Conclusion a Catholic Women's Liberal Arts College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Blessings

SPRING 2021 School Sisters of Notre Dame Atlantic-Midwest Province MEMORIES AND BLESSINGS OF LEADERSHIP In March 2016, Delegates representing all parts of the Atlantic- Midwest Province gathered together in Rochester, NY to elect provincial leadership for the years 2016–2020. The Leadership Blessings is a publication for Team is elected by our Sisters and is currently composed of a The School Sisters of Notre Dame are part of an family, friends and benefactors of Provincial and five Councilors. As each Councilor was elected, the School Sisters of Notre Dame. she chose a scripture passage to mark her years of leadership. international congregation. They currently minister in SSNDs in the Atlantic-Midwest Each of us carried these words to Installation Day, July 9, Province express their mission of 30 countries. “Our internationality challenges us 2016, held at Villa Notre Dame in Wilton, CT. There we stood unity through education, which ay leadership on the altar facing our Sisters, professing our gratitude to our enables persons to reach the fullness to witness to unity in a divided world; to discover foundress, Mother Theresa Gerhardinger, and to the many of their potential. “Urged by the love be for us a true adventure of Christ, we choose to express our women of our congregation who had gone before us, who unsuspected ways of sharing what we have, especially of growth." mission through ministry directed M learned to trust in God and who dared to risk all for the sake of the mission. toward education. For us, education with the poor and marginalized; and to search for new means enabling persons to reach — John O’Donahue As a newly elected Council, we pledged to continue the work of Embracing the Future. -

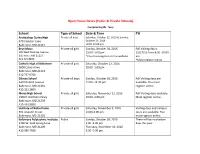

Open House Dates 2016-2017

Open House Dates (Public & Private Schools) Compiled by Ms. Terry School Type of School Date & Time FYI Archbishop Curley High Private-all boys Saturday, October 22, 2016 & Sunday, 3701 Sinclair Lane October 23, 2016 Baltimore, MD 21213 10:00-12:00 pm Bryn Mawr Private-all girls Sunday, October 30, 2016 Fall Visiting day is 109 West Melrose Avenue 11:00 -1:00 pm 11/17/16 from 8:30 -10:00 Baltimore, MD 21210 *You must register on the website am 443.323.8800 *Must register online Catholic High of Baltimore Private-all girls Saturday, October 22, 2016 2800 Edison Hwy 10:00- 1:00 pm Baltimore, MD 21213 410.732.6200 Gilman School Private-all boys Sunday, October 30, 2016 Fall Visiting days are 5407 Roland Avenue 11:00 -12:30 pm available. You must Baltimore, MD 21210 register online 410.323.3800 Mercy High School Private-all girls Saturday, November 12, 2016 Fall Visiting days available. 1300 E. Northern Pkwy 10:00 -2:00 pm Must register online. Baltimore, MD 21239 410.433.8880 Institute of Notre Dame Private-all girls Saturday, November 5, 2016 Visiting days and Campus 901 Aisquith Street 11:00-2:00 pm tours are available. You Baltimore, MD 21202 must register online. Baltimore Polytechnic Institute Public Sunday, October 30, 2016 There will be no shadow 1400 W. Cold Spring Lane 1:00 -3:00 pm days this year. Baltimore, MD 21209 Thursday, November 10, 2016 410.396.7030 5:30 -7:30 pm Baltimore City College Public Wednesday, October 12, 2016 3220 The Alameda Thursday, November 15, 2016 Baltimore, MD 21218 6:00 -8:00 pm 410.396.6557 Western High School Public-all girls Wednesday, October 19, 2016 Shadow dates are available 4600 Falls Road 5:30 -7:30 pm October-December by Baltimore, MD 21209 Saturday, November 12, 2016 appointment. -

AIMS Member Schools

AIMS Member Schools Aidan Montessori School Barnesville School of Arts & Sciences Beth Tfiloh Dahan Community School 2700 27th Street NW 21830 Peach Tree Road 3300 Old Court Road Washington DC 20008‐2601 P.O. Box 404 Baltimore MD 21208 (202) 387‐2700 Barnesville MD 20838‐0404 (410) 486-1905 www.aidanschool.org (301) 972‐0341 www.bethtfiloh.com/school Grades: 18 Months‐Grade 6 www.barnesvilleschool.org Grades: 15 Months‐Grade 12 Head of School: Kevin Clark Grades: 3 Years‐Grade 8 Head of School: Zipora Schorr Enrollment: 184 (Coed) Head of School: Susanne Johnson Enrollment: 936 (Coed) Religious Affiliation: Non‐sectarian Enrollment: 130 (Coed) Religious Affiliation: Jewish County: DC Religious Affiliation: Non-sectarian County: Baltimore DC’s oldest Montessori, offering proven County: Montgomery Largest Jewish co‐educational college‐ pedagogy and beautiful urban setting Integrating humanities, art, math, preparatory school in the Baltimore area science in a joyous, supportive culture Archbishop Spalding High School The Boys' Latin School of Maryland 8080 New Cut Road Barrie School 822 West Lake Avenue Severn MD 21144‐2399 13500 Layhill Road Baltimore MD 21210‐1298 Silver Spring MD 20906 (410) 969‐9105 (410) 377‐5192 (301) 576‐2800 www.archbishopspalding.org www.boyslatinmd.com www.barrie.org Grades: 9‐12 Grades: 18 Months‐Grade 12 Grades: K‐12 President: Kathleen Mahar Head of School: Jon Kidder Head of School: Christopher Post Enrollment: 1252 (Coed) Enrollment: 280 (Coed) Enrollment: 613 (Boys) Religious Affiliation: Roman Catholic -

SEVP Certified Schools June 8, 2016 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc

Updated SEVP Certified Schools June 8, 2016 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 424 Aviation 424 Aviation N Y Miami FL 103705 - A - A F International School of Languages Inc. A F International of Westlake Village Y N Westlake Village CA 57589 A F International School of Languages Inc. A F International College Y N Los Angeles CA 9538 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Kirksville Coll of Osteopathic MedicineY N Kirksville MO 3606 Aaron School Aaron School Y N New York NY 114558 Aaron School Aaron School - 30th Street Y N New York NY 159091 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. ABC Beauty Academy, INC. N Y Flushing NY 95879 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC ABC Beauty Academy N Y Garland TX 50677 Abcott Institute Abcott Institute N Y Southfield MI 197890 Aberdeen School District 6-1 Aberdeen Central High School Y N Aberdeen SD 36568 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Abiding Savior Lutheran School Y N Lake Forest CA 9920 Abilene Christian Schools Abilene Christian Schools Y N Abilene TX 8973 Abilene Christian University Abilene Christian University Y N Abilene TX 7498 Abington Friends School Abington Friends School Y N Jenkintown PA 20191 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Tifton Campus Y N Tifton GA 6931 Abraham Joshua Heschel School Abraham Joshua Heschel School Y N New York NY 106824 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis SchoolY Y New York NY 52401 Abundant Life Christian School Abundant Life Christian School Y N Madison WI 24403 ABX Air, Inc. -

ED269866.Pdf

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 269 866 EA 018 406 AUTHOR Yeager, Robert J., Comp. TITLE Directory of Development. INSTITUTION National Catholic Educational Association, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 86 NOTE 34p. AVAILABLE FROMPublication Sales, National Catholic Educational Association, 1077 30th Street, N.W., Suite 100, Washington, DC 20007-3852 ($10.95 prepaid). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Administra"orsi 4.Catholic Schools; Elementary Secondary ,ducatien; *Institutional Advancement; National Surveys; Postsecondary Education IDENTIFIERS Development Officers ABSTRACT This booklet provides a listing of all the Catholic educational institutions that responded to a nationalsurvey of existing insti utional development provams. No attemptwas made to determine the quality of the programs. The information is providedon a regional basis so that development personnel can mo.s readily make contact with their peers. The institutions are listed alphabetically within each state grouping, and each state is listed alphabetically within the six regions of the country. Listingsare also provided for schools in Belgium, Canada, Guam, Italy, and Puerto Rico. (PGD) *********************************.************************************* * Reproductions supplied by =DRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * ***********************0*****************************************1***** £11 Produced by The Office of Development National Catholic Education Association Compiled by -

Final Partnership Release on Letterhead

P.O.Box 840 Pasadena, Maryland 21123 Phone: (410) 768.2595 Fax: (410) 768.5471 www.iaamsports.com FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE FOR INFORMATION MEMBER SCHOOLS September 25, 2012 Susan Thompson - IAAM 410.768.2595 Annapolis Area Christian School Joyce Cahalan - TSM Archbishop Spalding High School 410.337.7900 Baltimore Lutheran School IAAM FORMS PARTNERSHIP WITH TOWSON ORTHOPAEDIC Beth Tfiloh School ASSOCIATES/TOWSON SPORTS MEDICINE Bryn Mawr School Girls' athletic league aims to promote injury prevention and care The Catholic High School of Baltimore The IAAM, (Interscholastic Athletic Association of Maryland) is pleased to Chapelgate Christian Academy announce the formation of a partnership with Towson Orthopaedic Friends School Associates & Towson Sports Medicine. The collaboration, which brings Garrison Forest School together two organizations serving young female athletes, is aimed at injury prevention and education. Glenelg Country School Indian Creek School The diverse IAAM league includes 31 co-ed and female-only independent schools across Maryland who share a common commitment to athletics Institute of Notre Dame as an extension of the educational process. Towson Sports Medicine John Carroll School (TSM), a division of Towson Orthopaedic Associates, has a longstanding Key School commitment to high school athletes and others in the area seeking the services of a physical therapy rehabilitation center. Maryvale Preparatory School McDonogh School “The IAAM seeks to partner with those organizations and companies who Mercy High School share our goals to support and to advance young women and their athletic experiences," said Sue Thompson, Executive Director, IAAM. Mount de Sales Academy "Towson Orthopaedic Associates/Towson Sports Medicine shares our Notre Dame Preparatory School objectives specifically, providing support and professional medical Oldfields School attention to our female athletes. -

R00A03, MSDE Funding for Educational Organizations

R00A03 Funding for Educational Organizations Maryland State Department of Education Response to the Analyst’s Review and Recommendations House Education and Economic Development Subcommittee – January 26, 2017 Senate Education, Business, and Administration Subcommittee – January 27, 2017 Karen B. Salmon, Ph.D. State Superintendent of Schools The Maryland State Department of Education (MSDE) welcomes the opportunity to respond to the items noted in the budget analysis. The analysis provides a comprehensive overview of the goals and activities of the Funding for Educational Organizations budget. As noted in the analysis, this budget provides grants to organizations with unique operations through five budgetary programs: • The Maryland School for the Blind • Blind Industries and Services of Maryland • State Aided Educational Institutions • Aid to Nonpublic Schools • Broadening Options and Opportunities for Students Today (BOOST) With regard to the specific issues and recommendations noted in the analysis: Maryland School for the Blind (MSB) MSB should comment on how it has grown the Outreach Program and how large it expects it to grow. MSB should explain why the capital draw for fiscal 2017 is so large and whether projects from fiscal 2016 were postponed to be funded in fiscal 2017. MSDE Response: The Maryland School for the Blind will address the questions and recommendations noted in the DLS analysis pertaining to MSB. Blind Industries and Services of Maryland (BISM) DLS Recommendation: Adopt the following narrative: In the annual Managing for Results (MFR) submissions, Blind Industries and Services of Maryland (BISM) reports measures on hours of training provided in blindness skills to adult and senior citizens who are blind or low vision. -

ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY of the CATHOLIC GERMANS in MARYLAND by CHARLES R

ECCLESIASTICAL HISTORY OF THE CATHOLIC GERMANS IN MARYLAND By CHARLES R. GELLNER There is a rather sharply defined be- requesting a German church, German ginning to the development of Catholic catechism and even a German bishop. German church life in Maryland. Be- An unfavorable reply was given him on fore 1840 not much of importance was each count. Rome obviously preferred accomplished by the Catholics of Ger- to leave the solution of the difficulty in man extraction but in that year they Bishop Carroll's hands. Meanwhile, were committed to the charge of the Reuter returned to Baltimore and with Redemptorists who initiated almost all his fellow-Germans established, October the constructive measures undertaken. 11, 1799, the first Catholic German Finally, since the Germans were en- church in Baltimore, at Park Avenue trusted to the Redemptorists, the growth and Saratoga Street, dedicated to St.. of the German parishes is intimately John the Evangelist.1 Unfortunately, associated with the history of that order the whole movement was schismatic.2 in Maryland, and more especially in The breach was healed, however, by Baltimore. By the time the parishes 1805 when the parish returned to the nurtured by the Redemptorists passed jurisdiction of the bishop and Father into the hands of diocesan or other Reuter was replaced by the Reverend clergy the Americanization of the Ger- F. X. Brosius.3 mans had far progressed and, when that The entire episode did not augur well occurs, we may, for the purposes of this for the felicitous blending of German study, sharply curtail the treatment of and American life. -

Sister Madeleine Chaffers, SSND April 27, 1923 – August 19, 2017

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Sister Madeleine Chaffers, SSND April 27, 1923 – August 19, 2017 BALTIMORE - Sister Madeleine Chaffers, SSND, died peacefully on Aug. 19, 2017 at Villa Assumpta, Baltimore. She was 94 years old and a vowed member of the School Sisters of Notre Dame for 68 years. Sister Madeleine taught for 29 years throughout Maryland, including St. Mary High School in Annapolis, and the Institute of Notre Dame and Notre Dame Prep in Baltimore. Sister Madeleine, daughter of Dr. William and Bertha Boldue Chaffers, was born on April 27, 1923 in Lewiston, Maine. She attended public schools from kindergarten through fourth grade, and took religious instruction and French lessons from the Dominican Sisters. She received her first holy communion in the convent chapel. Madeleine completed grammar school at Saints Peter and Paul School and was confirmed at age 12 at Saints Peter and Paul Church. She attended high school at Ave Maria Academy, taught by the Dominican Sisters, in the nearby town of Sabattus. During her high school years, Madeleine began thinking of entering a teaching order of religious. Madeleine attended Rivier College in Nashua, N.H. where she studied music. After earning a degree in music, she went to Eastman School of Music at Rochester University, Rochester, N.Y. to earn a master’s degree in music. Through a friend, Madeleine found herself practicing the piano at the School Sisters of Notre Dame Convent in Rochester and became interested in the order. Sister Madeleine received the bonnet of the School Sisters of Notre Dame at St. Joseph’s Convent, Rochester and entered the candidature in Baltimore on October 15, 1947. -

Catholic High Schools Celebrate Class of 2008

Catholic high schools celebrate Class of 2008 In this special section of The Catholic Review, we salute the 2,620 graduating seniors of 21 Catholic high schools in the Archdiocese of Baltimore. Congratulations to the Class of 2008! Archbishop Curley High School, Baltimore A baccalaureate Mass was celebrated May 28 at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Baltimore. Commencement exercises were held May 30 at the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen, Homeland, for 149 graduates. Robert Jirsa, managing director for RSM McGladrey and a Curley alumnus, was the commencement speaker. Thomas Pillsbury was named Ideal Curley Man of the Year and was the valedictorian. Patrick Hairfield was the salutatorian. Graduates were offered more than $4.5 million in college scholarships. Archbishop Spalding High School, Severn A baccalaureate Mass and commencement exercises were held May 22 at the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen, Homeland, for 261 graduates. Dr. Michael E. Murphy, Archbishop Spalding president, gave the commencement address. Paul S. Inglis and Paul Devlin were recipients of the award for First in Academic Excellence, and Erin Butler was the recipient of the award for Second in Academic Excellence. Graduates were offered more than $23 million in scholarships and grants. Bishop Walsh School, Cumberland A baccalaureate Mass and commencement exercises were held May 23 at St. Patrick, Cumberland, for 52 graduates. Bishop W. Francis Malooly, western vicar, was the celebrant. Ray Miller gave the welcome address and Ann Czapski gave the farewell address. The graduates earned more than $2.5 million in scholarships. Calvert Hall College High School, Towson A baccalaureate Mass and commencement exercises were held May 31 at the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen for 260 graduates. -

Conf Card 2017-18.Pmd

2018-19 STATEMENT REGARDING THE CONFIDENTIALITY OF WRITTEN RECOMMENDATIONS FOR STUDENT APPLICANTS TO AIMS SCHOOLS ASSOCIATION OF INDEPENDENT MARYLAND & DC SCHOOLS 890 Airport Park Road, Suite 103, Glen Burnie, MD 21061 www.aimsmddc.org The AIMS member schools listed on this card represent a wide range of educational alternatives. We agree to abide by the procedures and statements expressed below: 1. The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (Buckley Amendment) does not apply to Admission Folders. 2. All information provided on the attached recommendation form will be held in strictest confidence and will not be shared with students, parents, or guardians. 3. If a student is rejected for admission, the recommendation will be destroyed. 4. If a student is admitted and if the school wishes to retain the recommendation, it will be filed separately and not added to the student's permanent record folder. over... Aidan Montessori School Grace Episcopal Day School Oldfields School Alpert Family Aleph Bet Jewish Day School Green Acres School The Park School of Baltimore Annapolis Area Christian School The GreenMount School Parkmont School Archbishop Spalding High School Greenspring Montessori School The Primary Day School Baltimore Lab School The Gunston School The River School Barnesville School of Arts & Sciences The Harbor School Rochambeau, The French International School Barrie School Harford Day School Roland Park Country School Beauvoir, The National Cathedral Elementary School Highlands School Saint Andrew's United Methodist Day School Beth Tfiloh Dahan Community School Holton-Arms School Saint James School The Boys’ Latin School of Maryland Holy Trinity Episcopal Day School Sandy Spring Friends School The Bryn Mawr School Indian Creek School Seneca Academy Bullis School Institute of Notre Dame Severn School Calvert Hall College High School Jemicy School Sheridan School Calvert School Kent School Sidwell Friends School The Calverton School The Key School St. -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1983, Volume 78, Issue No. 4

Maryland Historical Magazine Published Quarterly by The Museum and Library of Maryland History The Maryland Historical Society Winter 1983 THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS, 1983-1984 J. Fife Symington, Jr., Chairman* Robert G. Merrick, Sr., Honorary Chairman Leonard C. Crewe, Jr., Vice Chairman* Brian B. Topping, President* Mrs. Charles W. Cole, Jr., Vice President* William C. Whitridge, Vice President* E. Phillips Hathaway, Vice President* Richard P. Moran, Secretary* J. Jefferson Miller, II, Vice President* Mrs. Frederick W. Lafferty, Treasurer* Walter D. Pinkard, Sr., Vice President* Samuel Hopkins, Past President* Truman T. Semans, Vice President* Bryson L. Cook, Counsel* Frank H. Weller, Jr., Vice President* * The officers listed above constitute the Society's Executive Committee. BOARD OF TRUSTEES, 1983-1984 H. Furlong Baldwin H. Irvine Keyser, II (Honorary) Mrs. Emory J. Barber, St. Mary's Co. Richard R. Kline, Frederick Co. Gary Black, Jr. John S. Lalley John E. Boulais, Caroline Co. Calvert C. McCabe, Jr. J. Henry Butta Robert G. Merrick, Jr. Mrs. James Frederick Colwill (Honorary) Michael Middleton, Charles Co. Owen Daly, II W. Griffin Morrel Donald L. DeVries Jack Moseley Leslie B. Disharoon Thomas S. Nichols (Honorary) Deborah B. English Mrs. Brice Phillips, Worcester Co. Charles 0. Fisher, Carroll Co. J. Hurst Purnell, Jr., Kent Co. Louis L. Goldstein, Calvert Co. George M. Radcliffe Anne L. Gormer, Allegany Co. Adrian P. Reed, Queen Anne's Co. Kingdon Gould, Jr., Howard Co. Richard C. Riggs, Jr. William Grant, Garrett Co. Mrs. Timothy Rodgers Benjamin H. Griswold, III David Rogers, Wicomico Co. R. Patrick Hayman, Somerset Co. John D. Schapiro Louis G.