Global DNA Methylation Patterns in Barrett's Esophagus, Dysplastic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

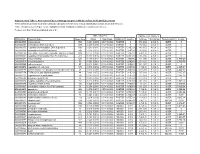

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

The Function and Evolution of C2H2 Zinc Finger Proteins and Transposons

The function and evolution of C2H2 zinc finger proteins and transposons by Laura Francesca Campitelli A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Molecular Genetics University of Toronto © Copyright by Laura Francesca Campitelli 2020 The function and evolution of C2H2 zinc finger proteins and transposons Laura Francesca Campitelli Doctor of Philosophy Department of Molecular Genetics University of Toronto 2020 Abstract Transcription factors (TFs) confer specificity to transcriptional regulation by binding specific DNA sequences and ultimately affecting the ability of RNA polymerase to transcribe a locus. The C2H2 zinc finger proteins (C2H2 ZFPs) are a TF class with the unique ability to diversify their DNA-binding specificities in a short evolutionary time. C2H2 ZFPs comprise the largest class of TFs in Mammalian genomes, including nearly half of all Human TFs (747/1,639). Positive selection on the DNA-binding specificities of C2H2 ZFPs is explained by an evolutionary arms race with endogenous retroelements (EREs; copy-and-paste transposable elements), where the C2H2 ZFPs containing a KRAB repressor domain (KZFPs; 344/747 Human C2H2 ZFPs) are thought to diversify to bind new EREs and repress deleterious transposition events. However, evidence of the gain and loss of KZFP binding sites on the ERE sequence is sparse due to poor resolution of ERE sequence evolution, despite the recent publication of binding preferences for 242/344 Human KZFPs. The goal of my doctoral work has been to characterize the Human C2H2 ZFPs, with specific interest in their evolutionary history, functional diversity, and coevolution with LINE EREs. -

Downloaded from Here

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/017566; this version posted November 19, 2015. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 1 Testing for ancient selection using cross-population allele 2 frequency differentiation 1;∗ 3 Fernando Racimo 4 1 Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA 5 ∗ E-mail: [email protected] 6 1 Abstract 7 A powerful way to detect selection in a population is by modeling local allele frequency changes in a 8 particular region of the genome under scenarios of selection and neutrality, and finding which model is 9 most compatible with the data. Chen et al. [2010] developed a composite likelihood method called XP- 10 CLR that uses an outgroup population to detect departures from neutrality which could be compatible 11 with hard or soft sweeps, at linked sites near a beneficial allele. However, this method is most sensitive 12 to recent selection and may miss selective events that happened a long time ago. To overcome this, 13 we developed an extension of XP-CLR that jointly models the behavior of a selected allele in a three- 14 population tree. Our method - called 3P-CLR - outperforms XP-CLR when testing for selection that 15 occurred before two populations split from each other, and can distinguish between those events and 16 events that occurred specifically in each of the populations after the split. -

Meta-Analysis of Gene Expression in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders

Meta-analysis of Gene Expression in Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders by Carolyn Lin Wei Ch’ng BSc., University of Michigan Ann Arbor, 2011 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Science in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Bioinformatics) The University of British Columbia (Vancouver) August 2013 c Carolyn Lin Wei Ch’ng, 2013 Abstract Autism spectrum disorders (ASD) are clinically heterogeneous and biologically complex. State of the art genetics research has unveiled a large number of variants linked to ASD. But in general it remains unclear, what biological factors lead to changes in the brains of autistic individuals. We build on the premise that these heterogeneous genetic or genomic aberra- tions will converge towards a common impact downstream, which might be reflected in the transcriptomes of individuals with ASD. Similarly, a considerable number of transcriptome analyses have been performed in attempts to address this question, but their findings lack a clear consensus. As a result, each of these individual studies has not led to any significant advance in understanding the autistic phenotype as a whole. The goal of this research is to comprehensively re-evaluate these expression profiling studies by conducting a systematic meta-analysis. Here, we report a meta-analysis of over 1000 microarrays across twelve independent studies on expression changes in ASD compared to unaffected individuals, in blood and brain. We identified a number of genes that are consistently differentially expressed across studies of the brain, suggestive of effects on mitochondrial function. In blood, consistent changes were more difficult to identify, despite individual studies tending to exhibit larger effects than the brain studies. -

UK Lipoedema’ Cohort

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.15.21258988; this version posted June 18, 2021. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY 4.0 International license . Investigation of clinical characteristics and genome associations in the ‘UK Lipoedema’ cohort Authors Dionysios Grigoriadis1*, Ege Sackey1*, Katie Riches2**, Malou van Zanten1**, Glen Brice3, Ruth England2, Mike Mills1, Sara E Dobbins1, Lipoedema Consortium, Genomics England Research Consortium4, Steve Jeffery1, Liang Dong5, David B. Savage5, Peter S. Mortimer1,6, Vaughan Keeley2,7, Alan Pittman1, Kristiana Gordon1,6 ‡, Pia Ostergaard1 ‡ Affiliations 1. Molecular and Clinical Sciences Institute, St George’s University of London, London, UK 2. University Hospitals of Derby and Burton NHS Foundation Trust, Derby, UK 3. South West Thames Regional Genetics Unit, St George's University of London, London, UK 4. Genomics England, London, UK 5. Metabolic Research Laboratories, Wellcome Trust-Medical Research Council Institute of Metabolic Science, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK 6. Dermatology & Lymphovascular Medicine, St George's Universities NHS Foundation trust, London, UK 7. University of Nottingham Medical School, Nottingham, UK *These two authors contributed equally; ** These two authors contributed equally ‡Clinical correspondence to Kristiana Gordon [email protected] and research- related correspondence to Pia Ostergaard, [email protected] NOTE: This preprint reports new research that has not been certified by peer review and should not be used to guide clinical practice. 1 medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.06.15.21258988; this version posted June 18, 2021. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0269772 A1 Califano Et Al

US 20090269772A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2009/0269772 A1 Califano et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 29, 2009 (54) SYSTEMS AND METHODS FOR Publication Classification IDENTIFYING COMBINATIONS OF (51) Int. Cl. COMPOUNDS OF THERAPEUTIC INTEREST CI2O I/68 (2006.01) CI2O 1/02 (2006.01) (76) Inventors: Andrea Califano, New York, NY G06N 5/02 (2006.01) (US); Riccardo Dalla-Favera, New (52) U.S. Cl. ........... 435/6: 435/29: 706/54; 707/E17.014 York, NY (US); Owen A. (57) ABSTRACT O'Connor, New York, NY (US) Systems, methods, and apparatus for searching for a combi nation of compounds of therapeutic interest are provided. Correspondence Address: Cell-based assays are performed, each cell-based assay JONES DAY exposing a different sample of cells to a different compound 222 EAST 41ST ST in a plurality of compounds. From the cell-based assays, a NEW YORK, NY 10017 (US) Subset of the tested compounds is selected. For each respec tive compound in the Subset, a molecular abundance profile from cells exposed to the respective compound is measured. (21) Appl. No.: 12/432,579 Targets of transcription factors and post-translational modu lators of transcription factor activity are inferred from the (22) Filed: Apr. 29, 2009 molecular abundance profile data using information theoretic measures. This data is used to construct an interaction net Related U.S. Application Data work. Variances in edges in the interaction network are used to determine the drug activity profile of compounds in the (60) Provisional application No. 61/048.875, filed on Apr. -

Prenatal Diagnosis of Small Supernumerary Marker Chromosome 10 by Array-Based Comparative Genomic Hybridization and Microdissected Chromosome Sequencing

biomedicines Article Prenatal Diagnosis of Small Supernumerary Marker Chromosome 10 by Array-Based Comparative Genomic Hybridization and Microdissected Chromosome Sequencing Igor N. Lebedev 1,* , Tatyana V. Karamysheva 2 , Eugeny A. Elisaphenko 2, Alexey I. Makunin 3 , Daria I. Zhigalina 1, Maria E. Lopatkina 1 , Gleb V. Drozdov 1, Aleksander D. Cheremnykh 1, Natalia B. Torkhova 1, Gulnara N. Seitova 1, Stanislav A. Vasilyev 1 , Anna A. Kashevarova 1, Ludmila P. Nazarenko 1 and Nikolay B. Rubtsov 2,4 1 Tomsk National Research Medical Center, Research Institute of Medical Genetics, 634050 Tomsk, Russia; [email protected] (D.I.Z.); [email protected] (M.E.L.); [email protected] (G.V.D.); [email protected] (A.D.C.); [email protected] (N.B.T.); [email protected] (G.N.S.); [email protected] (S.A.V.); [email protected] (A.A.K.); [email protected] (L.P.N.) 2 Institute of Cytology and Genetics of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia; [email protected] (T.V.K.); [email protected] (E.A.E.); [email protected] (N.B.R.) 3 Wellcome Sanger Institute, Cambridge CB101SA, UK; [email protected] Citation: Lebedev, I.N.; Karamysheva, 4 Department of Cytology and Genetics, Novosibirsk State University, 630090 Novosibirsk, Russia T.V.; Elisaphenko, E.A.; Makunin, A.I.; * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-38-2251-1109 Zhigalina, D.I.; Lopatkina, M.E.; Drozdov, G.V.; Cheremnykh, A.D.; Abstract: Interpreting the clinical significance of small supernumerary marker chromosomes (sSMCs) Torkhova, N.B.; Seitova, G.N.; et al. -

Genome-Wide Association Studies of Antidepressant Class Response and Treatment-Resistant Depression Qingqin S

Li et al. Translational Psychiatry (2020) 10:360 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-020-01035-6 Translational Psychiatry ARTICLE Open Access Genome-wide association studies of antidepressant class response and treatment-resistant depression Qingqin S. Li 1,ChaoTian2 and David Hinds 2 23andMe Research Team Abstract The “antidepressant efficacy” survey (AES) was deployed to > 50,000 23andMe, Inc. research participants to investigate the genetic basis of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) and non-treatment-resistant depression (NTRD). Genome- wide association studies (GWAS) were performed, including TRD vs. NTRD, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) responders vs. non-responders, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) responders vs. non-responders, and norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor responders vs. non-responders. Only the SSRI association reached the genome-wide significance threshold (p <5×10−8): one genomic region in RNF219-AS1 (SNP rs4884091, p = 2.42 × 10−8,OR= 1.21); this association was also observed in the meta-analysis (13,130 responders vs. 6,610 non-responders) of AES and an earlier “antidepressant efficacy and side effects” survey (AESES) cohort. Meta-analysis for SNRI response phenotype derived from AES and AESES (4030 responders vs. 3049 non-responders) identified another genomic region (lead SNP rs4955665, p = 1.62 × 10−9,OR= 1.25) in an intronic region of MECOM passing the genome-wide significance threshold. Meta-analysis for the TRD phenotype (31,068 NTRD vs 5,714 TRD) identified one additional genomic region (lead SNP rs150245813, p = 8.07 × 10−9,OR= 0.80) in 10p11.1 passing the genome-wide significance threshold. A stronger association for rs150245813 was observed in current study (p = 7.35 × 10−7,OR= 0.79) than the 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; previous study (p = 1.40 × 10−3,OR= 0.81), and for rs4955665, a stronger association in previous study (p = 1.21 × 10−6,OR= 1.27) than the current study (p = 2.64 × 10−4,OR= 1.21). -

1 Novel Expression Signatures Identified by Transcriptional Analysis

ARD Online First, published on October 8, 2009 as 10.1136/ard.2009.108043 Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.2009.108043 on 7 October 2009. Downloaded from Novel expression signatures identified by transcriptional analysis of separated leukocyte subsets in SLE and vasculitis 1Paul A Lyons, 1Eoin F McKinney, 1Tim F Rayner, 1Alexander Hatton, 1Hayley B Woffendin, 1Maria Koukoulaki, 2Thomas C Freeman, 1David RW Jayne, 1Afzal N Chaudhry, and 1Kenneth GC Smith. 1Cambridge Institute for Medical Research and Department of Medicine, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 0XY, UK 2Roslin Institute, University of Edinburgh, Roslin, Midlothian, EH25 9PS, UK Correspondence should be addressed to Dr Paul Lyons or Prof Kenneth Smith, Department of Medicine, Cambridge Institute for Medical Research, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge, CB2 0XY, UK. Telephone: +44 1223 762642, Fax: +44 1223 762640, E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Key words: Gene expression, autoimmune disease, SLE, vasculitis Word count: 2,906 The Corresponding Author has the right to grant on behalf of all authors and does grant on behalf of all authors, an exclusive licence (or non-exclusive for government employees) on a worldwide basis to the BMJ Publishing Group Ltd and its Licensees to permit this article (if accepted) to be published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases and any other BMJPGL products to exploit all subsidiary rights, as set out in their licence (http://ard.bmj.com/ifora/licence.pdf). http://ard.bmj.com/ on October 2, 2021 by guest. Protected copyright. 1 Copyright Article author (or their employer) 2009. -

ZFX Acts As a Transcriptional Activator in Multiple Types of Human

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 10, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press 1 ZFX acts as a transcriptional activator in multiple types of human 2 tumors by binding downstream of transcription start sites at the 3 majority of CpG island promoters 4 5 Suhn Kyong Rhie, Lijun Yao, Zhifei Luo, Heather Witt, Shannon Schreiner, 6 Yu Guo, Andrew A. Perez, and Peggy J. Farnham* 7 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Medicine and the Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, Keck 8 School of Medicine, University of Southern California, Los Angeles 90089, CA, USA. 9 10 * To whom correspondence should be addressed. Tel: +1 323 442 8015; Fax: +1 323 865 1509; Email: 11 [email protected] 12 13 Running title: ZFX activates transcription at CGI promoters 14 Keywords: ZFX, zinc finger proteins, CpG islands, promoters, transcriptional regulation, 15 chromatin structure 1 Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on October 10, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press 1 ABSTRACT 2 High expression of the transcription factor ZFX is correlated with proliferation, tumorigenesis, 3 and patient survival in multiple types of human cancers. However, the mechanism by which ZFX 4 influences transcriptional regulation has not been determined. We performed ChIP-seq in four 5 cancer cell lines (representing kidney, colon, prostate, and breast cancers) to identify ZFX 6 binding sites throughout the human genome. We identified ~9,000 ZFX binding sites and found 7 that the majority of the sites are in CpG island promoters. Moreover, genes with promoters 8 bound by ZFX are expressed at higher levels than genes with promoters not bound by ZFX. -

1 Supplementary Material Figure S1. Volcano Plot of Differentially

Supplementary material Figure S1. Volcano Plot of differentially expressed genes between preterm infants fed own mother’s milk (OMM) or pasteurized donated human milk (DHM). Table S1. The 10 most representative biological processes filtered for enrichment p- value in preterm infants. Biological Processes p-value Quantity of DEG* Transcription, DNA-templated 3.62x10-24 189 Regulation of transcription, DNA-templated 5.34x10-22 188 Transport 3.75x10-17 140 Cell cycle 1.03x10-13 65 Gene expression 3.38x10-10 60 Multicellular organismal development 6.97x10-10 86 1 Protein transport 1.73x10-09 56 Cell division 2.75x10-09 39 Blood coagulation 3.38x10-09 46 DNA repair 8.34x10-09 39 Table S2. Differential genes in transcriptomic analysis of exfoliated epithelial intestinal cells between preterm infants fed own mother’s milk (OMM) and pasteurized donated human milk (DHM). Gene name Gene Symbol p-value Fold-Change (OMM vs. DHM) (OMM vs. DHM) Lactalbumin, alpha LALBA 0.0024 2.92 Casein kappa CSN3 0.0024 2.59 Casein beta CSN2 0.0093 2.13 Cytochrome c oxidase subunit I COX1 0.0263 2.07 Casein alpha s1 CSN1S1 0.0084 1.71 Espin ESPN 0.0008 1.58 MTND2 ND2 0.0138 1.57 Small ubiquitin-like modifier 3 SUMO3 0.0037 1.54 Eukaryotic translation elongation EEF1A1 0.0365 1.53 factor 1 alpha 1 Ribosomal protein L10 RPL10 0.0195 1.52 Keratin associated protein 2-4 KRTAP2-4 0.0019 1.46 Serine peptidase inhibitor, Kunitz SPINT1 0.0007 1.44 type 1 Zinc finger family member 788 ZNF788 0.0000 1.43 Mitochondrial ribosomal protein MRPL38 0.0020 1.41 L38 Diacylglycerol -

T Lymphocytes Mrna, and Protein Expression in Activated Networks Mapped by Global Microrna, Microrna Regulation of Molecular

Downloaded from http://www.jimmunol.org/ by guest on September 24, 2021 is online at: average * The Journal of Immunology published online 25 July 2011 from submission to initial decision 4 weeks from acceptance to publication http://www.jimmunol.org/content/early/2011/07/25/jimmun ol.1101233 MicroRNA Regulation of Molecular Networks Mapped by Global MicroRNA, mRNA, and Protein Expression in Activated T Lymphocytes Yevgeniy A. Grigoryev, Sunil M. Kurian, Traver Hart, Aleksey A. Nakorchevsky, Caifu Chen, Daniel Campbell, Steven R. Head, John R. Yates III and Daniel. R Salomon J Immunol Submit online. Every submission reviewed by practicing scientists ? is published twice each month by Receive free email-alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up at: http://jimmunol.org/alerts http://jimmunol.org/subscription Submit copyright permission requests at: http://www.aai.org/About/Publications/JI/copyright.html http://www.jimmunol.org/content/suppl/2011/07/25/jimmunol.110123 3.DC1 Information about subscribing to The JI No Triage! Fast Publication! Rapid Reviews! 30 days* Why • • • Material Permissions Email Alerts Subscription Supplementary The Journal of Immunology The American Association of Immunologists, Inc., 1451 Rockville Pike, Suite 650, Rockville, MD 20852 Copyright © 2011 by The American Association of Immunologists, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0022-1767 Online ISSN: 1550-6606. This information is current as of September 24, 2021. Published July 25, 2011, doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1101233 The Journal of Immunology MicroRNA Regulation of Molecular Networks Mapped by Global MicroRNA, mRNA, and Protein Expression in Activated T Lymphocytes Yevgeniy A. Grigoryev,* Sunil M. Kurian,* Traver Hart,* Aleksey A.