Exploring the Link Between Domestic Conflicts and Negotiation Failure in the Middle East

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18, No. 01 January-March 2002 Israel

The Marxist Volume: 18, No. 01 January-March 2002 Israel-Palestine Conflict: Sharonism Rampant Vijay Prashad 1. The Zeevi Invasion US President George W. Bush changed the rules of international engagement on the evening of 11 September 2001. In response to the horrible attacks on New York City and Washington DC, Bush rejected the slow wisdom of justice for the impatient brutality of revenge. “Either you are with us,” Bush said to the world community, “or you are against us.” Those who do not assist the United States government in its quest to uproot the forces of terror will themselves be seen as terrorists. On 5 October 2001, Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon sent tanks and troops of the Israeli Defense Force (IDF) into Hebron in the West Bank. The incursion into Palestinian Authority (PA) controlled land of what was once the Occupied Territories came as a result of an escalation of provocations from the Israeli government against the Palestinians. Sharon offered the same logic as Bush – either the PA is with the Israeli government in its attempt to repress all forms of militancy (now labeled terrorism) or else the PA is a legitimate target. If the Taliban can be overthrown to get Osama bin Laden and al-Qa’ida, then so can the PA. Even as PA chairman Yasser Arafat backed the US war against Afghanistan that began two days later, and even as radical Palestinians accepted this posture in the name of Palestinian unity, the IDF continued its onslaught. One provocation followed another.[i] The most important event that led to the current crisis was the IDF assassination of Abu Ali Mustafa, the head of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (the Marxist-Leninist formation from 1968 and, until February 2002, a key part of the Palestinian Liberation Organization, PLO). -

The Palestinians: Background and U.S

The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations Jim Zanotti Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs August 17, 2012 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34074 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations Summary This report covers current issues in U.S.-Palestinian relations. It also contains an overview of Palestinian society and politics and descriptions of key Palestinian individuals and groups— chiefly the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the Palestinian Authority (PA), Fatah, Hamas, and the Palestinian refugee population. The “Palestinian question” is important not only to Palestinians, Israelis, and their Arab state neighbors, but to many countries and non-state actors in the region and around the world— including the United States—for a variety of religious, cultural, and political reasons. U.S. policy toward the Palestinians is marked by efforts to establish a Palestinian state through a negotiated two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; to counter Palestinian terrorist groups; and to establish norms of democracy, accountability, and good governance within the Palestinian Authority (PA). Congress has appropriated assistance to support Palestinian governance and development amid concern for preventing the funds from benefitting Palestinian rejectionists who advocate violence against Israelis. Among the issues in U.S. policy toward the Palestinians is how to deal with the political leadership of Palestinian society, which is divided between the Fatah-led PA in parts of the West Bank and Hamas (a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization) in the Gaza Strip. Following Hamas’s takeover of Gaza in June 2007, the United States and the other members of the international Quartet (the European Union, the United Nations, and Russia) have sought to bolster the West Bank-based PA, led by President Mahmoud Abbas and Prime Minister Salam Fayyad. -

Palestinian Refugees in Syria During the Syrian Civil War

Teka Kom. Politol. Stos. Międzynar. – OL PAN, 2017, 12/1, 107–123 PALESTINIAN REFUGEES IN SYRIA DURING THE SYRIAN CIVIL WAR Marcin Szydzisz Institute of International Studies Faculty of Social Sciences University of Wroclaw Abstract: The article is an attempt to describe situation of Palestinian refugees during the Syrian Civil War. The author explains the attitude of the conflict’s main parties towards Palestinians. The paper also presents the stance of Palestinian parties (Hamas and PLO) and Palestinian refugees towards the Assad regime and rebels. Unfortunately, fights have been occurring in Palestinian camps, too (especially in the Yarmouk camp), so Palestinians are also victims of the conflict. Key words: Palestine, Palestinian refugees, Syria, Yarmouk camp During the 1948 war that established Israel’s existence, about 750,000 Arabs who had lived in Mandatory Palestine fled or were expelled from their homes. Almost 70,000 of them fled to Syria. They came mainly from the northern part of Palestine – Safad, Haifa, Acre, Tiberias, Nazareth and Jaffa. The majority of Palestinian refugees were settled along the border area with Israel. After the 1967 war, another 100,000 people, some of whom were Palestinian refugees, fled from the Golan Heights to other parts of Syria. According to UNRWA (the United Nation Relief and Works Agency for Palestinian Refugees) there are 560,000 registered Palestinian refugees1, almost three percent of the total Syrian population2. Some of these refugees lived in thirteen camps, nine of which are acknowledged by UNWRA (constituting about 30% of the Palestinian refugee population), while the other four camps are recognized only by Syrian govern- 1 http://www.unrwa.org/syria-crisis April 16, 2015. -

Lose Your Privileges Or Gain a Homeland? by Mohamed Gameel

Lose Your Privileges or Gain a Homeland? By Mohamed Gameel Hassan Asfour, senior Oslo-era negotiator for the Palestine Liberation Organization, discusses why the Oslo Accords were doomed and the next step: declaring an independent Palestinian nation s a leading Palestinian agitator and communist, Hassan Asfour, 69, has a history of political activism that eventually landed him a principal role at AOslo’s secret talks in 1993. Because of his Communist Party affiliations, Asfour moved from one Arab country to another. He left Jordan in 1969 for Iraq. He was expelled in 1975 to Syria, where he was arrested and spent sixteen months in jail. In 1977, Asfour was deported to Lebanon where he resided until the 1982 Israeli invasion and siege of Beirut. He eventually landed in Tunisia and became active in the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO). First Asfour was assigned by the Palestinian Communist Party in 1984 to coordinate the communists’ relationship with the PLO’s main political party, Fatah. Then, in 1987, Asfour was assigned to manage an organizational branch of the PLO. He became part of Yasser Arafat’s inner circle and was handed the job of coordinating the Palestinian delegation’s Madrid conference visit in 1991. Following Madrid, Asfour became one of only two PLO leaders to be selected as the Palestinians’ principal negotiator in crafting the Oslo Accords. Asfour next joined the post-Oslo Israeli–Palestinian talks as Secretary of Negotiations, a post he held from 1998 until he resigned in 2005. Despite the success of being part of the PLO negotiation team which gained significant concessions from the “enemy” (Israel), Asfour cannot ignore the mishaps that he feels caused Oslo’s “clinical death.” Seeing no future for the peace process and faulting the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) leadership, Asfour is an open critic of the PNA, and its incumbent president Mahmoud Abbas. -

Political Movements in the West Bank and Gaza

At a glance November 2015 Political movements in the West Bank and Gaza Political movements in the West Bank and Gaza are divided into factions of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) which accept the Oslo Accords, and non-PLO factions which reject a two state solution and Israel's right to exist. Fatah and Hamas are the largest Palestinian political movements. Background The Palestinian National Authority, or Palestinian Authority (PA), was granted limited rule in the Gaza Strip and parts of the West Bank in agreements signed in 1994 and 1995, following the Oslo Accords. The Palestinian Basic Law functions as a quasi-Constitution (attempts to draft a Permanent Constitution were abandoned). The PA has its own executive, legislative and judicial bodies, with Ramallah as its de facto seat. The executive branch has a President, currently Mahmoud Abbas (Fatah) and a Prime Minister, presently Rami Hamdallah. Legislative power is represented by the Palestinian Legislative Council (PLC), elected by Palestinians in the West Bank, the Gaza Strip and Jerusalem. The PLC is a unicameral parliament, consisting of 132 members, last elected to the PLC in 2006. The formation of a Hamas government led to international sanctions against the PA, and to subsequent negotiations between the two largest political movements, Fatah and Hamas, to form a unity government. The unity government formed in February 2007 collapsed shortly after, in June 2007, when Hamas seized control of the Gaza Strip. This led to dissolution of the government by the President; appointment of a Fatah-led 'caretaker' government in the West Bank; and suspension of the PLC. -

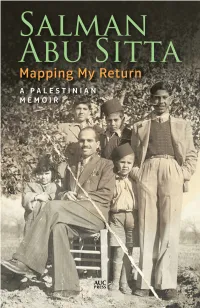

Mapping My Return

Mapping My Return Mapping My Return A Palestinian Memoir SALMAN ABU SITTA The American University in Cairo Press Cairo New York This edition published in 2016 by The American University in Cairo Press 113 Sharia Kasr el Aini, Cairo, Egypt 420 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10018 www.aucpress.com Copyright © 2016 by Salman Abu Sitta All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Exclusive distribution outside Egypt and North America by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd., 6 Salem Road, London, W2 4BU Dar el Kutub No. 26166/14 ISBN 978 977 416 730 0 Dar el Kutub Cataloging-in-Publication Data Abu Sitta, Salman Mapping My Return: A Palestinian Memoir / Salman Abu Sitta.—Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2016 p. cm ISBN 978 977 416 730 0 1. Beersheba (Palestine)—History—1914–1948 956.9405 1 2 3 4 5 20 19 18 17 16 Designed by Amy Sidhom Printed in the United States of America To my parents, Sheikh Hussein and Nasra, the first generation to die in exile To my daughters, Maysoun and Rania, the first generation to be born in exile Contents Preface ix 1. The Source (al-Ma‘in) 1 2. Seeds of Knowledge 13 3. The Talk of the Hearth 23 4. Europe Returns to the Holy Land 35 5. The Conquest 61 6. The Rupture 73 7. The Carnage 83 8. -

Mapping of the Arab Left Contemporary Leftist Politics in the Arab East

Edited by: Jamil Hilal and Katja Hermann MAPPING OF THE ARAB LEFT Contemporary Leftist Politics in the Arab East 2014 MAPPING OF THE ARAB LEFT Contemporary Leftist Politics in the Arab East Edited by Jamil Hilal and Katja Hermann 2014 The production of this publication has been supported by the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Regional Office Palestine. The content of this publication is the sole responsibility of the authors and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung Regional Office Palestine. Translation into English: Ubab Murad (with the exception of the text on Iraq). Turbo Design TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword .............................................................................................................6 Introduction: On the Self-definition of the Left in the Arab East ...................8 The Palestinian Left: Realities and Challenges ..............................................34 The Jordanian Left: Today’s Realities and Future Prospects .........................56 The Lebanese Left: The Possibility of the Impossible ....................................82 An Analysis of the Realities of the Syrian Left ............................................102 The Palestinian Left in Israel .........................................................................126 The Iraqi Left: Between the Shadows of the Past and New Alliances for a Secular Civic State .................................................................................148 MAPPING OF THE ARAB LEFT Contemporary -

1 the Making of The

THE MAKING OF THE PLO 1946: In May 1946, the first conference of Arab Kings and Presidents, according to the system of the League of Arab States, was held in Anshas near Cairo; the meeting decided: “Palestine is the heart of the Arab Group and the fate of Jerusalem is linked to the fate of the entire League of Arab States and what happens to the Arabs in Palestine affects all the Arab peoples… and the Arab countries and peoples have to protect the Arab features of Palestine”. 1948: Following the UN Partition Resolution 181,1947, the announcing of the end of the British Mandate, and the entry of the Arab troops into Palestine, the League of Arab States Political Commission decided on July 10, 1948, to establish a temporary Palestinian administration to manage the affairs of the Arab controlled territory. The first Palestinian conference was held in October 1948 in the presence of 90 figures representing the mayors of municipalities, heads of chambers of commerce, and representatives of national commissions and parties upon invitation by the Arab Higher Commission. The conference ratified the establishment of All-Palestine Government headed by Ahmad Hilmi Abdul Baqi; the members of the government consisted of the following: Jamal al-Husseini, Rajai al-Husseini, Awni Abdul Hadi, Akram Zuaiter, Dr. Hussein Fakhri al-Khalidi, Ali Hasna, Michel Abkarius, Yousef Sahyoun, and Amin Aqel. The conference decided that the flag of Palestine would be the flag of the Arab Revolt of 1916. Arab governments and the Arab League recognized the All-Palestine Government as soon as it was declared with the exception of Jordan. -

Official: Israeli Practices on Ground Weaken PNA Ability 17:34, March 20, 2008

Official: Israeli practices on ground weaken PNA ability 17:34, March 20, 2008 Yasser Abed Rabbo, member of Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) executive committee, accused Israel on Thursday for acting to weaken the ability of the Palestinian National Authority (PNA). "The Israeli government has been always seeking to beat the Palestinian National Authority and acting to weaken it," Abed Rabbo told the "Voice of Palestine" Radio. Abed Rabbo said the proof that Israel acts to weaken the PNA "is what has happened on the ground of blockade and siege in the West Bank and Gaza, in addition to settlement activities, arrests and raids on towns and villages." He added that Israel "is using all possible means to weaken the PNA, keeping in mind to avoid any international condemnation for such behavior." Meanwhile, Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat warned in a news conference in east Jerusalem on Wednesday that if a peace agreement is not reached by the end of 2008, the PNA might collapse. "Israel apparently doesn't need a Palestinian partner to achieve a just peace," Abed Rabbo said, adding "Israel wants to see the Palestinians divided in order to impose temporary solutions to win more time." Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert stated on Monday that his government is not intending to stop construction of settlement, a main obstacle to Palestinian-Israeli negotiations. In early March, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas temporarily suspended the peace talks with Israel after an Israeli offensive in the Hamas-controlled Gaza Strip killed more than 120 Palestinians. "Source:Xinhua" . -

The Palestinians: Background and U.S

The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations (name redacted) Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs February 10, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov RL34074 The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations Summary This report covers current issues in U.S.-Palestinian relations. It also contains an overview of Palestinian society and politics and descriptions of key Palestinian individuals and groups— chiefly the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the Palestinian Authority (PA), Fatah, Hamas (a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization), and the Palestinian refugee population. The “Palestinian question” is important not only to Palestinians, Israelis, and their Arab state neighbors, but to many countries and non-state actors in the region and around the world—including the United States—for a variety of religious, cultural, and political reasons. U.S. policy toward the Palestinians is marked by efforts to establish a Palestinian state through a negotiated two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict; to counter Palestinian terrorist groups; and to establish norms of democracy, accountability, and good governance. Congress has appropriated assistance to support Palestinian governance and development while trying to prevent the funds from benefitting Palestinians who advocate violence against Israelis. Since the signing of the Oslo Accord in 1993, Congress has committed more than $5 billion in bilateral assistance to the Palestinians, over half of it since mid-2007. Among the issues in U.S. policy toward the Palestinians is how to deal with the political leadership of Palestinian society. Although Fatah and Hamas agreed to the June 2014 formation of a consensus PA government appointed by Fatah head and PA President Mahmoud Abbas, Hamas retains de facto control over security in the Gaza Strip, despite forswearing formal responsibility. -

The Palestinians: Background and U.S

The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations Jim Zanotti Analyst in Middle Eastern Affairs January 8, 2010 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34074 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Palestinians: Background and U.S. Relations Summary This report provides an overview of current issues in U.S.-Palestinian relations and. It also contains an overview of Palestinian society and politics and descriptions of key Palestinian individuals and groups—chiefly the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), the Palestinian Authority (PA), Fatah, Hamas, and the Palestinian refugee population. For more information, see the following: CRS Report RS22967, U.S. Foreign Aid to the Palestinians, by Jim Zanotti; CRS Report R40664, U.S. Security Assistance to the Palestinian Authority, by Jim Zanotti; CRS Report R40092, Israel and the Palestinians: Prospects for a Two-State Solution, by Jim Zanotti, Israel and the Palestinians: Prospects for a Two-State Solution, by Jim Zanotti; and CRS Report RL33530, Israeli-Arab Negotiations: Background, Conflicts, and U.S. Policy, by Carol Migdalovitz. The “Palestinian question” is important not only to Palestinians, Israelis, and their Arab state neighbors, but to many countries and non-state actors in the region and around the world— including the United States—for a variety of religious, cultural, and political reasons. U.S. policy toward the Palestinians since the advent of the Oslo process in the early-1990s has been marked by efforts to establish a Palestinian state through a negotiated two-state solution to the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, counter Palestinian terrorist groups, and establish norms of democracy, accountability, and good governance within the PA. -

Fact-Finding As a Peace Negotiation Tool—The Mitchell Report and the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process

Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review Volume 24 Number 3 Article 1 6-1-2002 Fact-Finding as a Peace Negotiation Tool—The Mitchell Report and the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process Arthur Lenk Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Arthur Lenk, Fact-Finding as a Peace Negotiation Tool—The Mitchell Report and the Israeli-Palestinian Peace Process, 24 Loy. L.A. Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 289 (2002). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/ilr/vol24/iss3/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LOYOLA OF LOS ANGELES INTERNATIONAL AND COMPARATIVE LAW REVIEW VOLUME 24 JUNE 2002 NUMBER3 Fact-Finding as a Peace Negotiation Tool- The Mitchell Report and the Israeli- Palestinian Peace Process ARTHUR LENK* I. INTRODUCTION The peace process between the Israelis and the Palestinians requires creative concepts for conflict resolution. The "Oslo" process, which began as a series of discussions in Norway among academia, created a full range of legal and social relations between the Israelis and the Palestinians. 1 It used a range of differing methods and creativity to deal with seemingly irreconcilable issues between the parties. 2 The basic concept of the process was to begin with the "easier" issues and then gradually build a trusting * Arthur Lenk is an attorney in the Legal Adviser's Office in Israel's Ministry of Foreign Affairs.