Home Editorial Authors' Responses Guidelines for Reviewers About Us

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Also by N

THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Also by N. John Hall THE NEW ZEALANDER (editor) SALMAGUNDI: BYRON, ALLEGRA, AND THE TROLLOPE FAMILY TROLLOPE AND HIS ILLUSTRATORS THE TROLLOPE CRITICS Edited by N. John Hall Selection and editorial matter © N. John Hall 1981 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1981 978-0-333-26298-6 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission First published 1981 by THE MACMILLAN PRESS LTD London and Basingstoke Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 978-1-349-04608-9 ISBN 978-1-349-04606-5 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-04606-5 Typeset in 10/12pt Press Roman by STYLESET LIMITED ·Salisbury· Wiltshire Contents Introduction vii HENRY JAMES Anthony Trollope 21 FREDERIC HARRISON Anthony Trollope 21 w. P. KER Anthony Trollope 26 MICHAEL SADLEIR The Books 34 Classification of Trollope's Fiction 42 PAUL ELMER MORE My Debt to Trollope 46 DAVID CECIL Anthony Trollope 58 CHAUNCEY BREWSTER TINKER Trollope 66 A. 0. J. COCKSHUT Human Nature 75 FRANK O'CONNOR Trollope the Realist 83 BRADFORD A. BOOTH The Chaos of Criticism 95 GERALD WARNER BRACE The World of Anthony Trollope 99 GORDON N. RAY Trollope at Full Length 110 J. HILLIS MILLER Self and Community 128 RUTH apROBERTS The Shaping Principle 138 JAMES GINDIN Trollope 152 DAVID SKILTON Trollopian Realism 160 C. P. SNOW Trollope's Art 170 JOHN HALPERIN Fiction that is True: Trollope and Politics 179 JAMES R. KINCAID Trollope's Narrator 196 JULIET McMASTER The Author in his Novel 210 Notes on the Authors 223 Selected Bibliography 226 Index 243 Introduction The criticism of Trollope's works brought together in this collection has been drawn from books and articles published since his death. -

Trollopiana 100 Free Sample

THE JOURNAL OF THE Number 100 ~ Winter 2014/15 Bicentenary Edition EDITORIAL ~ 1 Contents Editorial Number 100 ~ Winter 2014-5 his 100th issue of Trollopiana marks the beginning of our FEATURES celebrations of Trollope’s birth 200 years ago on 24th April 1815 2 A History of the Trollope Society Tat 16 Keppel Street, London, the fourth surviving child of Thomas Michael Helm, Treasurer of the Trollope Society, gives an account of the Anthony Trollope and Frances Milton Trollope. history of the Society from its foundation by John Letts in 1988 to the As Trollope’s life has unfolded in these pages over the years present day. through members’ and scholars’ researches, it seems appropriate to begin with the first of a three-part series on the contemporary criticism 6 Not Only Ayala Dreams of an Angel of Light! If you have ever thought of becoming a theatre angel, now is your his novels created, together with a short history of the formation of our opportunity to support a production of Craig Baxter’s play Lady Anna at Society. Sea. During this year we hope to reach a much wider audience through the media and publications. Two new books will be published 7 What They Said About Trollope At The Time Dr Nigel Starck presents the first in a three-part review of contemporary by members: Dispossessed, the graphic novel based on John Caldigate by critical response to Trollope’s novels. He begins with Part One, the early Dr Simon Grennan and Professor David Skilton, and a new full version years of 1847-1858. -

A CHRONOLOGY of Trollope's Life and Times Adapted from A

A CHRONOLOGY of Trollope’s life and times Adapted from a chronology in the Penguin editions of Trollope’s Barchester and Palliser novels KEY Events in Trollope’s life Trollope’s writing1 Events in the wider world Works of other writers ____________________________________________________________________________ 1815 Battle of Waterloo Lord George Gordon Byron, Hebrew Melodies ANTHONY TROLLOPE BORN 24 APRIL AT 16 KEPPEL STREET, BLOOMSBURY, THE FOURTH SON OF THOMAS AND FRANCES TROLLOPE. Family moves shortly after to Harrow-on-the-Hill 1823 Trollope attends Harrow as a day-boy (1825) 1825 First public steam railway opened Sir Walter Scott, The Betrothed and The Talisman Sent as a boarder to a private school in Sunbury, Middlesex 1827 Greek War of Independence won in the battle of Navarino Sent to school at Winchester College. His mother sets sail for the USA on 4 November with three of her children 1830 George IV dies; his brother ascends the throne as William IV William Cobbett, Rural Rides Removed from Winchester. Sent again to Harrow until 1834. 1832 Controversial First Reform Act extends the right to vote to approximately one man in five Frances Trollope, Domestic Manners of the Americans 1834 Slavery abolished in the British Empire. Poor Law Act introduces workhouses to England. Edward Bulwer-Lytton, The Last Days of Pompeii Trollope family migrates to Bruges to escape creditors. Anthony returns to London to take up a junior clerkship in the General Post Office. 1835 Halley’s Comet appears ‘Railway mania’ in Britain Robert Browning, Paracelsus Trollope’s father dies in Bruges 1840 Queen Victoria marries Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha. -

Dissent Women in Anthony Trollope's Fiction: a Sympathetic Portrayal

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1993 Dissent women in Anthony Trollope's fiction: A sympathetic portrayal Elisabeth Morton McLaren University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation McLaren, Elisabeth Morton, "Dissent women in Anthony Trollope's fiction: A sympathetic portrayal" (1993). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 2982. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/uqts-wcbg This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced frommicrofilm the master, UMI film s the text directly from theoriginal or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent uponq u a lity theof the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandardmargins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Forced Execution of the Elderly: Old Law, Dystopia, and the Utilitarian Argument

Humanities 2013, 2, 160–175; doi:10.3390/h2020160 OPEN ACCESS humanities ISSN 2076-0787 www.mdpi.com/journal/humanities Article Forced Execution of the Elderly: Old Law, Dystopia, and the Utilitarian Argument Sara D. Schotland Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton LLP, 2000 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20006, USA; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-202-974-1550 Received: 27 March 2013; in revised form: 20 April 2013 / Accepted: 23 April 2013 / Published: 29 April 2013 Abstract: This essay focuses on a play that Thomas Middleton co-authored on the topic of forced execution of the elderly, The Old Law (1618–1619). Here, the Duke of Epire has issued an edict requiring the execution of men when they reach age eighty and women when they reach age sixty—a decree that is justified on the basis that at these ages, they are a burden to themselves and their heirs, as well as useless to society. I argue that Old Law responds to an issue as old as Plato and as recent as twenty-first century dystopic fiction: should a society devote substantial resources to caring for the unproductive elderly? The conflict between Cleanthes and Simonides about the merits of the decree anticipates the debate between proponents of utilitarian economics and advocates of the bioethical philosophy that we today describe as the Ethics of Care. Keywords: Geronticide; utopia; dystopia; allocation of health care resources; aging 1. Introduction Following the publication of the new Oxford edition of Thomas Middleton’s collected works [1], Middleton, who lived from 1580–1627, has emerged as one of Shakespeare’s most distinguished contemporaries [2]. -

GR68 Getting-On.FINAL2 .Pdf

•GriffithREVIEW68.indb 1 5/3/20 1:49 pm Praise for Griffith Review ‘A literary degustation... The richness of these stories is amplified by the resonance between them. It’s hard to think of so much fascinating story being contained within 270-odd pages.’ Ed Wright, The Saturday Australian ‘…informative, thought-provoking and well-crafted.’ The Saturday Paper ‘[An] outstanding collection of essays, reportage, memoir, poetry and fiction.’ Mark McKenna, Honest History ‘The Review doesn’t shirk from the nuanced and doesn’t seek refuge in simplistic notions or slogans. It remains Australia’s primary literary review.’ Professor Ken Smith, Dean and CEO ANZSOG ‘Griffith Review continues to provide a timely focus on contemporary topics through its high-calibre collection of literary works.’ Graham Quirk, former Lord Mayor, Brisbane ‘…an eclectic, thought-provoking and uniformly well-written collection.’ Justin Burke, The Australian ‘This is commentary of a high order. The prose is unfailingly polished; the knowledge and expertise of the writers impressive.’ Roy Williams, Sydney Morning Herald ‘For intelligent, well-written quarterly commentary…Griffith Review remains the gold standard.’ Honest History ‘Griffith Review is Australia’s most prestigious literary journal.’ stuff.co.nz ‘Griffith Review is a must-read for anyone with even a passing interest in current affairs, politics, literature and journalism. The timely, engaging writing lavishly justifies the Brisbane-based publication’s reputation as Australia’s best example of its genre.’ The West Australian ‘Griffith Review enjoys a much-deserved reputation as one of the best literary journals in Australia. Its contribution to conversations and informed debate on a wide range of topical issues has been outstanding.’ Hon. -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88636-9 - The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope Edited by Carolyn Dever and Lisa Niles Frontmatter More information the cambridge companion to anthony trollope Anthony Trollope was among the most prolific, popular, and richly diverse writers of the mid-Victorian period, with forty-seven novels and a variety of other writings to his name. Both a serial and a series writer whose novels traversed Ireland, England, Australia, and New Zealand, and genres from realism to science fiction, Trollope also published criticism, short fiction, travel writing, and biography. The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope provides a state-of-the-field review of critical perspectives on his work, with the volume’s essays addressing Trollope’s biography, autobiography, canonical fiction, short stories, and travel writing, as well as surveying diverse topics including gender, sexuality, vulgarity, and the law. A complete list of the books in the series is at the back of this book. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88636-9 - The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope Edited by Carolyn Dever and Lisa Niles Frontmatter More information Frontispiece. Anthony Trollope, after Sir Leslie Ward. Chromolithograph, published 1873. Reprinted with the permission of the National Portrait Gallery. NPG d32583. © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-88636-9 - The Cambridge Companion to Anthony Trollope -

Anthony Trollope*S Literary Reputation;

ANTHONY TROLLOPE*S LITERARY REPUTATION; ITS DEVELOPMENT AND VALIDITY by ELLA KATHLEEN GRANT A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for. the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of English The University of British Columbia, October, 1950. This essay attempts to trace the course of Anthony Trollope's literary reputation; to suggest some explan• ations for the various spurts and sudden declines of his popularity among readers and esteem among critics; and to prove that his mid-twentieth century position is not a just one. Drawing largely on Trollope's Autobiography, contemp• orary reviews and essays on his work, and references to it in letters and memoirs, the first chapter describes Trollope's writing career, showing him rising to popu• larity in the late fifties and early sixties as a favour• ite among readers tired of sensational fiction, becoming a byword for commonplace mediocrity in the seventies, and finally, two years before his death, regaining much of his former eminence among older readers and conservative critics. Throughout the chapter a distinction is drawn between the two worlds with which Trollope deals, Barset- shire and materialist society, and the peculiarly dual nature of his work is emphasized. Chapter II is largely concerned with the vicissitudes that Trollope's reputation has encountered since the post• humous publication of his autobiography. During the de• cade following his death he is shown as an object of comp• lete contempt to the Art for Art's Sake school, finally rescued around the turn of the century by critics reacting against the ideals of his detractors. -

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope

Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Anthony Trollope Autobiography of Anthony Trollope Table of Contents Autobiography of Anthony Trollope.......................................................................................................................1 Anthony Trollope...........................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. MY EDUCATION 1815−1834...............................................................................................3 CHAPTER II. MY MOTHER.......................................................................................................................8 CHAPTER III. THE GENERAL POST OFFICE 1834−1841....................................................................12 CHAPTER IV. IRELANDMY FIRST TWO NOVELS 1841−1848........................................................20 CHAPTER V. MY FIRST SUCCESS 1849−1855......................................................................................26 CHAPTER VI. "BARCHESTER TOWERS" AND THE "THREE CLERKS" 1855−1858......................32 CHAPTER VII. "DOCTOR THORNE""THE BERTRAMS""THE WEST INDIES" AND "THE SPANISH MAIN".......................................................................................................................................37 CHAPTER VIII. THE "CORNHILL MAGAZINE" AND "FRAMLEY PARSONAGE".........................41 -

Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope

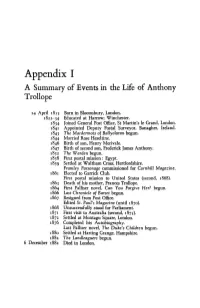

Appendix I A Summary of Events in the Life of Anthony Trollope 24 April 1815 Born in Bloomsbury, London. 1822-34 Educated at Harrow; Winchester. 1834 Joined General Post Office, StMartin's le Grand, London. 1841 Appointed Deputy Postal Surveyor, Banagher, Ireland. 1843 The Macdermots of Ballycloran begun. 1844 Married Rose Heseltine. 1846 Birth of son, Henry Merivale. 1847 Birth of second son, Frederick James Anthony. 1852 The Warden begun. 1858 First postal mission: Egypt. 1859 Settled at Waltham Cross, Hertfordshire. Framley Parsonage commissioned for Cornhill Magazine. 1861 Elected to Garrick Club. First postal mission to United States (second, 1868). 1863 Death of his mother, Frances Trollope. 1864 First Palliser novel, Can You Forgive Her? begun. 1866 Last Chronicle of Barset begun. 1867 Resigned from Post Office. Edited St. Paul's Magazine (until187o). 1868 Unsuccessfully stood for Parliament. 1871 First visit to Australia (second, 1875). 1872 Settled at Montagu Square, London. 1876 Completed his Autobiography. Last Palliser novel, The Duke's Children begun. 188o Settled at Harting Grange, Hampshire. 1882 The Landleagu.ers begun. 6 December 1882 Died in London. Appendix II Bibliography of Anthony Trollope (i) MAJOR WORKS The Macdermots of Ballydoran, 3 vols, London: T. C. Newby, 1847 [abridged in one volume, Chapman & Hall's 'New Edition', 1861]. The Kellys and the O'Kellys: or Landlords and Tenants, 3 vols, London: Henry Colburn, 1848. La Vendee: An Historical Romance, 3 vols, London: Colburn, 185o. The Warden, 1 vol, London: Longman, 1855. Barchester Towers, 3 vols, London: Longman, 1857. The Three Clerks: A Novel, 3 vols, London: Bentley, 1858. -

The Novel-Machine Kendrick, Walter

The Novel-Machine Kendrick, Walter Published by Johns Hopkins University Press Kendrick, Walter. The Novel-Machine: The Theory and Fiction of Anthony Trollope. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980. Project MUSE. doi:10.1353/book.68476. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/68476 [ Access provided at 29 Sep 2021 12:38 GMT with no institutional affiliation ] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. HOPKINS OPEN PUBLISHING ENCORE EDITIONS Walter M. Kendrick The Novel-Machine The Theory and Fiction of Anthony Trollope Open access edition supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities / Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Humanities Open Book Program. © 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press Published 2019 Johns Hopkins University Press 2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363 www.press.jhu.edu The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. CC BY-NC-ND ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3402-5 (open access) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3402-4 (open access) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3400-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3400-8 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-13: 978-1-4214-3401-8 (electronic) ISBN-10: 1-4214-3401-6 (electronic) This page supersedes the copyright page included in the original publication of this work. THE NOVEL-MACHINE ��� The Novel-Machine The Theory and Fiction of Anthony Trollope Walter M. Kendrick The Johns Hopkins University Press Baltimore and London This book was brought to publication with the generous assistance of the Andrew W. -

The Pennsylvania State University the Graduate School College of The

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts THE RHETORIC OF EMPIRE AND THE FICTION OF ANTHONY TROLLOPE A Dissertation in English by Lisa Eutsey © 2009 Lisa Eutsey Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2009 The dissertation of Lisa Eutsey was reviewed and approved* by the following: Robert Lougy Professor of English Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee Christopher Clausen Professor of English, Emeritus Lisa Sternlieb Associate Professor of English Mrinalini Sinha Professor of History Robert R. Edwards Graduate Director *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School ii Abstract This dissertation addresses the lack of postcolonial criticism concerning the fiction of Anthony Trollope, himself an avid traveler in and writer about the British Empire. Chapter One provides background about the critical reception of Trollope’s writings about the Empire and traces his attitudes about foreign cultures and the superiority of English culture. I offer a textual reading of Trollope’s short story “A Ride across Palestine” to demonstrate how anxiety about the empire surfaces when Trollope relinquishes his usual narrative voice and uses a more risky first person narrator. Chapter Two compares and contrasts what were in Trollope’s opinion his best and worst writings. Through an analysis of his travel narrative The West Indies and the Spanish Main and his novel He Knew He Was Right I make an argument that He Knew He Was Right was written as a response to the Governor Eyre controversy as it contrasts marital relationships with colonial ones. Chapter Three contextualizes the Cain/Hopkins paradigm of gentlemanly capitalism and argues that Trollope’s The Way We Live Now and The Prime Minister, using the figure of Trollope’s bête noir Disraeli, both warn of the dangers of speculation and imperial expansion into foreign markets.