What Climate Change Means for Louisiana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sedimentation Patterns Within the Atchafalaya Basin and Morganza Spillway Before and After the Lower Mississippi Flood of 2011

Sedimentation Patterns Within the Atchafalaya Basin and Morganza Spillway Before and After the Lower Mississippi Flood of 2011. Edward Schenk and Cliff Hupp Daniel E. Kroes US Geological Survey US Geological Survey National Research Program – Reston, VA Louisiana Water Science Center Morganza Spillway during the 2011 release 2011 Major Flood Peaks Morganza Spillway Modern Atchafalaya Basin Atchafalaya River, mainstem • Average annual discharge of 6410 m3/s (5th largest in U.S.). • Receives about 25% of the Mississippi River flow annually and all of the Red River flow. • Conducts as much as 35% of the suspended- and 60% of the bed-sediment load of the Mississippi River. • The Basin wetland (5670 km2) is about 70% forested (largest contiguously forested wetland in the U.S); the remainder is open water and marshland. • The Basin is about 160 km long and 20 to 30 km wide, which discharges into the Gulf of Mexico (deltaic sedimentation). • Forests are of three main communities; 1. typical bottomland hardwoods on levees and transitional areas, 2. cypress/tupelo stands in backswamps, 3. successional, predominantly willow stands on recently aggraded bars (common). The Atchafalaya Basin is the Red River Mississippi only sizable semi natural riparian area along the Mississippi River below the confluence of the B Ohio River. (remaining) A Annual Sequestration: Atchafalaya Sediment 4.3 billion kg Organic Material 435 million kg Total Carbon 175 million kg C D Strong case for stream restoration, and reconnection of streamflow to the riparian zone Gulf -

Wild Turkey Movements During Flooding After Opening of the Morganza Spillway, Louisiana Author(S): Michael J

Wild Turkey Movements During Flooding After Opening of the Morganza Spillway, Louisiana Author(s): Michael J. Chamberlain, Michael E. Byrne, Norman J. Stafford III, Kevin L. Skow and Bret A. Collier Source: Southeastern Naturalist, 12(1):93-98. Published By: Eagle Hill Institute DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1656/058.012.0108 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1656/058.012.0108 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/ page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non- commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. 2013 SOUTHEASTERN NATURALIST 12(1):93–98 Wild Turkey Movements During Flooding After Opening of the Morganza Spillway, Louisiana Michael J. Chamberlain1,*, Michael E. Byrne2,3, Norman J. Stafford III4, Kevin L. Skow5, and Bret A. Collier5 Abstract - The opening of the Morganza Spillway in Louisiana on 18 May 2011 to relieve KLVWRULF ÀRRGLQJ DORQJ WKH ORZHU 0LVVLVVLSSL ULYHU VXEVHTXHQWO\ LQXQGDWHG WKRXVDQGV of acres of bottomland forest in the Atchafalaya basin. -

Sediment and Nutrient Trapping on the Morganza Spillway During the 2011 Mississippi River Flood

SEDIMENT AND NUTRIENT TRAPPING ON THE MORGANZA SPILLWAY DURING THE 2011 MISSISSIPPI RIVER FLOOD. Daniel E. Kroes, Research Ecologist U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected]; Edward R Schenk; Gregory B Noe; Adam J Benthem The 2011 Mississippi River Flood resulted in the opening of the Morganza Spillway for the second time since its construction in 1954. The opening of the Spillway structure released 7.6 km3 of water through agricultural and forested lands into the Morganza Floodway and the Atchafalaya River Basin (the Basin). This volume represented 5.5 % of the Mississippi River (MR) discharge and 14% of the total discharge through the Basin during the Spillway operation and 1.1 % of the MR and 3.3% of the Basin 2011 water year discharge. During the release there was a net sediment deposition of 0.77 Tg over the 500 km2 Morganza Spillway and 0.26 Tg was eroded from behind the Spillway structure. The majority of deposition (63 %) occurred in the Forebay (upstream of the structure) and within 4 km downstream of the Spillway structure with minor deposition on the rest of the Floodway. There was a net deposition of 2,600 Mg of nitrogen (N) and 536 Mg of phosphorous (P), during the diversion and was equivalent to 0.17% N and 0.33% P of the 2011 annual MR load. Deposited sediment (84%) was composed of particles that were finer than 50 μm. Median deposited sediment grain size at the start of the Forebay was 13 μm and decreased to 2 μm 15 km downstream of the Spillway structure. -

1 21 2013 Mississippi River Channel Response to the Bonnet Carré

Journal of Hydrology 477 (2013) 104–118 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Journal of Hydrology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhydrol Mississippi River channel response to the Bonnet Carré Spillway opening in the 2011 flood and its implications for the design and operation of river diversions ⇑ Mead A. Allison a, , Brian M. Vosburg b, Michael T. Ramirez a, Ehab A. Meselhe c a University of Texas Institute for Geophysics, University of Texas, 10100 Burnet Road, (R2200) Austin, TX 78758-4445, USA b Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, Baton Rouge, LA 70804-4027, USA c The Water Institute of the Gulf, Baton Rouge, LA 70804, USA article info summary Article history: The large Mississippi River flood in 2011 was notable in the lowermost Louisiana, USA reach for requiring Received 24 August 2012 operation of several flood control structures to reduce stress on artificial levees: the largest diversion Received in revised form 2 November 2012 went through the gated Bonnet Carré Spillway, which was opened for 42 days in May and June. The Accepted 5 November 2012 removal of approximately 20% of the total flood discharge from the river provided an opportunity to Available online 22 November 2012 examine the impact of large water diversion on the sediment transport capacity of large rivers. This manuscript was handled by Geoff Syme, Editor-in-Chief Boat-based, acoustic and water and bed sampling surveys were conducted in the Mississippi River channel adjacent to the Spillway immediately prior to the opening of the structure, at full capacity, and immediately following (June 2011) and 1 year after (June 2012) closure. -

Ecosystem Effects in the Lower Mississippi River Basin

Ecosystem Effects in the Lower Mississippi River Basin Chapter L of 2011 Floods of the Central United States Professional Paper 1798–L U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. View of flooding from Nebraska City, Nebraska, looking east across the Missouri River, August 2, 2011. Photograph by Robert Swanson, U.S. Geological Survey (USGS). Ecosystem Effects in the Lower Mississippi River Basin By D. Phil Turnipseed, Yvonne C. Allen, Brady R. Couvillion, Karen L. McKee, and William C. Vervaeke Chapter L of 2011 Floods of the Central United States Professional Paper 1798–L U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior SALLY JEWELL, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2014 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Turnipseed, D.P., Allen, Y.C., Couvillion, B.R., McKee, K.L., and Vervaeke, W.C., 2014, Ecosystem effects in the Lower Mississippi River Basin: U.S. -

Group Tour Wednesday, January 17, 2018 11:30 AM – 5:00 PM

Tours Group Tour Wednesday, January 17, 2018 11:30 AM – 5:00 PM Old River Control Structure The Old River Control structures are operated to maintain the distribution of flow between the Mississippi River and the Atchafalaya River, and also prevent the Atchafalaya River from capturing the flow of the Mississippi River. The Old River Control project consists of several large engineering structures. These structures include the Old River Low Sill and Overbank Structures that began operation in 1962; the Old River Lock completed in 1963; and the Auxiliary Structure built in 1986. Morganza Spillway Control Structure The Morganza Spillway or Morganza Control Structure is a flood-control structure in the U.S. state of Louisiana along the western bank of the lower Mississippi River at river mile 280, near Morganza in Pointe Coupee Parish. The spillway stands between the Mississippi and the Morganza Floodway, which leads to the Atchafalaya Basin and the Atchafalaya River in south- central Louisiana. Its purpose is to divert water from the Mississippi River during major flood events by flooding the Atchafalaya Basin, including the Atchafalaya River and the Atchafalaya Swamp. The spillway and adjacent levees also help prevent the Mississippi from changing its present course through the major port cities of Baton Rouge and New Orleans to a new course down the Atchafalaya River to the Gulf of Mexico. The Morganza Spillway, operated by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, was opened during the 1973 and 2011 Mississippi River floods Spouses Tour Thursday, January 18, 2018 Board the bus for a short ride south of downtown to Magnolia Mound Plantation. -

![ORDER GRANTING MOTION to INTERVENE FILED by the STATE of LOUISIANA BEFORE the COURT Is the [30] Motion to Intervene Filed By](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1666/order-granting-motion-to-intervene-filed-by-the-state-of-louisiana-before-the-court-is-the-30-motion-to-intervene-filed-by-2951666.webp)

ORDER GRANTING MOTION to INTERVENE FILED by the STATE of LOUISIANA BEFORE the COURT Is the [30] Motion to Intervene Filed By

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF MISSISSIPPI SOUTHERN DIVISION MICHAEL D. WATSON, JR., in his Official Capacity as Secretary of State and Trustee of the Public Tidelands Trust PLAINTIFF v. CAUSE NO. 1:19cv989-LG-RHW U.S. ARMY CORPS OF ENGINEERS, et al. DEFENDANTS ORDER GRANTING MOTION TO INTERVENE FILED BY THE STATE OF LOUISIANA BEFORE THE COURT is the [30] Motion to Intervene filed by the State of Louisiana, ex rel. Jeff Landry, Attorney General of the State of Louisiana, by and through the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority and the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority Board. None of the current parties to the lawsuit have filed a response to the Motion. After reviewing the Motion, the record in this matter, and the applicable law, the Court finds that the Motion to Intervene should be granted. BACKGROUND The Bonnet Carré Spillway was constructed in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana, as part of the Mississippi River and Tributaries Project. It was designed to divert water from the Mississippi River into Lake Pontchartrain in an effort to prevent flooding. After entering Lake Pontchartrain, the water diverted by the Spillway flows into the Mississippi Sound. The plaintiff, who filed this lawsuit in his capacity as Secretary of State and Trustee of the Public Tidelands Trust for the State of Mississippi, has sued the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and General Todd T. Semonite in his official capacity as commanding general of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The plaintiff has also sued the Mississippi River Commission and General R. -

MR&T: Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System

Click to edit Master title style Atchafalaya River Basin Restoration and Enhancement Task Force committed to our coast 1 Mississippi River & Tributaries (MR&T): 70/30 Split Response to the Geomorphology of Old River • The Atchafalaya – a distributary of the Mississippi River – provides a shorter steeper path to the Gulf of Mexico than the current Mississippi path. • The Corps of Engineers regulates flow through the Old River Control Structure at a 70-30 split • 70 percent of the combined flow of the Red and Mississippi rivers • 30 percent passes down the Atchafalaya. • Sediment and Water Budgets developed by the LCA Science Advisory Panel revealed that sediment is not distributed in a likewise fashion. 2 MR&T: Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System (ABFS) Jadwin Plan: Project Design Flood • authorized by the 1928 Flood Control Act • system of public works within the lower Mississippi Valley providing flood risk management and a stable, efficient navigation channel • Uses levees and floodwalls, floodways, channel improvements and stabilization all to ensure that the Project Design Flood can safely pass limiting damages • The Morganza Spillway is meant to divert 600,000 cfs from downstream communities on the Mississippi River and alleviate stress on downstream levees. 3 FLOODWAY Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System PARISH BOUNDARY Lies within eight parishes: 1.Assumption 2.Avoyelles 3.Iberia 4.Iberville 5.Pointe Coupee 6.Saint Landry 7.Saint Martin 8.Saint Mary 4 Atchafalaya Basin Floodway System Upper Floodway Water Management Units 1. Alabama Bayou 7. Cocodrie 2. Lake Henderson Swamp 3. Werner 8. Pigeon Bay 4. Bayou des 9. Beau Bayou Glaises 10. -

In the United States Court of Federal Claims

In the United States Court of Federal Claims No. 11-389L (Filed: August 20, 2013) _________ DENNIS J. QUEBEDEAUX, on behalf of * himself and all other similarly situated * persons and entities, * Takings case; Motion to dismiss under * RCFC 12(b)(6); Morganza Floodway – Plaintiffs, * release of water; Iqbal/Twombly – pleading standard; Sponenbarger doctrine; Tort vs. * takings; Rejection of bright line test in favor v. * of multi-factored approach; Motion denied. * THE UNITED STATES, * * Defendant. * _________ OPINION __________ Richard Lyle Coffman, The Coffman Law Firm, Beaumont, TX, for plaintiffs. Joshua Pratt Wilson, Environment and Natural Resources Division, United States Department of Justice, Washington, D.C., with whom was Assistant Attorney General Ignacia S. Moreno, for defendant. ALLEGRA, Judge: This takings case is before the court on defendant’s motion to dismiss the complaint pursuant to RCFC 12(b)(6). Plaintiffs own land in the Morganza Floodway and Atchafalaya River basin, part of the Lower Mississippi River Valley. They seek just compensation under the Fifth Amendment for an alleged takings associated with the inundation of their property with water diverted from the Mississippi River.1 Based on its careful review of the briefs, and oral argument, the court hereby DENIES defendant’s motion. 1 Plaintiffs seek certification of a class of similar-situated property holders. The court has deferred consideration of class certification under RCFC 23 until resolution of this motion. I. BACKGROUND2 The facts required here are relatively simple and few. The Morganza Floodway, which includes the Morganza Spillway, is part of the Mississippi River & Tributaries Project (the MR&T Project) – the comprehensive federal system of levees, flood control channels, dams, pumping stations, and reservoirs designed to control floods on the Mississippi River.3 The Morganza Spillway is a structure on the Mississippi River that sits at the head of the Morganza Floodway. -

Major Flooding and Persistent Drought Occurred at the Same Time in May 2011

NWS FORM E-5 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE HYDROLOGIC SERVICE AREA (HSA) (11-88) NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION (PRES. by NWS Instruction 10-924) NATIONAL WEATHER SERVICE NEW ORLEANS/BATON ROUGE, LA REPORT FOR: MONTHLY REPORT OF HYDROLOGIC CONDITIONS MONTH YEAR MAY 2011 SIGNATURE TO: Hydrometeorological Information Center, W/OH2 NOAA / National Weather Service KENNETH GRAHAM 1325 East West Highway, Room 7230 METEOROLOGIST-IN-CHARGE Silver Spring, MD 20910-3283 DATE JUNE 15, 2011 When no flooding occurs, include miscellaneous river conditions, such as significant rises, record low stages, ice conditions, snow cover, droughts, and hydrologic products issued (NWS Instruction 10-924) An X inside this box indicates that no flooding occurred within this hydrologic service area. ...Major Flooding and Persistent Drought Occurred at the Same Time in May 2011... The phenomenon of flooding during a drought was prominent in May. Since most of the heavier rains during April missed this region, soil deficits were exacerbated across southeastern Louisiana, southwestern Mississippi, and coastal Mississippi. Soil conditions further deteriorated during May, after only a few periods of heavy rainfall developed across the area. At the same time, spring rainfall and snowmelt over the northern and central United States produced major flooding along the Mississippi River and eventually over much of the Atchafalaya River Basin. The Spring Flood of 2011 was among the most damaging flood events in the last century and comparable to the Mississippi River Floods of 1927, 1983, and 1993. As snow and ice melted, flooding first developed in March and continued into May on the Atchafalaya River at Morgan City, LA. -

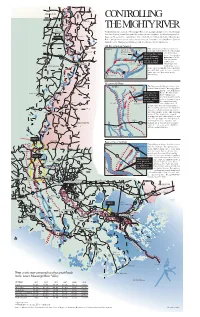

Controlling the Mighty River

ARKANSAS CONTROLLING Anguilla Oak Grove 65 THE MIGHTY RIVER 61 Lake Providence Control structures on the Mississippi River are designed to preserve life through the river basin as well as provide a systematic response to alleviate possible Onward LEVEES flooding during severe conditions. Three structures exist on the lower Mississippi River, and all have been called into service at least once: the Old River Control Complex, the Morganza Spillway and the Bonnet Carré Spillway. Old River Control Complex 3 INSET 1 Sidney A. Over bank This complex uses four structures to Murray Jr. structure distribute flows between the Mississippi Redwood Delhi Hydroelectric and Atchafalaya Station Mississippi River water diverted primarily rivers. The complex maintains a 70/30 20 Outflow channel though these two Red River flow distribution 17 structures into the Low sill Atchafalaya River between the Vicksburg Old Ri structure Mississippi and Upper ve Auxiliary 65 r structure Atchafalaya rivers, LOUISIANA 27 R respectively, at Old River and can safely L Old iv o w er er Levee pass 620,000 cubic feet per second of water from the Mississippi to the 61 Atchafalaya Mississippi River Atchafalaya. 4 River Morganza Spillway INSET 2 The Morganza Spillway is designed to Port Gibson r e transfer flows from the Mississippi River v A i into the east Atchafalaya tc R r h i e a sissipp Basin. The Mississippi Sicily Island iv f s Mississippi River i R a Levee i p l River Commission 15 ip a M water diverted s y is a through control president would normally s R s make a decision to open i structure and into i v M e the spillway the control structure Fayette r 28 Melville Morganza when flows reach 1.5 61 million cubic feet per second at Red River Landing, just above the Morganza 84 structure, with data indicating that the Vidalia Natchez river will continue to rise. -

The Atchafalaya National Heritage Area

The Atchafalaya National Heritage Area Selected Level 0 Cultural Landscape Assessments 2010 Suzanne Turner Associates, LLC Consultant for Historic Landscapes 635 Louisiana Avenue, Baton Rouge, Louisiana 70802 Suzanne Turner, FASLA John Welch, RLA Nick Musso, ASLA This study was initiated by the State of Louisiana, Department of Culture, Recreation, and Tourism, in order to fulfill federal mandates related to funding and designation of the Atchafalaya National Heritage Area. Debra Credeur, Executive Director of the Atchafalaya National Heritage Area spearheaded the selection of the cultural resources that were surveyed, in order to represent the region in areal extent, cultural resource type, and importance of the different resources in the basin. The primary resources for the site selection process were 1) the National Park Service Cultural Landscape Management Guideline, and 2) a Heritage Resource Screening Process used by a similar heritage area with an approved Management Plan. This process selects resources under the broader categories of cultural, historical, natural and recreational, which is consistent with our enabling legislation, and then breaks these categories down further into themes. The National Park Service Planning Team then consulted with the State of Louisiana Architectural Historian and National Register Coordinator to select National Historic Landmarks and other cultural landscapes that reflect heritage area themes. Effort was made to have all types of landscapes represented as well as all 14 parishes. The individual assessments will be used as references for similar types of resources for projects in the future. Suzanne Turner Associates was contracted to conduct a “Level 0” assessment of selected properties within the Atchafalaya National Heritage Area, and to document the basic history of the site, construct a bibliography and partial literature review for each subject property, and document existing threats to the cultural assets of the region.