Bruckner's Ninth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

May 10, 2018 TERRENCE HOWARD, MARTHA STEWART, DONALD

May 10, 2018 TERRENCE HOWARD, MARTHA STEWART, DONALD RUMSFELD, BRET BAIER, ALAN CUMMING, ERIKA JAYNE, HOT TOPICS AND MORE, ON ‘THE VIEW,’ MAY 14 – 18 Alyssa Milano Guest Co-hosts, May 18 Celebrating Season 21, “The View” (11:00 a.m.- 12:00 p.m. EDT) is the place to be heard with live broadcasts five days a week. Hilary Estey McLoughlin serves as senior executive producer with Candi Carter and Brian Teta as executive producers. “The View” is directed by Sarah de la O. For breaking news and updated videos, follow “The View” (@theview) and Whoopi Goldberg (@whoopigoldberg), Joy Behar (@joyvbehar), Paula Faris (@paulafaris), Sara Haines (@sarahaines), Sunny Hostin (@sunny) and Meghan McCain (@meghanmccain) on Twitter. Scheduled guests for the week of MAY 14 – 18 are as follows (subject to change): Monday, May 14 – Terrence Howard (“Terrence Howard's Fright Club” and “Empire”); “View Your Deal” with hottest items at affordable prices Tuesday, May 15 – Martha Stewart (Martha Stewart Pets) Wednesday, May 16 – The Political View with former U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld (book, “When the Center Held: Gerald Ford and the Rescue of the American Presidency”) Thursday, May 17 – The Political View with Bret Baier (book, “Three Days in Moscow: Ronald Reagan and the Fall of the Soviet Empire”; and “Special Report” with Bret Baier); Alan Cumming (“Instinct” and “Show Dogs”) Friday, May 18 – Guest co-host Alyssa Milano; Erika Jayne (book, “Pretty Mess”; “The Real Housewives of Beverly Hills”) LINK: https://bit.ly/2jPUUXw TWEET: https://ctt.ac/fcBx3 ABC Media Relations Lauri Hogan (212) 456-6358 [email protected] Facebook: @TheView Twitter: @TheView Instagram: @theviewabc Hashtag: #theview For more information, follow ABC News PR on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. -

FLYING on the WINGS of HEROES by Archon Lynn Swann, Rho Boulé

Cover Story Archon Brown on the set of Red Tails with actors (from right) Leslie Odom, Jr., Ne-Yo, Kevin Phillips, Elijah Kelley and David Oyelowo FLYING ON THE WINGS OF HEROES By Archon Lynn Swann, Rho Boulé ince joining the Boulé fifteen years ago, I have had back on it now, I see that that wasn’t such a bad situation. occasion to meet a host of distinguished and brilliant But I never knew Les Williams was a Tuskegee Airman Smen. It has been an honor. Yet nothing could have until I saw him in a documentary titled Double Victory, prepared me for the opportunity I had earlier this year which was produced by George Lucas and the Lucasfilm when I met men of history – Boulé members that were team working on the upcoming film Red Tails, about the Tuskegee Airmen, perhaps some of the most important combat missions flown by the 332nd Fighter Group. Les, I and legendary figures in the history of the U.S. Armed found out, was the first African American commissioned Services during World War II. as a bomber pilot, serving in the 477th Composite Group. Little did I know that I had a personal connection to The fact that Les never told me about his experience these heroic men. Back when I was just a fourth grader, – I took dance classes from him from fourth grade until my mother decided that I was going to take dance classes. I graduated from Junipero Serra High School – says She didn’t ask me – she just drove me down to the Les much about him and about the other men who served. -

Link to Article

San Diego Symphony News Release www.sandiegosymphony.org Contact: April 15, 2016 Stephen Kougias Director of Public Relations 619.615.3951 [email protected] To coincide with Comic-Con, San Diego Symphony Presents: Final Symphony: The Ultimate Final Fantasy Concert Experience; Thurs July 21; 8PM The Legend of Zelda: Symphony of the Goddesses – Master Quest; Friday, July 22; 8PM Concerts to be performed at Downtown’s Jacobs Music Center – Copley Symphony Hall; tickets on sales now. Final Symphony: The Ultimate Final Fantasy Concert Experience, the concert tour featuring the music of Final Fantasy VI, VII and X will make its debut this summer stopping in San Diego on Thursday, July 21 with the San Diego Symphony performing the musical score live on stage. Following sell-out concerts and rave reviews across Europe and Japan, Final Symphony takes the celebrated music of composers Nobuo Uematsu and Masashi Hamauzu and reimagines it as a fully realized, orchestral suites including a heart-stirring piano concerto based on Final Fantasy X arranged by composer Hamauzu himself, and a full, 45-minute symphony based on the music of Final Fantasy VII. “We’ve been working hard to bring Final Symphony to the U.S. and I’m absolutely delighted that fans there will now be able to see fantastic orchestras perform truly symphonic arrangements of some of Nobuo Uematsu and Masashi Hamauzu’s most beloved themes,” said producer Thomas Böcker. “I’m very excited to see how fans here react to these unique and breathtaking performances. This is the music of Final Fantasy as you’ve never heard it before.” Also joining will be regular Final Symphony conductor Eckehard Stier and talented pianist Katharina Treutler, who previously stunned listeners with her virtuoso performance on the Final Symphony album, recorded by the world famous London Symphony Orchestra at London’s Abbey Road Studios, and released to huge critical acclaim in February 2015. -

London's Symphony Orchestra

London Symphony Orchestra Living Music Sunday 7 May 2017 7pm Barbican Hall SHOSTAKOVICH SYMPHONY NO 15 Mussorgsky arr Rimsky-Korsakov Prelude to ‘Khovanshchina’ Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto INTERVAL London’s Symphony Orchestra Shostakovich Symphony No 15 Sir Mark Elder conductor Anne-Sophie Mutter violin Concert finishes approx 9.10pm Generously supported by Celia & Edward Atkin CBE 2 Welcome 7 May 2017 Welcome Living Music Kathryn McDowell In Brief A warm welcome to this evening’s LSO concert at BMW LSO OPEN AIR CLASSICS 2017 the Barbican, where we are joined by Sir Mark Elder for an all-Russian programme of works by Mussorgsky, The London Symphony Orchestra, in partnership with Tchaikovsky and Shostakovich. BMW and conducted by Valery Gergiev, performs an all-Rachmaninov programme in London’s Trafalgar The concert opens with the prelude to Mussorgsky’s Square on Sunday 21 May, the sixth concert in the opera Khovanshchina, in an arrangement by fellow Orchestra’s annual BMW LSO Open Air Classics Russian composer, Rimsky-Korsakov. Then we are series, free and open to all. delighted to see Anne-Sophie Mutter return as the soloist in Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, before lso.co.uk/openair Sir Mark Elder concludes the programme with Shostakovich’s final symphony, No 15. LSO WIND ENSEMBLE ON LSO LIVE I hope you enjoy the performance. I would like to take this opportunity to welcome Celia and The new recording of Mozart’s Serenade No 10 Edward Atkin, and to thank them for their generous for Wind Instruments (‘Gran Partita’) by the LSO support of this evening’s concert. -

Leslie Odom, Jr

2019 MARCH 40TH SEASON LESLIE ODOM, JR. 2018-19 PACIFIC SYMPHONY POPS Matt Catingub, conductor AN EVENING WITH LESLIE ODOM, JR. Leslie Odom, Jr., vocalist Friday, March 15, 2019 @ 8 p.m. Saturday, March 16, 2019 @ 8 p.m. Segerstrom Center for the Arts Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall OFFICIAL HOTEL OFFICIAL TV STATION OFFICIAL MUSIC STATION 12 MARCH 2019 | 40TH SEasON PacificSymphony.org LESLIE ODOM, JR. MaTT CaTINGUB Catingub had made his solo singing debut at the Frank Sinatra Celebration Multifaceted performer Matt Catingub wears at New York City’s legendary Carnegie Leslie Odom, Jr. was many hats: saxophonist, Hall and as a result of his performance previously seen on woodwind artist, there, the Concord Jazz CD Gershwin Broadway starring conductor, pianist, 100 was conceived. Catingub also wrote as Aaron Burr in the vocalist, performer, and performed the music for the George blockbuster hit musical, composer and arranger. Clooney film, “Goodnight and Good Luck,” Hamilton. Catingub is the artistic made an onscreen appearance as the He is a Grammy director and co-founder leader of the band, created all of the Award- winner as a principal soloist of the Macon Pops in Macon, Georgia, arrangements and played tenor sax in on Hamilton’s Original Broadway Cast and recently the artistic director and the movie and on the CD. The Soundtrack Recording, which won the 2015 award for conductor of the Glendale Pops in Los for “Goodnight and Good Luck,” featuring Best Musical Theater Album. Angeles, the Hawaii Pops in Honolulu, as Catingub and vocalist Diane Reeves, won Odom, Jr. -

KSO Welcomes Broadway Star Leslie Odom Jr May

KNOXVILLE SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA POPS PRESENTS Leslie Odom, Jr. in concert Tony and Grammy Award Winner, Leslie Odom, Jr. originated the role of Aaron Burr in the smash-hit 'Hamilton' and will make his Knoxville Symphony debut with a feel-good program of jazz standards and familiar Broadway hits on May 11th. Knoxville, TN – April 29, 2019– The Knoxville Symphony Orchestra concludes its Pops Series with Leslie Odom, Jr. This concert will take place on Saturday, May 11 at 8:00 p.m. at the Civic Auditorium. View seats and purchase tickets. This concert is sponsored by Regal. Tony and Grammy Award- winning performer, Leslie Odom Jr., has taken the entertainment world by storm across a variety of media – spanning Broadway, television, film, and music. Best known for his breakout role as ‘Aaron Burr’ in the smash hit Broadway musical, Hamilton, Odom Jr. received a 2015 Drama Desk Award nomination and won the Tony Award for “Best Actor in a Musical” for his performance. He also won a Grammy Award as a principal soloist on the original cast recording. Odom, Jr. made his Broadway debut at the age of 17 in “Rent” before heading to Carnegie Mellon University’s prestigious School of Drama, where he graduated with honors. On the small screen, Odom, Jr. is best known for his portrayal of ‘Sam Strickland’ in the NBC musical series, “Smash,” and his recurring role as ‘Reverend Curtis Scott’ on “Law & Order: SVU.” He’s also appeared in episodes of “Gotham,” “Person of Interest,” “Grey’s Anatomy,” “House of Lies,” “Vanished” and “CSI: Miami.” On the big screen he starred in the 2012 film, “Red Tails,” opposite Terrence Howard, Cuba Gooding Jr., and David Oyelowo. -

Detailed Tables the Oscars Table of Contents

The Oscars Detailed tables TThhee OOssccaarrss TTaabbllee ooff CCoonntteennttss qE1. As you may know, the Oscar Awards for theatre movies produced in 2005 will be broadcast this coming Sunday night on TV. Do you plan to watch ...?...................................................................................................................... 1 qE2A. Regardless of whether or not you have seen any of these movies or plan to watch the Academy Awards on TV, please give your best guess of who should win in each category. Best motion picture of the year....................... 2 qE2b. Performance by an actress in a leading role ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 qE2c. Performance by an actor in a leading role ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 qE3. How would you classify yourself? ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

MIRACLE on 42ND STREET” a Documentary About Manhattan Plaza

Media Press Kit “MIRACLE ON 42ND STREET” A documentary about Manhattan Plaza LOG LINE The story oF Manhattan Plaza - a housing complex in New YorK City For people in the perForming arts, and how it led to the revitalization of midtown Manhattan. Miracle on 42nd Street is the First film to focus on the story of affordable housing for artists. SYNOPSIS Miracle on 42nd Street is a one-hour documentary about the untold history and impact of the Manhattan Plaza apartment complex in New YorK City. Starting with the bacKground of the blighted Hell's Kitchen neighborhood and the building’s initial commercial Failure in the mid- 1970s, the story recounts how – in a moment oF bold inspiration or maybe desperation - the buildings were “re-purposed” as subsidized housing For people who worKed in the perForming arts, becoming one of the First intentional, government supported, afFordable housing For artist residences. The social experiment was a resounding success in the lives oF the tenants, and it led the way in the transformation of the midtown neighborhood, the Broadway theater district and local economy. The Film makes a compelling case For the economic value of the arts and artists in America. The success oF Manhattan Plaza has become a role model For similar experiments, which the Film Features, around the country, in places like Ajo, Arizona, Providence, Rhode Island and Rahway, New Jersey. Narrated by acclaimed actor/writer Chazz Palminteri, Miracle on 42nd Street features on-camera interviews with people whose lives were positively impacted by the complex, including Alicia Keys, Terrence Howard, Donald Faison, Larry David and Samuel L JacKson, Angela Lansbury, Giancarlo Esposito, and many others. -

89Th Oscars® Nominations Announced

MEDIA CONTACT Academy Publicity [email protected] January 24, 2017 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Editor’s Note: Nominations press kit and video content available here 89TH OSCARS® NOMINATIONS ANNOUNCED LOS ANGELES, CA — Academy President Cheryl Boone Isaacs, joined by Oscar®-winning and nominated Academy members Demian Bichir, Dustin Lance Black, Glenn Close, Guillermo del Toro, Marcia Gay Harden, Terrence Howard, Jennifer Hudson, Brie Larson, Jason Reitman, Gabourey Sidibe and Ken Watanabe, announced the 89th Academy Awards® nominations today (January 24). This year’s nominations were announced in a pre-taped video package at 5:18 a.m. PT via a global live stream on Oscar.com, Oscars.org and the Academy’s digital platforms; a satellite feed and broadcast media. In keeping with tradition, PwC delivered the Oscars nominations list to the Academy on the evening of January 23. For a complete list of nominees, visit the official Oscars website, www.oscar.com. Academy members from each of the 17 branches vote to determine the nominees in their respective categories – actors nominate actors, film editors nominate film editors, etc. In the Animated Feature Film and Foreign Language Film categories, nominees are selected by a vote of multi-branch screening committees. All voting members are eligible to select the Best Picture nominees. Active members of the Academy are eligible to vote for the winners in all 24 categories beginning Monday, February 13 through Tuesday, February 21. To access the complete nominations press kit, visit www.oscars.org/press/press-kits. The 89th Oscars will be held on Sunday, February 26, 2017, at the Dolby Theatre® at Hollywood & Highland Center® in Hollywood, and will be televised live on the ABC Television Network at 7 p.m. -

Golden Receiver: Summer Fashion Five Minutes with Goes to School Mohamed Massaquoi

the athens Still kickin' & still free INSIDE: THREE SIX MAFIA • HORROR POPS • THE WATSON TWINS • G.G. ELVIS AND THE TCP BAND • FIVE FINGER DEATH PUNCH BLUR • JOHNATHAN RICE • BUMBLEFOOT • KEN AUGUST 2008, VOL 1, ISSUE 2 MAGAZine WILL MORTON • KENI THOMAS & MORE!!!! gas guzzlers Are pump prices draining sec downtown commerce? preview 2008 KATY PERRY KISSED A GIRL (AND SHE LIKED IT) GOLDEN RECEIVER: summer fashion FIVE MINUTES WITH goes to school MOHAMED MASSAQUOI the legend of tilly &the wall>> INTRODUCING THE NEW FLY 150 Performance and style on two wheels. 150cc, single cylinder, four-stroke engine, automatic transmission, 12” wheels, underseat storage for full size helmet. TOP GEAR MOTORSPORTS 4215 Atlanta Hwy, Bogart, GA 30622 Phone: 706-548-9445 www.topgearmotorsports.com © PIAGGIO GROUP AMERICAS 2008. PIAGGIO® AND VESPA® ARE WORLDWIDE REGISTERED TRADEMARKS OF THE PIAGGIO GROUP OF COMPANIES. OBEY LOCAL TRAFFIC SAFETY LAWS AND ALWAYS WEAR A HELMET, APPROPRIATE EYEWEAR AND PROPER APPAREL. WELCOME BACK STUDENTS! CHECK OUT OUR NEW FALL SPECIALS! FRIDAY and SATURDAY HAPPY HOUR UNTIL 11 749 W. BROAD ST. 706.543.7701 • DANIELSVILLE 706.795.5400 KROGER SHOPPING CENTER, COLLEGE STATION RD. 706.549.6900 HOMEWOOD HILLS SHOPPING CENTER, PRINCE AVE. 706.227.2299 WATKINSVILLE 706.7669.0778 BLUR CONTENTS BLUR CONTENTS FEATURES DEPARTMENTS KATY PERRY MUSIC KISSED SPOTLIGHTS: GENRE COVERAGE FROM METAL TO COUNTRY 9 THE BUZZ: THE LATEST IN NEWS AND RUMORS 28 A GIRL EAR CANDY: ALBUM REVIEWS 30 20 EDITOR’S PLAYLIST:10 TUNES WE CAN’T STOP LISTENING TO -

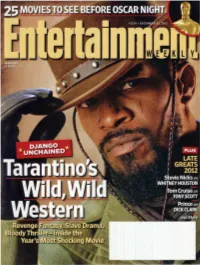

Django Unchained (Rated R) Under the Tree on Dec

-UENTIN TARANTINO knows the.secret of yuletide gift giving: Get them something they wouldn't get thf ~selves. After all, who but Tarantino, the man who achine-gunned Hitler's face off in his WWII remix (jfiourious Basterds, would think of laying a hyper- violent all-star slave-revenge-Western fairy tale like Django Unchained (rated R) under the tree on Dec. 25? Like so,many other presents, Django was wrapped just in time. After seven months of production, additional reshoots, weather complications, a revolving-door cast list, a sudden death, and a sprint to the finish in the editing room, Tarantino has managed to deliver the film for its festive release date. With that long, dusty trail now behind , him, the filmmaker slumps beneath a foreign-language . ' \Pulp Fiction poster in a corner of Do Hwa, the Korean l ' l ◄ , 1 , ~staurant he co-owns in Manhattan's West Village, and ' t av mits he's tired. "It's been a long journey, man." I i I , 26 I EW.COM Dec,a 21, 2012 (Clockwise from far left) Foxx; Foxx, Leonardo DiCaprio, and Waltz; Kerry Washington and Samuel L. Jackson; Washington Keep in mind: An exhausted Quentin Tarantino, even at 49 and a long way from his wunderkind years, is still as energetic as a regular person would be after two strong coffees. And he's char acteristically enthusiastic about his new film: a spaghetti Western silent. To a degree, Tarantino understands the response. "There transposed to the antebellum South that follows a slave (Jamie is no setup for Django, for what we're trying to do. -

The Dallas Symphony Orchestra Presents: Beethoven at 250

The Dallas Symphony Orchestra Presents: Beethoven at 250 January 22 and 23, 2020 Dear Fellow Educators, Ludwig van Beethoven lived a life driven by an unquenchable need to make music. On this, the 250th anniver- sary of his birth, the Dallas Symphony celebrates his legacy: music that still delights, challenges, and moves us. Consumed by a towering genius, he lived a life that was complex, inspired, unique, and difficult. But even when he was young, it was clear that he would leave a lasting impact. At the age of 17, Beethoven made his first trip to Vienna, the city that would become his home. There, he was quickly immersed in the life of Europe’s cultural capital, and played the piano for none other than Mozart. Mozart’s prediction: “You will make a big noise in the world.” At the dawn of the 19th century, the world was changing. The French Revolution had rocked Europe, Napoleon was rising to power, and every aspect of human life seemed to shift. It was an age of change in ideas, the arts, science, and the structure of society itself. Musically, Beethoven led the charge into a new century by replacing established Classical ideals with a wave of Romanticism, valuing imagination and emotion over intellect and reason. Music has never been the same since, and his many musical innovations paved the way for countless composers after him. Some of his string quartets, in fact, prompted one man to remark, “Surely you do not consider these works to be music?” Beethoven replied, “Oh, they are not for you, but for a later age.” He was right.