Time, Pleasure, and Knowledge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coordinates and Proper Time

Coordinates and Proper Time Edmund Bertschinger, [email protected] January 31, 2003 Now it came to me: . the independence of the gravitational acceleration from the na- ture of the falling substance, may be expressed as follows: In a gravitational ¯eld (of small spatial extension) things behave as they do in a space free of gravitation. This happened in 1908. Why were another seven years required for the construction of the general theory of relativity? The main reason lies in the fact that it is not so easy to free oneself from the idea that coordinates must have an immediate metrical meaning. | A. Einstein (quoted in Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist, ed. P.A. Schilpp, 1949). 1. Introduction These notes supplement Chapter 1 of EBH (Exploring Black Holes by Taylor and Wheeler). They elaborate on the discussion of bookkeeper coordinates and how coordinates are related to actual physical distances and times. Also, a brief discussion of the classic Twin Paradox of special relativity is presented in order to illustrate the principal of maximal (or extremal) aging. Before going to details, let us review some jargon whose precise meaning will be important in what follows. You should be familiar with these words and their meaning. Spacetime is the four- dimensional playing ¯eld for motion. An event is a point in spacetime that is uniquely speci¯ed by giving its four coordinates (e.g. t; x; y; z). Sometimes we will ignore two of the spatial dimensions, reducing spacetime to two dimensions that can be graphed on a sheet of paper, resulting in a Minkowski diagram. -

The Book of Common Prayer

The Book of Common Prayer and Administration of the Sacraments and Other Rites and Ceremonies of the Church Together with The Psalter or Psalms of David According to the use of The Episcopal Church Church Publishing Incorporated, New York Certificate I certify that this edition of The Book of Common Prayer has been compared with a certified copy of the Standard Book, as the Canon directs, and that it conforms thereto. Gregory Michael Howe Custodian of the Standard Book of Common Prayer January, 2007 Table of Contents The Ratification of the Book of Common Prayer 8 The Preface 9 Concerning the Service of the Church 13 The Calendar of the Church Year 15 The Daily Office Daily Morning Prayer: Rite One 37 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite One 61 Daily Morning Prayer: Rite Two 75 Noonday Prayer 103 Order of Worship for the Evening 108 Daily Evening Prayer: Rite Two 115 Compline 127 Daily Devotions for Individuals and Families 137 Table of Suggested Canticles 144 The Great Litany 148 The Collects: Traditional Seasons of the Year 159 Holy Days 185 Common of Saints 195 Various Occasions 199 The Collects: Contemporary Seasons of the Year 211 Holy Days 237 Common of Saints 246 Various Occasions 251 Proper Liturgies for Special Days Ash Wednesday 264 Palm Sunday 270 Maundy Thursday 274 Good Friday 276 Holy Saturday 283 The Great Vigil of Easter 285 Holy Baptism 299 The Holy Eucharist An Exhortation 316 A Penitential Order: Rite One 319 The Holy Eucharist: Rite One 323 A Penitential Order: Rite Two 351 The Holy Eucharist: Rite Two 355 Prayers of the People -

Lecture Notes 17: Proper Time, Proper Velocity, the Energy-Momentum 4-Vector, Relativistic Kinematics, Elastic/Inelastic

UIUC Physics 436 EM Fields & Sources II Fall Semester, 2015 Lect. Notes 17 Prof. Steven Errede LECTURE NOTES 17 Proper Time and Proper Velocity As you progress along your world line {moving with “ordinary” velocity u in lab frame IRF(S)} on the ct vs. x Minkowski/space-time diagram, your watch runs slow {in your rest frame IRF(S')} in comparison to clocks on the wall in the lab frame IRF(S). The clocks on the wall in the lab frame IRF(S) tick off a time interval dt, whereas in your 2 rest frame IRF( S ) the time interval is: dt dtuu1 dt n.b. this is the exact same time dilation formula that we obtained earlier, with: 2 2 uu11uc 11 and: u uc We use uurelative speed of an object as observed in an inertial reference frame {here, u = speed of you, as observed in the lab IRF(S)}. We will henceforth use vvrelative speed between two inertial systems – e.g. IRF( S ) relative to IRF(S): Because the time interval dt occurs in your rest frame IRF( S ), we give it a special name: ddt = proper time interval (in your rest frame), and: t = proper time (in your rest frame). The name “proper” is due to a mis-translation of the French word “propre”, meaning “own”. Proper time is different than “ordinary” time, t. Proper time is a Lorentz-invariant quantity, whereas “ordinary” time t depends on the choice of IRF - i.e. “ordinary” time is not a Lorentz-invariant quantity. 222222 The Lorentz-invariant interval: dI dx dx dx dx ds c dt dx dy dz Proper time interval: d dI c2222222 ds c dt dx dy dz cdtdt22 = 0 in rest frame IRF(S) 22t Proper time: ddtttt 21 t 21 11 Because d and are Lorentz-invariant quantities: dd and: {i.e. -

Class 3: Time Dilation, Lorentz Contraction, Relativistic Velocity Transformations

Class 3: Time dilation, Lorentz contraction, relativistic velocity transformations Transformation of time intervals Suppose two events are recorded in a laboratory (frame S), e.g. by a cosmic ray detector. Event A is recorded at location xa and time ta, and event B is recorded at location xb and time tb. We want to know the time interval between these events in an inertial frame, S ′, moving with relative to the laboratory at speed u. Using the Lorentz transform, ux x′=−γ() xut,,, yyzzt ′′′ = = =− γ t , (3.1) c2 we see, from the last equation, that the time interval in S ′ is u ttba′−= ′ γ() tt ba −− γ () xx ba − , (3.2) c2 i.e., the time interval in S ′ depends not only on the time interval in the laboratory but also in the separation. If the two events are at the same location in S, the time interval (tb− t a ) measured by a clock located at the events is called the proper time interval . We also see that, because γ >1 for all frames moving relative to S, the proper time interval is the shortest time interval that can be measured between the two events. The events in the laboratory frame are not simultaneous. Is there a frame, S ″ in which the separated events are simultaneous? Since tb′′− t a′′ must be zero, we see that velocity of S ″ relative to S must be such that u c( tb− t a ) β = = , (3.3) c xb− x a i.e., the speed of S ″ relative to S is the fraction of the speed of light equal to the time interval between the events divided by the light travel time between the events. -

Debasishdas SUNDIALS to TELL the TIMES of PRAYERS in the MOSQUES of INDIA January 1, 2018 About

Authior : DebasishDas SUNDIALS TO TELL THE TIMES OF PRAYERS IN THE MOSQUES OF INDIA January 1, 2018 About It is said that Delhi has almost 1400 historical monuments.. scattered remnants of layers of history, some refer it as a city of 7 cities, some 11 cities, some even more. So, even one is to explore one monument every single day, it will take almost 4 years to cover them. Narratives on Delhi’s historical monuments are aplenty: from amateur writers penning down their experiences, to experts and archaeologists deliberating on historic structures. Similarly, such books in the English language have started appearing from as early as the late 18th century by the British that were the earliest translation of Persian texts. Period wise, we have books on all of Delhi’s seven cities (some say the city has 15 or more such cities buried in its bosom) between their covers, some focus on one of the cities, some are coffee-table books, some attempt to create easy-to-follow guide-books for the monuments, etc. While going through the vast collection of these valuable works, I found the need to tell the city’s forgotten stories, and weave them around the lesser-known monuments and structures lying scattered around the city. After all, Delhi is not a mere necropolis, as may be perceived by the un-initiated. Each of these broken and dilapidated monuments speak of untold stories, and without that context, they can hardly make a connection, however beautifully their architectural style and building plan is explained. My blog is, therefore, to combine actual on-site inspection of these sites, with interesting and insightful anecdotes of the historical personalities involved, and prepare essays with photographs and words that will attempt to offer a fresh angle to look at the city’s history. -

Minkowski's Proper Time and the Status of the Clock Hypothesis

Minkowski’s Proper Time and the Status of the Clock Hypothesis1 1 I am grateful to Stephen Lyle, Vesselin Petkov, and Graham Nerlich for their comments on the penultimate draft; any remaining infelicities or confusions are mine alone. Minkowski’s Proper Time and the Clock Hypothesis Discussion of Hermann Minkowski’s mathematical reformulation of Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity as a four-dimensional theory usually centres on the ontology of spacetime as a whole, on whether his hypothesis of the absolute world is an original contribution showing that spacetime is the fundamental entity, or whether his whole reformulation is a mere mathematical compendium loquendi. I shall not be adding to that debate here. Instead what I wish to contend is that Minkowski’s most profound and original contribution in his classic paper of 100 years ago lies in his introduction or discovery of the notion of proper time.2 This, I argue, is a physical quantity that neither Einstein nor anyone else before him had anticipated, and whose significance and novelty, extending beyond the confines of the special theory, has become appreciated only gradually and incompletely. A sign of this is the persistence of several confusions surrounding the concept, especially in matters relating to acceleration. In this paper I attempt to untangle these confusions and clarify the importance of Minkowski’s profound contribution to the ontology of modern physics. I shall be looking at three such matters in this paper: 1. The conflation of proper time with the time co-ordinate as measured in a system’s own rest frame (proper frame), and the analogy with proper length. -

Electro-Gravity Via Geometric Chronon Field

Physical Science International Journal 7(3): 152-185, 2015, Article no.PSIJ.2015.066 ISSN: 2348-0130 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Electro-Gravity via Geometric Chronon Field Eytan H. Suchard1* 1Geometry and Algorithms, Applied Neural Biometrics, Israel. Author’s contribution The sole author designed, analyzed and interpreted and prepared the manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/PSIJ/2015/18291 Editor(s): (1) Shi-Hai Dong, Department of Physics School of Physics and Mathematics National Polytechnic Institute, Mexico. (2) David F. Mota, Institute of Theoretical Astrophysics, University of Oslo, Norway. Reviewers: (1) Auffray Jean-Paul, New York University, New York, USA. (2) Anonymous, Sãopaulo State University, Brazil. (3) Anonymous, Neijiang Normal University, China. (4) Anonymous, Italy. (5) Anonymous, Hebei University, China. Complete Peer review History: http://sciencedomain.org/review-history/9858 Received 13th April 2015 th Original Research Article Accepted 9 June 2015 Published 19th June 2015 ABSTRACT Aim: To develop a model of matter that will account for electro-gravity. Interacting particles with non-gravitational fields can be seen as clocks whose trajectory is not Minkowsky geodesic. A field, in which each such small enough clock is not geodesic, can be described by a scalar field of time, whose gradient has non-zero curvature. This way the scalar field adds information to space-time, which is not anticipated by the metric tensor alone. The scalar field can’t be realized as a coordinate because it can be measured from a reference sub-manifold along different curves. In a “Big Bang” manifold, the field is simply an upper limit on measurable time by interacting clocks, backwards from each event to the big bang singularity as a limit only. -

Time in the Theory of Relativity: on Natural Clocks, Proper Time, the Clock Hypothesis, and All That

Time in the theory of relativity: on natural clocks, proper time, the clock hypothesis, and all that Mario Bacelar Valente Abstract When addressing the notion of proper time in the theory of relativity, it is usually taken for granted that the time read by an accelerated clock is given by the Minkowski proper time. However, there are authors like Harvey Brown that consider necessary an extra assumption to arrive at this result, the so-called clock hypothesis. In opposition to Brown, Richard TW Arthur takes the clock hypothesis to be already implicit in the theory. In this paper I will present a view different from these authors by taking into account Einstein’s notion of natural clock and showing its relevance to the debate. 1 Introduction: the notion of natural clock th Up until the mid 20 century the metrological definition of second was made in terms of astronomical motions. First in terms of the Earth’s rotation taken to be uniform (Barbour 2009, 2-3), i.e. the sidereal time; then in terms of the so-called ephemeris time, in which time was calculated, using Newton’s theory, from the motion of the Moon (Jespersen and Fitz-Randolph 1999, 104-6). The measurements of temporal durations relied on direct astronomical observation or on instruments (clocks) calibrated to the motions in the ‘heavens’. However soon after the adoption of a definition of second based on the ephemeris time, the improvements on atomic frequency standards led to a new definition of the second in terms of the resonance frequency of the cesium atom. -

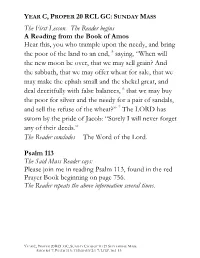

YEAR C, PROPER 20 RCL GC: S the First Lesson. the Reader Begins A

YEAR C, PROPER 20 RCL GC: SUNDAY MASS The First Lesson. The Reader begins A Reading from the Book of Amos Hear this, you who trample upon the needy, and bring the poor of the land to an end, 5 saying, “When will the new moon be over, that we may sell grain? And the sabbath, that we may offer wheat for sale, that we may make the ephah small and the shekel great, and deal deceitfully with false balances, 6 that we may buy the poor for silver and the needy for a pair of sandals, and sell the refuse of the wheat?” 7 The LORD has sworn by the pride of Jacob: “Surely I will never forget any of their deeds.” The Reader concludes The Word of the Lord. Psalm 113 The Said Mass Reader says: Please join me in reading Psalm 113, found in the red Prayer Book beginning on page 756. The Reader repeats the above information several times. YEAR C, PROPER 20 RCL GC, SUNDAY CLOSEST TO 21 SEPTEMBER : MASS : AMOS 8:4-7; PSALM 113; 1 TIMOTHY 2:1-7; LUKE 16:1-13 YEAR C, PROPER 20 RCL GC: SUNDAY MASS 1 Hallelujah! Give praise, you servants of the LORD; * praise the Name of the LORD. 2 Let the Name of the LORD be blessed, * from this time forth for evermore. 3 From the rising of the sun to its going down * let the Name of the LORD be praised. 4 The LORD is high above all nations, * and his glory above the heavens. -

Time and the Higgs (With Apologies to JB Priestley)

A quantisation of time J C Jackson 16 The Park, Newark, Nottinghamshire, UK Received 5 July 1977 Abstract. A model of discrete space-time is presented which is, in a sense, both Lorentz invariant and has no restriction on the relative velocity between particles (except v<c). The space-time has an inbuilt indeterminacy. 1. Introduction Through out the development of man’s ideas about the physical world, the view that time and space are continuous has generally prevailed. Discrete models have occasionally been entertained, with space-time events labelled by integral coordinates (Schild 1948), but these have had virtually no impact on physics. The continuous picture certainly provides an accurate description of affairs on the macroscopic scale, but there are strong advocates (notably Chew 1963; Penrose 1967) of the view that this picture must become inaccurate at the sub-microscopic level, probably when we are dealing with intervals shorter than those encountered in elementary particle physics. As a simple model of discrete space-time, Schild (1948) has considered a hyper- cubic lattice, comprising all events in Minkowski space-time whose four coordinates (t, x, y, z) are integers. The problem is that this is not a Lorentz invariant picture, as arXiv:1208.5390v1 [math-ph] 10 Aug 2012 a general Lorentz transformation destroys the hypercubicity. Schild preserves Lorentz invariance by allowing only those transformations which preserve the integer labelling. Unfortunately the smallest non-zero velocity allowed by the resulting group is 31/2c/2 where c is the velocity of light, which is not very promising as far as physical applications are concerned. -

A Biography of the Second

A BIOGRAPHY OF THE SECOND By Jessica Hendrickson B.A. Natural Sciences Hampshire College, 2006 SUBMITTED TO THE PROGRAM IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES/WRITING IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN SCIENCE WRITING AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SEPTEMBER 2020 © 2020 Jessica Hendrickson. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created Signature of Author: ____________________________________________________________ Jessica Hendrickson Department of Comparative Media Studies/Writing August 7, 2020 Certified by: __________________________________________________________________ Tom Levenson Department of Comparative Media Studies/Writing Thesis Advisor Accepted by: _________________________________________________________________ Alan Lightman Department of Comparative Media Studies/Writing Graduate Program of Science Writing Director A BIOGRAPHY OF THE SECOND By Jessica Hendrickson Submitted to the Program in Comparative Media Studies/Writing on August 7, 2020 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Science Writing ABSTRACT A few blinks of an eye. The time it takes a hummingbird to flap its wings 80 times. For a photon of light to travel from Los Angeles to New York and back almost 40-fold. The second has been there since the literal dawn of time, if one exists. But what defines the second? Like a pop star constantly reinventing themselves, the second has undertaken a myriad of identities, first defined as a brief moment in the daily rotation of the earth around its axis. Today, the second is officially defined by over 9 billion oscillations of a cesium atom. -

Sundial™ HQI Pendant Light Fixture

sundial™ HQI Pendant Light Fixture Instructions for Model#1055 & 1056 Important Safety Instructions ....... Page 2 Installation Instructions ....... Page 4 Troubleshooting ....... Page 8 Warranty ....... Page 9 EMAIL: [email protected] WWW.CURRENT-USA.COM 05-2006-JEE Safety Instructions WARNING To guard against injury, basic safety precautions should be observed, including the following: READ AND FOLLOW ALL SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS DANGER To avoid possible electric shock, special care should be taken since water is employed in the use of aquarium equipment. For each of the following situations, do not attempt repairs by yourself; return the appliance to an authorized service facility for service or discard the appliance: 1. If electrical components of the fixture get wet, unplug the appliance immediately. 2. Carefully examine the fixture after installation. It should not be plugged in if there is water on parts not intended to be wet. 3. Do not operate fixture if it has a damaged cord or plug, or if it is malfunctioning or damaged in any manner. See the drip loop instructions on the next page for proper power cord installation. 4. If the plug or receptacle does get wet, DON’T unplug the cord. Disconnect the fuse or circuit breaker that supplies power to the fixture. Then, unplug and examine for presence of water in the receptacle. 5. Close supervision is necessary when any appliance is used by or near children. 6. To avoid injury, do not contact hot parts such as lamps and the like. 7. Always unplug the fixture from an outlet when not in use, before putting on or taking off parts, and before cleaning.