Māori Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Natural Areas of Kaikohe Ecological District Reconnaissance Survey Report for the Protected Natural Areas Programme

Natural areas of Kaikohe Ecological District Reconnaissance Survey Report for the Protected Natural Areas Programme NEW ZEALAND PROTECTED NATURAL AREAS PROGRAMME Linda Conning and Nigel Miller Published by Department of Conservation Northland Conservancy P.O. Box 842 Whangarei, New Zealand © Crown copyright 2000 This report may be freely copied provided that the Department of Conservation is acknowledged as the source of the information. Cover photograph: Ngawha Geothermal Field, Lake Waiparaheka. Topographic base maps reproduced under the Land Information New Zealand Map Authority 1991/42: Crown Copyright Reserved. ISSN: 0112-9252 ISBN: 0-478-21978-4 Cataloguing-in-Publication data Conning, Linda, 1954- Natural areas of Kaikohe Ecological District : reconnaissance survey report for the Protected Natural Areas Programme / Linda Conning and Nigel Miller. Whangarei, N.Z. : Dept. of Conservation [Northland Conservancy], 2000. 1 v. ; 30 cm. (New Zealand Protected Natural Areas Programme, 0112-9252) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0478219784 1. Ecological surveys—New Zealand—Northland Region. 2. Natural areas—New Zealand—Northland Region. I. Miller, Nigel. II. Title. III. Series: New Zealand Protected Natural Areas Programme (Series). Foreword The Kaikohe Ecological District is a compact area between the Bay of Islands and Hokianga Harbour, and harbours a wealth of ecological values including • a rare stand of dense old growth podocarp/kauri • one of Northland’s largest wetlands • unique associations of volcanic geomorphology with lakes, wetlands and uncommon plants • a suite of habitats containing the threatened North Island brown kiwi • gumlands • remnant puriri forest on volcanic soils • remnant swamp forests and shrublands as well as many other areas with significant conservation values. -

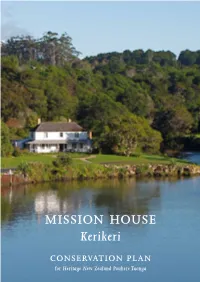

Kerikeri Mission House Conservation Plan

MISSION HOUSE Kerikeri CONSERVATION PLAN i for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Mission House Kerikeri CONSERVATION PLAN This Conservation Plan was formally adopted by the HNZPT Board 10 August 2017 under section 19 of the Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 2014. Report Prepared by CHRIS COCHRAN MNZM, B Arch, FNZIA CONSERVATION ARCHITECT 20 Glenbervie Terrace, Wellington, New Zealand Phone 04-472 8847 Email ccc@clear. net. nz for Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Northern Regional Office Premier Buildings 2 Durham Street East AUCKLAND 1010 FINAL 28 July 2017 Deed for the sale of land to the Church Missionary Society, 1819. Hocken Collections, University of Otago, 233a Front cover photo: Kerikeri Mission House, 2009 Back cover photo, detail of James Kemp’s tool chest, held in the house, 2009. ISBN 978–1–877563–29–4 (0nline) Contents PROLOGUES iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Commission 1 1.2 Ownership and Heritage Status 1 1.3 Acknowledgements 2 2.0 HISTORY 3 2.1 History of the Mission House 3 2.2 The Mission House 23 2.3 Chronology 33 2.4 Sources 37 3.0 DESCRIPTION 42 3.1 The Site 42 3.2 Description of the House Today 43 4.0 SIGNIFICANCE 46 4.1 Statement of Significance 46 4.2 Inventory 49 5.0 INFLUENCES ON CONSERVATION 93 5.1 Heritage New Zealand’s Objectives 93 5.2 Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga Act 93 5.3 Resource Management Act 95 5.4 World Heritage Site 97 5.5 Building Act 98 5.6 Appropriate Standards 102 6.0 POLICIES 104 6.1 Background 104 6.2 Policies 107 6.3 Building Implications of the Policies 112 APPENDIX I 113 Icomos New Zealand Charter for the Conservation of Places of Cultural Heritage Value APPENDIX II 121 Measured Drawings Prologue The Kerikeri Mission Station, nestled within an ancestral landscape of Ngāpuhi, is the remnant of an invitation by Hongi Hika to Samuel Marsden and Missionaries, thus strengthening the relationship between Ngāpuhi and Pākeha. -

Kaihu Valley and the Ripiro West Coast to South Hokianga

~ 1 ~ KAIHU THE DISTRICT NORTH RIPIRO WEST COAST SOUTH HOKIANGA HISTORY AND LEGEND REFERENCE JOURNAL FOUR EARLY CHARACTERS PART ONE 1700-1900 THOSE WHO STAYED AND THOSE WHO PASSED THROUGH Much has been written by past historians about the past and current commercial aspects of the Kaipara, Kaihu Valley and the Hokianga districts based mostly about the mighty Kauri tree for its timber and gum but it would appear there has not been a lot recorded about the “Characters” who made up these districts. I hope to, through the following pages make a small contribution to the remembrance of some of those main characters and so if by chance I miss out on anybody that should have been noted then I do apologise to the reader. I AM FROM ALL THOSE WHO HAVE COME BEFORE AND THOSE STILL TO COME THEY ARE ME AND I AM THEM ~ 2 ~ CHAPTERS CHAPTER 1 THE EARLY CHARACTERS NAME YEAR PLACE PAGE Toa 1700 Waipoua 5 Eruera Patuone 1769 Northland 14 Te Waenga 1800 South Hokianga 17 Pokaia 1805 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 30 Murupaenga 1806 South Hokianga – Ripiro Coast 32 Kawiti Te Ruki 1807 Ahikiwi – Ripiro Coast 35 Hongi Hika 1807 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 40 Taoho 1807 Kaipara – Kaihu Valley 44 Te Kaha-Te Kairua 1808 Ripiro Coast 48 Joseph Clarke 1820 Ripiro Coast 49 Samuel Marsden 1820 Ripiro Coast 53 John Kent 1820 South Hokianga 56 Jack John Marmon 1820 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 58 Parore Te Awha 1821 North Kaipara West coast to Hokianga 64 John Martin 1827 South Hokianga 75 Moetara 1830 South Hokianga - Waipoua 115 Joel Polack -

The Far North…

Far North Area Alcohol Accords Final Evaluation 2009 TheThe FarFar NorthNorth…… A great place to visit, live and work ISBN 978-1-877373-70-1 Prepared for ALAC by: Evaluation Solutions ALCOHOL ADVISORY COUNCIL OF NEW ZEALAND Kaunihera Whakatupato Waipiro o Aotearoa PO Box 5023 Wellington New Zealand www.alac.org.nz www.waipiro.org.nz MARCH 2010 CONTENTS PART I - INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 5 Far North: research brief ............................................................................................................................ 5 Purpose ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Objective .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Process ...................................................................................................................................................... 5 Data limitations ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Interview process ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Focus groups ............................................................................................................................................ -

The Story of the Treaty Part 1 (Pdf

THE STORY OF THE TREATY Introduction This is the story of our founding document, the Treaty agreement contained within it. At the outset it of Waitangi. It tells of the events leading up to the should be noted that, while the steps leading to the Treaty at a time when Mäori, far outnumbering Treaty are well known and have been thoroughly Päkehä, controlled New Zealand. It describes the studied, historians do differ in what they see as the The Treaty of Waitangi is New Zealand’s founding document. Over 500 Mäori chiefs and essential bargain that was struck between Mäori main developments and trends. Some historians, for representatives of the British Crown signed the Treaty in 1840. Like all treaties it is an exchange and the British Crown and what both sides hoped example, emphasise the humanitarian beliefs of the of promises; the promises that were exchanged in 1840 were the basis on which the British to obtain by agreeing to it. However, it does not tell 1830s; others draw attention to the more coercive Crown acquired New Zealand. The Treaty of Waitangi agreed the terms on which New Zealand the full story of what has happened since the signing aspects of British policy or take a middle course would become a British colony. of the Treaty in 1840: of the pain and loss suffered of arguing that while British governments were by Mäori when the Treaty came to be ignored concerned about Mäori, they were equally concerned This is one of a series of booklets on the Treaty of Waitangi which are drawn from the Treaty of by successive settler-dominated governments in about protecting the interests of Britain and British Waitangi Information Programme’s website www.treatyofwaitangi.govt.nz. -

Using Te Reo Māori and Ta Re Moriori in Taxonomy

VealeNew Zealand et al.: Te Journal reo Ma- oriof Ecologyin taxonomy (2019) 43(3): 3388 © 2019 New Zealand Ecological Society. 1 REVIEW Using te reo Māori and ta re Moriori in taxonomy Andrew J. Veale1,2* , Peter de Lange1 , Thomas R. Buckley2,3 , Mana Cracknell4, Holden Hohaia2, Katharina Parry5 , Kamera Raharaha-Nehemia6, Kiri Reihana2 , Dave Seldon2,3 , Katarina Tawiri2 and Leilani Walker7 1Unitec Institute of Technology, 139 Carrington Road, Mt Albert, Auckland 1025, New Zealand 2Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research, 231 Morrin Road, St Johns, Auckland 1072, New Zealand 3School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, 3A Symonds St, Auckland CBD, Auckland 1010, New Zealand 4Rongomaiwhenua-Moriori, Kaiangaroa, Chatham Island, New Zealand 5Massey University, Private Bag 11222 Palmerston North, 4442, New Zealand 6Ngāti Kuri, Otaipango, Ngataki, Te Aupouri, Northland, New Zealand 7Auckland University of Technology, 55 Wellesley St E, Auckland CBS, Auckland 1010, New Zealand *Author for correspondence (Email: [email protected]) Published online: 28 November 2019 Auheke: Ko ngā ingoa Linnaean ka noho hei pou mō te pārongo e pā ana ki ngā momo koiora. He mea nui rawa kia mārama, kia ahurei hoki ngā ingoa pūnaha whakarōpū. Me pēnei kia taea ai te whakawhitiwhiti kōrero ā-pūtaiao nei. Nā tēnā kua āta whakatakotohia ētahi ture, tohu ārahi hoki hei whakahaere i ngā whakamārama pūnaha whakarōpū. Kua whakamanahia ēnei kia noho hei tikanga mō te ao pūnaha whakarōpū. Heoi, arā noa atu ngā hua o te tukanga waihanga ingoa Linnaean mō ngā momo koiora i tua atu i te tautohu noa i ngā momo koiora. Ko tētahi o aua hua ko te whakarau: (1) i te mātauranga o ngā iwi takatake, (2) i te kōrero rānei mai i te iwi o te rohe, (3) i ngā kōrero pūrākau rānei mō te wāhi whenua. -

The Bible's Early Journey in NZ

The Bible’s Early Journey in New Zealand THE ARRIVAL It was so difficult in fact, that six years later Johnson was joined by an assistant. The Reverend Samuel Marsden, Towards the end of the 18th century, with the loss of later to be remembered by history as the Apostle to America’s 13 colonies in the American Revolution, Britain New Zealand, was studying at Cambridge University looked towards Asia, Africa and the Pacific to expand when he was convinced through the influence of William its empire. With Britain’s overburdened penal system, Wilberforce to become assistant chaplain to the penal expanding the empire into the newly discovered eastern colony at Port Jackson (by this time the original penal coast of Australia through the establishment of a penal colony settlement at Botany Bay had been moved). colony seemed like a decent solution. So, in 1787, six Marsden jumped at the chance to put his faith into transport ships with 775 convicts set sail for Botany Bay, practice and boarded a ship bound for Australia. He later to be renamed Sydney. arrived in Port Jackson with his wife in 1794. Thanks to the last minute intervention of philanthropist Marsden established his house at Parramatta just John Thornton and Member of Parliament William outside the main settlement at Port Jackson. There Wilberforce, a chaplain was included on one of the he oversaw his 100 acre farm as well as consenting ships. The Reverend Richard Johnson was given the to serve as a magistrate and as superintendent of unenviable task of being God’s representative in this government affairs. -

2021 Whangarei Visitor Guide

2021 VISITOR GUIDE CENTRAL WHANGĀREI TOWN BASIN TUTUKĀKĀ COAST WHANGĀREI HEADS BREAM BAY WhangareiNZ.com Whangārei Visitor Guide Cape Reinga CONTENTS EXPLOREEXPLORE 3 District Highlights 4 Culture WHANGĀREI DISTRICT 6 Cultural Attractions NINETY MILE 7 Kids Stuff BEACH 1f Take the scenic route 8 Walks Follow the Twin Coast Discovery 13 Markets signs and discover the best of 14 Beaches both the East and West Coasts. 16 Art 18 Town Basin Sculpture Trail New Zealand 20 Waterfalls Kaitaia 22 Gardens Bay of 10 Islands 23 Cycling Kerikeri 24 Events 1 36 Street Prints Manaia Art Trail H OK H IA AR NG CENTRAL BO A Climate UR Kaikohe Poor Knights 12 Islands WHANGĀREI Whangārei district is part of 1 Northland, New Zealand’s warmest CENTRAL 26 Central Whangārei Map WHANGĀREI Waipoua WHANGĀREI and only subtropical region, with 12 30 Whangārei City Centre Map Kauri TUTUKĀKĀ an average of 2000 sunshine hours Forest COAST 31 See & Do every year. The hottest months are 28 Listings January and February and winters are mild WHANGĀREI WHANGĀREI 34 Eat & Drink – there’s no snow here! 14 HEADS Average temperatures Dargaville BREAM BAY BREAM Hen & Chicken Spring: (Sep-Nov) 17°C high, 10°C low BAY Islands 12 Waipū 40 Bream Bay Map Summer: (Dec-Feb) 24°C high, 14°C low 1 42 See & Do Autumn: (Mar-May) 21°C high, 11°C low 12 Winter: (Jun-Aug) 16°C high, 07°C low 42 Listings 1 Travel distances to Whangārei WHANGĀREI HEADS • 160km north of Auckland – 2 hours drive or 30 minute flight 46 Whangārei Heads Map • 68km south of the Bay of Islands – 1 hour drive 47 See & Do UR K RBO Auckland • 265km south of Cape Reinga – 4 hours drive AIPARA HA 49 Listings TUTUKĀKĀ COAST This official visitor guide to the Whangārei district is owned by Whangarei 50 Tutukākā Coast Map District Council and produced in partnership with Big Fish Creative. -

Colonisation and the Involution of the Maori Economy Hazel Petrie

Colonisation and the Involution of the Maori Economy Hazel Petrie University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand [email protected] A paper for Session 24 XIII World Congress of Economic History Buenos Aires July 2002 In 2001, international research by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, found Maori to be the most entrepreneurial people in the world, noting also that Maori ‘played an important role in the history and evolution of New Zealand entrepreneurship’.1 These findings beg a consideration of why the Maori economy, which was expanding vigorously in terms of value and in terms of international markets immediately prior to New Zealand’s annexation by Britain in 1840, involuted soon after colonisation. Before offering examples of Maori commercial practice in the period between initial European contact and colonisation, this paper will summarise some essential features of Maori society that underlay those practices. It will then consider how three broad aspects of the subsequent colonising process impacted on these practices during its first twenty five years. These aspects are: Christian beliefs and values, the ideologies of the newly emerging ‘science’ of Political Economy; and the racial attitudes and political demands of an increasingly powerful settler government. It is acknowledged that the nature of Maori commerce varied according to regional resources, the timing and degree of exposure to foreigners, local politics, individual personalities, and many other factors. There was no one Maori practice or experience, but the examples offered, which arose in a study of Maori flourmill and trading ship ownership, are intended to show how these facets of colonisation interwove to encourage a narrowing and contraction of Maori commercial endeavours. -

BISHOP GEORGE A. SELWYN Papers, 1831-1952 Reels M590, M1093-1100

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT BISHOP GEORGE A. SELWYN Papers, 1831-1952 Reels M590, M1093-1100 Selwyn College Grange Road Cambridge CB3 9DQ National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1965, 1979 CONTENTS Page 3 Biographical notes Reel M590 4 Journals and other papers of Bishop Selwyn, 1843-57 5 Addresses presented to Bishop Selwyn, 1868-71 5 Letters of Sarah Selwyn, 1842-62 7 Miscellaneous papers, 1831-1906 Reels M1093-1100 8 Correspondence and other papers, 1831-78 26 Pictures and printed items 26 Sermons of Bishop Selwyn 27 Letters and papers of Sarah Selwyn, 1843-1907 28 Correspondence of other clergy and other papers, 1841-97 29 Letterbook, 1840-60 35 Journals and other papers of Bishop Selwyn, 1845-92 36 Letters patent and other papers BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES George Augustus Selwyn (1809-1878) was born in London, the son of William Selwyn, K.C. He was educated at Eton and St John’s College, Cambridge, graduating as a B.A. in 1831 and a M.A. in 1834. He was ordained as an Anglican priest in 1834 and served in the parish of Windsor. He married Sarah Richardson in 1838. He was consecrated the first Bishop of New Zealand on 17 October 1841 and left for New Zealand in December 1841. He was first based at Waimate, near the Bay of Islands, and immediately began the arduous journeys that were a feature of his bishopric. He moved to Auckland in 1844. In 1847-51 he made annual cruises to the islands of Melanesia. Selwyn visited England in 1854-55 and enlisted the services of the Reverend John Patteson, the future Bishop of Melanesia, and secured a missionary schooner, Southern Cross. -

WHANGAREI REGIONAL - KERIKERI Customers Can Check If an Address Is Considered Rural Or Residential by Using the ‘Address Checker’ Tool on Our Website

LOCAL SERVICES YOUR V..A NI. P N FORYOUR INFORMATION LOCAL ANDREGIONAL - SAME DAY SERVICES Customer Services Website V.A.N.Automated booking International Help Desk Local Branch 09 430 3284 Local Fax 09 430 3290 Kaitaia AUCKLAND Kerikeri Paihia Kaikohe Kawakawa Hikurangi WHANGAREI Marsden Point Branch Locations Branch Locations Waipu Dargaville Maungaturoto Local Tickets LT4 – WRE (Whangarei/Hikurangi/Waipu/Dargaville) Local Tickets Local Tickets LT3 – Mid/Far North 1 ticket per 25kg or 0.1m3 (Kaikohe/Kaitaia/Kerikeri/Paihia/Kawakawa) Outer Area Tickets 3 Kaiwaka 1 ticket per 25kg or 0.1m 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m3 Outer Area Tickets Shorthaul Tickets Wellsford 3 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025 m 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m3 Warkworth Shorthaul Tickets Longhaul Tickets Waiwera 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m3 3 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025m Longhaul Tickets Inter-Island Tickets 3 1 ticket Branch per 5kg Locations or 0.025m 3 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025m Helensville Inter-Island Tickets E-Packs Kumeu 3 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025m (Nationwide-no boundaries) AUCKLAND Local Tickets E-Packs Beachlands 1 ticket per 25kg or 0.1m3 (Nationwide ) Interdistrict Tickets Residential Delivery 1 ticket per 25kg or 0.1m3 Clevedon 1 ticket per item Drury Outer Area Tickets Rural Delivery 3 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m h Thames 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.075m3 Tuakau Shorthaul Tickets 1 ticket per 15kg or 0.025m3 Longhaul Tickets 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025m3 Huntly Inter-Island TicketsNAPIER 1 ticket per 5kg or 0.025m3 E-Packs (Nationwide-no boundaries) HAMILTON Please Note: Above zone areas are approximate only, For queries regarding the exact zone of a specific location, please contact your local branch. -

Ngā Utu Fees and Charges 2021/22

NGĀ UTU FEES AND CHARGES 2021/22 Adopted 13 May 2021 Contents Contents . 2 Animals . 1 Building consents . .. 3 Bylaw enforcement . 6 Cemeteries . 7 Certificates and licenses . 8 Infringements . 11 Leases and licenses of reserves / change of reserve status . 13 Legal services . 15 Libraries . 16 Marine . 17 Official information . 18 Property information . 19 Resource consents . 20 Rubbish disposal services at transfer stations . 24 Stormwater . 25 Transport . 26 Venues for hire . 27 Wastewater . 28 Water supply . 29 Far North District Council | Ngā Utu 2021/22 | Fees and Charges Schedule 2021/22 1 Animals Dog registration Full fee and late registration penalty Registration fee for desexed dogs 1 July 2021 – 31 August 2021 1 Sept 2021 – 30 June 2022 Pet dog $54.00 $81.00 Menacing / dangerous dog $86.00 $127.00 Working / pig dog $42.00 $62.00 Disability assist dog (approved organisation certified) No charge No charge Multiple dog discount (Register five dogs, get the sixth dog free) $0.00 n/a Discount for Gold Card or Community Card holders 10% n/a Full fee, penalty and debt recovery costs are incurred between 1 September 2021 and 30 June 2022 Full fee and late registration penalty Registration fee for non-desexed dogs 1 July 2021 – 31 August 2021 1 Sept 2021 – 30 June 2022 Pet dog $64 .00 $91.00 Menacing / dangerous dog $96 .00 $137.00 Working / pig dog $52 .00 $74.00 Disability assist dog (approved organisation certified) No charge No charge Multiple dog discount (Register five dogs, get the sixth dog free) $0 .00 n/a Discount for Gold Card or Community Card holders 10% n/a Full fee, penalty and debt recovery costs are incurred between 1 September 2021 and 30 June 2022 Other fees Re-homing dog registration fee (applies to dogs re-homed by the SPCA or via Council pounds).