Goal Motives, Well-Being, and Physical Health: an Integrative Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

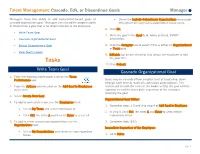

Manager Cascade, Edit, Or Discontinue Goal(S) in Workday

Talent Management: Cascade, Edit, or Discontinue Goals Manager Managers have the ability to add department-based goals or • Check the Include Subordinate Organizations to cascade cascade organization goal. Managers can also edit in-progress goals throughout all supervisory organization below yours. or discontinue a goal that is no longer relevant to the employee. 6. Click OK. • Write Team Goal 7. Write the goal in the Goal field. Add a detailed, SMART • Cascade Organizational Goal description. • Edit or Discontinue a Goal 8. Click the Category box to select if this is either an Organizational or Team goal. • View Team’s Goals 9. Editable will be pre-selected. This allows the employee to edit Tasks the goal title. 10. Click Submit. Write Team Goal Cascade Organizational Goal 1. From the Workday home page, click on the Team Performance app. Goals may be cascaded from a higher level of leadership, down through each level to reach all supervisory organizations. This 2. From the Actions column, click on the Add Goal to Employees section will include the steps of the leader writing the goal and the menu item. approval step of the immediate supervisor of the employee receiving the goal. 3. Select Create New Goal. Organizational Goal Writer: 4. To add to immediate team, use the Employees field: 1. Complete steps 1-3 and skip step 4 of Add Goal to Employee. • Select My Team and select individuals or 2. In step 5, click Ctrl, the letter A and Enter to select entire • Click Ctrl, the letter A and then hit Enter to select all. -

Personal Goals, Life Meaning, and Virtue: Wellsprings of a Positive Life

5 PERSONAL GOALS, LIFE MEANING, AND VIRTUE: WELLSPRINGS OF A POSITIVE LIFE ROBERT A. EMMONS Nothing is so insufferable to man as to be completely at rest, without passions, without business, without diversion, without effort. Then he feels his nothingness, his forlornness, his insufficiency, his weakness, his emptiness. (Pascal, The Pensees, 1660/1950, p. 57). As far as we know humans are the only meaning-seeking species on the planet. Meaning-making is an activity that is distinctly human, a function of how the human brain is organized. The many ways in which humans conceptualize, create, and search for meaning has become a recent focus of behavioral science research on quality of life and subjective well-being. This chapter will review the recent literature on meaning-making in the context of personal goals and life purpose. My intention will be to document how meaningful living, expressed as the pursuit of personally significant goals, contributes to positive experience and to a positive life. THE CENTRALITY OF GOALS IN HUMAN FUNCTIONING Since the mid-1980s, considerable progress has been made in under- standing how goals contribute to long-term levels of well-being. Goals have been identified as key integrative and analytic units in the study of human Preparation of this chapter was supported by a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. I would like to express my gratitude to Corey Lee Keyes and Jon Haidt for the helpful comments on an earlier draft of this chapter. 105 motivation (see Austin & Vancouver, 1996; Karoly, 1999, for reviews). The driving concern has been to understand how personal goals are related to long-term levels of happiness and life satisfaction and how ultimately to use this knowledge in a way that might optimize human well- being. -

Management by Objectives: Advantages, Problems, Implications for Community Colleges

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 057 792 JC 720 028 AUTHOR Collins, Robert W. TITLE Management by Objectives: Advantages, Problems, Implications for Community Colleges. PUB DATE 71 NOTE 20p.; Seminar paper EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS Administrative Principles; Decision Making; *Educational Administration; *Junior Colleges; *Management; *Management Development; *Management Systems; Objectives ABSTRACT Not new in principle, management by objectives (MBO) focuses on the goals of an institution stated as end accomplishments. Community college administrators have been attracted by the reputed benefits of MBO: increased productivity, improved planning, maximized profits, objective managerial evaluation, and improved participant morale. This paper summarizes the advantages and disadvantages of MBO learned and reported from business and industry. Problems encountered in MBO programs include: lack of total organizational commitment, lack of prerequisites to implementation, failpre to integrate individual and organizational goals, overemph sis on measurable goal attainment, and inadequacies in performance a praisal. To be most effective in community colleges, MBO must have the total backing of board members and the president. Furthermore, the school must be prepared to commit extra time to implement MBO. The major determinant of the success or failure of MBO type programs is largely a result of its acceptance by users. (IA1 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH. EDUCATION & WELFARE Of'FICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO- DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIG- INATING IT POINTS 0:' VIEW OR OPIN- IONS STATED DC NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL. -FFICE OF EDU- "CATION.POSITION OR POLICY. CNJ MANAGEMENT BY OBJECTIVES: ADVANTAGES, PROBLEMS, IMPLICATIONS FOR COMMUNITY COLLEGES BY: Robert W. -

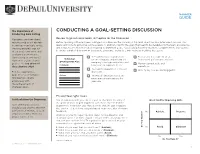

CONDUCTING a GOAL-SETTING DISCUSSION Conducting Goal Setting

MANAGER GUIDE The Importance of CONDUCTING A GOAL-SETTING DISCUSSION Conducting Goal Setting Managers and their direct Review Organizational Goals to Prepare for the Discussion reports need to collaborate Before speaking with employees, managers should review the company’s top-level objectives and determine how your own in setting meaningful goals, goals contribute to achieving business goals. In addition, identify the goals that need to be delegated to the team, and provide tracking progress against direct reports with the information required to draft their goals. You should advise the reports to complete the following steps those goals over time, and to create a draft of their performance goals, strategies, and tactics before the goal-setting discussion: evaluating performance. Connecting an employee’s Re-read the mission and vision Review any development areas Individual work with organizational for the company; understand the from recent performance reviews. Development Plan company’s strategic objectives and goals is the top driver of Review current goals and Comments how your job supports them. discretionary effort. aspirations. Re-read the department’s mission Identify any new overarching goals. For the organization, and vision. goal-driven performance Actions Review job description and any management aligns performance expectations for employees with your role. the achievement of strategic goals. Ensure Meaningful Goals Set Goals from the Beginning You should work with your direct report to check the accuracy of Goals Grid for Improving Skills the goals and assess goal alignment with those of peers and the Goal-setting discussions department. In addition, you should ensure that the goals support should occur shortly after the the employees’ development goals based on any recent performance performance reviews or as an feedback. -

Goal Setting Workbook

Workbook for Goal-setting and Evidence-based Strategies for Success Complete Workbook by Caroline Adams Miller, MAPP Author of Creating Your Best Life: The Ultimate Life List Guide Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 Theme One: Flourishing ................................................................................................. 6 Why Does Flourishing Matter? ................................................................................... 6 Success Flows from Happiness ................................................................................ 6 The Positivity Ratio .................................................................................................. 7 From the Source: Martin Seligman on Flourishing ................................................... 8 Jolts of Joy ................................................................................................................... 9 Happiness Boosters Worksheet ..............................................................................11 Introducing Character Strengths .............................................................................. 12 Exploring Your Own Character Strengths ............................................................. 13 Looking Back: Me at My Best ................................................................................ 14 Find Your Person-Activity Fit .................................................................................. -

Effect of Goal Setting for Motivation, Self-Efficacy, and Performance in Elementary Mathematics

International Journal of Instruction October 2020 ● Vol.13, No.4 e-ISSN: 1308-1470 ● www.e-iji.net p-ISSN: 1694-609X pp. 1-16 Received: 21/08/2019 Revision: 15/03/2020 Accepted: 01/04/2020 OnlineFirst:02/07/2020 Effect of Goal Setting for Motivation, Self-Efficacy, and Performance in Elementary Mathematics Jacklyne D. Sides University of North Georgia, USA, [email protected] Joshua A. Cuevas Assoc. Prof., University of North Georgia, USA, [email protected] Goal setting is utilized by adults regularly to foster success. It has also been shown to benefit academic achievement. This 8-week study sought to determine the effects of goal setting on motivation, self-efficacy, and math achievement in elementary students. The quasi-experimental study included 70 students in 3rd and 4th grade math classes. Students in the experimental group were involved in setting an achievement goal for fluency of multiplication facts. The students monitored their progress through a weekly graphing and reflection activity. The results indicated that elementary students involved in setting goals showed an increase in their mathematical performance of multiplication facts. However, based on the results from this study, goal setting did not have an impact on motivation or self- efficacy. These results support the concept of goal setting theory in the academic setting, suggesting that it may be beneficial for teachers to include goal setting in their day-to-day instructional practices, though further research on its effect on affective traits is warranted. Keywords: goal setting, motivation, self-efficacy, elementary, mathematics, goal setting theory INTRODUCTION There is ongoing research to determine the best methods for how to assist students in achieving academic success. -

Understanding the Mental Status Examination with the Help of Videos

Understanding the Mental Status Examination with the help of videos Dr. Anvesh Roy Psychiatry Resident, University of Toronto Introduction • The mental status examination describes the sum total of the examiner’s observations and impressions of the psychiatric patient at the time of the interview. • Whereas the patient's history remains stable, the patient's mental status can change from day to day or hour to hour. • Even when a patient is mute, is incoherent, or refuses to answer questions, the clinician can obtain a wealth of information through careful observation. Outline for the Mental Status Examination • Appearance • Overt behavior • Attitude • Speech • Mood and affect • Thinking – a. Form – b. Content • Perceptions • Sensorium – a. Alertness – b. Orientation (person, place, time) – c. Concentration – d. Memory (immediate, recent, long term) – e. Calculations – f. Fund of knowledge – g. Abstract reasoning • Insight • Judgment Appearance • Examples of items in the appearance category include body type, posture, poise, clothes, grooming, hair, and nails. • Common terms used to describe appearance are healthy, sickly, ill at ease, looks older/younger than stated age, disheveled, childlike, and bizarre. • Signs of anxiety are noted: moist hands, perspiring forehead, tense posture and wide eyes. Appearance Example (from Psychosis video) • The pt. is a 23 y.o male who appears his age. There is poor grooming and personal hygiene evidenced by foul body odor and long unkempt hair. The pt. is wearing a worn T-Shirt with an odd symbol looking like a shield. This appears to be related to his delusions that he needs ‘antivirus’ protection from people who can access his mind. -

Our Mission, Vision, Strategic Goals, and Objectives

OUR MISSION,VISION, STRATEGIC GOALS, AND OBJECTIVES 1 STRATEGIC GOAL 2 FY 2004 - FY 2009 STRATEGIC PLAN OUR MISSION, VISION, STRATEGIC GOALS, AND OBJECTIVES Our Mission,Vision, Strategic Goals, and Objectives Mission Statement The Department of Commerce creates the conditions for economic growth and opportunity by promoting innovation, entrepreneurship, competitiveness, and stewardship. Vision or almost 100 years, the Department of Commerce has partnered with U.S. businesses to maintain a prosperous, productive America that is committed to consumer safety and the protection of natural resources. Together, we have a Frecord of innovation in manufacturing, transportation, communications, measurement, and materials that has helped to sustain U.S. leadership of the international marketplace. By assisting the private sector, our vision is that the United States continues to play a lead role in the world economy. Strategic Goals To achieve this mission and fulfill our vision, we have three strategic goals and a management integration goal. Each strategic goal involves activities that touch American lives every day. GOAL 1: Provide the information and tools to maximize U.S. competitiveness and enable economic growth for American industries, workers, and consumers General Goal/Objective 1.1: Enhance economic growth for all Americans by developing partnerships with private sector and nongovernmental organizations. General Goal/Objective 1.2: Advance responsible economic growth and trade while protecting American security. General Goal/Objective 1.3: Enhance the supply of key economic and demographic data to support effective decision-making of policymakers, businesses, and the American public. Activities Collect, analyze, and disseminate demographic and economic data to serve public and private decisionmakers at all levels, on fiscal and monetary policy, business finance and investment strategy, and personal household economic matters. -

06. Servant Leadership & Path-Goal Theory

IMSA Leadership Education and Development "Everybody can be great because everybody can serve. You don’t have to have a college degree to serve. You don’t have to make your subject and your verb agree to serve…You only need a heart full of grace, a soul generated by love." - Martin Luther King Jr. Time Period and Situation The term “servant leader” was first documented by Robert K. Greenleaf in 1970, who credits the formulation of the term to the 1956 novel The Journey to the East (Northouse 226). Right at the tail end of WWII, the 1950s made way for the Civil Rights Movement. For context, this time period brought about the invention of TV and widespread use of cars in America, the Korean War, and the Cold War. Throughout the Civil Rights Movement, Martin Luther King’s success as one major face of the movement became accredited to his devotion to servant leadership that became a highlight of the era. Path Goal Theory first emerged in leadership texts in the early 1970s (Northouse 115). Leading up to this point, the Civil Rights movement still had a heavy presence in society, and technological advancements landed the first man on the moon (“1960s”). Agenda 1. Theories a. Servant Leadership b. Path Goal Theory 2. Servant Leadership Examples a. Jesus Christ b. Albert Schweitzer 3. Path Goal Leadership Examples a. Columbia Records b. Steve Jobs Student Objectives: 1. Students will understand the definition of servant leadership 2. Students will understand the definition of path-goal theory Revised July 2018 IMSA Leadership Education and Development Theories 1. -

Strategic Planning Basics for Managers

STRATEGIC PLANNING Guide for Managers 1 Strategic Planning Basics for Managers In all UN offices, departments and missions, it is critical that managers utilize the most effective approach toward developing a strategy for their existing programmes and when creating new programmes. Managers use the strategy to communicate the direction to staff members and guide the larger department or office work. Here you will find practical techniques based on global management best practices. Strategic planning defined Strategic planning is a process of looking into the future and identifying trends and issues against which to align organizational priorities of the Department or Office. Within the Departments and Offices, it means aligning a division, section, unit or team to a higher-level strategy. In the UN, strategy is often about achieving a goal in the most effective and efficient manner possible. For a few UN offices (and many organizations outside the UN), strategy is about achieving a mission comparatively better than another organization (i.e. competition). For everyone, strategic planning is about understanding the challenges, trends and issues; understanding who are the key beneficiaries or clients and what they need; and determining the most effective and efficient way possible to achieve the mandate. A good strategy drives focus, accountability, and results. How and where to apply strategic planning UN departments, offices, missions and programmes develop strategic plans to guide the delivery of an overall mandate and direct multiple streams of work. Sub-entities create compatible strategies depending on their size and operational focus. Smaller teams within a department/office or mission may not need to create strategies; there are, however, situations in which small and medium teams may need to think strategically, in which case the following best practices can help structure the thinking. -

Self-Criticism and Goal Progress

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 26, No. 7, 2007, pp. 826-840 SELF-CRITICISM, GOAL MOTIVATION, AND GOAL PROGRESS THEODORE A. POWERS University of Massactiusetts Dartmouth RICHARD KOESTNER AND DAVID C. ZUROFF McGill University The current research examined the relations among self-criticism, autonomous versus controlled motivations, and goal progress. Recent researchers have sug- gested that self-critics are less autonomously motivated, that is, that their goals are less tied to their interests and personal meaning than is true for other individuals, and that the effects of self-criticism on goal progress are mediated by lower levels of autonomous motivation. The results of two short-term, prospective studies con- ducted in the United States and Canada indicated that self-criticism was negatively associated with goal progress, while autonomous motivation was positively associ- ated with goal progress in one study and marginally associated in the other. The re- sults demonstrated an association between self-criticism and controlled motivation but not autonomous motivation, and they suggest that self-criticism and autonomy act independently on goal progress. In addition, the results indi- cated an association between self-criticism and rumination and procrastination that appears to mediate the impact of self-criticism on goal progress. These results highlight the need for consideration of both personality and motivational influences in the study of goal pursuits. To understand the pursuit of personal goals one must consider the im- portance of both personality and motivational factors, the who and the why. Personahty theories and recent empirical findings support the idea that characteristics such as self-criticism may have an impact on how and why people pursue their goals and on their success at accom- Please send correspondence to Theodore A. -

When and Why Does Belief in a Controlling God Strengthen Goal T Commitment? ⁎ Mark J

Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 75 (2018) 71–82 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Experimental Social Psychology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jesp When and why does belief in a controlling God strengthen goal T commitment? ⁎ Mark J. Landaua, , Jamel Khenferb,e, Lucas A. Keeferc, Trevor J. Swansona, Aaron C. Kayd a University of Kansas, USA b Zayed University, College of Business, P.O. Box: 144534, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates c University of Southern Mississippi, USA d Duke University, USA e Aix-Marseille University, CERGAM research center, Aix-Marseille Graduate School of Management-IAE, Chemin de la Quille, Aix-en-Provence 13540, France ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: The perception that God controls one's life can bolster motivation to pursue personal goals, but it can also have Religion no impact and even squelch motivation. To better understand how religious beliefs impact self-regulation, the Self-regulation current research built on Compensatory Control Theory's claim that perceiving the environment as predictable Control (vs. unpredictable) strengthens commitment to long-term goals. Perceiving God's intervention as following an Goals understandable logic, which implies a predictable environment, increased self-reported and behavioral com- God mitment to save money (Studies 1–3), excel academically (Study 4), and improve physical health (Study 5). In Predictability contrast, perceiving God as intervening in mysterious ways, which implies that worldly affairs are under control yet unpredictable, did not increase goal commitment. Exploratory mediational analyses focused on self-efficacy, response efficacy, and confidence in God's control. A meta-analysis (Study 6) yielded a reliable effect whereby belief in divine control supports goal pursuit specifically when it signals the predictability of one's environment.