Public Right to Access to Remote Hearings During Covid-19 Pandemic1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A&G Goldman P'ship V. Picard (In Re Bernard L. Madoff Inv. Secs. LLC

Neutral As of: July 16, 2018 9:45 PM Z A&G Goldman P’ship v. Picard (In re Bernard L. Madoff Inv. Secs. LLC) United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit June 27, 2018, Decided No. 17-512-bk Reporter 2018 U.S. App. LEXIS 17574 *; 2018 WL 3159228 propping-up, disguised, quotation, collapse IN RE: BERNARD L.MADOFF INVESTMENT SECURITIES LLC, Debtor.A & G GOLDMAN PARTNERSHIP, PAMELA GOLDMAN, Appellants, v. Case Summary IRVING H. PICARD, Trustee for the Liquidation of Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities LLC and Overview Bernard L. Madoff, CAPITAL GROWTH COMPANY, DECISIONS INCORPORATED, FAVORITE FUNDS, JA HOLDINGS: [1]-A suit alleging that an investor in a PRIMARY LIMITED PARTNERSHIP, JA SPECIAL Ponzi scheme and associated entities were liable for LIMITED PARTNERSHIP, JAB PARTNERSHIP, JEMW securities fraud as controlling persons under 15 PARTNERSHIP, JF PARTNERSHIP, JFM U.S.C.S. § 78t(a) was barred by an injunction entered in INVESTMENT COMPANIES, JLN PARTNERSHIP, connection with a Securities Investor Protection Act JMP LIMITED PARTNERSHIP, JEFFRY M. PICOWER trustee's settlement of a fraudulent transfer claim. The SPECIAL CO., JEFFRY M. PICOWER P.C., THE facts alleged did not give rise to a colorable claim that PICOWER FOUNDATION, THE PICOWER INSTITUTE the investor controlled the entity through which the FOR MEDICAL RESEARCH, THE TRUST F/B/O Ponzi scheme was perpetrated, so the substance of the GABRIELLE H. PICOWER, BARBARA PICOWER, allegations amounted to only a derivative fraudulent individually and as Executor of the Estate of Jeffry M. transfer claim. Picower, and as Trustee for the Picower Foundation and for The trust f/b/o Gabrielle H. -

Proposed Amendments to Fed. R. Crim. P. 26: an Exchange: Remote Testimony Richard D

University of Michigan Law School University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository Articles Faculty Scholarship 2002 Proposed Amendments to Fed. R. Crim. P. 26: An Exchange: Remote Testimony Richard D. Friedman University of Michigan Law School, [email protected] Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles/158 Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/articles Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Courts Commons, Criminal Procedure Commons, and the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation Friedman, Richard D. "Remote Testimony." U. Mich. J. L. Reform 35, no. 4 (2002): 695-717. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles by an authorized administrator of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. REMOTE TESTIMONY Richard D. Friedman* Recently, the Supreme Court declined to pass on to Congress a proposed change to FederalRule of Criminal Procedure 26 submitted to it by the Judicial Conference. In this Article, ProfessorFriedman addresses this proposal, which would allow for more extensive use of remote, video-based testimony at criminal trials. He agrees with the majority of the Court that the proposal raised serious problems under the Confrontation Clause. He also argues that a revised proposal, in addition to better protecting the confrontation rights of defendants, should include more definite quality standards,abandon its reliance on the definition of unavailabilityfound in the FederalRules ofEvidence, and allow defendants greaterflexibility in the use of remote testimony. -

Duties and Conduct of Presiding Judge (Feb

Ch. 22: Duties and Conduct of Presiding Judge (Feb. 2018) 22.4 Maintaining Order and Security in the Courtroom A. Controlling Access to/Closure of the Courtroom B. Controlling Access to Other Areas C. Removal of Disruptive Defendant D. Removal of Disruptive Witnesses or Spectators E. Restraint of Defendant and Witnesses During Trial F. Conspicuous Use of Security Personnel G. Contempt Powers and Inherent Authority H. Additional Resources _____________________________________________________________ 22.4 Maintaining Order and Security in the Courtroom A. Controlling Access to/Closure of the Courtroom Generally. Article I, section 18 of the N.C. Constitution requires that “[a]ll courts shall be open,” and section 24 provides that “[n]o person shall be convicted of any crime but by the unanimous verdict of a jury in open court.” Additionally, the Sixth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution mandates that “[i]n all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial.” This right extends to the states through the Fourteenth Amendment. See Presley v. Georgia, 558 U.S. 209 (2010) (defendant’s right to a public trial encompasses the jury selection phase). “The trial and disposition of criminal cases is the public’s business and ought to be conducted in public in open court.” In re Edens, 290 N.C. 299, 306 (1976). In discussing public trials, the U.S. Supreme Court has stated: The requirement of a public trial is for the benefit of the accused; that the public may see he is fairly dealt with and not unjustly condemned, and that the presence of interested spectators may keep his triers keenly alive to a sense of their responsibility and to the importance of their functions. -

Out-Of-Term, Out-Of-Session, Out-Of-County

ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE BULLETIN NUMBER 2008/05 | NOVEMBER 2008 Out-of-Term, Out-of-Session, Out-of-County Michael Crowell For many jurisdictions the concept of a session or term of court is not as important as it is in North Carolina with the state’s legacy of traveling superior court judges. In this state the commonly stated rule, for both criminal and civil cases in both superior and district court, is that a judgment or order affecting substantial rights may not be entered without the consent of the parties (1) after the ses- sion of court has expired, or (2) while the judge is out of the county or district. Actually, there are many instances when orders may be entered out-of-session and out-of-county, especially in civil cases. This bulletin will attempt to describe those situations. Meaning of “Session” and “Term” In common parlance “term of court” and “session” sometimes are used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings. Under the rotation system for superior court judges mandated by article IV, section 11 of the North Carolina Constitution (“The principle of rotating Superior Court Judges among the various districts of a division is a salutary one and shall be observed”), judges are assigned on six-month schedules. Thus in superior court the “use of ‘term’ has come to refer to the typical six-month assignment of superior court judges, and ‘session’ to the typical one-week assignment within the term.” Capital Outdoor Advertising v. City of Raleigh, 337 N.C. 150, 154, 446 S.E.2d 289, 292, n.1, 2 (1994). -

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court

Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court The text of the Rome Statute reproduced herein was originally circulated as document A/CONF.183/9 of 17 July 1998 and corrected by procès-verbaux of 10 November 1998, 12 July 1999, 30 November 1999, 8 May 2000, 17 January 2001 and 16 January 2002. The amendments to article 8 reproduce the text contained in depositary notification C.N.651.2010 Treaties-6, while the amendments regarding articles 8 bis, 15 bis and 15 ter replicate the text contained in depositary notification C.N.651.2010 Treaties-8; both depositary communications are dated 29 November 2010. The table of contents is not part of the text of the Rome Statute adopted by the United Nations Diplomatic Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Establishment of an International Criminal Court on 17 July 1998. It has been included in this publication for ease of reference. Done at Rome on 17 July 1998, in force on 1 July 2002, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 2187, No. 38544, Depositary: Secretary-General of the United Nations, http://treaties.un.org. Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Published by the International Criminal Court ISBN No. 92-9227-232-2 ICC-PIOS-LT-03-002/15_Eng Copyright © International Criminal Court 2011 All rights reserved International Criminal Court | Po Box 19519 | 2500 CM | The Hague | The Netherlands | www.icc-cpi.int Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court Table of Contents PREAMBLE 1 PART 1. ESTABLISHMENT OF THE COURT 2 Article 1 The Court 2 Article 2 Relationship of the Court with the United Nations 2 Article 3 Seat of the Court 2 Article 4 Legal status and powers of the Court 2 PART 2. -

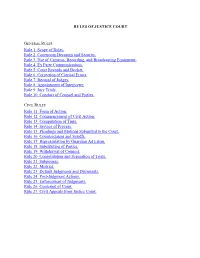

Rule 1 Scope of Rules. Rule 2 Courtroom Decorum and Security

RULES OF JUSTICE COURT GENERAL RULES Rule 1 Scope of Rules. Rule 2 Courtroom Decorum and Security. Rule 3 Use of Cameras, Recording, and Broadcasting Equipment. Rule 4 Ex Parte Communications. Rule 5 Court Records and Docket. Rule 6 Correction of Clerical Errors. Rule 7 Recusal of Judges. Rule 8 Appointment of Interpreter. Rule 9 Jury Trials. Rule 10 Conduct of Counsel and Parties. CIVIL RULES Rule 11 Form of Action. Rule 12 Commencement of Civil Action. Rule 13 Computation of Time. Rule 14 Service of Process. Rule 15 Pleadings and Motions Submitted to the Court. Rule 16 Counterclaims and Setoffs. Rule 17 Representation by Guardian Ad Litem. Rule 18 Substitution of Parties. Rule 19 Withdrawal of Counsel. Rule 20 Consolidation and Separation of Trials. Rule 21 Subpoenas. Rule 22 Mistrial. Rule 23 Default Judgments and Dismissals. Rule 24 Post-Judgment Actions. Rule 25 Enforcement of Judgments. Rule 26 Contempt of Court. Rule 27 Civil Appeals from Justice Court. RULES OF JUSTICE COURT [Adopted effective May 1, 1995; amended effective July 1, 2017; amended effective July 1, 2020] GENERAL RULES RULE 1 SCOPE OF RULES (a) These are the Rules of Justice Court and may be cited as RJC: e.g., RJC 1. They shall govern procedures in justice courts. Rules 1-10 shall be applicable to all cases, whether civil or criminal in nature. Rules 11-27 shall only be applicable to civil cases. The Mississippi Rules of Criminal Procedure shall apply to all criminal cases before the justice courts and shall supersede any conflicting provision of these rules. -

![Article Iii, Sections 1–2]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5614/article-iii-sections-1-2-985614.webp)

Article Iii, Sections 1–2]

CONSTITUTION OF THE UNITED STATES § 177–§ 178 [ARTICLE III, SECTIONS 1–2] In 2009, the House agreed to a resolution reported from the Committee on the Judiciary and called up as a question of the privileges of the House impeaching Federal district judge Samuel B. Kent for high crimes and misdemeanors specified in 4 articles of impeachment, some of them ad- dressing allegations on which the judge had been convicted in a Federal criminal trial (June 19, 2009, p. l). A resolution offered from the floor to permit the Delegate of the District of Columbia to vote on the articles of impeachment was held not to con- stitute a question of the privileges of the House under rule IX (Dec. 18, 1998, p. 27825). To a privileged resolution of impeachment, an amendment proposing instead censure, which is not privileged, was held not germane (Dec. 19, 1998, p. 28100). For further discussion of impeachment proceedings, see §§ 601–620, infra; § 31, supra, and Deschler, ch. 14. ARTICLE III. SECTION 1. The judicial Power of the United § 177. The judges, their States, shall be vested in one su- terms, and compensation. preme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office. SECTION 2. 1 The judicial Power shall extend § 178. Extent of the to all Cases, in Law and Equity, judicial power. -

Josh Hendrickson Name

Circuit Judge's Preference Guide JUDGE CONTACT INFORMATION 1. Please enter your name. Josh Hendrickson Name: ATTORNEY CONTACT 2. Generally, how do you prefer attorney contact? Email 3. How do you prefer to receive briefs? Email 4. Would you like to receive copies of pleadings and Yes, via email with hard copy also sent via U.S. affidavits related to a brief or motion? Mail 5. How do you prefer to receive proposed orders? Email CIVIL SCHEDULING & PRACTICE 6. What is the preferred method for setting a civil Contact Court Administration and attorney may motions hearing, other than in open court? schedule with notice to other attorney 7. Do you want courtesy copies of the main statutes or No cases relied upon in briefs or motions? 8. Who should be contacted to request/schedule a Court Administration telephonic appearance? 9. Do you require a motion or want some form of notice Yes if the parties have stipulated to an extension of a deadline in a scheduling order? 1 / 4 Circuit Judge's Preference Guide 10. Should stipulations between counsel on evidentiary Yes issues and/or legal issues be submitted to you in writing? 11. What is the preferred method for scheduling a civil File a motion for scheduling and set for a motions jury trial? hearing 12. Do your require pretrial conferences and what Yes agenda do you have for pretrial conferences? 13. Do you have a standard pretrial order? No 14. Do you have any requirements for court trials that No are different from your jury trial expectations? 15. -

Rule 43(A): Remote Witness Testimony and a Judiciary Resistant to Change

Fobes_EIC_Proof_Complete (Do Not Delete) 2/23/2020 9:55 AM NOTES & COMMENTS RULE 43(A): REMOTE WITNESS TESTIMONY AND A JUDICIARY RESISTANT TO CHANGE by Christopher Fobes* Technology has improved our lives in countless ways. In 1996, it made its way into our federal courtrooms and the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure when the Congress codified Rule 43(a). Rule 43(a) permits a witness to testify remotely via telephone or video transmission upon a showing of good cause. Despite this large step into the modern era, some courts are pressed to exclude a witness’s remote testimony because of Rule 43(a)’s burdensome good-cause standard and the risks implicated by such testimony. The judiciary has struggled to find co- hesion in determining when remote witness testimony is permissible. This Note critiques some federal courts’ reluctance to allow witnesses to testify remotely and proposes a new rule that would meet the demands of modern society. I. Introduction ......................................................................................... 300 II. The History of Witness Credibility to Fact Finding .............................. 301 A. The History of Open Court Testimony in English Common Law ....... 302 B. The Creation of Rule 43(a) ............................................................. 303 III. Current Rule 43(a) ............................................................................... 305 IV. Courts’ Inconsistent Analysis of Rule 43(a) ........................................... 306 A. Good Cause in Compelling Circumstances ........................................ 307 * Christopher Fobes holds a JD from Lewis & Clark Northwestern School of Law. After high school, he enlisted in the U.S. Marine Corps Infantry and deployed twice to Afghanistan. He wishes to thank Professor Tomás Gómez-Arostegui for his comments and the Honorable Judge Youlee Yim You for her valuable advice. -

Rule 2.1 Adopted Effective January 1, 2007

Title 2. Trial Court Rules Division 1. General Provisions Chapter 1. Title and Application Rule 2.1. Title Rule 2.2. Application Rule 2.1. Title The rules in this title may be referred to as the Trial Court Rules. Rule 2.1 adopted effective January 1, 2007. Rule 2.2. Application The Trial Court Rules apply to all cases in the superior courts unless otherwise specified by a rule or statute. Rule 2.2 amended and renumbered effective January 1, 2007; adopted as rule 200 effective January 1, 2001; previously amended effective January 1, 2002, and January 1, 2003. Chapter 2. Definitions and Scope of Rules Rule 2.3. Definitions Rule 2.10. Scope of rules Rule 2.3. Definitions As used in the Trial Court Rules, unless the context or subject matter otherwise requires: (1) “Court” means the superior court. (2) “Papers” includes all documents, except exhibits and copies of exhibits, that are offered for filing in any case, but does not include Judicial Council and local court forms, records on appeal in limited civil cases, or briefs filed in appellate divisions. Unless the context clearly provides otherwise, “papers” need not be in a tangible or physical form but may be in an electronic form. (3) “Written,” “writing,” “typewritten,” and “typewriting” include other methods of printing letters and words equivalent in legibility to typewriting or printing from a word processor. Rule 2.3 amended effective January 1, 2016; adopted effective January 1, 2007. Rule 2.10. Scope of rules 1 These rules apply to documents filed and served electronically as well as in paper form, unless otherwise provided. -

District of Columbia Courts FY 2022 Budget Justification Table of Contents

FY 2022 Budget Justification District of Columbia Courts Open to All ♦ Trusted by All ♦ Justice for All District of Columbia Courts FY 2022 Budget Justification Table of Contents 1. Summary a. Narrative ....................................................................................................... Summary-1 b. Comparison Table ......................................................................................... Summary-1 c. Priority Table .............................................................................................. Summary-19 d. Organizational Chart ................................................................................... Summary-26 e. Request Summary Table ............................................................................. Summary-27 f. Interagency Agreements Table ................................................................... Summary-30 2. Appropriations Language a. Language ........................................................................... Appropriations Language-31 b. Justification ....................................................................... Appropriations Language-33 3. Initiatives a. Juror Fee Parity .......................................................................................... Initiatives-35 b. Expanding Access to Justice ...................................................................... Initiatives-37 4. Court of Appeals a. Narrative ......................................................................................... Court of Appeals-41 -

Rules for Louisiana District Courts and Juvenile Courts and Louisiana Family Law Proceedings

RULES FOR LOUISIANA DISTRICT COURTS AND JUVENILE COURTS AND LOUISIANA FAMILY LAW PROCEEDINGS (Includes all amendments through May 14, 2020.) RULES FOR LOUISIANA DISTRICT COURTS AND JUVENILE COURTS AND LOUISIANA FAMILY LAW PROCEEDINGS TITLE I RULES FOR PROCEEDINGS IN DISTRICT COURTS, FAMILY COURTS, AND JUVENILE COURTS TITLE II RULES FOR CIVIL PROCEEDINGS IN DISTRICT COURTS TITLE III RULES FOR CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS IN DISTRICT COURTS TITLE IV RULES FOR FAMILY LAW PROCEEDINGS IN DISTRICT COURTS, IN THE FAMILY COURT FOR THE PARISH OF EAST BATON ROUGE, AND PROCEEDINGS IN JUVENILE AND DISTRICT COURTS PURSUANT TO TITLE IV-D OF THE SOCIAL SECURITY ACT TITLE V RULES FOR JUVENILE PROCEEDINGS IN DISTRICT COURTS AND IN JUVENILE COURTS FOR THE PARISHES OF EAST BATON ROUGE, ORLEANS, JEFFERSON, AND CADDO TITLE VI RULES FOR LITIGATION FILED BY INMATES DISTRICT COURT APPENDICES 1 App. Rule Number Appendix Title 1.3 1.3 Amendment Form 2.0 2.0 Local Holidays in Addition to Legal Holidays Listed in La. R.S. 1:55 3.1 3.1 Divisions or Sections of Court 3.2 3.2 Duty Judges 3.4 3.4 Court-Specific Rules Concerning Judges’ Use of Electronic Signatures 3.5 3.5 Court-Specific Rules Concerning Simultaneous Appearance by a Party or Witness by Audio- Visual Transmission 4.1 4.1 Judicial Administrators and Clerks of Court 5.1A 5.1 Americans with Disabilities Form 5.1B 5.1 Request for Interpreter and Order 5.1C 5.1 Interpreter’s Oath 8.0 8.0 In Forma Pauperis Affidavit 9.3 9.3 Allotments; Signing of Pleadings in Allotted and Non-Allotted Cases 9.4 9.4 Presentation of