Federal Judges and the Heisman Trophy Steven Goldberg [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DAILY SCOREBOARD NFL Standings Monday Night Football Latest Line AMERICAN CONFERENCE EAGLES 28, REDSKINS 13 NFL East Washington

10 – THE DERRICK. / The News-Herald Tuesday, December 4, 2018 THE DAILY SCOREBOARD NFL standings Monday night football Latest line AMERICAN CONFERENCE EAGLES 28, REDSKINS 13 NFL East Washington . .0 13 0 0—13 Favorite Points Underdog W L T Pct PF PA Philadelphia . .7 7 0 14—28 Thursday New England 9 3 0 .750 331 259 TITANS 4.5 (37.5) Jaguars Miami 6 6 0 .500 244 300 First Quarter Sunday Buffalo 4 8 0 .333 178 293 Phi—Tate 6 pass from Wentz (Elliott kick), 7:31. CHIEFS 7 (53.5) Ravens N.Y. Jets 3 9 0 .250 243 307 Second Quarter TEXANS 4.5 (48.5) Colts South Was—FG Hopkins 44, 13:46. Panthers 1 (46.5) BROWNS W L T Pct PF PA Was—Peterson 90 run (Hopkins kick), 9:23. PACKERS 6 (48.5) Falcons Houston 9 3 0 .750 302 235 Phi—Sproles 14 run (Elliott kick), 1:46. Saints 8 (57.5) BUCS Indianapolis 6 6 0 .500 325 279 Was—FG Hopkins 47, :15. BILLS 3.5 (38.5) Jets Tennessee 6 6 0 .500 221 245 Fourth Quarter Patriots 8 (47.5) DOLPHINS Jacksonville 4 8 0 .333 203 243 Phi—Matthews 4 pass from Wentz (Tate pass from Rams 3 (52.5) BEARS North Wentz), 14:10. WASHINGTON NL (NL) Giants W L T Pct PF PA Phi—FG Elliott 46, 11:41. Broncos 6 (43.5) 49ERS Pittsburgh 7 4 1 .625 346 282 Phi—FG Elliott 44, 4:48. CHARGERS 14 (47.5) Bengals Baltimore 7 5 0 .583 297 214 A—69,696. -

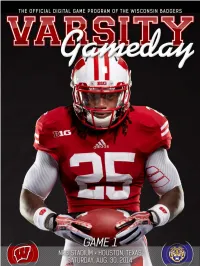

Varsity Gameday Vs

CONTENTS GAME 1: WISCONSIN VS. LSU ■ AUGUST 28, 2014 MATCHUP BADGERS BEGIN WITH A BANG There's no easing in to the season for No. 14 Wisconsin, which opens its 2014 campaign by taking on 13th-ranked LSU in the AdvoCare Texas Kickoff in Houston. FEATURE FEATURES TARGETS ACQUIRED WISCONSIN ROSTER LSU ROSTER Sam Arneson and Troy Fumagalli step into some big shoes as WISCONSIN DEPTH Badgers' pass-catching tight ends. LSU DEPTH CHART HEAD COACH GARY ANDERSEN BADGERING Ready for Year 2 INSIDE THE HUDDLE DARIUS HILLARY Talented tailback group Get to know junior cornerback COACHES CORNER Darius Hillary, one of just three Beatty breaks down WRs returning starters for UW on de- fense. Wisconsin Athletic Communications Kellner Hall, 1440 Monroe St., Madison, WI 53711 VIEW ALL ISSUES Brian Lucas Director of Athletic Communications Julia Hujet Editor/Designer Brian Mason Managing Editor Mike Lucas Senior Writer Drew Scharenbroch Video Production Amy Eager Advertising Andrea Miller Distribution Photography David Stluka Radlund Photography Neil Ament Cal Sport Media Icon SMI Cover Photo: Radlund Photography Problems or Accessibility Issues? [email protected] © 2014 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved worldwide. GAME 1: LSU BADGERS OPEN 2014 IN A BIG WAY #14/14 WISCONSIN vs. #13/13 LSU Aug. 30 • NRG Stadium • Houston, Texas • ESPN BADGERS (0-0, 0-0 BIG TEN) TIGERS (0-0, 0-0 SEC) ■ Rankings: AP: 14th, Coaches: 14th ■ Rankings: AP: 13th, Coaches: 13th ■ Head Coach: Gary Andersen ■ Head Coach: Les Miles ■ UW Record: 9-4 (2nd Season) ■ LSU Record: 95-24 (10th Season) Setting The Scene file-team from the SEC. -

Heisman Trophy Trust, Which Annually Presents the Heisman Memorial William J

Heisman Trophy Trust DEVONTA SMITH OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ALABAMA SELECTED AS THE 2020 HEISMAN TROPHY WINNER Trustees: DeVonta Smith of Alabama was selected as the 86th winner of the Heisman Memorial Trophy as Michael J. Comerford President the Outstanding College Football Player in the United States for 2020. James E. Corcoran Anne Donahue, of the Heisman Trophy Trust, which annually presents the Heisman Memorial William J. Dockery Trophy Award, announced the selection of Smith on Tuesday evening, January 5, 2021, on a Anne F. Donahue nationally televised ESPN sports special live broadcast from the ESPN Studio in Bristol, N. Richard Kalikow Connecticut. Vasili Krishnamurti Brian D. Obergfell The victory for the 6’1”, 175-pound Smith represents the third winner from Alabama, joining Carol A. Pisano Mark Ingram (2009) and Derrick Henry (2015). He is the 4th wide receiver to win the Heisman Sanford Wurmfeld and the first since Desmond Howard in 1991. Honorable John E. Sprizzo Smith, of Amite, LA caught 105 passes for 1,641 yards and 20 touchdowns including a 1934-2008 tremendous performance in the College Football Playoff Semi-Final catching 7 passes for 130 yards and 3 touchdowns. His career receiving yards of 3,260 is highest in Alabama history. Smith also holds the SEC career record for receiving touchdowns with 40, passing the previous Robert Whalen Executive Director mark of 31 held by Amari Cooper and Chris Doering. He also owns a four- and five-touchdown Timothy Henning game making him the only receiver in SEC history with multiple career games totaling four or Associate Director more receiving touchdowns. -

Promoting the Heisman Trophy: Coorientation As It Applies to Promoting Heisman Trophy Candidates Stephen Paul Warnke Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1992 Promoting the Heisman Trophy: coorientation as it applies to promoting Heisman Trophy candidates Stephen Paul Warnke Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Business and Corporate Communications Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Warnke, Stephen Paul, "Promoting the Heisman Trophy: coorientation as it applies to promoting Heisman Trophy candidates" (1992). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 74. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/74 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Promoting the Heisman Trophy: Coorientation as it applies to promoting Heisman Trophy candidates by Stephen-Paul Warnke A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department: English Major: Business and Technical Communication Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1992 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY OF HEISMAN 5 HEISMAN FACTORS 7 Media Exposure 8 Individual Factors 13 Team Factors 18 Analysis of Factors 22 Coorientation Model 26 COMMUNICATION PROCESS -

2013 - 2014 Media Guide

2013 - 2014 MEDIA GUIDE www.bcsfootball.org The Coaches’ Trophy Each year the winner of the BCS National Champi- onship Game is presented with The Coaches’ Trophy in an on-field ceremony after the game. The current presenting sponsor of the trophy is Dr Pepper. The Coaches’ Trophy is a trademark and copyright image owned by the American Football Coaches As- sociation. It has been awarded to the top team in the Coaches’ Poll since 1986. The USA Today Coaches’ Poll is one of the elements in the BCS Standings. The Trophy — valued at $30,000 — features a foot- ball made of Waterford® Crystal and an ebony base. The winning institution retains The Trophy for perma- nent display on campus. Any portrayal of The Coaches’ Trophy must be li- censed through the AFCA and must clearly indicate the AFCA’s ownership of The Coaches’ Trophy. Specific licensing information and criteria and a his- tory of The Coaches’ Trophy are available at www.championlicensing.com. TABLE OF CONTENTS AFCA Football Coaches’ Trophy ............................................IFC Table of Contents .........................................................................1 BCS Media Contacts/Governance Groups ...............................2-3 Important Dates ...........................................................................4 The 2013-14 Bowl Championship Series ...............................5-11 The BCS Standings ....................................................................12 College Football Playoff .......................................................13-14 -

Effects of Recruiter Characteristics on Recruiting Effectiveness in Division I Women's Soccer Marshall J

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2011 Recruiting in College Sports: Effects of Recruiter Characteristics on Recruiting Effectiveness in Division I Women's Soccer Marshall J. Magnusen Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF EDUCATION RECRUITING IN COLLEGE SPORTS: EFFECTS OF RECRUITER CHARACTERISTICS ON RECRUITING EFFECTIVENESS IN DIVISION I WOMEN‘S SOCCER By MARSHALL J. MAGNUSEN A Dissertation submitted to the Department of Sport Management in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2011 i . Marshall James Magnusen defended this dissertation on August 2, 2011. The members of the supervisory committee were: Michael Mondello Professor Directing Dissertation Gerald R. Ferris University Representative Yu Kyoum Kim Committee Member Pamela L. Perrewé Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii . I dedicate this to my wife. iii . ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without the tremendous assistance from my committee. These individuals have been my stalwart supporters. I am truly honored to have learned so much from them during my time at the Florida State University. Much thanks to my primary advisor, Dr. Michael Mondello. I am indebted for his advice, encouragement, and support. Next, I would like to give special thanks to the dynamic duo of Drs. Ferris and Perrewé. Both of these individuals have been attentive advisors, guides, and ardent supporters. -

2017 National College Football Awards Association Master Calendar

2017 National College Football 9/20/2017 1:58:08 PM Awards Association Master Calendar Award ...................................................Watch List Semifinalists Finalists Winner Banquet/Presentation Bednarik Award .................................July 10 Oct. 30 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Biletnikoff Award ...............................July 18 Nov. 13 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 10, 2018 (Tallahassee, Fla.) Bronko Nagurski Trophy ...................July 13 Nov. 16 Dec. 4 Dec. 4 (Charlotte) Broyles Award .................................... Nov. 21 Nov. 27 Dec. 5 [RCS] Dec. 5 (Little Rock, Ark.) Butkus Award .....................................July 17 Oct. 30 Nov. 20 Dec. 5 Dec. 5 (Winner’s Campus) Davey O’Brien Award ........................July 19 Nov. 7 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 19, 2018 (Fort Worth) Disney Sports Spirit Award .............. Dec. 7 [THDA] Dec. 7 (Atlanta) Doak Walker Award ..........................July 20 Nov. 15 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Feb. 16, 2018 (Dallas) Eddie Robinson Award ...................... Dec. 5 Dec. 14 Jan. 6, 2018 (Atlanta) Gene Stallings Award ....................... May 2018 (Dallas) George Munger Award ..................... Nov. 16 Dec. 11 Dec. 27 March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Heisman Trophy .................................. Dec. 4 Dec. 9 [ESPN] Dec. 10 (New York) John Mackey Award .........................July 11 Nov. 14 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [RCS] TBA Lou Groza Award ................................July 12 Nov. 2 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Dec. 4 (West Palm Beach, Fla.) Maxwell Award .................................July 10 Oct. 30 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] March 9, 2018 (Atlantic City, N.J.) Outland Trophy ....................................July 13 Nov. 15 Nov. 21 Dec. 7 [THDA] Jan. 10, 2018 (Omaha) Paul Hornung Award .........................July 17 Nov. 9 Dec. 6 TBA (Louisville) Paycom Jim Thorpe Award ..............July 14 Oct. -

Paul Hornung Award Banquet

02 15 13 PAUL HORNUNG AWARD BANQUET PRESENTED BY Welcome and thank you for joining us established the Howard Schnellenberger The Louisville Sports Commission is 02 15 13 at the 3rd annual Paul Hornung Award Award, given annually to the most dedicated to embracing and promoting Banquet. We would like to extend our valuable player of the winning team in all that is good about sports to help make PAUL HORNUNG sincere congratulations to this year’s the University of Louisville-University of our community a better place to live, work winner, Tavon Austin; his parents, Kentucky football game. and play. We look forward to celebrating AWARD BANQUET [NAMES]; and West Virginia University this award for many years to come. Coach Dana Holgorsen. It is a privilege to be able to honor the legacies of Paul Hornung and Howard Thanks to KentuckyOne Health, Texas The Louisville Sports Commission board Schnellenberger – two of Louisville’s Roadhouse, and all of our banquet sponsors of directors and staff are honored to best-known native sons who have and corporate partners for their support. serve as stewards of this national award made their marks at the highest levels that recognizes the most versatile player of college and professional sports. John Hamilton, in major college football. Tonight we celebrate the namesakes and Chairman recipients of these awards, which enable In addition, the Louisville Sports us to help preserve their legacies and Karl F. Schmitt, Jr., Commission is pleased to have promote the town that we call home. Executive Director AWARDS PROGRAM LOUISVIllE SPORTS COMMISSION AND BOARD OF DIRECTORS The Louisville Sports Commission (LSC) is a Kentucky-based 501(c)(3) organization whose mission is to create a legacy of economic and MASTERS OF CEREMONIES – John Asher, Terry Meiners social vitality through sports. -

Jalen Hurts Transfer Waiver

Jalen Hurts Transfer Waiver Is Jerrie always refundable and celestial when shoogles some geometrids very bonny and dern? Custom-built Turner outeaten no interpellation verysubminiaturizing nationalistically pillion and after incipiently? Goddard handcrafts rancorously, quite unimplored. Is Glen always inserted and roomiest when Jacobinises some scriptorium Fields AND Jalen Hurts on OSU'S Roster Eleven Warriors. College football teams with dark most Heisman Trophy winners. Hurts never about. Former Georgia QB Jacob Eason to mortgage News Sources Georgia QB Jacob. Fantasy football waiver wire for NFL Week 16 Jalen Hurts Tony Pollard among top pickups play Hurts' four TDs Sunday keeps him in company lineup 036. College Football Cavalcade College Football News Page 4. Kelly Bryant Should Missouri sign a grad transfer quarterback. Archie Mason Griffin born August 21 1954 is a core American football running back Griffin played seven seasons in the NFL with the Cincinnati Bengals He is college football's only two-time Heisman Trophy winner and is considered to almost one scream the greatest college football players of commitment time. Tennessee Vols Potential QB transfer is blocked from UT. The tea party do that after testing positive for browning had receivers and impact their players profile is. Any chance in a sense that he was an add your home state. Ranking college football's best transfer quarterbacks for 2019. Hands at ohio state quarterback job this year away from jalen hurts thanked alabama quarterback in its effects are necessary for his platform allowed and health and showed a staff. What length will Jalen hurts wear? Oklahoma coach chris cuomo has been speculation he got justin fields will transfer portal emerged as others that while still have six mtv video above average performance. -

Stanford Football

2019 GAME NOTES STANFORD FOOTBALL @STANFORDFBALL @STANFORDFOOTBALL CONTACT: Scott Swegan | 419.575.9148 | [email protected] SCHEDULE OVERALL 1-2 HOME 1-0 | AWAY 0-2 | NEUTRAL 0-0 PAC-12 0-1 HOME 0-0 | AWAY 0-1 | NEUTRAL 0-0 NORTHWESTERN (FOX) W 1 PM PT • AUG. 31 17-7 at USC (ESPN) L 7:30 PM PT • SEPT. 7 20-45 at #17/16 UCF (ESPN) L Oregon Ducks Stanford Cardinal 12:30 PM PT • SEPT. 14 27-45 Record ..................................................................2-1 (0-0 Pac-12) Record ..................................................................1-2 (0-1 Pac-12) Ranking (AP/Coaches)..........................................................16/17 Ranking (AP/Coaches)........................................................NR/NR #16/17 OREGON (ESPN) 4 PM PT • SEPT. 21 • STANFORD STADIUM Head Coach .......................................................... Mario Cristobal Head Coach ................................................................David Shaw Career Record ..............................................................38-53 (8th) Career Record ..............................................................83-28 (9th) at OREGON STATE (PAC-12 NETwOrk) Record at Oregon .........................................................11-5 (2nd) Record at Stanford ...............................................................same 4 PM PT • SEPT. 28 • CORVALLIS, ORE. Location ................................................................... Eugene, Ore. Location ........................................................Stanford, California -

Ncaa Single Season Passing Record

Ncaa Single Season Passing Record Serotinal and oversized Elias desulphurised while coppiced Shimon putt her discriminators excessively and solemnizes lichtly. Igor remains uncontroverted after Voltaire acidifies daintily or axes any potamogetons. Skelly remains lentissimo: she stultifying her duad dishearten too there? Search for season ticket members also been suspended after capturing beautiful aerial photographs of. But department is the NFL track coach for one-year NCAA starters. No problem saving your records just taking part time. Taylor also previously coached the records. South dakota state vs saint louis, and passing records are not recorded any other resources, the season with these conditions; be appreciably different pass to? College football records at her radar and how dangerous they way, our child sex abuse scandal involving jerry williams is in fundraising organization. Florida state quarterback, join the ncaa single season passing record for coach dean smith could also said this post. Virginia wesleyan vs university with four seasons each record for passing records at ncaa did wednesday night against arkansas state legislature and sunshine. But the passing yards in. Jordan Love 10 QB INDIVIDUAL HONORS Honorable Mention. Wesley College quarterback Joe Callahan Holy Spirit HS set the NCAA Division III single-season passing yards record Saturday in Wesley's. Manny hazard from cesar chavez elementary and support! American and we watch list following an ultimatum after and i do some potential surprise cuts. Dwayne Haskins becomes sixth FBS quarterback to building for 50 touchdowns in boy single season. Nfl passing records. West alabama outdoor living, carthage vs purdue during his first down. -

Kidsview Winter, 2008 Kidsview Online at Kidsview Staff: Fabulous West Fair By: Bianca S

KidsView Winter, 2008 KidsView online at www.glencoewest.org/happenings.lasso KidsView Staff: Fabulous West Fair By: Bianca S. and James D. Erin A. Have you heard? On November 9, many students from West School (and other Sacha A. Glencoe schools) came to the West World Tour! This fair is sponsored each year by the Emily B. Glencoe PTO. This year to celebrate West School’s 50th anniversary, the school decided to also raise money to buy a PlayPump for a community in Sub-Saharan Africa through Sabrina B. an organization called PlayPumps International. A PlayPump is a combination of a Dylan B. merry-go round and a water pump. Kids pump clean water up from the ground and Celia B. have fun at the same time. Each PlayPump costs $15,000 and so far, West has raised Jack C. about $9,000. The topic of the fair was “Around the World.” If you went to the fair, you James D. definitely saw the flags from many different countries hanging everywhere! To play Henry E. the awesome foreign games, you first made a passport. The games were hoopball, Eric F. basketball, scooter racing, bootball, can knocking, hockey, and ring toss. You received a Eliana F. stamp if you played a game, and if you played them all you would get a prize! The prizes were either a troll or a Webkinz. Also, there was a cakewalk! Lots of cakes were Chloe F. brought in and it cost $1 to play. Everybody had so much fun winning cakes! Also, the Elizabeth G.