Small Animal Dentistry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Academic Affiliate Fellowship Practice Exam: 2019

Academic Affiliate Fellowship Practice Exam: 2019 1 American Academy of Oral Medicine Mock Academic Affiliate Fellowship Examination 2019 Current History: A patient presents to your practice complaining of a “tight” feeling in her perioral tissue area. She is unable to open her mouth fully since the tissues do not stretch. She is also wearing gloves today and the weather is quite warm outside. The dental history from records sent by her previous dental office are more than three years old and she has not been seen by a dentist or hygienist since she moved from her previous city. Medical History: The patient is 57 years old, post-menopausal, she is taking the following medications: Ranitidine 150mg for GERD, 50 mcg Synthroid, calcium 1200 mg., and muti-vitamins. She reports no prior drug 2 American Academy of Oral Medicine Mock Academic Affiliate Fellowship Examination 2019 use, tobacco use and consumes alcohol on a limited basis. Hospital history has been limited to child birth. Oral Exam: The patient reports difficulty in swallowing at times and has limited oral opening of her mouth when eating sandwiches and burgers. The lip tissue appears lighter in color and the texture is smooth but very firm and not as pliable as normal lip tissue. She has some periodontal ligament widening in selected areas and a noted loss of attached gingiva with recession. Extra Oral Exam: Her fingers appear somewhat red at the tips of fingers and cool to touch. She tells you that she wears gloves a lot even in the summer while in air conditioned rooms. -

Eruption Abnormalities in Permanent Molars: Differential Diagnosis and Radiographic Exploration

DOI: 10.1051/odfen/2014054 J Dentofacial Anom Orthod 2015;18:403 © The authors Eruption abnormalities in permanent molars: differential diagnosis and radiographic exploration J. Cohen-Lévy1, N. Cohen2 1 Dental surgeon, DFO specialist 2 Dental surgeon ABSTRACT Abnormalities of permanent molar eruption are relatively rare, and particularly difficult to deal with,. Diagnosis is founded mainly on radiographs, the systematic analysis of which is detailed here. Necessary terms such as non-eruption, impaction, embedding, primary failure of eruption and ankylosis are defined and situated in their clinical context, illustrated by typical cases. KEY WORDS Molars, impaction, primary failure of eruption (PFE), dilaceration, ankylosis INTRODUCTION Dental eruption is a complex developmen- at 0.08% for second maxillary molars and tal process during which the dental germ 0.01% for first mandibular molars. More re- moves in a coordinated fashion through cently, considerably higher prevalence rates time and space as it continues the edifica- were reported in retrospective studies based tion of the root; its 3-dimensional pathway on orthodontic consultation records: 2.3% crosses the alveolar bone up to the oral for second molar eruption abnormalities as epithelium to reach its final position in the a whole, comprising 1.5% ectopic eruption, occlusion plane. This local process is regu- 0.2% impaction and 0.6% primary failure of lated by genes expressing in the dental fol- eruption (PFE) (Bondemark and Tsiopa4), and licle, at critical periods following a precise up to 1.36% permanent second molar iim- chronology, bilaterally coordinated with fa- paction according to Cassetta et al.6. cial growth. -

Download PDF File

Folia Morphol. Vol. 76, No. 1, pp. 128–133 DOI: 10.5603/FM.a2016.0046 C A S E R E P O R T Copyright © 2017 Via Medica ISSN 0015–5659 www.fm.viamedica.pl Dens invagination and root dilaceration in double multilobed mesiodentes in 14-year-old patient with anorexia nervosa J. Bagińska1, E. Rodakowska2, Sz. Piszczatowski3, A. Kierklo1, E. Duraj4, J. Konstantynowicz5 1Department of Dentistry Propaedeutics, Medical University of Bialystok, Poland 2Department of Restorative Dentistry, Medical University of Bialystok, Poland 3Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Bialystok University of Technology, Bialystok, Poland 4Department of Periodontal and Oral Mucosa Diseases, Medical University of Bialystok, Poland 5Department of Paediatrics and Developmental Disorders, Medical University of Bialystok, Poland [Received: 16 June 2016; Accepted: 1 August 2016] This paper describes a rare case of erupted double supernumerary teeth with unusual morphology in a 14-year-old patient with an eating disorder. The coexi- stence of dental morphological anomalies: multilobed mesiodens, multiple dens in dente of different types and root dilaceration have not been previously reported. The paper highlights anatomical and radiological aspects of dental abnormalities and clinical implications of delayed treatment. (Folia Morphol 2017; 76, 1: 128–133) Key words: supernumerary teeth, mesiodens, dens in dente, root dilacerations, computed tomography INTRODUCTION The shape of rudimentary mesiodens is mostly There are several dental abnormalities, including conical (peg-shaped, canine-like). Less often the changes in the number of teeth and deformities in crown is complicated with many tubercules (tuber- crown morphology, root formation or pulp cavity culated, lobular-like) or is molariform. A multilobed composition. -

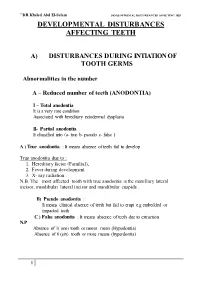

Developmental Disturbances Affecting Teeth

``DR.Khaled Abd El-Salam DEVELO PMENTAL DISTURBANCES AFFECTING TEET DEVELOPMENTAL DISTURBANCES AFFECTING TEETH A) DISTURBANCES DURING INTIATION OF TOOTH GERMS Abnormalities in the number A – Reduced number of teeth (ANODONTIA) I – Total anodontia It is a very rare condition Associated with hereditary ectodermal dysplasia II- Partial anodontia It classified into (a- true b- pseudo c- false ) A ) True anodontia : It means absence of teeth fail to develop True anodontia due to : 1. Hereditary factor (Familial), 2. Fever during development. 3. X- ray radiation . N.B. The most affected tooth with true anodontia is the maxillary lateral incisor, mandibular lateral incisor and mandibular cuspids . B) Pseudo anodontia : It means clinical absence of teeth but fail to erupt e.g embedded or impacted teeth C ) False anodontia : It means absence of teeth due to extraction N.P Absence of 1( one) tooth or mores mean (Hypodontia) Absence of 6 (six) tooth or more means (hyperdontia) 1 ``DR.Khaled Abd El-Salam DEVELO PMENTAL DISTURBANCES AFFECTING TEET ECTODERMAL DYSPLASIA • It is a hereditary disease which involves all structures which are derived from the ectoderm . • It is characterized by (general manifestation) : 1- Skin ( thin, smooth, Dry skin) 2- Hair (Absence or reduction (hypotrichosis). 3- Sweat-gland (Absence anhydrosis). 4- sebaceous gland ( absent lead to dry skin) 5-Temperature elevation (because of anhydrosis) 6- Depressed bridge of the nose 7- Defective mental development 8- Defective of finger nail Oral manifestation include teeth and -

Parameters of Care for the Specialty of Prosthodontics (2020)

SUPPLEMENT ARTICLE Parameters of Care for the Specialty of Prosthodontics doi: 10.1111/jopr.13176 PREAMBLE—Third Edition THE PARAMETERS OF CARE continue to stand the test of time and reflect the clinical practice of prosthodontics at the specialty level. The specialty is defined by these parameters, the definition approved by the American Dental Association Commission on Dental Education and Licensure (2001), the American Board of Prosthodontics Certifying Examination process and its popula- tion of diplomates, and the ADA Commission on Dental Accreditation (CODA) Standards for Advanced Education Programs in Prosthodontics. The consistency in these four defining documents represents an active philosophy of patient care, learning, and certification that represents prosthodontics. Changes that have occurred in prosthodontic practice since 2005 required an update to the Parameters of Care for the Specialty of Prosthodontics. Advances in digital technologies have led to new methods in all aspects of care. Advances in the application of dental materials to replace missing teeth and supporting tissues require broadening the scope of care regarding the materials selected for patient treatment needs. Merging traditional prosthodontics with innovation means that new materials, new technology, and new approaches must be integrated within the scope of prosthodontic care, including surgical aspects, especially regarding dental implants. This growth occurred while emphasis continued on interdisciplinary referral, collaboration, and care. The Third Edition of the Parameters of Care for the Specialty of Prosthodontics is another defining moment for prosthodontics and its contributions to clinical practice. An additional seven prosthodontic parameters have been added to reflect the changes in clinical practice and fully support the changes in accreditation standards. -

Dentofacial Trauma in Selected Contact Sports Among High School Students in Nairobi City County

DENTOFACIAL TRAUMA IN SELECTED CONTACT SPORTS AMONG HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS IN NAIROBI CITY COUNTY V60/69227/2013 THOMAS MUNYAO JUNIOR (BDS - UoN) DEPARTMENT OF PAEDIATRIC DENTISTRY & ORTHODONTICS SCHOOL OF DENTAL SCIENCES COLLEGE OF HEALTH SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF A MASTERS DEGREE IN PAEDIATRIC DENTISTRY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2016 DECLARATION I, Thomas Munyao Jr, hereby declare that this dissertation is my original work and has not been presented for the award of a degree in any other university. Signed:…………………………………………. Date: ………………………………………… DR THOMAS MUNYAO JUNIOR (BDS, NBI) ii APPROVAL This dissertation has been submitted for examination with our approval, as the University of Nairobi supervisors. SUPERVISORS: 1. DR. JAMES LWANGA NGESA, BDS (UoN), MChD (UWC). Department of Paediatric Dentistry and Orthodontics, School of Dental Sciences, University of Nairobi Signed………………………… Date ………………………. 2. DR. MARJORIE MUASYA, BDS (UON), MDS (UoN). Department of Paediatric Dentistry and Orthodontics, School of Dental Sciences, University of Nairobi Signed………………………… Date ……………………. iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my loving, supportive and caring wife, Diana Masara Kemunto and my son, Gabriel Mumina Munyao Junior. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I thank The Lord Almighty for His grace upon my life and my family for always being there for me. I would like to extend my sincere gratitude to my two supervisors; Dr. J. L. Ngesa and Dr. M. Muasya for their constant supervision, guidance, patience, time and support. In addition, I would like to thank all the other lecturers from the Department of Paediatric Dentistry and Orthodontics for their valuable contribution. -

November 2000

cda journal, vol 28, nº 11 CDA Journal Volume 28, Number 11 Journal november 2000 departments 821 The Editor/A Long Time Coming 826 Impressions/Charitable Trust an Option for Practice Transition 880 Dr. Bob/The Best Health News You’ve Heard All Year features 836 DENTAL TRAUMA: IMPROVING TREATMENT OBJECTIVES An introduction to the issue. By Anthony J. DiAngelis, DMD, MPH 838 DENTAL MANAGEMENT OF TRAUMATIC INJURIES TO THE PRIMARY DENTITION A umber of issues relative to primary dentition trauma are summarized and a system for treatment provided. By Clifton O. Dummett, Jr., DDS, MSD, MEd 846 DECORONATION: HOW, WHY, AND WHEN? A surgical method for treating ankylosed incisors in children and adolescents is provided. By Barbro Malmgren 855 MANAGEMENT OF TRAUMATICALLY INJURED PULPS IN IMMATURE TEETH USING MTA A technique for using MTA for vital pulp therapy on teeth with crown fractures is described. By Leif K. Bakland, DDS 860 LUXATION INJURIES AND EXTERNAL ROOT RESORPTIon -- ETIOLOGY, TREATMENT, AND PROGNOSIS Treatment options for root resorption resulting from luxation injuries are outlined. By Martin Trope, DMD head Editor cda journal, vol 28, n 11 º Achieving Consensus Jack F. Conley, DDS he case: The Federal Trade association for more than a decade. The “negative” changes in the profession they Commission vs. the California fact alone that the U.S. Supreme Court felt had been imposed by regulations set Dental Association regarding had accepted and agreed to hear the case forth by outside agencies such as the FTC. advertising guidelines. Many in early 1999 was considered somewhat Nonetheless, because of what had become of us who had seen the start of of a victory. -

Orthodontic Treatment of an Impacted Dilacerated Maxillary Incisor: a Case Report

Orthodontic treatment of an impacted dilacerated maxillary incisor: A case report Orthodontic treatment of an impacted dilacerated maxillary incisor: A case report Paola Cozza*/ Alessandra Marino**/ Roberta Condo*** Dilaceration is one of the causes of permanent maxillary incisor eruption failure. It is a developmen- tal distortion of the form of a tooth that commonly occurs in permanent incisors as result of trauma to the primary predecessors whose apices lie close to the permanent tooth germ. We present a case of post-traumatic impaction of a dilacerated central maxillary left incisor in a young patient with a class II malocclusion. J Clin Pediatr Dent 30(2): 93-98, 2005 INTRODUCTION adopted to save an impacted dilacerated incisor. ilaceration is one of the causes of permanent Because of the root angulation of the impacted incisor, maxillary incisor eruption failure and repre- multiple surgeries complicated orthodontic manage- sents a challenge to clinicians.1 ment, additional periodontal surgery and a comprised D 5,6 It is a developmental distortion of the form of a gingival margin usually are inevitable. tooth that commonly occurs in permanent incisors as We present a case of post-traumatic impaction of a result of trauma to the primary predecessors whose dilacerated central maxillary left incisor in a young apices lie close to the permanent tooth germ. The new patient with a class II malocclusion. portion of tooth, generally the root, is formed at an angle in relation to the crown portion formed before CASE REPORT the injury.2 The treatment of dilacerated anterior teeth poses a HISTORY AND INITIAL EXAMINATION clinical dilemma because of its difficult position. -

DLA 2220 Oral Pathology

ILLINOIS VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE COURSE OUTLINE DIVISION: Workforce Development COURSE: DLA 2220 Oral Pathology Date: Spring 2021 Credit Hours: 0.5 Prerequisite(s): DLA 1210 Dental Science II Delivery Method: Lecture 0.5 Contact Hours (1 contact = 1 credit hour) Seminar 0 Contact Hours (1 contact = 1 credit hour) Lab 0 Contact Hours (2-3 contact = 1 credit hour) Clinical 0 Contact Hours (3 contact = 1 credit hour) Online Blended Offered: Fall Spring Summer CATALOG DESCRIPTION: The field of oral pathology will be studied, familiarizing the student with oral diseases, their causes (if known), and their effects on the body. A dental assistant does not diagnose oral pathological diseases, but may alert the dentist to abnormal conditions of the mouth. This course will ensure a basic understanding of recognizing abnormal conditions (anomalies), how to prevent disease transmission, how the identified pathological condition may interfere with planned treatment, and what effect the condition will have on the overall health of the patient. Curriculum Committee – Course Outline Form Revised 12/5/2016 Page 1 of 9 GENERAL EDUCATION GOALS ADDRESSED [See last page for Course Competency/Assessment Methods Matrix.] Upon completion of the course, the student will be able: [Choose up to three goals that will be formally assessed in this course.] To apply analytical and problem solving skills to personal, social, and professional issues and situations. To communicate successfully, both orally and in writing, to a variety of audiences. To construct a critical awareness of and appreciate diversity. To understand and use technology effectively and to understand its impact on the individual and society. -

Common Icd-10 Dental Codes

COMMON ICD-10 DENTAL CODES SERVICE PROVIDERS SHOULD BE AWARE THAT AN ICD-10 CODE IS A DIAGNOSTIC CODE. i.e. A CODE GIVING THE REASON FOR A PROCEDURE; SO THERE MIGHT BE MORE THAN ONE ICD-10 CODE FOR A PARTICULAR PROCEDURE CODE AND THE SERVICE PROVIDER NEEDS TO SELECT WHICHEVER IS THE MOST APPROPRIATE. ICD10 Code ICD-10 DESCRIPTOR FROM WHO (complete) OWN REFERENCE / INTERPRETATION/ CIRCUM- STANCES IN WHICH THESE ICD-10 CODES MAY BE USED TIP:If you are viewing this electronically, in order to locate any word in the document, click CONTROL-F and type in word you are looking for. K00 Disorders of tooth development and eruption Not a valid code. Heading only. K00.0 Anodontia Congenitally missing teeth - complete or partial K00.1 Supernumerary teeth Mesiodens K00.2 Abnormalities of tooth size and form Macr/micro-dontia, dens in dente, cocrescence,fusion, gemination, peg K00.3 Mottled teeth Fluorosis K00.4 Disturbances in tooth formation Enamel hypoplasia, dilaceration, Turner K00.5 Hereditary disturbances in tooth structure, not elsewhere classified Amylo/dentino-genisis imperfecta K00.6 Disturbances in tooth eruption Natal/neonatal teeth, retained deciduous tooth, premature, late K00.7 Teething syndrome Teething K00.8 Other disorders of tooth development Colour changes due to blood incompatability, biliary, porphyria, tetyracycline K00.9 Disorders of tooth development, unspecified K01 Embedded and impacted teeth Not a valid code. Heading only. K01.0 Embedded teeth Distinguish from impacted tooth K01.1 Impacted teeth Impacted tooth (in contact with another tooth) K02 Dental caries Not a valid code. Heading only. -

Dental Anomalies 4

學習目標 牙體形態學Dental morphology w能辨識及敘述牙齒之形態、特徵與功能意義,並能應用於臨床診斷與治療 1. 牙齒形態相關名辭術語之定義與敘述 2. 牙齒號碼系統之介紹 3. 牙齒之顎間關係與生理功能形態之考慮 Dental anomalies 4. 恒齒形態之辨識與差異之比較 5. 乳齒形態之辨識與差異之比較 6. 恒齒與乳齒之比較 7. 牙髓腔形態 臺北醫學大學 牙醫學系 8. 牙齒之萌出、排列與咬合 董德瑞老師 9. 牙體形態學與各牙科臨床科目之相關 10. 牙科人類學與演化發育之探討 [email protected] 參考資料 Summary I. Anodontia: absence of teeth 1. Woelfel, J.B. and Scheid, R.C: Dental Anatomy--Its Relevance to Dentistry, ed. 6, A. Total anodontia Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2002. B. Partial anodontia 2. Jordan, R.E. and Abrams, L.: Kraus' Dental Anatomy and Occlusion, ed. 2, Mosby II. Extra or supernumerary teeth Year Book, St. Louis,1992. 3. Ash, M.M.and Nelson, S.J.: Wheeler's Dental Anatomy, Physiology and Occlusion, A. Maxillary incisor area ed. 8, W.B. Saunders Co., 2003. B. Third molar area C. Mandibular premolar area III. Abnormal tooth morphology A. Abnormal crown morphology B. Abnormal root morphology C. Anomalies in tooth position D. Additional tooth developmental malformations (and discoloration) E. Reactions to injury after tooth eruption F. Unusual dentitions OBJECTIVES This chapter is designed to help the learner perform the following: ~ Dental anomalies are abnormalities of teeth that range from such "common" ~ Identify variations from the normal (anomalies) for the number of teeth in an occurrences as malformed permanent maxillary lateral incisors that are peg arch. shaped to such rare occurrences as complete anodontia (no teeth at all). Dental ~ Identify anomalies in crown morphology and, when applicable, identify the anomalies are most often caused by hereditary factors (gene related) or by anomaly by name and give a possible cause (etiology). developmental or metabolic disturbances. While more anomalies occur in the permanent than primary dentition and in the maxilla than the mandible, it is ~ Identify anomalies in root morphology and, when applicable, identify the important to remember that their occurrence is rare. -

Contents Focus on Dentistry September 18-20, 2011 Albuquerque, New Mexico

Contents Focus on Dentistry September 18-20, 2011 Albuquerque, New Mexico Thanks to sponsors Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, Equine Specialties, Pfizer Animal Health, and Capps Manufacturing, Inc. for supporting the 2011 Focus on Dentistry Meeting. Sunday, September 18 Peridental Anatomy: Sinuses and Mastication Muscles ............................................... 1 Victor S. Cox, DVM, PhD Dental Anatomy .................................................................................................................8 P. M. Dixon, MVB, PhD, MRCVS Equine Periodontal Anatomy..........................................................................................25 Carsten Staszyk, Apl. Prof., Dr. med. vet. Oral and Dental Examination .........................................................................................28 Jack Easley, DVM, MS, Diplomate ABVP (Equine) How to Document a Dental Examination and Procedure Using a Dental Chart .......35 Stephen S. Galloway, DVM, FAVD Equine Dental Radiography............................................................................................50 Robert M. Baratt, DVM, MS, FAVD Beyond Radiographs: Advanced Imaging of Equine Dental Pathology .....................70 Jennifer E. Rawlinson, DVM, Diplomate American Veterinary Dental College Addressing Pain: Regional Nerve Blocks ......................................................................74 Jennifer E. Rawlinson, DVM, Diplomate American Veterinary Dental College Infraorbital Nerve Block Within the Pterygopalatine Fossa - EFBI-Technique