Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Metro Briefssouth BAY Ably Missing the Fantastic Local Fireworks Anything Wrong with That, by the Way

Page 8 July 16, 2009 EL SEGUNDO HERALD Baseball Season Gearing up Frankly Plank By Duane Plank for Second Half Catching up on a few of the tidbits that to TMZ, and the reporting on the nocturnal By Duane Plank have surfaced in the past week or so while adventures of the locals to...hopefully nobody. Did you get a chance to watch MLB drop-dead change-up? Must be his mechanics, I have been helping coach the Gundo Little Wouldn’t want to alienate my sources, or All-Star festivities earlier this week from but if that is true, wouldn’t dozens of other League All-Star team. We took the first step burn any bridges, would I? the City of Budweiser, St. Louis, Mo.? The young pitchers have copied the seemingly on the road to Williamsport by capturing the Gotta pass on this one Jackson joke, though. midway point in the marathon season is a offbeat wind-up and had similar success? District 36 championship last weekend. The Which isn’t mean at all to the K.O.P., who good time to take a look at some of the hits Suffice to say that the Lincecum legend kids trounced the boys from Palos Verdes 14-3 for some reason, began wearing a single and misses thus far, and look towards the should continue to grow in the second half in the finale to cruise through the tourney white glove during his appearances many playoffs in October. of the season. And when you add fellow 4-0. Next stop is the Sectionals, starting this full moons ago. -

TIM RAINES' HALL of FAME CASE (Pdf)

UP, UP, & AWAY brighter by the constant presence of Expos players. A few of them would show up to teach baseball skills and talk to campers for $100, maybe $200 for a couple hours; most of them did it for free. Raines was one of them. The campers sure as hell remember. “I was six, maybe seven years old, and I remember Raines being there,” said Brian Benjamin, who along with Elan Satov, Eric Kligman, and Andrew “Bean” Kensley formed the core of the Maple Ridge Boys, the group of classmates who accompanied me to hundreds of games at the Big O growing up. “He was hitting balls out of the park, onto the street, and I just stood there in awe watching. Then he came over and talked to us for a long time. I mean, I loved Tim Raines.” Unfortunately, and unfairly, the voting members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America haven’t loved Raines as much. aTIM RAINES’ HALL OF FAME CASEb At this writing, Raines has come up for Hall of Fame induction seven times, and been rejected seven times. This is ridiculous. From 1981 through 1990 with the Expos, Raines hit .302 and posted a .391 on-base percentage (second-best in the NL). During that time he drew 769 walks, just 17 behind the first- place Dale Murphy among National League players in those 10 seasons. Raines stole a league-leading 626 bases, more than Cardinals speedster Vince Coleman, and nearly twice as many as the number-three player on the list, Coleman’s teammate Ozzie Smith. -

Weekly Notes 072817

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES FRIDAY, JULY 28, 2017 BLACKMON WORKING TOWARD HISTORIC SEASON On Sunday afternoon against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Coors Field, Colorado Rockies All-Star outfi elder Charlie Blackmon went 3-for-5 with a pair of runs scored and his 24th home run of the season. With the round-tripper, Blackmon recorded his 57th extra-base hit on the season, which include 20 doubles, 13 triples and his aforementioned 24 home runs. Pacing the Majors in triples, Blackmon trails only his teammate, All-Star Nolan Arenado for the most extra-base hits (60) in the Majors. Blackmon is looking to become the fi rst Major League player to log at least 20 doubles, 20 triples and 20 home runs in a single season since Curtis Granderson (38-23-23) and Jimmy Rollins (38-20-30) both accomplished the feat during the 2007 season. Since 1901, there have only been seven 20-20-20 players, including Granderson, Rollins, Hall of Famers George Brett (1979) and Willie Mays (1957), Jeff Heath (1941), Hall of Famer Jim Bottomley (1928) and Frank Schulte, who did so during his MVP-winning 1911 season. Charlie would become the fi rst Rockies player in franchise history to post such a season. If the season were to end today, Blackmon’s extra-base hit line (20-13-24) has only been replicated by 34 diff erent players in MLB history with Rollins’ 2007 season being the most recent. It is the fi rst stat line of its kind in Rockies franchise history. Hall of Famer Lou Gehrig is the only player in history to post such a line in four seasons (1927-28, 30-31). -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

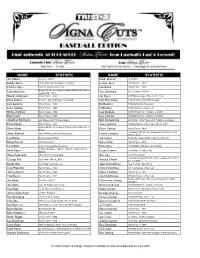

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

College Baseball Foundation January 30, 2008 Boyd, Thank You For

College Baseball Foundation P.O. Box 6507 Phone: 806-742-0301 x249 Lubbock TX 79493-6507 E-mail: [email protected] January 30, 2008 Boyd, Thank you for participating in the balloting for the College Baseball Hall of Fame’s 2008 Induction Class. We appreciate your willingness to help. In the voters packet you will find the official ballot, an example ballot, and the nominee biographies: 1. The official ballot is what you return to us. Please return to us no later than Mon- day, February 11. 2. The example ballot’s purpose is to demonstrate the balloting rules. Obviously the names on the example ballot are not the nominee names. That was done to prevent you from being biased by the rankings you see there. 3. Each nominee has a profile in the biography packet. Some are more detailed than others and reflect what we received from the institutions and/or obtained in our own research. The ballot instructions are somewhat detailed, so be sure to read the directions at the top of the official ballot. Use the example ballot as a reference. Please try to consider the nominees based on their collegiate careers. In many cases nominees have gone on to professional careers but keep the focus on his college career as a player and/or coach. The Veterans (pre-1947) nominees often lack biographical details relative to those in the post-1947 categories. In those cases, the criteria may take on a broader spectrum to include the impact they had on the game/history of college baseball, etc. -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

2011-Mlb-Team-Labels

2011 Baltimore Orioles Record: 69 - 93 5th Place American League East Manager: Buck Showalter Oriole Park at Camden Yards - 45,971 April/May/September/October Day: 1-8 Good, 9-15 Average, 16-20 Bad Night: 1-4 Good, 5-15 Average, 16-20 Bad June/July/August Day: 1-10 Good, 11-17 Average, 18-20 Bad Night: 1-7 Good, 8-17 Average, 18-20 Bad Fence Height: L: 7', LC: 7', C: 7', RC: 7', R: 25' 2011 Boston Red Sox Record: 90 - 72 3rd Place American League East Manager: Terry Francona Fenway Park - 37,065 (day), 37,493 (night) April/May/September/October Day: 1-7 Good, 8-14 Average, 15-20 Bad Night: 1-3 Good, 4-13 Average, 14-20 Bad June/July/August Day: 1-11 Good, 12-17 Average, 18-20 Bad Night: 1-7 Good, 8-17 Average, 18-20 Bad Fence Height: L: 37', LC: 18', C: 9', RC: 5', R: 3' 2011 Chicago White Sox Record: 79 - 83 3rd Place American League Central Manager: Ozzie Guillen, Don Cooper (9/26/11) U.S. Cellular Field - 40,615 April/May/September/October Day: 1-7 Good, 8-14 Average, 15-20 Bad Night: 1-4 Good, 5-13 Average, 14-20 Bad June/July/August Day: 1-11 Good, 12-17 Average, 18-20 Bad Night: 1-7 Good, 8-17 Average, 18-20 Bad Fence Height: L: 8', LC: 8', C: 8', RC 8', R: 8' 2011 Cleveland Indians Record: 80 - 82 2nd Place American League Central Manager: Manny Acta Progressive Field - 43,441 April/May/September/October Day: 1-6 Good, 7-13 Average, 14-20 Bad Night: 1-3 Good, 4-11 Average, 12-20 Bad June/July/August Day: 1-11 Good, 12-17 Average, 18-20 Bad Night: 1-7 Good, 8-17 Average, 18-20 Bad Fence Height: L: 19', LC: 19', C: 9', RC, R: 9' -

SOMERSET PATRIOTS SIX-TIME ATLANTIC LEAGUE CHAMPIONS New Jersey Blasters (0-0) @ Somerset Patriots (0-0) Somerset Patriots

SOMERSET PATRIOTS SIX-TIME ATLANTIC LEAGUE CHAMPIONS 1 Patriots Park * Bridgewater, NJ 08807 * 908.252.0700 www.somersetpatriots.com New Jersey Blasters (0-0) @ Somerset Patriots (0-0) Game #1 * Friday, July 17th * 7:05 p.m. * TD Bank Ballpark * Bridgewater, New Jersey LISTEN: 1450 WCTC; WCTCam.com WATCH: YouTube.com/somersetpatriots UPDATES: @SOMPatriots @NJBlasters Weekend at a glance Friday (7:05) NJB [RHP] Vin Mazzaro (0-0, 0.00 ERA) @ SOM [RHP] David Kubiak (0-0, 0.00 ERA) Saturday (7:05) NJB [LHP] Brandon Liebrandt (0-0, 0.00 ERA) @ SOM [RHP] Mark Leiter Jr. (0-0, 0.00 ERA) PATRIOTS VS. New Jersey Blasters BLASTERS Somerset Patriots Date SITE RESULT BLASTING ON TO THE SCENE: The New Jersey Blasters were 07/17 vs NJB FIRST IN STATE: When the first pitch is thrown on Friday officially announced as the SOMSERSET Professional Baseball 07/18 vs NJB night in the SOMERSET Professional Baseball Series, it will mark Series opponent of the Patriots at a press conference on July 7th 07/24 vs NJB the first professional baseball game in the state of New Jersey in 07/25 vs NJB 2020. The Washington Wild Things (Washington, Penn.) are the ORIGIN OF THE TEAM: The Bridgewater Blasters were 07/31 vs NJB closest organization to Somerset to play professional baseball included amongst the original Somerset Ballpark plans in the 08/01 vs NJB late 90s as a co-inhabitant professional baseball club with the 08/07 vs NJB THE JODIE FILE: The Patriots will be managed by returning Somerset Patriots. -

Changing a Team's Wrc+ Statistic

Changing a Team's wRC+ Statistic This is the seventh of a series of preseason articles about the impact of air density on baseball performance, written for DailyBaseballData.com by Clifton Neeley of www.baseballVMI.com . Even casual observers understand that the Colorado Rockies are the single most unique team ever to compete in Major League Baseball. They have the highest home batting average of any team ever over the course of their history and maintain the highest home winning percent over their history. But, coupling those gaudy home numbers with the lowest road batting averages and win percent, as well as recent revelations of their Weighted Runs Created, Plus (wRC+) statistic, the Rockies remain an anomaly, almost indescribable. A recent article in the Denver Post by writer Patrick Saunders pointed out the wRC+ road statistic as being the worst in the league in spite of the overall high scoring production. Mr. Saunders also outlined the management's planned attempt to bring the road stat into more normal ranges. To be fair, the management has their hands tied. Each year the Rockies add another statistical anomaly without being able to fix any, and the team has done nothing in terms of facilities to prepare for the future, so a new idea must be born every year in order to promise the fans a reason to buy tickets. Just as all the other teams in the league have done for years, they promise a new player, a new coach or manager, and/or a new focus on bringing the most recently exposed anomaly into conformity with the balance of the league. -

Analyzing the Parallelism Between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S. Greene Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Canadian History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Greene, Daniel S., "Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement" (2011). Honors Theses. 988. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/988 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement By Daniel Greene Senior Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Department of History Union College June, 2011 i Greene, Daniel Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement My Senior Project examines the parallelism between the movement to bring baseball to Quebec and the Quebec secession movement in Canada. Through my research I have found that both entities follow a very similar timeline with highs and lows coming around the same time in the same province; although, I have not found any direct linkage between the two. My analysis begins around 1837 and continues through present day, and by analyzing the histories of each movement demonstrates clearly that both movements followed a unique and similar timeline. -

They Played for the Love of the Game Adding to the Legacy of Minnesota Black Baseball Frank M

“Good Grief!” RAMSEY COUNTY Said Charlie Brown: The Business of Death in Bygone St. Paul Moira F. Harris and Leo J. Harris A Publication of the Ramsey County Historical Society —Page 14 Spring 2010 Volume 44, Number 4 They Played for the Love of the Game Adding to the Legacy of Minnesota Black Baseball Frank M. White Page 3 John Cotton, left, was an outstanding athlete and second baseman for the Twin City Gophers, his Marshall Senior High School team, and other professional teams in the 1940s and ’50s. He and Lloyd “Dulov” Hogan, right, and the other unidentified player in this photo were part of the thriving black baseball scene in Minnesota in the middle of the twentieth century. Photo courtesy of the Cotton family. Photo restoration by Lori Gleason. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY RAMSEY COUNTY Executive Director Priscilla Farnham Founding Editor (1964–2006) Virginia Brainard Kunz Editor Hıstory John M. Lindley Volume 45, Number 1 Spring 2010 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE MISSION STATEMENT OF THE RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ON DECEMBER 20, 2007: Thomas H. Boyd The Ramsey County Historical Society inspires current and future generations President Paul A. Verret to learn from and value their history by engaging in a diverse program First Vice President of presenting, publishing and preserving. Joan Higinbotham Second Vice President Julie Brady Secretary C O N T E N T S Carolyn J. Brusseau Treasurer 3 They Played for the Love of the Game Norlin Boyum, Anne Cowie, Nancy Randall Dana, Cheryl Dickson, Charlton Adding to the Legacy of Minnesota Black Baseball Dietz, Joanne A. -

Official 2003 NCAA Baseball & Softball Records Book

Baseball Award Winners American Baseball Coaches Association— Division I All-Americans By College.................. 160 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division I All-America Teams (1947-2002) ............. 162 Baseball America— Division I All-America Teams (1981-2002) ............. 165 Collegiate Baseball— Division I All-America Teams (1991-2002) ............. 166 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division II All-Americans By College................. 166 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division II All-America Teams (1969-2002) ............ 168 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division III All-Americans By College................ 170 American Baseball Coaches Association— Division III All-America Teams (1976-2002) ........... 171 Individual Awards .............................................. 173 160 AMERICAN BASEBALL COACHES ASSOCIATION—DIVISION I ALL-AMERICANS BY COLLEGE 97—Tim Hudson 88—Bert Heffernan 58—Dick Howser All-America 95—Ryan Halla 80—Tim Teufel 57—Dick Howser 89—Frank Thomas 75—Denny Walling FORDHAM (1) Teams 88—Gregg Olson 67—Rusty Adkins 97—Mike Marchiano 67—Q. V. Lowe 60—Tyrone Cline 62—Larry Nichols 59—Doug Hoffman FRESNO ST. (12) 47—Joe Landrum 97—Giuseppe Chiaramonte American Baseball BALL ST. (2) 91—Bobby Jones Coaches 02—Bryan Bullington COLGATE (1) 89—Eddie Zosky 86—Thomas Howard 55—Ted Carrangele Tom Goodwin Association BAYLOR (6) COLORADO (2) 88—Tom Goodwin 01—Kelly Shoppach 77—Dennis Cirbo Lance Shebelut 99—Jason Jennings 73—John Stearns John Salles DIVISION I ALL- 77—Steve Macko COLORADO ST. (1) 84—John Hoover AMERICANS BY COLLEGE 54—Mickey Sullivan 77—Glen Goya 82—Randy Graham (First-Team Selections) 53—Mickey Sullivan 78—Ron Johnson 52—Larry Isbell COLUMBIA (2) 72—Dick Ruthven 84—Gene Larkin ALABAMA (4) 51—Don Barnett BOWDOIN (1) 65—Archie Roberts 97—Roberto Vaz 53—Fred Fleming GEORGIA (1) CONNECTICUT (3) 86—Doug Duke BRIGHAM YOUNG (10) 87—Derek Lilliquist 83—Dave Magadan 63—Eddie Jones 94—Ryan Hall GA.