Bruce Katz's Full Remarks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard C. Brower, Boston University with Many Slides from Kate Clark, NVIDIA

Past and Future of QCD on GPUs Richard C. Brower, Boston University with many slides from Kate Clark, NVIDIA High Performance Computing in High Energy Physics CCNU Wahan China, Sept 19, 2018 Optimize the Intersection Application: QCD Algorithms: Architecture: AMG GPU Question to address • How do we put Quantum Field on the computer? • How to Maximize Flops/$, bandwidth/$ at Min Energy? • How to implement fastest algorithms: Dirac Sovlers, Sympletic Integrators, etc ? Standard Lattice QCD Formulation i d3xdt[ F 2 + (@ iA + m) ] Path Integral = 2A(x) (x) e− g2 µ⌫ µ µ − µ D Z R 1.Complex time for probability it x ! 4 iaAµ 2. Lattice Finite Differences (@µ iAµ) (x) ( x+ˆµ e x)/a − ! − d d e xDxy(A) y Det[D] 3. Fermionic integral − ! Z Det[D] dφdφ e φx[1/D]xyφy 4.Bosonic (pseudo- Fermions) ! − Z ij 1 γµ Lattice Dirac (x) − U ab(x) (x +ˆµ) ia 2 µ jb Color Dimension: a = 1,2,3 μ=1,2,…,d Spin i = 1,2,3,4 x x+ ➔ µ axis 2 x SU(3) Gauge Links ab ab iAµ (x) Uµ (x)=e x1 axis ➔ Quarks Propagation on Hypercubic Lattice* • Dominate Linear Algebra : Matrix solver for Dirac operator. • Gauge Evolution: In the semi-implicit quark Hamiltonian evolution in Monte vacuum Carlo time. u,d,s, proto u, • Analysis: proto d * Others: SUSY(Catteral et al), Random Lattices(Christ et al), Smiplicial Sphere (Brower et al) Byte/flop in Dirac Solver is main bottleneck • Bandwidth to memory rather than raw floating point throughput. • Wilson Dirac/DW operator (single prec) : 1440 bytes per 1320 flops. -

Science Fiction on American Television

TV Sci-Fi 16 + GUIDE This and other bfi National Library 16 + Guides are available from http://www.bfi.org.uk/16+ TV Sci-Fi CONTENTS Page IMPORTANT NOTE................................................................................................................. 1 ACCESSING RESEARCH MATERIALS.................................................................................. 2 APPROACHES TO RESEARCH, by Samantha Bakhurst ....................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION by Sean Delaney ......................................................................................... 6 AMERICAN TELEVISION........................................................................................................ 8 SCIENCE FICTION ON AMERICAN TELEVISION ................................................................. 9 AUDIENCES AND FANS......................................................................................................... 11 ANDROMEDA ......................................................................................................................... 12 BABYLON 5 ............................................................................................................................ 14 BATTLESTAR GALACTICA................................................................................................... 17 FARSCAPE ............................................................................................................................. 19 THE IRWIN ALLEN QUARTET • VOYAGE TO THE BOTTOM OF THE SEA..................................................................... -

A Quantum Leap for AI

TRENDS & CONTROVERSIES A quantum leap for AI By Haym Hirsh Rutgers University [email protected] November 1994 saw the near-simultaneous publication of two papers that threw the notion of computing on its head. On November 11, 1994, a paper by Leonard Adleman appeared in Science demonstrating that a vial of DNA fragments can serve as a computer for solving instances of the Hamiltonian path problem. Less than two weeks later, Peter Shor Quantum computing and AI presented a paper in Santa Fe, New Mexico, at the 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations Subhash Kak, Louisiana State University of Computer Science, demonstrating how a quantum computer could be used to factor large Every few years, we hear of a new tech- numbers in a tractable fashion. Both these publications showed how nontraditional models nology that will revolutionize AI. After of computation had the potential to effectively solve problems previously believed to be careful reflection, we find that the advance intractable under traditional models of computation. However, the latter work, using a quan- is within the framework of the Turing tum model of computation proposed by Richard Feynmann and others in the early 1980s, machine model and equivalent, in many resonated well with AI researchers who had been coming to terms with Roger Penrose’s cases, to existing statistical techniques. But 1989 book The Emperor’s New Mind. In this book (and its sequel, Shadows of the Mind: A this time, in quantum computing, we seem Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness, which appeared in paperback form only a to be on the threshold of a real revolution— month before these papers), Penrose challenges the possibility of achieving AI via traditional a “quantum” leap—because it is a true “Turing-equivalent” computation devices, conjecturing that the roots of intelligence can be frontier beyond classical computing. -

Quantum Leap” Truancy and Dropout Prevention Programs Mount Anthony Union High School, Bennington Vermont

Final Evaluation Report “Quantum Leap” Truancy and Dropout Prevention Programs Mount Anthony Union High School, Bennington Vermont Monika Baege, EdD Susan Hasazi, EdD H. Bud Meyers, PhD March 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Purpose of the Study............................................................................................................1 Methodology........................................................................................................................3 Qualitative Findings.............................................................................................................5 Program Descriptions......................................................................................................5 Views and Experiences of Stakeholders.........................................................................6 Fostering Self-Determination.....................................................................................6 Variety of Supportive Programs ................................................................................9 Utilizing Experiential Learning ...............................................................................14 Vital Connection with Bennington College and the Larger Community ................21 Inspired and Collaborative Leadership Focused on Individual Relationships.........25 Stakeholders’ Additional Advice for Replication, Sustainability, Improvements........27 -

RACSO Motion Pictures Announces Next Project

CONTACT: CHRISTOPHER ALLEN PRESS RELEASE 317.418.4841 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE [email protected] RACSO Motion Pictures Announces Next Project INDIANAPOLIS, Ind. – *Award Winning Filmmaker Christopher Allen has announced the title of his company’s next film production, a fan based effort to re-launch the popular “Quantum Leap” television series that ran on NBC from 1989 to 1993. Indianapolis based RACSO Motion Pictures is targeting 2008 as to when principal photography will begin. “Whenever people hear of a fan based effort, or fanfilm, they immediately think of a high school kid with mom and dad’s hand held video camera. This is clearly not the case.” said Allen from his studio in Carmel, Indiana. “My last fan effort (award winning Star Trek vs. Batman) opened more doors for my career than everything else prior to it. No one should underestimate the capability of what fan based films can do, if done professionally.” Allen will enlist a wide array of Indianapolis talent to help continue the story of Dr. Sam Beckett, who ironically is from a fictitious town in Indiana. Once completed, Allen hopes to use “Quantum Leap: A Leap to Di for” to persuade the science fiction broadcasting networks to re- launch the popular franchise. “I hope that the story is what will ensure the film’s acceptance by the fans. It centers on Dr. Beckett’s journey to 1997, where he is presented with the likelihood of saving the life of Princess Diana.” Allen said. “That one possibility is something I believe everyone can identify with.” Allen went on to add. -

Horacio Torres B

Horacio Torres b. 1924 Livorno, Italy - d. 1976 New York City Of the many painters who studied with his father, the great Constructivist artist Joaquín Torres-García, Horacio Torres made the quantum leap into the Contemporary art world of abstract and expressionistic painters in New York's 1970s. That he did so with figurative canvases was a singular achievement. Taken under the wing of the critic Clement Greenberg, who understood that Horacio's work was really about painting and was thoroughly modern, Horacio explored the thunderous territory of Titian, Velasquez and late Goya with a unique background of skill and aesthetic education in a contemporary way. Thus the series of headless nudes and of figures with faces obscured, make clear his painterly intentions and concerns. His monumental canvases are wondrous exercises of painted imagination formed with the structure of the depicted figure, but they are not about nudes, they are about painting. Public Collections Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Museum of Modern Art, New York Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C. Davis Museum, Wellesley College, Massachusetts Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Massachusetts Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas Brandeis University Museum, Waltham, Massachusetts Hastings College, Nebraska Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence, New York Musée d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France Edmonton Museum, Alberta, Canada Biblioteca Nacional, Montevideo, Uruguay Museo Blanes, Montevideo, Uruguay Main Solo Exhibitions (partial listing) 2017 Horacio Torres: Nudes, Cecilia de Torres, Ltd., New York 2016 Horacio Torres: Early Works, Cecilia de Torres, Ltd., New York 1999 Salander-O’Reilly Gallery, New York Cecilia de Torres, Ltd. -

Or “Show Me Pictures of a Pup.”? | Whats Next

1/10/2021 “How many ounces in a cup?” or “Show me pictures of a pup.”? | Whats Next What’s next Enterprise “How many ounces in a cup?” or “Show me pictures of a pup.”? In order for Conversational AI to work, Natural Language Understanding needs to see both context and the human condition. Ken Arakelian helps us understand what happens when speech technology only gets part of the picture. Ken Arakelian Posted December 6, 2018 1/5 1/10/2021 “How many ounces in a cup?” or “Show me pictures of a pup.”? | Whats Next Quantum Leap There was a TV show called “Quantum Leap” where Sam Beckett, a scientist, is trapped in a time travel experiment gone wrong and “leaps” into a different person’s body each week. Every episode starts with the moments after he leapt into the next body and he found himself in a funny (or dangerous) situation. Sam had to make a quick decision on how to get out of it; this is basically what happens when you say, “Alexa, how many ounces in a cup?” Alexa wakes up with little context and makes a split-second decision about the question you’re asking. What makes Alexa’s job harder than Sam Beckett’s is that Sam was a person and always leapt into a human body and Alexa doesn’t understand what it means to be human. Out of context Let’s leap into a situation and try to understand what we’re seeing when we only get a snippet out of context. -

Quantum Leap - Kentucky Bluegrass TURF QUALITY Is a Compact Midnight-Type Derived from Midnight X Limou- Sine

KENTUCKY BLUEGRASS ( Rating: 1- 9, 1: Poor; 9: Excellent ) Quantum Leap - Kentucky Bluegrass TURF QUALITY is a Compact Midnight-type derived from Midnight x Limou- sine. Quantum Leap offers the best qualities of both varieties DARK GREEN COLOR including very dark green color and density, along with the HEAT TOLERANCE aggressive growth of Limousine. SHADE TOLERANCE Versatility is a key strength of Quantum Leap. It has demon- WEAR TOLERANCE strated superior turf quality at all levels of maintenance. This makes Quantum Leap the perfect choice for all applications 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 including sod production, golf course fairways and tees, sports fields and home lawns. Wherever a dense, attractive turf is desired, Quantum Leap is the one to choose. Its excep- NTEP 2001-2005 NTEP 2001-2005 tional sod strength makes it stand out when wear is an issue. WEAR TOLERANCE SPRING GREENUP @8 Transitional Locations The dark, rich color of Quantum Leap provides an attractive Limousine 8.2 Nu Destiny 6.0 apperance, even under reduced nitrogen fertilization rates. Quantum Leap 7.3 Blue Velvet 5.8 While moderately aggressive, Quantum Leap is not as thatch-prone as earlier aggressive bluegrasses. This trans- Midnight 7.2 Quantum Leap 5.7 lates into better utilization of resources like moisture and Baron 6.3 Midnight 5.4 fertilizer. Quantum Leap has also shown excellent resistance Nuglade 6.0 Baron 4.7 to many turfgrass diseases like necrotic ring spot and melting out, as well as pests like chinch bugs so inputs are Shamrock 5.5 Shamrock 4.6 reduced even more. -

Curriculum Vita of Dr. Diola Bagayoko

In complex processes, good faith and good will are generally not enough; pertinent knowledge, know- how, and sustained efforts are necessary more often than not. The full vita of D. Bagayoko is available upon request, with all the 90+ pages listing all grants, publications, and presentations. Diola Bagayoko, Ph.D. Southern University System Distinguished Professor of Physics, Director, the Timbuktu Academy and the Louis Stokes Louisiana Alliance for Minority Participation (LS-LAMP), Dean, the Dolores Margaret Richard Spikes Honors College, Southern University and A&M College in Baton Rouge (SUBR). Email: [email protected] or [email protected] Mailing Addresses: P. O. Box 11776, SUBR, Baton Rouge, La 70813 or Room 232/241 W. James Hall, Southern University and A&M College, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 70813 - Telephone: 225-771-2730/ -4845 Fax: 225-771-4341/ -4848 [Mobile Phone: 001-225-205-7482] Web Page: http://www.phys.subr.edu/PhysicsCurrent/faculty/bagayoko/ A1. EDUCATION AND EMPLOYMENT Education Philosophy doctorate (Ph.D.), Louisiana State University (LSU), Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1983, Theoretical Solid State Physics, i.e., Condensed Matter Theory. Master’s degree (MS), Solid State Physics, Lehigh University, Bethlehem, PA, 1978. BS, Physics and Chemistry, Ecole Normale Superieure (ENSup) de Bamako, Bamako, Mali, 1973. Formal training in the theory and practice of Teaching and Learning, ENSup, 1969-1973. Employment Dean, the Dolores Margaret Richard Spikes Honors College (2015-Present). Southern University System Distinguished -

SUPREME COURT of LOUISIANA 98-C-1122, 98-C-1133, and 98-C-1134

SUPREME COURT OF LOUISIANA 98-C-1122, 98-C-1133, and 98-C-1134 SENATOR J. LOMAX “MAX” JORDAN versus LOUISIANA GAMING CONTROL BOARD and MURPHY J. “MIKE” FOSTER Consolidated With SENATOR RONALD C. BEAN versus LOUISIANA GAMING CONTROL BOARD and RIVERGATE DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION KNOLL, J., Dissenting. Finding that the operating contract approved by the Board on January 28, 1998, is a new contract, I dissent from the majority opinion. Because of this finding, all other issues are pretermitted in this discussion. The majority totally ignores the laws of obligations and cloaks its position in terms of a renegotiation of a contract placed in bankruptcy to create a legal fiction as though this bankruptcy status immunizes the original contract from the Louisiana law of obligations. A simple application of our contract law demonstrates that the contract at issue is a new contract. La.Civ. Code art. 1756 defines a legal obligation: An obligation is a legal relationship whereby a person, called the obligor, is bound to render a performance in favor of another, called the obligee. Performance may consist of giving, doing, or not doing something. In the proposed contract, HJC, the original obligor, is released and forever discharged from any and all matter of claims, and all of its debt under the original contract with the State is extinguished. A new obligor, JCC, will be legally bound to perform under new terms and conditions. The new obligee is the Board, which was created by Act 7 of 1996 and who replaces the old obligee, the self-funded LEDGC which was created under Act 384 of 1992. -

Quantum Information Science and Engineering at NSF

Quantum Information Science and Engineering at NSF C. Denise Caldwell Division Director, Division of Physics Co-Chair NSF Quantum Stewardship Steering Committee https://www.nsf.gov/mps/quantum/quantum_research_at_nsf.jsp https://www.nsf.gov/news/factsheets/Factsheet_Quantum-proof7_508.pdf 1 NSF and the NQI Sec. 301: The Director of the National Science Foundation shall carry out a basic research and education program on quantum information science and engineering, including the competitive award of grants to institutions of higher education or eligible nonprofit organizations (or consortia thereof). Sec. 302: The Director of the National Science Foundation, in consultation with other Federal departments and agencies, as appropriate, shall award grants to institutions of higher education or eligible nonprofit organizations (or consortia thereof) to establish at least 2, but not more than 5, Multidisciplinary Centers for Quantum Research and Education (referred to in this section as ‘‘Centers’’). 2 Building a Convergent Quantum Community Convergent Quantum Centers Challenge Institutes & Foundries Transformational Collaborative Research TAQS Small Team Awards, 19 awards, totaling $35.5M Quantum Workforce Development Summer Schools, Triplets, Faculty Fellows, Q2Work Capacity Building Across Disciplines 56 awards made in FY 2016-18, totaling over $35M Foundational Investments in QIS – 40 Years & Counting More than 2000 awards & 1200 unique PIs in multiple areas 3 Quantum Leap Challenge Institutes (QLCI) • Support large-scale projects driven by a cross-disciplinary challenge research theme for the frontiers of quantum information science and engineering. • Maintain a timely and bold research agenda aimed at making breakthroughs on compelling challenges in a 5-year period. • Conceptualize, develop, and implement revolutionary new approaches and technologies for quantum information processing. -

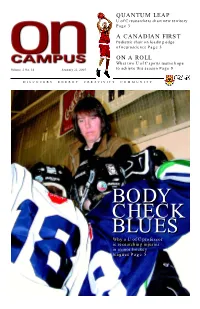

Quantum Leap a Canadian First on a Roll

QUANTUM LEAP U of C researchers chart new territory Page 3 A CANADIAN FIRST Pediatric chair on leading edge of neuroscience Page 5 ON A ROLL What two U of C sports teams hope Volume 2 No. 14 January 21, 2005 to achieve this season Page 9 DISCOVERY ENERGY CREATIVITY COMMUNITY BODYBODY CHECKCHECK BLUESBLUES WhyWhy aa UU ofof CC professorprofessor isis researchingresearching injuriesinjuries inin minorminor hockeyhockey leaguesleagues PagePage 55 on CAMPUS NEITHER RAIN NOR SNOW . This week, a nod to the folks who work outside, like Diane White and Lynnette White kept the grounds neat and tidy at 8 a.m. even Marek Walkowiak shovelled parking attendant Jeremy Jeremiah. during the recent cold spell. / Photos by Ken Bendiktsen the walks. TO THE POINT YOUR ALUMNI Haskayne the final round, the Randall students triumph teams were given five reappointed Dean at international hours to analyse a new of the Faculty of Home-schooling business business case and Social Sciences competition make a 15-minute Power Point presenta- Dr. Stephen Randall Seventeen Haskayne tion on its solution. has been reappointed away from home BComm students as Dean of the Faculty upheld a 27-year of Social Sciences for a Diane winning streak, collect- Alumnus to Run final two-year term, ing five medals in the in Ward 10 beginning on July 1, Swiatek eight-event Inter- 2005. Collegiate Business Calgary’s Ward 10 has ”I believe that Dr. created Competition (ICBC) at been marred in contro- Randall will continue to Queen’s University in versy over the last be a highly effective a school Ontario last weekend.