The Impact of Coffee Certification on the Economic Performance of Indonesian Actors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JURA Contact Details / Legal Information 44

E6/E60 Instructions for Use Table of contents Your E6 Control elements 4 Important information 6 Proper use ......................................................................................................................................................6 For your safety ...............................................................................................................................................6 1 Preparing and using for the first time 10 Setting up the machine ..............................................................................................................................10 Filling the bean container ...........................................................................................................................10 Determining the water hardness ..............................................................................................................10 First-time use .................................................................................................................................................11 Connecting milk ...........................................................................................................................................12 Connect accessory (with wireless connection) .......................................................................................13 2 Preparation 14 Espresso and coffee .....................................................................................................................................14 Two espressi and two -

Premium Ingredients for Exceptional Chocolate Drinks and Desserts

Premium ingredients for exceptional chocolate drinks and desserts 1 With over 150 years of experience crafting premium chocolate from bean to bar in Northern California, Ghirardelli® Chocolate is trusted by chefs and consumers to deliver quality and flavor. A full line of sauces, powders and chocolate, combined with 93% national brand awareness*, makes Ghirardelli the perfect choice for creating exceptional desserts, coffee drinks, milkshakes, smoothies and hot cocoa. A reputation for rich, intense flavors means consumers overwhelmingly prefer to order Ghirardelli branded products in restaurants and cafés across numerous categories. Make products your customers will crave by using Ghirardelli ingredients. Qualifying products may proudly bear the Ghirardelli name with our “Made With Ghirardelli” program. Source: Relevation Research, January 2011 *Ipsos Chocolate Consumer Monitor, 1001 Consumers, January 2010 Sauces An incredibly versatile product, Ghirardelli sauces add rich and intense flavors when used as an ingredient or topping. With a wide range of package sizes and flavors they are perfect for: • Coffee Drinks • Milkshakes • Ice Cream/Yogurt Toppings • Cocktails • Dessert Toppings An industry standard for specialty coffee, Ghirardelli’s sauces are preferred over competitor brands when tasted in a mocha. A higher cocoa content vs. competitor products, and the addition of Ghirardelli chocolate liquor, makes Ghirardelli’s chocolate sauce thicker with a richer, true chocolate flavor. It’s the perfect topping for desserts or beverages as well as the ideal product for decorating glassware and plates. Available sizes: Large pump bottles, squeeze bottles. Flavors include: Black Label Chocolate, Sweet Ground Chocolate, Caramel and White Chocolate. 3 Sweet Ground Chocolate For over 150 years consumers and chefs have used Ghirardelli Sweet Ground Chocolate to create decadent hot cocoa, coffee drinks and baked goods. -

Ethiopian Affogato

Ethiopian affogato On trips to Ethiopia one of my favourite things by far has been Ethiopian coffee, made in homes and cafes from freshly roasted and ground beans and served quite strong in small cups with sugar, and if you're lucky, a sprig of rue. Sometimes spices such as clove, cinnamon and cardamom are thrown in with the roasting beans for a delicately spiced version. Espresso drinks are also very popular in cities, especially macchiato (with incredible 'macchiato art' of which any London barista would be envious). Italian influence in Ethiopia is also visible in some areas in the food and architecture. I put all these things together to come up with this recipe for an Ethiopian themed Secret Kitchen dinner. Remember to freeze the bowl of your ice cream maker in advance if you have that sort! Serves: 12 small portions, or 6 for greedy people like me For the ice cream: For the coffee: 375ml whole milk coffee beans, green or roasted 375ml double cream about 6 cloves 150g sugar a small piece of cinnamon bark a pinch of salt sugar to taste about 6 green cardamom pods half a vanilla pod, or ¼ tsp vanilla extract a lemon 6 large egg yolks 1. Place milk, double cream, sugar and salt in a saucepan. Crack open the cardamom pods to reveal their black seeds and add them to the pot. Split open the vanilla, scrape out the seeds and add both pod and seeds to the pot. Zest about a quarter of the lemon into the pot. Stir to combine and heat until on the verge of simmering. -

Download Full Menu Here

RISTRETTO COFFEE LOUNGE & WINE BAR Please see Barista & order at the Bar Breakfast & Lunch Afternoon & Evening Served all day Charcuterie Board $9.00/person. Whidbey Island Bagel or Wrap Assortment of cheese, salami, olives, almonds, crackers Egg, meat, cheese, and sauce: $8.50 Brie with crackers $7.75 The Works: $9.50 Honey drizzle & almonds, or Includes Tomato, Spinach & Sun-dried Tomatoes Cranberry & almonds Bagels: Plain, Multigrain, Everything, Garlic Parmesan, Pesto Parmesan. Grilled Panini $11.50 Tortilla Wraps: Tomato or Spinach tortilla (Served with chips, Add salad for $2) Egg + Turkey Pesto Turkey, pesto mayo, havarti, spinach and Choice of sauce: Pesto mayo or Dijon mayo tomato on herbed focaccia bread Choice of cheese: Havarti or cheddar Veggie Pesto mayo, Havarti, Sun dried tomatoes, tomato Choice of meat: Bacon or sausage and spinach Vegetarian option: Spinach and tomato instead of meat. BLT Bacon, pesto mayo, tomato, sun dried tomatoes and lettuce. WIBF Bagel with Cream Cheese or Butter $4.25 Turkey Bacon Turkey, bacon, pesto mayo, havarti, Choice of bagel: Plain, Multigrain, Everything, Garlic tomato and spinach Parmesan, Pesto Parmesan, Cinnamon Raisin. Grilled Cheese Cheddar, Havarti, pesto mayo, and feta cheese Oatmeal $5.75 A large bowl of steeped oatmeal, dried cranberries, Half Panini & Salad $10.00 almonds and muscovado sugar Cold Wraps $10.00 Toast with Butter & Jam $3.95 Choice of tomato or spinach tortilla (Served with chips. Add salad for $2) Granola with Yogurt $5.25 Turkey Cranberry Turkey, cranberry, cream cheese, Vanilla yogurt topped generously with granola & dried mixed greens Chicken Caesar cranberries. Non-dairy milk available Chicken, parmesan, Cesar dressing, mixed greens and croutons Spicy Italian Salami, parmesan, pepperoncini, Italian Local Baked Goods Available Daily dressing, mixed greens and croutons Chicken Havarti Chicken, Havarti, Dijon mayo, tomatoes Sweet & Savory options available. -

THE IMPACT of COFFEE PRODUCTION on the ECONOMY of COLOMBIA By

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Senior Theses Honors College 5-5-2017 The mpI act of Coffee rP oduction on the Economy of Colombia Luke Alexander Ferguson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses Part of the International Business Commons Recommended Citation Ferguson, Luke Alexander, "The mpI act of Coffee Production on the Economy of Colombia" (2017). Senior Theses. 153. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/153 This Thesis is brought to you by the Honors College at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE IMPACT OF COFFEE PRODUCTION ON THE ECONOMY OF COLOMBIA By Luke Alexander Ferguson Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation with Honors from the South Carolina Honors College May 2017 Approved: Dr. Robert Gozalez Director of Thesis Dr. Hildy Teegen Second Reader Steve Lynn, Dean For South Carolina Honors College FERGUSON: THE IMPACT OF COFFEE IN COLOMBIA 2 I. ABSTRACT This senior thesis seeks to determine the impact that the level of coffee production in Colombia has on economic wellbeing in the country. As a proxy for economic wellbeing in different arenas, I look at the income, health, and education variables of GDP, infant mortality rate, and secondary education enrollment. I use a Two-Stage Least Squares regression model to estimate this impact, with lagged international coffee prices and the occurrence of the fungal plant disease coffee leaf rust as instruments to account for endogeneity. The data which I use in this project include country-level indicators from the World Bank and monthly coffee production quantities from Colombia’s National Federation of Coffee Growers. -

The Barista Express™ Instruction Book - BES870 IMPORTANT Contents SAFEGUARDS

the Barista Express™ Instruction Book - BES870 IMPORTANT Contents SAFEGUARDS 2 Breville Recommends Safety First READ ALL 7 Components INSTRUCTIONS BEFORE 9 Functions USE AND SAVE FOR 22 Care & Cleaning FUTURE REFERENCE 29 Troubleshooting 33 Coffees to try • Carefully read all instructions before operating and save for BREVILLE future reference. RECOMMENDS • Remove safely discard SAFETY FIRST any packaging material At Breville we are very safety and promotional labels or conscious. We design and stickers before using the manufacture consumer Barista Express™ for the products with the safety of you, first time. our valued customer, foremost in mind. In addition we ask • To eliminate a choking that you exercise a degree of hazard for young children, care when using any electrical remove and safely discard appliance and adhere to the the protective cover fitted following precautions. to the power plug of this appliance. • Do not place the Barista Express™ near the edge of a bench or table during operation. Ensure the surface is level, clean and free of water and other substances. 2 • Do not use the Barista • Do not operate the Express™ on a sink drain grinder without the board. hopper lid in position. • Do not place the Barista Keep fingers, hands, hair, Express™ on or near a hot clothing and utensils away gas or electric burner, or from the hopper during where it could touch a operation. heated oven. • Use only cold, tap water in • Do not use the Barista the water tank. Do no use Express™ inside a cabinet. any other liquid. • Always ensure the Barista • Never use the Barista Express™ is properly Express™ without water in assembled before the water tank. -

Taste, Value, and Power in the Third Wave Coffee Market

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Fischer, Edward F. Working Paper Quality and inequality: Taste, value, and power in the third wave coffee market MPIfG Discussion Paper, No. 17/4 Provided in Cooperation with: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies (MPIfG), Cologne Suggested Citation: Fischer, Edward F. (2017) : Quality and inequality: Taste, value, and power in the third wave coffee market, MPIfG Discussion Paper, No. 17/4, Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies, Cologne, http://hdl.handle.net/11858/00-001M-0000-002C-AA63-2 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/156227 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. www.econstor.eu MPIfG Discussion Paper 17/4 Quality and Inequality Taste, Value, and Power in the Third Wave Coffee Market Edward F. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2018 Contents Company Officers Group Structure Directors’ Single Report on Operations LAVAZZA GROUP — CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AT 31 DECEMBER 2018 Accounting Statements • Consolidated Statement of Financial Position • Consolidated Statement of Profit or Loss • Consolidated Statement of Comprehensive Income • Consolidated Statement of Cash Flows • Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity Notes to the Consolidated Financial Statements Independent Auditors’ Report LUIGI LAVAZZA S.P.A. — FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AT 31 DECEMBER 2018 Accounting Statements • Balance Sheet • Statement of Profit or Loss • Statement of Cash Flows Notes to the Financial Statements Statutory Auditors’ Report Independent Auditors’ Report ABSTRACT 2018 Company Officers - Group Structure Annual Report 2018 Company Officers Group Structure Board of Directors LUIGI LAVAZZA S.p.A. Chairman Alberto Lavazza Vice Chairmen Giuseppe Lavazza LAVAZZA LAVAZZA OTHER BRANDS OTHER SERVICE Marco Lavazza PROFESSIONAL SUBSIDIARIES SUBSIDIARIES SUBSIDIARIES COMPANIES SUBSIDIARIES Chief Executive Officer 100% 97% 80% 100% 99% Antonio Baravalle LAVAZZA PROFESSIONAL NIMS S.p.A. KICKING HORSE LAVAZZA TRADING COFINCAF S.p.A. HOLDING EUROPE S.r.l. COFFEE Co. Ltd SHENZHEN Co. Ltd Directors 100% 93% 100% 100% 100% Antonella Lavazza LAVAZZA PROFESSIONAL LAVAZZA PREMIUM CARTE NOIRE LAVAZZA SPAGNA LAVAZZA CAPITAL S.r.l. (UK) Ltd COFFEES Corp. S.a.s. S.L. Contents Francesca Lavazza Manuela Lavazza 100% 100% 100% 100% Pietro Boroli LAVAZZA PROFESSIONAL LPCC Canadian CARTE NOIRE OPERATIONS LAVAZZA MAROC IMMOBILIARE I.N.N.E.T. S.r.l. FRANCE S.a.s Branch S.a.s. S.a.r.l. Gabriele Galateri di Genola Company Officers and Group Structure Robert Kunze-Concewitz 100% 100% 100% 99.9% Antonio Marcegaglia LAVAZZA PROFESSIONAL LAVAZZA DEUTSCHLAND MERRILD KAFFE LEA Directors’ Single Report on Operations GERMANY G.m.b.H . -

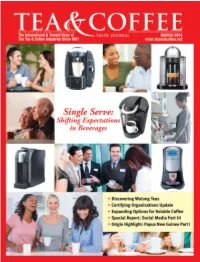

Single Serve Single Serve: Shifting Expectations in Beverages

single serve Single Serve: Shifting Expectations in Beverages 24 TEA & COFFEE TRADE JOURNAL | www.teaandcoffee.net COVER STORY Single serve has experienced an influx of innovations from the recent launch of Nespresso VertuoLine’s sys- tem to the projected release of Keurig’s 2.0 bar code system. With the continued interest of major brands, including Krispy Kreme, Lavazza, Starbucks, Bigelow and Coca-Cola, there is no telling where the world of single serve will take us. By Anne-Marie Hardie f there’s one segment in beverage that is continually their brand. “But consumers forced their hand by demand- evolving, it is single serve. Once reserved for the office ing their favorite brands in single-serve formats.” Icoffee segment, single-serve systems can now also be Before launching into single serve, John W. Rogers, vice found in hotels and of course, in homes. The Mintel Group president, Rogers Family Coffee, Lincoln, Calif., said the US, New York, reported that single serve continues to be company wanted to ensure that their product met three key the largest growing hot beverage segment—since 2011 aspects of the Rogers brand: quality, value and commitment there has been a 213 percent increase in the purchase of to the environment. Based on demand, Rogers decided to single-serve products. enter the single-serve market with a K-cup compatible “To understand why the growth is taking place, you product in 2011. have to look at the behavioral aspects. A new generation of Their initial single-cup offering used a fabric mesh filter coffee drinkers has grown up dragging their backpacks and instead of the standard plastic brewing chamber. -

Coffee Pleasure with JURA Machines It’S All About Espresso Contents the Humble Cup of Coffee Has Evolved Into a Whole Range of Modern Drinks

Coffee Pleasure With JURA Machines It’s all about Espresso Contents The humble cup of coffee has evolved into a whole range of modern drinks. The aromatic espresso Chapter 1 | The perfect espresso – The four contributing factors - PAGE | 4 remains ever-popular, but coffee’s horizons are expanding. Combinations with hot milk and soft, light- The water as-air milk foam create the latest in creative coffee beverages such as a latte macchiato, flat white or The coffee beans Cortado. The machine This brochure will illustrate that achieving the perfect coffee is about more than just the coffee beans, The individual with a whole range of other factors affecting what ultimately ends up in the cup. JURA coffee machines prepare perfect speciality coffees at the touch of a button. The barista tips in this brochure are designed Chapter 2 | Fundamental Swiss Values - PAGE | 10 to inspire you with all kinds of different ideas for preparing and serving these beverages. Innovation, Precision, Quality, Reliability, Sustainability and Service Chapter 3 | Barista tips - PAGE | 12 The perfect milk foam Coffee perishability The secret of a perfect crema Maintenance of your automatic speciality coffee machine Serving suggestions Chapter 4 | Latte art - PAGE | 16 Creative decorations Ornament Leaves Chapter 5 | Coffee recipes – JURA classics - PAGE | 20 Ristretto Espresso Macchiato Cortado Espresso doppio Café crème Caffè Latte Cappuccino Flat White Latte macchiato PAGE | 2 PAGE | 3 In this chapter 1.1 The water 1 What factors affect the perfect espresso? Water makes up 98 % of an espresso, so it is crucial to the quality of the finished product. -

Amateur's Guide to Brewing Barista Quality Coffee At

Text Copyright © Edmond Hui All rights reserved. No part of this guide may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Legal & Disclaimer The information contained in this book and its contents is not designed to replace or take the place of any form of medical or professional advice and is not meant to replace the need for independent medical, financial, legal or other professional advice or services, as may be required. The content and information in this book has been provided for educational and entertainment purposes only. The content and information contained in this book has been compiled from sources deemed reliable, and is accurate to the best of the Author's knowledge, information and belief. However, the Author cannot guarantee its accuracy and validity and cannot be held liable for any errors and/or omissions. Further changes are periodically made to this book as and when needed. Where appropriate and/or necessary, you must consult a professional (including but not limited to your doctor, attorney, financial advisor or such other professional advisor) before using any of the suggested remedies, techniques, or information in this book. Upon using the contents and information contained in this book, you agree not to hold the Author liable for any damages, costs, and expenses, including any legal fees, potentially resulting from the application of any of the information provided by this book. This disclaimer applies to any loss, damages or injury caused by the use and application, whether directly or indirectly, of any advice or information presented, whether for breach of contract, tort, negligence, personal injury, criminal intent, or under any other cause of action. -

Adaptation Strategies of Italian Cafes in Copenhagen

ADAPTATION STRATEGIES OF ITALIAN CAFES IN COPENHAGEN Master Thesis Marta Mapelli MSocSc Organisational Entrepreneurship and Innovation 15 May 2017 Supervisor: Ida Lunde Jørgensen STU: 160.828 Copenhagen Business School ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the level of authenticity of the Danes expectations around Italian coffee. A second goal is the understanding the role of managers as the motor of organisational change, and the strategies used to adapt to the customer expectations. These strategies vary in different Italian cafés, and are described as isomorphic, decoupling or loose coupling choices. A third goal was to provide a categorization of the level of authenticity of four Italian cafés in Copenhagen, and Italy, following the real-fake matrix proposed by (Gilmore & Pine, 2007). The analysis has been pursued through field research, investigating small Italian cafés in Copenhagen. Two Italian café managers have been interviewed, as well as one Italian coffee supplier. Eight coffee consumers have provided the sample to analyze the type of expectations around Italian coffee. Observations have provided additional data that helped the author to categorize four Italian cafés and their level of real or fakeness. As result, this thesis has highlighted the presence of 3 groups of customers. The unrefined consumers base their expectations around black coffee. They show preference for coffee chains and cannot describe the sensory experience around the coffee consumption. They have low standards and cannot recognize the coffee quality. The second group of customers, who has experienced Italian coffee in Italy, present a more refined taste. They are able to describe the differences among coffee products, however they do not consume nor expect to find Italian coffee in Copenahgen.