1. Letter to C. F. Andrews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gandhi and Mani Bhavan

73 Gandhi and Mani Bhavan Sandhya Mehta Volume 1 : Issue 07, November 2020 1 : Issue 07, November Volume Independent Researcher, Social Media Coordinator of Mani Bhavan, Mumbai, [email protected] Sambhāṣaṇ 74 Abstract: This narrative attempts to give a brief description of Gandhiji’s association with Mani Bhavan from 1917 to 1934. Mani Bhavan was the nerve centre in the city of Bombay (now Mumbai) for Gandhiji’s activities and movements. It was from here that Gandhiji launched the first nationwide satyagraha of Rowlett Act, started Khilafat and Non-operation movements. Today it stands as a memorial to Gandhiji’s life and teachings. _______ The most distinguished address in a quiet locality of Gamdevi in Mumbai is the historic building, Mani Bhavan - the house where Gandhiji stayed whenever he was in Mumbai from 1917 to 1934. Mani Bhavan belonged to Gandhiji’s friend Revashankar Jhaveri who was a jeweller by profession and elder brother of Dr Pranjivandas Mehta - Gandhiji’s friend from his student days in England. Gandhiji and Revashankarbhai shared the ideology of non-violence, truth and satyagraha and this was the bond of their empathetic friendship. Gandhiji respected Revashankarbhai as his elder brother as a result the latter was ever too happy to Volume 1 : Issue 07, November 2020 1 : Issue 07, November Volume host him at his house. I will be mentioning Mumbai as Bombay in my text as the city was then known. Sambhāṣaṇ Sambhāṣaṇ Volume 1 : Issue 07, November 2020 75 Mani Bhavan was converted into a Gandhi museum in 1955. Dr Rajendra Prasad, then The President of India did the honours of inaugurating the museum. -

“In the Creator's Image: a Metabiographical Study of Two

IOSR Journal Of Humanities And Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) Volume 18, Issue 4 (Nov. - Dec. 2013), PP 44-47 e-ISSN: 2279-0837, p-ISSN: 2279-0845. www.iosrjournals.org “In the Creator’s Image: A Metabiographical Study of Two Visual Biographies of Gandhi”. Preeti Kumar Abstract: A metabiographical analysis is concerned with the relational nature of biographical works and stresses how the temporal, geographical, intellectual and ideological location of the biographer constructs the biographical subject differently. The changing pictures of Gandhi in his manifold biographies raise questions as to how the subject’s identity is mediated to the readers and audience. Published in 2011, the Manga biography of Gandhi by Kazuki Ebine had as one of its primary sources the film Gandhi (1982) directed by Richard Attenborough. However, in spite of closely following the cinematic text, the Gandhi in Ebine’s graphic narrative is constructed differently from the protagonist of the source text. This paper analyses the narrative devices, the cinematic and comic vocabulary, the thematic concerns and the dominant discourses underlying the two visual biographies as exemplifying the cultural and ideological profile of the biographer. Key terms: Visual Biography, metabiography, Manga, Gandhi, ideology Biography, whether in books, theatre, television and film documentaries or the new media has become the dominant narrative mode of our time. The word „biography‟ literally means „life-writing‟ from the Medieval Greek: „bios‟ meaning „life‟ and „graphia‟ or „writing‟. The earliest definition of the term was offered by Dryden in his introduction to the Lives of Plutarch, in which he referred to “biography” as the “history of particular men‟s lives”. -

Ldc Final Merit

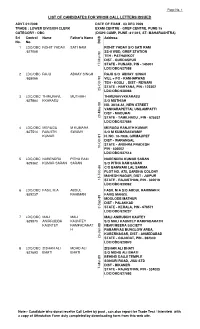

Page No. 1 LIST OF CANDIDATES FOR WHOM CALL LETTERS ISSUED ADVT-01/2009 DATE OF EXAM - 03 DEC 2009 TRADE : LOWER DIVISION CLERK EXAM CENTRE - GREF CENTRE, PUNE-15 CATEGORY - OBC (DIGHI CAMP, PUNE -411015, ST- MAHARASHTRA) Srl Control Name Father's Name Address No. No. DOB 1 LDC/OBC ROHIT YADAV SATI RAM ROHIT YADAV S/O SATI RAM /627088 SS-II WSD, GREF STATION TEH - PATHANKOT DIST - GURDASPUR STATE - PUNJAB, PIN - 145001 17-Mar-90 LDC/OBC/627088 2 LDC/OBC RAJU ABHAY SINGH RAJU S/O ABHAY SINGH /628066 VILL + PO - KANHARWAS TEH - KOSLI , DIST - REWARI STATE - HARYANA, PIN - 123302 25-Oct-90 LDC/OBC/628066 3 LDC/OBC THIRUNAVL MUTHIAH THIRUNAVVKKARASU /627884 KKARASU S/O MUTHIAH NO. 38/34 A1, NEW STREET VANNARAPETTAI, USILAMPATTI DIST - MADURAI 20-May-88 STATE - TAMILNADU , PIN - 625532 LDC/OBC/627884 4 LDC/OBC MERUGU M KUMARA MERUGU RANJITH KUMAR /627514 RANJITH SWAMY S/O M KUMARASWAMY KUMAR H. NO. 10-7936, GIRMAJIPET DIST - WARANGAL STATE - ANDHRA PRADESH 10-Oct-81 PIN - 506002 LDC/OBC/627514 5 LDC/OBC NARENDRA PITHA RAM NARENDRA KUMAR SARAN /629362 KUMAR SARAN SARAN S/O PITHA RAM SARAN C/O BANWARI LAL SARMA PLOT NO. A75, SARDHA COLONY MAHESH NAGAR, DIST - JAIPUR 15-Feb-86 STATE - RAJASTHAN, PIN - 302019 LDC/OBC/629362 6 LDC/OBC FASIL M.A ABDUL FASIL M A S/O ABDUL RAHIMAN K /629237 RAHIMAN FARIS MANZIL MOOLODE MATHUR DIST - PALAKKAD 2-Sep-89 STATE - KERALA, PIN - 678571 LDC/OBC/629237 7 LDC/OBC MALI MALI MALI ANIRUDDH KAUTEY /629870 ANIRRUDDH KAUNTEY S/O MALI KAUNTEY RAMPADARATH KAUNTEY RAMPADARAT NEAR MEERA SOCIETY H RABARIVAS BUNGLOW AREA, KUBERNAGAR, DIST - AHMEDABAD 23-Jan-88 STATE - GUJARAT, PIN - 382340 LDC/OBC/629870 8 LDC/OBC ZISHAN ALI MOHD ALI ZISHAN ALI BHATI /627693 BHATI BHATI S/O MOHD ALI BHATI BEHIND DAUJI TEMPLE SONGRI ROAD, JISU STD DIST - BIKANER 7-Mar-89 STATE - RAJASTHAN, PIN - 334005 LDC/OBC/627693 Note:- Candidate who donot receive Call Letter by post , can also report for Trade Test / Interview with a copy of Attestation Form duly completed by downloading form from this web site. -

Friends of Gandhi

FRIENDS OF GANDHI Correspondence of Mahatma Gandhi with Esther Færing (Menon), Anne Marie Petersen and Ellen Hørup Edited by E.S. Reddy and Holger Terp Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin The Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen Copyright 2006 by Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin, and The Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen. Copyright for all Mahatma Gandhi texts: Navajivan Trust, Ahmedabad, India (with gratitude to Mr. Jitendra Desai). All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transacted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum: http://home.snafu.de/mkgandhi The Danish Peace Academy: http://www.fredsakademiet.dk Friends of Gandhi : Correspondence of Mahatma Gandhi with Esther Færing (Menon), Anne Marie Petersen and Ellen Hørup / Editors: E.S.Reddy and Holger Terp. Publishers: Gandhi-Informations-Zentrum, Berlin, and the Danish Peace Academy, Copenhagen. 1st edition, 1st printing, copyright 2006 Printed in India. - ISBN 87-91085-02-0 - ISSN 1600-9649 Fred I Danmark. Det Danske Fredsakademis Skriftserie Nr. 3 EAN number / strejkode 9788791085024 2 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ESTHER FAERING (MENON)1 Biographical note Correspondence with Gandhi2 Gandhi to Miss Faering, January 11, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, January 15, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, March 20, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, March 31,1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, April 15, 1917 Gandhi to Miss Faering, -

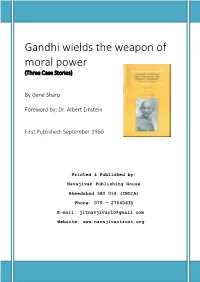

Gandhi Wields the Weapon of Moral Power (Three Case Stories)

Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power (Three Case Stories) By Gene Sharp Foreword by: Dr. Albert Einstein First Published: September 1960 Printed & Published by: Navajivan Publishing House Ahmedabad 380 014 (INDIA) Phone: 079 – 27540635 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.navajivantrust.org Gandhi wields the weapon of moral power FOREWORD By Dr. Albert Einstein This book reports facts and nothing but facts — facts which have all been published before. And yet it is a truly- important work destined to have a great educational effect. It is a history of India's peaceful- struggle for liberation under Gandhi's guidance. All that happened there came about in our time — under our very eyes. What makes the book into a most effective work of art is simply the choice and arrangement of the facts reported. It is the skill pf the born historian, in whose hands the various threads are held together and woven into a pattern from which a complete picture emerges. How is it that a young man is able to create such a mature work? The author gives us the explanation in an introduction: He considers it his bounden duty to serve a cause with all his ower and without flinching from any sacrifice, a cause v aich was clearly embodied in Gandhi's unique personality: to overcome, by means of the awakening of moral forces, the danger of self-destruction by which humanity is threatened through breath-taking technical developments. The threatening downfall is characterized by such terms as "depersonalization" regimentation “total war"; salvation by the words “personal responsibility together with non-violence and service to mankind in the spirit of Gandhi I believe the author to be perfectly right in his claim that each individual must come to a clear decision for himself in this important matter: There is no “middle ground ". -

Maulana Azad's Vision of Modern India

International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Research ISSN: 2455-2070 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.socialsciencejournal.in Volume 4; Issue 2; March 2018; Page No. 107-113 Maulana Azad‘s vision of modern India Dr. Meraj Ahmad Meraj Assistant Professor, Department of Arabic, Aliah University, Kolkata, West Bengal, India Abstract Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, a multi-dimensional personality, bloomed into a valiant freedom fighter; an apostle of Hindu-Muslim unity is one of the pioneer nation builders of modern India. He is remembered in the history of India not only for the role he played in the freedom struggle of the country, but also as the first Education Minister of independent India, he made exemplary contributions in nation-building leaving his indelible imprints in the field of education. He believed that materialization of India as a developed nation is possible only through union, solidarity and communal harmony. Maulana Azad is undoubtedly one of the architects of modern secular India who occupies a special place in the Indian History. Being a creative thinker acquainted with both traditional and modern education, Maulana Azad laid an undying impact on the educational aspects of modern India. This paper is an attempt to explore the vision and thought of Azad which were inevitable in laying down the foundation of modern India. This paper also highlights his policies and principles as existing in his writings and speeches to explore a devised to make India a centre of all intellectual and scientific developments in the world. Keywords: Moulana Azad, modern India, secularism, nationalism, Hindu-Muslim unity Introduction its cultural life is and will remain one politically. -

RRCGKP GDCE-GROUP-4 MASTER.Xlsx

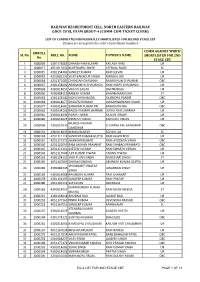

RAILWAY RECRUITMENT CELL, NORTH EASTERN RAILWAY GDCE-2018, EXAM GROUP-4 (COMM-CUM-TICKET CLERK) LIST OF CANDIDATES PROVISIONALLY SHORTLISTED FOR SECOND STAGE CBT (Names are arranged in the order of Enrollment Number) COMM AGAINST WHICH ENROLL SL No. ROLL NO. NAME FATHER'S NAME SHORTLISTED FOR 2ND No. STAGE CBT 1 1000009 4301174085 GHANSHYAM KUMAR KAILASH RAM UR 2 1000017 4051017030 KSHETRAPAL SINGH VEERVAL SINGH SC 3 1000025 4301154306 SANJEET KUMAR RAM JEEVAN UR 4 1000033 4231081236 VIJAY BAHADUR SINGH MANGAL DAS UR 5 1000034 4231171083 CHANDAN CHAUHAN RAMKISHUN CHAUHAN OBC 6 1000037 4301154002 ABHIMANYU CHAURASIA RAM ASRAY CHAURASIA UR 7 1000058 4301014093 VIDHYA SAGAR OM PRAKASH UR 8 1000060 4301084155 RAKESH KUMAR GHARBHARAN SAH ST 9 1000063 4301174140 NIDHI SHRI NANDA RAJENDRA PANDIT OBC 10 1000068 4301014077 SHAILESH KUMAR AWADHNARAYAN SINGH UR 11 1000077 4301014080 SHRAVAN KUMAR RAI BASHISHTH RAI OBC 12 1000082 4301034168 RAJESH KUMAR SHARMA JOKHU RAM SHARMA UR 13 1000085 4301014046 PARAS TIWARI RAJESH TIWARI UR 14 1000089 4301014025 INDRESH YADAV KAPILDEV YADAV UR MUKESH KUMAR 15 1000096 4301014040 CHHATRA PAL GANGWAR OBC GANGWAR 16 1000132 4301014039 MANOJ KUMAR SOHAN LAL SC 17 1000134 4231111114 SANDEEP KUMAR GUPTA RAM KHADEROO UR 18 1000135 4231171371 SHANKAR KUMAR RAM AYODHYA SINGH OBC 19 1000140 4231121095 RAM LAKHAN PRAJAPATI RAM SHABAD PRAJAPATI OBC 20 1000146 4231171361 SATEESH VERMA RAM SWARTH VERMA UR 21 1000149 4051117008 AJIT KUMAR TIWARI ANAND TIWARI UR 22 1000152 4301124133 SHIV PUJAN SINGH RAMDHARI SINGH ST 23 1000165 -

To Bid Farewell to Hon'ble Ms. Justice Sunita Gupta on Her

09.12.2016 SUPPLEMENTARY LIST SUPPLEMENTARY LIST FOR TODAY IN CONTINUATION OF THE ADVANCE LIST ALREADY CIRCULATED. THE WEBSITE OF DELHI HIGH COURT IS www.delhihighcourt.nic.in INDEX PRONOUNCEMNT OF JUDGMENTS ------------> 01 TO 02 REGULAR MATTERS -----------------------> 01 TO 77 FINAL MATTERS (ORIGINAL SIDE) ---------> 01 TO 19 ADVANCE LIST --------------------------> 01 TO 97 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 98 TO 128 APPELLATE SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY LIST)----> 129 TO 148 ORIGINAL SIDE (SUPPLEMENTARY I)--------> 149 TO 155 SECOND SUPPLEMENTARY -------------------> 156 TO 162 COMPANY -------------------------------> 163 TO PRE-LOK ADALAT -------------------------> 01 TO 02 MEDIATION CAUSE LIST ------------------> 01 TO 04 THIRD SUPPLEMENTARY -------------------> - TO TO BID FAREWELL TO HON'BLE MS. JUSTICE SUNITA GUPTA ON HER LORDSHIP'S RETIREMENT, THERE WILL BE A FAREWELL REFERENCE BY THE FULL COURT ON FRIDAY, THE 09th DECEMBER, 2016 AT 3.00 P.M. IN COURT ROOM NO. 1. NOTES 1. Special Division Bench comprising Hon'ble the Chief Justice and Hon'ble Ms. Justice Sunita Gupta will assemble at 12.00 Noon. 2. Special DB comprising Hon'ble the Chief Justice and Hon'ble Mr. Justice Jayant Nath will not assemble today. Dates will be given by the Court Master. 3. Special DB comprising Hon'ble the Chief Justice and Hon'ble Mr. Justice V. Kameswar Rao will not assemble today. Dates will be given by the Court Master. 4. Urgent mentioning may be made before Hon'ble DB-III at 10.30 A.M. 5. SH. Kovai Venugopal,Joint Registrar(Judicial) will also hear the cases listed before Ms. Anju Chhabra Khurana, Registrar(Applt.)after completion of the cases listed on his board, in Court/Room No.3,Second Floor,A Block. -

Constituent Assembly Debates

Thursday, 17th November, 1949 14-11-1949 Volume XI to 26-11-1949 CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY DEBATES OFFICIAL REPORT REPRINTED BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT, NEW DELHI SIXTH REPRINT 2014 Printed at JAINCO ART INDIA, New Delhi. THE CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA President: THE HONOURABLE DR. RAJENDRA PRASAD. Vice-President: DR. H.C. MOOKHERJEE. Constitutional Adviser: SIR B.N. RAU, C.I.E. Secretary: SHRI H.V.R. IENGAR, C.I.E., I.C.S. Joint Secretary: MR. S.N. MUKHERJEE. Deputy Secretary: SHRI JUGAL KISHORE KHANNA. Marshal: SUBEDAR MAJOR HARBANS LAL JAIDKA. CONTENTS Volume XI—14th to 26th November 1949 PAGES PAGES Monday, 14th November 1949— Monday, 21st November 1949— Draft Constitution—(Contd.) .............. 459—502 Draft Constitution—(Contd.) ............. 721—772 (Amendment of articles) Tuesday, 22nd November 1949— Tuesday, 15th November 1949— Draft Constitution—(Contd.) ............. 773—820 Draft Constitution—(Contd.) .............. 503—556 Wednesday, 23rd November 1949— [Amendments of Articles—(Contd.)] Draft Constitution—(Contd.) ............. 821—870 Thursday, 24th November 1949— Wednesday, 16th November 1949— Taking the Pledge and Signing Draft Constitution—(Contd.) .............. 557—606 the Register ..................................... 871 [Amendment of Articles—(Contd.)] Draft Constitution—(Contd.) ............. 871—922 Thursday, 17th November 1949— Friday, 25th November 1949— Draft Constitution—(Contd.) .............. 607—638 Government of India Act [Third Reading] (Amendment) Bill ........................... 923—938 Friday, 18th November 1949— Draft Constitution—(Contd.) ............. 938—981 Draft Constitution—(Contd.) .............. 639—688 Saturday, 26th November 1949— Saturday, 19th November 1949— Announcement re States .................... 983 Draft Constitution—(Contd.) .............. 689—720 Draft Constitution—(Contd.) ............. 983—996 DRAFT CONSTITUTION 607 CONSTITUENT ASSEMBLY OF INDIA Thursday, the 17th November 1949 ———— The Constituent Assembly of India met in the Constitution Hall, New Delhi, at Ten of the Clock, Mr. -

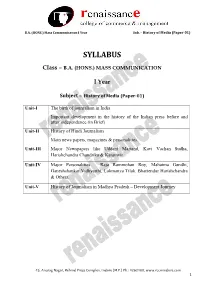

BA (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year

B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) SYLLABUS Class – B.A. (HONS.) MASS COMMUNICATION I Year Subject – History of Media (Paper-01) Unit-I The birth of journalism in India Important development in the history of the Indian press before and after independence (in Brief) Unit-II History of Hindi Journalism Main news papers, magazines & personalities. Unit-III Major Newspapers like Uddant Martand, Kavi Vachan Sudha, Harishchandra Chandrika & Karamvir Unit-IV Major Personalities – Raja Rammohan Roy, Mahatma Gandhi, Ganeshshankar Vidhyarthi, Lokmanya Tilak, Bhartendur Harishchandra & Others. Unit-V History of Journalism in Madhya Pradesh – Development Journey 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.A. (HONS.) Mass Communication I Year Sub. – History of Media (Paper-01) UNIT-I History of journalism Newspapers have always been the primary medium of journalists since 1700, with magazines added in the 18th century, radio and television in the 20th century, and the Internet in the 21st century. Early Journalism By 1400, businessmen in Italian and German cities were compiling hand written chronicles of important news events, and circulating them to their business connections. The idea of using a printing press for this material first appeared in Germany around 1600. The first gazettes appeared in German cities, notably the weekly Relation aller Fuernemmen und gedenckwürdigen Historien ("Collection of all distinguished and memorable news") in Strasbourg starting in 1605. The Avisa Relation oder Zeitung was published in Wolfenbüttel from 1609, and gazettes soon were established in Frankfurt (1615), Berlin (1617) and Hamburg (1618). -

Biography of Babarao Savarkar

Biography of Babarao Savarkar www.savarkar.org Preface Ganesh Damodar Savarkar was a patriot of the first order. Commonly known as Babarao Savarkar, he is the epitome of heroism that is unknown and unsung! He was the eldest of the four Savarkar siblings - Ganesh or Babarao; Vinayak or Tatyarao, Narayan or Balarao were the three Savarkar brothers; they had a sister named Maina or Mai who was married into the Kale family. Babarao was a great revolutionary, philosopher, writer and organizer of Hindus. The following account is largely an abridged English version of Krantiveer Babarao Savarkar, a Marathi biography written by DN Gokhale, Shrividya Prakashan, Pune, second edition, pp.343, 1979. Some part has been taken from Krantikallol (The high tide of revolution), a Marathi biography of Veer Vinayak Damodar (Tatyarao) Savarkar’s revolutionary life by VS Joshi; Manorama Prakashan, 1985. Details of the Cellular jail have been taken from Memorable Documentary on revolutionary freedom fighter Veer Savarkar by Prem Vaidya, Veer Savarkar Prakashan, 1997 and also from the website www.andamancellularjail.org. Certain portions dealing with Babarao’s warm relations with Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh founder Dr. Keshav Baliram Hedgewar have been translated from Dr. Hedgewar’s definitive Marathi biography by Narayan Hari Palkar; Bharatiya Vichar Sadhana, Pune, fourth edition, 1998. Pune, 28 May 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface ...........................................................................................1 1 Early childhood.......................................................................7 1.1 Babarao and Tatyarao: ......................................................................... 8 2 Initial Revolutionary Activities...............................................10 2.1 Liberation of the soul or liberation of the motherland? ........................ 10 2.2 Mitramela and Abhinav Bharat: ........................................................... 11 2.3 First-ever public bonfire of foreign goods: .......................................... -

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra