1 Enhanced Health Facility Surveys to Support Malaria Control and Elimination Across Different

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mangrove Mapping for the Verde Island Passage

MANGROVE MAPPING FOR THE VERDE ISLAND PASSAGE This publication was prepared by Conservation International Philippines with funding from the United States Agency for International Development’s Coral Triangle Support Partnership (CTSP) (September 2011) Cover photo: This mangrove forest is part of a Marine Protected Area in Balibago, Verde Island Passage in the Philippines. Photo: © CTSP / Tory Read Mangrove Mapping for the Verde Island Passage, Philippines November 2011 USAID Project Number GCP LWA Award # LAG-A-00-99-00048-00 For more information on the six-nation Coral Triangle Initiative, please contact: Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries, and Food Security Interim Regional Secretariat Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia Mina Bahari Building II, 17th Floor Jalan Medan Merdeka Timur No 16 Jakarta Pusat 10110 Indonesia www.thecoraltriangleintitiave.org This is a publication of the Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries, and Food Security (CTI- CFF). Funding for the preparation of this document was provided by the USAID-funded Coral Triangle Support Partnership (CTSP). CTSP is a consortium led by the World Wildlife Fund, The Nature Conservancy, and Conservation International with funding support from the United States Agency for International Development’s Regional Asia Program. © 2011 Coral Triangle Support Partnership. All rights reserved. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this report for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permission from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited wihout written permission of the copyright holders. -

2019 Annual Regional Economic Situationer

2019 ANNUAL REGIONAL ECONOMIC SITUATIONER National Economic and Development Authority MIMAROPA Region Republic of the Philippines National Economic and Development Authority MIMAROPA Region Tel (43) 288-1115 E-mail: [email protected] Fax (43) 288-1124 Website: mimaropa.neda.gov.ph ANNUAL REGIONAL ECONOMIC SITUATIONER 2019 I. Macroeconomy A. 2018 Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) Among the 17 regions of the country, MIMAROPA ranked 2nd— together with Davao Region and next to Bicol Region—in terms of growth rate. Among the major economic sectors, the Industry sector recorded the fastest growth of 11.2 percent in 2018 from 1.6 percent in 2017. This was followed by the Services sector, which grew by 9.3 percent in 2018 from 8.7 percent in 2017. The Agriculture, Hunting, Fishery and Forestry (AHFF) sector also grew, but at a slower pace at 2.6 percent in 2018 from 3.0 percent in 2017 (refer to Table 1). Table 1. Economic Performance by Sector and Subsector, MIMAROPA, 2017-2018 (at constant 2000 prices, in percent except GVA) Contribution Percent 2017 2018 GRDP Growth rate Sector/Subsector GVA GVA distribution growth (in P '000) (in P '000) 2017 2018 17-18 16-17 17-18 Agriculture, hunting, 26,733,849 27,416,774 20.24 19.12 0.5 3.0 2.6 forestry, and fishing Agriculture and 21,056,140 21,704,747 15.94 15.13 0.5 4.4 3.1 forestry Fishing 5,677,709 5,712,027 4.30 3.98 0.0 -1.9 0.6 Industry sector 42,649,103 47,445,680 32.29 33.08 3.7 1.6 11.2 Mining and 23,830,735 25,179,054 18.04 17.56 1.0 -5.5 5.7 quarrying Manufacturing 6,811,537 7,304,895 -

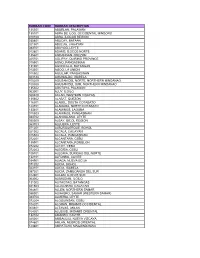

Region Penro Cenro Province Municipality Barangay

REGION PENRO CENRO PROVINCE MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY DISTRICT AREA IN HECTARES NAMEOF ORGANIZATION TYPE OF ORGANIZATION COMPONENT COMMODITY SPECIES YEAR ZONE TENURE RIVER BASIN NUMBER OF LOA WATERSHED SITECODE REMARKS MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Buenavista Sihi Lone District 34.02 LGU-Sihi LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0001-0034 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Boac Tumagabok Lone District 8.04 LGU-Tumagabok LGU Agroforestry Timber and Fruit Trees Narra, Langka, Guyabano, and Rambutan 2011 Production 11-174001-0002-0008 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 2.00 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Agroforestry Fruit Trees Langka 2011 Production 11-174001-0003-0002 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 12.01 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection Untenured 11-174001-0004-0012 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 7.04 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0005-0007 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 3.00 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0006-0003 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 1.05 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0007-0001 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Torrijos Sibuyao Lone District 2.03 LGU-Sibuyao LGU Reforestation Timber Narra 2011 Protection 11-174001-0008-0002 MIMAROPA Marinduque Boac Marinduque Buenavista Yook Lone District 30.02 LGU-Yook -

Occidental Mindoro Priority-Final2.Xlsx

Table 2. Household Population by Age Group, Sex, and City/Municipality: 2007 Age Group and City/Municipality Both Sexes Male Female OCCIDENTAL MINDORO All Ages 419,316 217,405 201,911 Under 1 10,891 5,642 5,249 1 - 4 44,654 23,279 21,375 5 - 9 56,840 29,229 27,611 10 - 14 53,828 27,862 25,966 15 - 19 42,346 22,787 19,559 20 - 24 33,335 17,491 15,844 25 - 29 31,254 16,190 15,064 30 - 34 28,168 14,700 13,468 35 - 39 26,603 13,810 12,793 40 - 44 22,288 11,664 10,624 45 - 49 18,676 9,756 8,920 50 - 54 15,038 7,792 7,246 55 - 59 11,190 5,743 5,447 60 - 64 8,455 4,158 4,297 65 - 69 6,190 3,004 3,186 70 - 74 4,549 2,140 2,409 75 - 79 2,585 1,169 1,416 80 and over 2,426 989 1,437 0-17 193,895 100,901 92,994 18 and over 225,421 116,504 108,917 ABRA DE ILOG All Ages 25,125 13,014 12,111 Under 1 823 420 403 1 - 4 3,098 1,612 1,486 5 - 9 3,537 1,810 1,727 10 - 14 3,240 1,677 1,563 15 - 19 2,334 1,237 1,097 20 - 24 1,928 986 942 25 - 29 1,913 993 920 30 - 34 1,589 848 741 35 - 39 1,584 824 760 40 - 44 1,224 652 572 45 - 49 1,093 581 512 50 - 54 823 420 403 55 - 59 587 295 292 60 - 64 503 258 245 65 - 69 354 170 184 70 - 74 243 126 117 75 - 79 141 61 80 80 and over 111 44 67 0-17 12,151 6,322 5,829 18 and over 12,974 6,692 6,282 Table 2. -

3D Critical Areas

Philippine National Bank (Europe) Plc Door to Door Listing as of 13/10/2006 AREA DELIVERY CATEGORY REGION 4-B MARINDUQUE BOAC OSA BUENAVISTA OSA GASAN OSA MOGPOG OSA STA. CRUZ OSA TORRIJOS OSA MINDORO OCCIDENTAL ABRA DE ILOG OSA CALINTAAN OSA LOOC OSA LUBANG OSA MAGSAYSAY OSA MAMBURAO OSA PALUAN OSA RIZAL OSA SABLAYAN OSA STA. CRUZ OSA MINDORO ORIENTAL BACO S CALAPAN * canubing II OSA * gutad OSA * maidlang OSA * nag iba II OSA * navotas OSA * sta cruz OSA * selonai OSA NAUJAN * malayaOSA * pagkakaisa OSA * malinao OSA PUERTO GALERA OSA * talipanan OSA * aninuan OSA * white beach OSA * san isidro OSA * minolo OSA * balatero OSA * boquete OSA * san antonio OSA * poblacion OSA * dalaruan OSA * palangan OSA * sabang OSA * sinandigan OSA * tabinay OSA Legend: OTD - Out of Town Delivery OSA - Out of Service Area NS - Non-Serviceable Philippine National Bank (Europe) Plc Door to Door Listing as of 13/10/2006 * villaflor OSA * dulangan OSA SAN TEODORO OSA GLORIA * balete OSA * langlang OSA * tinalunan OSA * bulbugan OSA * banus OSA * lucio laurel OSA PINAMALAYAN * anoling OTD * bangbang OTD * bacungan OTD * guinhawa OTD * malaya OTD * maliancog OTD * pili OTD * sta. Isabel OTD * banilad OSA * buli OSA * inclanay OSA * marayos OSA * pambisan OSA * ranzon OSA * sabang OSA * simborio OSA * upper bongol OSA * lower bongol OSA POLA OSA BANSUD OSA BONGABONG OSA BULALACAO OSA MANSALAY OSA ROXAS OSA * poblacion OSA * cantil OSA SOCORRO * leuteboro 1 & 2 OTD PALAWAN ABORLAN * sagpangan OTD * tigman OTD * cabigaan OTD * barake OTD * marikit OTD * apo-aporawan -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population

2010 Census of Population and Housing Marinduque Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population MARINDUQUE 227,828 BOAC (Capital) 52,892 Agot 502 Agumaymayan 525 Amoingon 1,346 Apitong 405 Balagasan 801 Balaring 501 Balimbing 1,489 Balogo 1,397 Bangbangalon 1,157 Bamban 443 Bantad 1,405 Bantay 1,389 Bayuti 220 Binunga 691 Boi 609 Boton 279 Buliasnin 1,281 Bunganay 1,811 Maligaya 707 Caganhao 978 Canat 621 Catubugan 649 Cawit 2,298 Daig 520 Daypay 329 Duyay 1,595 Ihatub 1,102 Isok II Pob. (Kalamias) 677 Hinapulan 672 Laylay 2,467 Lupac 1,608 Mahinhin 560 Mainit 854 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Marinduque Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Malbog 479 Malusak (Pob.) 297 Mansiwat 390 Mataas Na Bayan (Pob.) 564 Maybo 961 Mercado (Pob.) 1,454 Murallon (Pob.) 488 Ogbac 433 Pawa 732 Pili 419 Poctoy 324 Poras 1,079 Puting Buhangin 477 Puyog 876 Sabong 176 San Miguel (Pob.) 217 Santol 1,580 Sawi 1,023 Tabi 1,388 Tabigue 895 Tagwak 361 Tambunan 577 Tampus (Pob.) 1,145 Tanza 1,521 Tugos 1,413 Tumagabok 370 Tumapon 129 Isok I (Pob.) 1,236 BUENAVISTA 23,111 Bagacay 1,150 Bagtingon 1,576 Bicas-bicas 759 Caigangan 2,341 Daykitin 2,770 Libas 2,148 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and Housing Marinduque Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, -

Rurban Code Rurban Description 135301 Aborlan

RURBAN CODE RURBAN DESCRIPTION 135301 ABORLAN, PALAWAN 135101 ABRA DE ILOG, OCCIDENTAL MINDORO 010100 ABRA, ILOCOS REGION 030801 ABUCAY, BATAAN 021501 ABULUG, CAGAYAN 083701 ABUYOG, LEYTE 012801 ADAMS, ILOCOS NORTE 135601 AGDANGAN, QUEZON 025701 AGLIPAY, QUIRINO PROVINCE 015501 AGNO, PANGASINAN 131001 AGONCILLO, BATANGAS 013301 AGOO, LA UNION 015502 AGUILAR, PANGASINAN 023124 AGUINALDO, ISABELA 100200 AGUSAN DEL NORTE, NORTHERN MINDANAO 100300 AGUSAN DEL SUR, NORTHERN MINDANAO 135302 AGUTAYA, PALAWAN 063001 AJUY, ILOILO 060400 AKLAN, WESTERN VISAYAS 135602 ALABAT, QUEZON 116301 ALABEL, SOUTH COTABATO 124701 ALAMADA, NORTH COTABATO 133401 ALAMINOS, LAGUNA 015503 ALAMINOS, PANGASINAN 083702 ALANGALANG, LEYTE 050500 ALBAY, BICOL REGION 083703 ALBUERA, LEYTE 071201 ALBURQUERQUE, BOHOL 021502 ALCALA, CAGAYAN 015504 ALCALA, PANGASINAN 072201 ALCANTARA, CEBU 135901 ALCANTARA, ROMBLON 072202 ALCOY, CEBU 072203 ALEGRIA, CEBU 106701 ALEGRIA, SURIGAO DEL NORTE 132101 ALFONSO, CAVITE 034901 ALIAGA, NUEVA ECIJA 071202 ALICIA, BOHOL 023101 ALICIA, ISABELA 097301 ALICIA, ZAMBOANGA DEL SUR 012901 ALILEM, ILOCOS SUR 063002 ALIMODIAN, ILOILO 131002 ALITAGTAG, BATANGAS 021503 ALLACAPAN, CAGAYAN 084801 ALLEN, NORTHERN SAMAR 086001 ALMAGRO, SAMAR (WESTERN SAMAR) 083704 ALMERIA, LEYTE 072204 ALOGUINSAN, CEBU 104201 ALORAN, MISAMIS OCCIDENTAL 060401 ALTAVAS, AKLAN 104301 ALUBIJID, MISAMIS ORIENTAL 132102 AMADEO, CAVITE 025001 AMBAGUIO, NUEVA VIZCAYA 074601 AMLAN, NEGROS ORIENTAL 123801 AMPATUAN, MAGUINDANAO 021504 AMULUNG, CAGAYAN 086401 ANAHAWAN, SOUTHERN LEYTE -

Wash Facilities and Diarrhoea Occurrence at the Eco-Zones of Abra De Ilog, Philippines: a Comparative Assessment

ASM Sc. J., 13, Special Issue 5, 2020 for APRU2018, 13-19 WaSH Facilities and Diarrhoea Occurrence at the Eco-zones of Abra de Ilog, Philippines: A Comparative Assessment F.R.C. Paro 1∗, V.B. Molina2 , B.B. Magtibay3 , V.F. Fadrilan-Camacho2 , M.F.T. Lomboy2 and H.G.C. Agosto2 1 Department of Community and Environmental Resource Planning, College of Human Ecology, University of the Philippines Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines 4031 2 College of Public Health, University of the Philippines Manila 3 World Health Organization – Philippines Eco-zones upland, lowland and coastal areas have varying accessibility to resources like water. This variability in water sources may influence hygiene and sanitation facilities, and health outcomes like diarrheal diseases. This ecological study examined the link between the completeness of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH) facilities and diarrhea occurrence at the eco-zones of the Municipality of Abra de Ilog, Philippines. A total of 418 households served as respondents and mixed participatory methods were used. Results showed that the upland eco-zone had the highest proportion of households with diarrhea (64.0%) regardless of whether they have complete, incomplete or no WaSH facility at all, followed by coastal (34.6%) and lowland (16.2%) eco-zones. More than 60% of households with incomplete facilities drinking water and handwashing facilities only experienced diarrhea. The absence of toilet facilities increases likelihood for diarrheal disease. The presence of a complete set of WaSH facilities a potable drinking water source, improved sanitary toilet facility and hand-washing facility at each household was important to lower diarrheal disease burden. -

Of the Verde Island Passage, Philippines for More Information on the Verde Island Passage Vulnerability Assessment Project, Contact

Climate change vulnerability assessment of the Verde Island Passage, Philippines For more information on the Verde Island Passage Vulnerability Assessment Project, contact: Emily Pidgeon, PhD Director, Marine Climate Change Program Conservation International–Global Marine Division [email protected] Rowena Boquiren, PhD Socioeconomics and Policy Unit (SEPU) Leader Conservation International–Philippines [email protected] Conservation International 2011 Crystal Drive, Suite 500 Arlington, VA 22202 USA Web: www.conservation.org This document should be cited as: R. Boquiren, G. Di Carlo, and M.C. Quibilan (Eds). 2010. Climate Change Vulnerability Assessment of the Verde Island Passage, Philippines. Technical report. Conservation International, Arlington, Virginia, USA. Science Communication Team Photo credits ©CI/photo by Michelle Encomienda ©Teri Aquino ©CI/photo by Jürgen Freund Tim Carruthers and Jane Hawkey ©CI/photo by Haraldo Castro ©Leonard J McKenzie Integration & Application Network ©Tim Carruthers ©CI/photo by Miledel C. Quibilan ©Benjamin De Ridder, Marine Photobank ©rembss, Flickr University of Maryland Center for ©CI/photo by Giuseppe Di Carlo ©Badi Samaniego © Google Earth ©CI/photo by Sterling Zumbrunn Environmental Science ©Keith Ellenbogen www.ian.umces.edu ii Preface The Verde Island Passage, in the sub-national area of dependent upon them. The assessment evaluated the Luzon in the northern Philippines, is located within the vulnerability of the Verde Island Passage to climate globally significant Coral Triangle, an area considered change and determined the priority actions needed to the center of the world’s marine biodiversity. The Verde ensure that its ecosystems and coastal societies can Island Passage is a conservation corridor that spans adapt to future climate conditions. -

BALANCED-Philippines Project Overview and Year 2 Workplan October

Building Actors and Leaders for Advancing Community Excellence in Development: The BALANCED Project BALANCED-Philippines Project Overview and Year 2 Workplan October 1, 2011 – December 31, 2012 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development under the terms of Cooperative Agreement No. GPO-A-00-08-00002-00. The project is managed by the University of Rhode Island Coastal Resources Center in collaboration with PATH Foundation Philippines, Inc. and Conservational International. For more information contact: Linda Bruce, Project Director—[email protected] Ronald Quintana, Program Manager: [email protected] i Table of Contents ACRONYMS LIST ................................................................................................................ II INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 1 YEAR 2 WORKPLAN .......................................................................................................... 6 IR 1: IMPROVED ACCESS TO FP/RH SERVICES IN KEY BIOREGIONS ......................................... 6 1.1 Conduct training of trainers on PHE CBD and adult PE system ............................ 8 1.2 Recruit and train individuals to serve as CBD outlets and promote FP/PHE links .. 9 1.3 Develop or strengthen the system for supplying FP methods to CBD outlets ...... 10 1.4 Strengthen LGU, RHU staff and skills in FP/RH, PHE linkages, and CBD ......... 11 IR 2: INCREASED COMMUNITY AWARENESS -

About Occidental Mindoro

Brief description about Occidental Mindoro Status of MDG Goal 2 in Occidental Mindoro Interventions: One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) A About oCCIDENtAL MINDoRo On November 15, 1950, under Republic Act No. 505, Mindoro was divided in two (2) provinces: Oriental Mindoro and Occidental Mindoro. Profile Land area : 587, 985 ha. Population : 452, 971 Municipalities : 11 Barangays: 162 Economy : Agriculture-based Income Classification : 2nd Class VISION 2013 - 2015 Occidental Mindoro envisions to be the major food basket of the nation, a haven for sustainable tourism and home to people enjoying the full fruits of development. MISSION Enhance and sustainability of agricultural productivity Development, promotion and preservation of tourism potentials Responsible environmental management Infrastructure Development Improvement of Health services and facilities Meaningful education for all GOAL 2: Achieve Universal Primary Education Province of Occidental Mindoro Table 19. Summary of MDG 2 Indicators Millennium Population Development Magnitude Proportion Goals Total Male Female Total Male Female Goal 2. Achieve Universal Primary Education Proportion of Children aged 6- 11 years old 49,491 25,159 24,331 82.1 81.4 83.0 enrolled in elementary Proportion of Children aged 12-15 years old 19,962 9,435 10,527 54.2 49.2 59.7 enrolled in high school Proportion of Children aged 6- 15 years old 84,183 42,746 41,435 86.7 85.3 88.3 enrolled in school Literacy rate of 64,639 34,072 30,567 15-24 year-olds 93.0 93.6 92.4 Source: CBMS Census 2009 Source: DepEd-Occidental -

Lidar-Surveys-And-Flood-Mapping-Of-Mamburao-River.Pdf

Hazard Mapping of the Philippines Using LIDAR (Phil-LIDAR 1) LiDAR Surveys and Flood Mapping of Mamburao River © University of the Philippines Diliman and University of the Philippines-Los Baños 2017 Published by the UP Training Center for Applied Geodesy and Photogrammetry (TCAGP) College of Engineering University of the Philippines – Diliman Quezon City 1101 PHILIPPINES This research project is supported by the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) as part of its Grant-in-Aid Program and is to be cited as: E.C. Paringit, E.R. Abucay, (Eds.). (2017), LiDAR Surveys and Flood Mapping Report of Mamburao River. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Training Center for Applied Geodesy and Photogrammetry 201pp The text of this information may be copied and distributed for research and educational purposes with proper acknowledgement. While every care is taken to ensure the accuracy of this publication, the UP TCAGP disclaims all responsibility and all liability (including without limitation, liability in negligence) and costs which might incur as a result of the materials in this publication being inaccurate or incomplete in any way and for any reason. For questions/queries regarding this report, contact: Asst. Prof. Edwin R. Abucay Project Leader PHIL-LIDAR 1 Program University of the Philippines, Los Banos Los Banos, Philippines 4031 [email protected] Enrico C. Paringit, Dr. Eng. Program Leader, DREAM Program University of the Philippines Diliman Quezon City, Philippines 1101 E-mail: [email protected] National Library of the Philippines ISBN: 987-621-430-148-5 i Hazard Mapping of the Philippines Using LIDAR (Phil-LIDAR 1) TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents .