Health Workers' Perceived Challenges for Dengue Prevention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

21 Blue Flags for the Best Beaches in the Caribbean and Latin America

1. More than six million people arrived to the Dominican Republic in 2015 2. Dominican Republic: 21 blue flags for the best beaches in the Caribbean and Latin America 3. Dominican Republic Named Best Golf Destination in Latin America and the Caribbean 2016 4. Dominican Republic Amber Cove is the Caribbean's newest cruise port 5. Dominican Republic Hotel News Round-up 6. Aman Resorts with Amanera, Dominican Republic 7. Hard Rock International announces Hard Rock Hotel & Casino Santo Domingo 8. New Destination Juan Dolio, Emotions By Hodelpa & Sensations 9. New flight connections to the Dominican Republic 10. Towards the Caribbean sun with Edelweiss 11. Whale whisperer campaign wins Gold medal at the FOX awards 2015 12. Dominican Republic – the meetings and incentive paradise 13. Activities and places to visit in the Dominican Republic 14. Regions of the Dominican Republic 15. Dominican Republic Calendar of Events 2016 1. More than six million people arrived to the Dominican Republic in 2015 The proportion of Germans increased by 7.78 percent compared to 2014 Frankfurt / Berlin. ITB 2016. The diversity the Dominican Republic has to offer has become very popular: in 2015, a total of 6.1 million arrivals were recorded on this Caribbean island, of which 5.6 million were tourists – that is, 8.92 percent up on the previous year. Compared to 2014 the proportion of Germans increased by 7.78 percent in 2015. Whereas in 2014, a total of 230,318 tourists from the Federal Republic visited the Dominican Republic, in 2015 248,248 German tourists came here. Furthermore, a new record was established in November last year: compared to the same period in the previous year, 19.8 percent more German tourists visited the Caribbean island. -

Anolis Cybotes Group)

Evolution, 57(10), 2003, pp. 2383±2397 PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS OF ECOLOGICAL AND MORPHOLOGICAL DIVERSIFICATION IN HISPANIOLAN TRUNK-GROUND ANOLES (ANOLIS CYBOTES GROUP) RICHARD E. GLOR,1,2 JASON J. KOLBE,1,3 ROBERT POWELL,4,5 ALLAN LARSON,1,6 AND JONATHAN B. LOSOS1,7 1Department of Biology, Campus Box 1137, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri 63130-4899 2E-mail: [email protected] 3E-mail: [email protected] 4Department of Biology, Avila University, 11901 Wornall Road, Kansas City, Missouri 64145-1698 5E-mail: [email protected] 6E-mail: [email protected] 7E-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Anolis lizards in the Greater Antilles partition the structural microhabitats available at a given site into four to six distinct categories. Most microhabitat specialists, or ecomorphs, have evolved only once on each island, yet closely related species of the same ecomorph occur in different geographic macrohabitats across the island. The extent to which closely related species of the same ecomorph have diverged to adapt to different geographic macro- habitats is largely undocumented. On the island of Hispaniola, members of the Anolis cybotes species group belong to the trunk-ground ecomorph category. Despite evolutionary stability of their trunk-ground microhabitat, populations of the A. cybotes group have undergone an evolutionary radiation associated with geographically distinct macrohabitats. A combined phylogeographic and morphometric study of this group reveals a strong association between macrohabitat type and morphology independent of phylogeny. This association results from long-term morphological evolutionary stasis in populations associated with mesic-forest environments (A. c. cybotes and A. marcanoi) and predictable morphometric changes associated with entry into new macrohabitat types (i.e., xeric forests, high-altitude pine forest, rock outcrops). -

The Scorpion Fauna of Mona Island, Puerto Rico (Scorpiones: Buthidae, Scorpionidae)

The Scorpion Fauna of Mona Island, Puerto Rico (Scorpiones: Buthidae, Scorpionidae) Rolando Teruel, Mel J. Rivera & Alejandro J. Sánchez August 2017 – No. 250 Euscorpius Occasional Publications in Scorpiology EDITOR: Victor Fet, Marshall University, ‘[email protected]’ ASSOCIATE EDITOR: Michael E. Soleglad, ‘[email protected]’ Euscorpius is the first research publication completely devoted to scorpions (Arachnida: Scorpiones). Euscorpius takes advantage of the rapidly evolving medium of quick online publication, at the same time maintaining high research standards for the burgeoning field of scorpion science (scorpiology). Euscorpius is an expedient and viable medium for the publication of serious papers in scorpiology, including (but not limited to): systematics, evolution, ecology, biogeography, and general biology of scorpions. Review papers, descriptions of new taxa, faunistic surveys, lists of museum collections, and book reviews are welcome. Derivatio Nominis The name Euscorpius Thorell, 1876 refers to the most common genus of scorpions in the Mediterranean region and southern Europe (family Euscorpiidae). Euscorpius is located at: http://www.science.marshall.edu/fet/Euscorpius (Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia 25755-2510, USA) ICZN COMPLIANCE OF ELECTRONIC PUBLICATIONS: Electronic (“e-only”) publications are fully compliant with ICZN (International Code of Zoological Nomenclature) (i.e. for the purposes of new names and new nomenclatural acts) when properly archived and registered. All Euscorpius issues starting from No. 156 (2013) are archived in two electronic archives: • Biotaxa, http://biotaxa.org/Euscorpius (ICZN-approved and ZooBank-enabled) • Marshall Digital Scholar, http://mds.marshall.edu/euscorpius/. (This website also archives all Euscorpius issues previously published on CD-ROMs.) Between 2000 and 2013, ICZN did not accept online texts as "published work" (Article 9.8). -

Download Vol. 21, No. 1

BULLETIN of the FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM Biological Sciences Volume 21 1976 Number 1 VARIATION AND RELATIONSHIPS OF SOME HISPANIOLAN FROGS (LEPTODACTYLIDAE, ELEUTHERODACTYLUS ) OF THE RICORDI GROUP ALBERT SCHWARTZ .A-' UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA GAINESVILLE Numbers of the BULLETIN OF THE FLORIDA STATE MUSEUM, BIOLOGICAL SCIENCES, are published at irregular intervals. Volumes contain about 300 pages and are not necessarily completed in any one calendar year. CARTER R. GILBERT, Editor RHODA J. RYBAK, Managing Editor Consultant for this issue: ERNEST E. WILLIAMS Communications concerning purchase or exchange of the publications and all manu- scripts should be addressed to the Managing Editor of the Bulletin, Florida State Museum, Museum Road, University of Florida, Gainesville, Florida 32611. This public document was promulgated at an annual cost of $1647.38 or $1.647 per copy. It makes available to libraries, scholars, and all interested persons the results of researchers in the natural sciences, emphasizing the Circum-Caribbean region. Publication date: Aug. 6, 1976 Price: $1.70 VARIATION AND RELATIONSHIPS OF SOME HISPANIOLAN FROGS ( LEPTODACTYLIDAE, ELEUTHERODACTYLUS) OF THE RICORDI GROUP ALBERT SCHWARTZ1 SYNOPSIS: Five species of Hispaniolan Eleutherodactylus of the ricordi group are discussed, and variation in these species is given in detail. The relationships of these five species, both among themselves and with other Antillean members of the ricordi group, are treated, and a hypothetical sequence of inter- and intra-island trends is given, -

Octubre, 2014. No. 7 Editores Celeste Mir Museo Nacional De Historia Natural “Prof

Octubre, 2014. No. 7 Editores Celeste Mir Museo Nacional de Historia Natural “Prof. Eugenio de Jesús Marcano” [email protected] Calle César Nicolás Penson, Plaza de la Cultura Juan Pablo Duarte, Carlos Suriel Santo Domingo, 10204, República Dominicana. [email protected] www.mnhn.gov.do Comité Editorial Alexander Sánchez-Ruiz BIOECO, Cuba. [email protected] Altagracia Espinosa Instituto de Investigaciones Botánicas y Zoológicas, UASD, República Dominicana. [email protected] Ángela Guerrero Escuela de Biología, UASD, República Dominicana Antonio R. Pérez-Asso MNHNSD, República Dominicana. Investigador Asociado, [email protected] Blair Hedges Dept. of Biology, Pennsylvania State University, EE.UU. [email protected] Carlos M. Rodríguez MESCyT, República Dominicana. [email protected] César M. Mateo Escuela de Biología, UASD, República Dominicana. [email protected] Christopher C. Rimmer Vermont Center for Ecostudies, EE.UU. [email protected] Daniel E. Perez-Gelabert USNM, EE.UU. Investigador Asociado, [email protected] Esteban Gutiérrez MNHNCu, Cuba. [email protected] Giraldo Alayón García MNHNCu, Cuba. [email protected] James Parham California State University, Fullerton, EE.UU. [email protected] José A. Ottenwalder Mahatma Gandhi 254, Gazcue, Sto. Dgo. República Dominicana. [email protected] José D. Hernández Martich Escuela de Biología, UASD, República Dominicana. [email protected] Julio A. Genaro MNHNSD, República Dominicana. Investigador Asociado, [email protected] Miguel Silva Fundación Naturaleza, Ambiente y Desarrollo, República Dominicana. [email protected] Nicasio Viña Dávila BIOECO, Cuba. [email protected] Ruth Bastardo Instituto de Investigaciones Botánicas y Zoológicas, UASD, República Dominicana. [email protected] Sixto J. Incháustegui Grupo Jaragua, Inc. -

Zootaxa: a Review of the Asilid (Diptera) Fauna from Hispaniola

ZOOTAXA 1381 A review of the asilid (Diptera) fauna from Hispaniola with six genera new to the island, fifteen new species, and checklist AUBREY G. SCARBROUGH & DANIEL E. PEREZ-GELABERT Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand AUBREY G. SCARBROUGH & DANIEL E. PEREZ-GELABERT A review of the asilid (Diptera) fauna from Hispaniola with six genera new to the island, fifteen new species, and checklist (Zootaxa 1381) 91 pp.; 30 cm. 14 Dec. 2006 ISBN 978-1-86977-066-2 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-86977-067-9 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2006 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41383 Auckland 1030 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ © 2006 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. ISSN 1175-5326 (Print edition) ISSN 1175-5334 (Online edition) Zootaxa 1381: 1–91 (2006) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1381 Copyright © 2006 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A review of the asilid (Diptera) fauna from Hispaniola with six genera new to the island, fifteen new species, and checklist AUBREY G. SCARBROUGH1 & DANIEL E. PEREZ-GELABERT2 1Visiting Scholar, Department of Entomology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85741. E-mail: [email protected] 2Department of Entomology, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, P. -

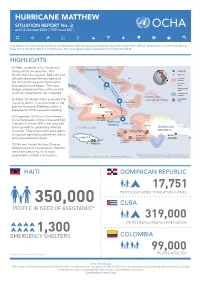

HURRICANE MATTHEW SITUATION REPORT No

HURRICANE MATTHEW SITUATION REPORT No. 2 as of 4 October 2016 (1700 hours EST) This report is produced by OCHA in collaboration with humanitarian partners and with inputs from official institutions. It covers the period from 3 to 4 October 2016 at 17:00 hours. The next report will be published on 5 October 2016. HIGHLIGHTS Forecast track and possible influence (as of 4 Oct 2016) • In Haiti, torrential rains, floods and BAHAMAS strong winds are reported. The Capital city Government has issued a Red alert and Major city officially requested the assistance of Hurricane warning the UN and its support mechanisms. 5 Oct, 2pm Hurricane Evacuations have begun. The main projected track watch Tropical storm bridge connecting Port-au-Prince with watch southern departments has collapsed. Tropical storm warning TURKS AND • Coordination In Cuba, the Government activated the CAICOS ISLANDS hubs 5 Oct, 2am “cyclonic alarm” in six provinces of the CUBA east for Hurricane Matthew, which is Holguin expected to hit the area this evening. Guantanamo • UN agencies, NGOs and the Interna- Santiago tional Federation of Red Cross and Red de Cuba Hurricane Crescent Societies (IFRC) are prepared 4 Oct, 5pm Matthew HAITI to bring relief to potentially affected Caribbean Sea DOMINICAN countries. They have mobilized experts Port-au-Prince REPUBLIC Jérémie to support national humanitarian teams (UNDAC) OCHA office Santo and pre-positioned stocks. JAMAICA MINUSTAH Domingo UNDAC Les Cayes UNDAC (UNDAC) • OCHA and United Nations Disaster Kingston Assessment and Coordination (UNDAC) teams are preparing initial rapid The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map assessments in Haiti and Jamaica. -

Works, and Natural History

INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0182 Antlions of Hispaniola (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae) Robert B. Miller Research Associate Florida State Collection of Arthropods P. O. Box 147100 Gainesville, FL, 32614-7100, U.S.A. Lionel A. Stange Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Florida State Collection of Arthropods P. O. Box 147100 Gainesville, FL, 32614-7100, U.S.A. Date of Issue: May 27, 2011 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Robert B. Miller and Lionel A. Stange Antlions of Hispaniola (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae) Insecta Mundi 0182: 1-28 Published in 2011 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. P. O. Box 141874 Gainesville, FL 32614-1874 U. S. A. http://www.centerforsystematicentomology.org/ Insecta Mundi is a journal primarily devoted to insect systematics, but articles can be published on any non-marine arthropod. Topics considered for publication include systematics, taxonomy, nomencla- ture, checklists, faunal works, and natural history. Insecta Mundi will not consider works in the applied sciences (i.e. medical entomology, pest control research, etc.), and no longer publishes book re- views or editorials. Insecta Mundi publishes original research or discoveries in an inexpensive and timely manner, distributing them free via open access on the internet on the date of publication. Insecta Mundi is referenced or abstracted by several sources including the Zoological Record, CAB Abstracts, etc. Insecta Mundi is published irregularly throughout the year, with completed manu- scripts assigned an individual number. Manuscripts must be peer reviewed prior to submission, after which they are reviewed by the editorial board to ensure quality. One author of each submitted manu- script must be a current member of the Center for Systematic Entomology. -

Antlions of Hispaniola (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae)

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Insecta Mundi Florida 5-27-2011 Antlions of Hispaniola (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae) Robert B. Miller Florida State Collection of Arthropods Lionel A. Stange Florida State Collection of Arthropods Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi Part of the Entomology Commons Miller, Robert B. and Stange, Lionel A., "Antlions of Hispaniola (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae)" (2011). Insecta Mundi. 694. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/insectamundi/694 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for Systematic Entomology, Gainesville, Florida at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Insecta Mundi by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. INSECTA MUNDI A Journal of World Insect Systematics 0182 Antlions of Hispaniola (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae) Robert B. Miller Research Associate Florida State Collection of Arthropods P. O. Box 147100 Gainesville, FL, 32614-7100, U.S.A. Lionel A. Stange Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Florida State Collection of Arthropods P. O. Box 147100 Gainesville, FL, 32614-7100, U.S.A. Date of Issue: May 27, 2011 CENTER FOR SYSTEMATIC ENTOMOLOGY, INC., Gainesville, FL Robert B. Miller and Lionel A. Stange Antlions of Hispaniola (Neuroptera: Myrmeleontidae) Insecta Mundi 0182: 1-28 Published in 2011 by Center for Systematic Entomology, Inc. P. O. Box 141874 Gainesville, FL 32614-1874 U. S. A. http://www.centerforsystematicentomology.org/ Insecta Mundi is a journal primarily devoted to insect systematics, but articles can be published on any non-marine arthropod. Topics considered for publication include systematics, taxonomy, nomencla- ture, checklists, faunal works, and natural history. -

“I Felt Like the World Was Falling Down on Me” Adolescent Girls’ Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in the Dominican Republic

HUMAN “I Felt Like the World RIGHTS Was Falling Down on Me” WATCH Adolescent Girls’ Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in the Dominican Republic “I Felt Like the World Was Falling Down on Me” Adolescent Girls’ Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in the Dominican Republic Copyright © 2019 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-6231-37403 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch defends the rights of people worldwide. We scrupulously investigate abuses, expose the facts widely, and pressure those with power to respect rights and secure justice. Human Rights Watch is an independent, international organization that works as part of a vibrant movement to uphold human dignity and advance the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Sydney, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org JUNE 2019 ISBN: 978-1-6231-37403 “I Felt Like the World Was Falling Down on Me” Adolescent Girls’ Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights in the Dominican Republic Introduction ..........................................................................................................1 Recommendations .............................................................................................. -

(CARCIP) Phase 1 (Grenada, St Vincent and the Grenadines, St

Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Regional Communications Infrastructure Program (RCIP) Phase 1 Grenada, St Vincent and the Grenadines, St. Lucia and Dominican Republic (CARCIP Phase 1) Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 1 6/18/2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………....2 1.1BRIEF BACKGROUND…………………………………………………………………………2 1.2 THE ESMF REPORT…………………………………………………………………………3 1.3 SCOPE OF WORK…………………………………………………………………………….3 2.0 DESCRIPTION OF PROPOSED PROJECT……………………………………………5 2.1 Overview……………………………………………………………………………………5 2.2 Activities with potential Natural and Human Environmental Impacts………….7 3.0 DESCRIPTION OF ENVIRONMENT……………………………………………………7 3.1 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………….7 3.2 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT……………………………………………………………………7 3.2.1 Location and Size………………………………………………………………………7 3.2.2. Geology………………………………………………………………………………….8 3.2.3 Soil………………………………………………………………………………………..9 3.2.4 Topography and Drainage………………………………………………...10 3.2.5 Climate…………………………………………………………………………………..10 3.2.6 BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT………………………………………………………………11 3.2.6.1 Flora and Fauna……………………………………………………………………11 3.2.7 SOCIO-CULTURAL ENVIRONMENT……………………………………………………….12 3.2.7.1 Population…………………………………………………………………………..12 3.2.7.2 Land use…………………………………………………………………………….13 3.2.7.3 Source of Livelihood……………………………………………………………… 13 3.2.7.4 Community Structure……………………………………………………………….14 3.2.7.5 Cultural Priorities ……………………………………………………………………14 3.2.7.6 Vulnerable -

Lex Mundi in Latin America and the Caribbean Key Market Developments 2019 About Lex Mundi

Lex Mundi in Latin America and the Caribbean Key Market Developments 2019 About Lex Mundi Lex Mundi, the world’s leading network of independent law firms, brings together the collaboration, knowledge and resources of 160 rigorously vetted, top-tier law firms in 100+ countries. Supported by client-focused methodologies, innovative technology, joint learning and training, member law firms collaborate seamlessly across borders, industries and markets to help clients manage complex cross-border legal risks, issues and opportunities. Through the Lex Mundi global service platform, member firms can deliver integrated and efficient solutions focused on real business results for clients. Lex Mundi member firms are among the most experienced and knowledgeable in the world. Recognized as leaders in their local markets, they have a comprehensive understanding of the culture, politics, government, law and history of their respective markets, and have strong connections to local decision- makers. Admittance is granted only to firms that meet rigorous selection criteria and maintaining membership requires a review every six years. Lex Mundi member firms work together fluidly and efficiently across borders, often in tight time frames. When the call comes in, they can mobilize cross-border teams with the combined local perspectives needed to quickly interpret your opportunities and challenges. Lex Mundi is World Ready, providing the insight, innovation, resources and cross-border collaboration you need to meet the challenges of doing business in virtually any market, virtually anywhere in the world. Lex Mundi – the law firms that know your markets. Find out more about Lex Mundi at: www.lexmundi.com 2 © Copyright 2019 Lex Mundi Lex Mundi in Latin America and the Caribbean Key Market Developments 2019 About This Publication This guide details the market outlook and key business and legal developments across jurisdictions in Latin America and the Caribbean.