BUDDHA By DR. PAUL CARUS Pocket Edition. Illustrated. Cloth, $i.oo; flexible leather, $1.30 This edition is a photographic reproduction of the edition de luxe which was printed in Leipsic in 1913 and ready for shipment in time to be caught by the embargo Great Britain put on all articles exported from Germany. Luckily two copies of the above edition escaped, and these were used to make the photographic reproduction of this latest edition. -

Dougal Austin

Te Hei Tiki A Cultural Continuum DOUGAL AUSTIN TeHeiTiki_TXT_KB6.indd 2-3 29/04/19 8:20 PM He kupu whakataki Introduction 9 01/ Ngā whakamāramatanga Use and meaning 15 02/ Ngā momo me ngā āhua Types and shapes 27 03/ Te pūtakenga mai Physical origins 49 04/ Ngā kōrero kairangi Exalted histories 93 Contents 05/ Ngā tohu ā-iwi Tribal styles 117 06/ Ngā tai whakaawe External versus local influence 139 07/ Ka whiti ka pūmau, 1750–1900 Change and continuity, 1750–1900 153 08/ Te whānako toi taketake, ngā tau 1890–ināianei Cultural appropriation, 1890s–present 185 09/ Te hei tiki me te Māori, 1900–ināianei Māori and hei tiki, 1900–present 199 He kupu whakakapi Epilogue 258 Appendices, Notes, Glossary, Select bibliography, Image credits, Acknowledgements, Index 263 TeHeiTiki_TXT_KB6.indd 6-7 29/04/19 8:20 PM He kupu whakataki Introduction 9 TeHeiTiki_TXT_KB6.indd 8-9 29/04/19 8:20 PM āori personal adornments take a wide variety of forms, all treasured greatly, but without a doubt Mthe human-figure pendants called hei tiki are the most highly esteemed and culturally iconic. This book celebrates the long history of hei tiki and their enduring cultural potency for the Māori people of Aotearoa. Today, these prized pendants are enjoying a resurgence in popularity, part of the late twentieth- to early twenty-first- century revitalisation of Māori culture, which continues to progress from strength to strength. In many ways the story of hei tiki mirrors the changing fortunes of a people, throughout times of prosperity, struggle, adaptation and resilience. -

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania

; 97 IHE FREiNCH IN VAN DIEMEN'S LAND, AND THE FIRST SETTLEMENT AT THE DERWENT. BY JAMES B. WALKER. Prefatory Note. As the subject of the present Paper may appear to be scarcely within the scope of the objects of the Royal Society, it seems proper to state briefly the occasion of its being written and submitted to the consideration of the Fellows. Some two years ago, the Tasmanian Government—of which the Hon. James Wilson Agnew, Honorary Secretary of the Royal Society, was Premier—following the good example set by the Governments of New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland, and Now Zealand, directed search to be made iu the English State Record Office for papers relating to the settlement and early history of this Colony. The idea originated in a suggestion from Mr. James Bonwick, F.R.G.S., the well-known writer on the Tasmanian Aborigines, who had been employed for years on similar work for various Colonial Governments, and to him the task was entrusted by Dr. Agnew. Mr. Bonwick searched, not only the Record Office, but the papers of the Admiralty, the Foreign Office, the Privy Council, and the British Museuni, and discovered and co|)ied a large mass of docunu'nts rohiting to the oarly days of Tasmania. in the early jiart of this year, these coj)ics, extending over some (J4() foolscap pages, were received in Ilobart, and the ))resent Premier —the Hon. Philip Oakley Fysh—obligingly allowed me to jioruse them. I found them to be of great interest. They threw (piite a new light on the causes which led to the first occupation of this Islaiul ; gave a complete history of Bowen's first settlement at Risdon Cove and supplied materials for other hitherto unwritten — 98 FRENCH IN VAN DIEMEN's LAND. -

Catharine J. Cadbury Papers HC.Coll.1192

William W. Cadbury and Catharine J. Cadbury papers HC.Coll.1192 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit February 23, 2012 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Haverford College Quaker & Special Collections 2011 370 Lancaster Ave Haverford, PA, 19041 610-896-1161 [email protected] William W. Cadbury and Catharine J. Cadbury papers HC.Coll.1192 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 William Warder Cadbury (1877-1959)......................................................................................................... 6 Catharine J. Cadbury (1884-1970)................................................................................................................ 6 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................7 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................ 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Related Finding Aids.....................................................................................................................................9 Collection Inventory................................................................................................................................... -

The Story of the Treaty Part 1 (Pdf

THE STORY OF THE TREATY Introduction This is the story of our founding document, the Treaty agreement contained within it. At the outset it of Waitangi. It tells of the events leading up to the should be noted that, while the steps leading to the Treaty at a time when Mäori, far outnumbering Treaty are well known and have been thoroughly Päkehä, controlled New Zealand. It describes the studied, historians do differ in what they see as the The Treaty of Waitangi is New Zealand’s founding document. Over 500 Mäori chiefs and essential bargain that was struck between Mäori main developments and trends. Some historians, for representatives of the British Crown signed the Treaty in 1840. Like all treaties it is an exchange and the British Crown and what both sides hoped example, emphasise the humanitarian beliefs of the of promises; the promises that were exchanged in 1840 were the basis on which the British to obtain by agreeing to it. However, it does not tell 1830s; others draw attention to the more coercive Crown acquired New Zealand. The Treaty of Waitangi agreed the terms on which New Zealand the full story of what has happened since the signing aspects of British policy or take a middle course would become a British colony. of the Treaty in 1840: of the pain and loss suffered of arguing that while British governments were by Mäori when the Treaty came to be ignored concerned about Mäori, they were equally concerned This is one of a series of booklets on the Treaty of Waitangi which are drawn from the Treaty of by successive settler-dominated governments in about protecting the interests of Britain and British Waitangi Information Programme’s website www.treatyofwaitangi.govt.nz. -

Historians, Tasmania

QUEEN VICTORIA MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY CHS 72 THE VON STIEGLITZ COLLECTION Historians, Tasmania INTRODUCTION THE RECORDS 1.von Stieglitz Family Papers 2.Correspondence 3.Financial Records 4.Typescripts 5.Miscellaneous Records 6.Newspaper Cuttings 7.Historical Documents 8.Historical Files 9.Miscellaneous Items 10.Ephemera 11.Photographs OTHER SOURCES INTRODUCTION Karl Rawdon von Stieglitz was born on 19 August 1893 at Evandale, the son of John Charles and Lillian Brooke Vere (nee Stead) von Stieglitz. The first members of his family to come to Van Diemen’s Land were Frederick Lewis von Stieglitz and two of his brothers who arrived in 1829. Henry Lewis, another brother, and the father of John Charles and grandfather of Karl, arrived the following year. John Charles von Stieglitz, after qualifying as a surveyor in Tasmania, moved to Northern Queensland in 1868, where he worked as a surveyor with the Queensland Government, later acquiring properties near Townsville. In 1883, at Townsville he married Mary Mackenzie, who died in 1883. Later he went to England where he married Lillian Stead in London in 1886. On his return to Tasmania he purchased “Andora”, Evandale: the impressive house on the property was built for him in 1888. He was the MHA for Evandale from 1891 to 1903. Karl von Stieglitz visited England with his father during 1913-1914. After his father’s death in 1916, he took possession of “Andora”. He enlisted in the First World War in 1916, but after nearly a year in the AIF (AMC branch) was unable to proceed overseas due to rheumatic fever. -

The-Rev-Samuel-Marsden-Episode-2

The Rev Samuel Marsden. 1765-1838. Elizabeth Marsden. 1772-1835. Episode 2. You have shared the early life of my family and heard about their voyage to NSW. We all came by boat as do many New Australians today. We will now share with them how they were surprised and pleased that they were to be given land and expected to farm that land. This is something that they could never have believed would happen in England. As I have said, I talk too much ---so on with my story. Having shared in his wife’s great adventure, Samuel went out on the deck to be rewarded with the sight of the South Cape of New Holland, the first land sighted for three months. For the next few weeks he was kept busy caring for his wife and new baby. On the 19 the. March 1794 The William sailed into Port Jackson and dropped anchor at Sydney Cove. Samuel knelt down on the deck and thanked God for His care and for delivering his family to safety. This faith would be sorely tested during his four decades of service in NSW. My family disembarked on the 10th. March and baby Ann was carried ashore in a large handkerchief belonging to Commissary John Palmer and was given a warm welcome by the Governor and many of the citizens of Sydney Town. The Rev.Johnson and his wife were very 1 pleased to see them and made them welcome at their home in Bridge St. The lived there until the 4th. July and Elizabeth was nursed back to health by the kind Mrs.