TIM RAINES' HALL of FAME CASE (Pdf)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gether, Regardless Also Note That Rule Changes and Equipment Improve- of Type, Rather Than Having Three Or Four Separate AHP Ments Can Impact Records

Journal of Sports Analytics 2 (2016) 1–18 1 DOI 10.3233/JSA-150007 IOS Press Revisiting the ranking of outstanding professional sports records Matthew J. Liberatorea, Bret R. Myersa,∗, Robert L. Nydicka and Howard J. Weissb aVillanova University, Villanova, PA, USA bTemple University Abstract. Twenty-eight years ago Golden and Wasil (1987) presented the use of the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for ranking outstanding sports records. Since then much has changed with respect to sports and sports records, the application and theory of the AHP, and the availability of the internet for accessing data. In this paper we revisit the ranking of outstanding sports records and build on past work, focusing on a comprehensive set of records from the four major American professional sports. We interviewed and corresponded with two sports experts and applied an AHP-based approach that features both the traditional pairwise comparison and the AHP rating method to elicit the necessary judgments from these experts. The most outstanding sports records are presented, discussed and compared to Golden and Wasil’s results from a quarter century earlier. Keywords: Sports, analytics, Analytic Hierarchy Process, evaluation and ranking, expert opinion 1. Introduction considered, create a single AHP analysis for differ- ent types of records (career, season, consecutive and In 1987, Golden and Wasil (GW) applied the Ana- game), and harness the opinions of sports experts to lytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) to rank what they adjust the set of criteria and their weights and to drive considered to be “some of the greatest active sports the evaluation process. records” (Golden and Wasil, 1987). -

Introduction

11 INTRODUCTION As the 20th century melted into the 21st, the well-meaning folks at Minor League Baseball made plans to celebrate the 100 greatest teams in the history of the minors since 1901. A hundred teams for 100 years. Assigned to rank the teams were highly respected baseball historians Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright. The job — as with all efforts like this — was a thankless one for Weiss and Wright. Really now, who could say for sure if the 1920 St. Paul Saints, who were No. 6 on their list, were that much better than, say, the 1990 West Palm Beach Expos, who checked in at No. 89? C’mon, were the 1903 Jersey City Skeeters appreciably better at No. 7 than the 1983 Reading Phillies were at 62? How does one differentiate between teams? The teams ranked in the Top 100 played in different classifications in dramatically different eras with demographics that kept teams in the minors from being nothing more than a whites-only club until 1946, when Jackie Robinson made his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers’ top farm team in Montreal. These variables made the rankings flawed from the outset, when the 1944 Milwaukee Brewers were the first team announced at No. 100. Eventually, the countdown reached 73, and that was where Minor League Baseball placed the 1993 Harrisburg Senators. Seventy-freaking-third. Anybody who saw that team knew better. More than 15 years after its release at the turn of the new millennium, the MiLB Top 100 list — specifically, Harrisburg’s ranking — still irked Jim Tracy, the Senators’ manager in 1993. -

Tml American - Single Season Leaders 1954-2016

TML AMERICAN - SINGLE SEASON LEADERS 1954-2016 AVERAGE (496 PA MINIMUM) RUNS CREATED HOMERUNS RUNS BATTED IN 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE .422 57 ♦MICKEY MANTLE 256 98 ♦MARK McGWIRE 75 61 ♦HARMON KILLEBREW 221 57 TED WILLIAMS .411 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 235 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 73 16 DUKE SNIDER 201 86 WADE BOGGS .406 61 MICKEY MANTLE 233 99 MARK McGWIRE 72 54 DUKE SNIDER 189 80 GEORGE BRETT .401 98 MARK McGWIRE 225 01 BARRY BONDS 72 56 MICKEY MANTLE 188 58 TED WILLIAMS .392 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 220 61 HARMON KILLEBREW 70 57 TED WILLIAMS 187 61 NORM CASH .391 01 JASON GIAMBI 215 61 MICKEY MANTLE 69 98 MARK McGWIRE 185 04 ICHIRO SUZUKI .390 09 ALBERT PUJOLS 214 99 SAMMY SOSA 67 07 ALEX RODRIGUEZ 183 85 WADE BOGGS .389 61 NORM CASH 207 98 KEN GRIFFEY Jr. 67 93 ALBERT BELLE 183 55 RICHIE ASHBURN .388 97 LARRY WALKER 203 3 tied with 66 97 LARRY WALKER 182 85 RICKEY HENDERSON .387 00 JIM EDMONDS 203 94 ALBERT BELLE 182 87 PEDRO GUERRERO .385 71 MERV RETTENMUND .384 SINGLES DOUBLES TRIPLES 10 JOSH HAMILTON .383 04 ♦ICHIRO SUZUKI 230 14♦JONATHAN LUCROY 71 97 ♦DESI RELAFORD 30 94 TONY GWYNN .383 69 MATTY ALOU 206 94 CHUCK KNOBLAUCH 69 94 LANCE JOHNSON 29 64 RICO CARTY .379 07 ICHIRO SUZUKI 205 02 NOMAR GARCIAPARRA 69 56 CHARLIE PEETE 27 07 PLACIDO POLANCO .377 65 MAURY WILLS 200 96 MANNY RAMIREZ 66 79 GEORGE BRETT 26 01 JASON GIAMBI .377 96 LANCE JOHNSON 198 94 JEFF BAGWELL 66 04 CARL CRAWFORD 23 00 DARIN ERSTAD .376 06 ICHIRO SUZUKI 196 94 LARRY WALKER 65 85 WILLIE WILSON 22 54 DON MUELLER .376 58 RICHIE ASHBURN 193 99 ROBIN VENTURA 65 06 GRADY SIZEMORE 22 97 LARRY -

My Life in Baseball's Fast Lane Online

d2w0e (Free download) Rock Solid: My Life in Baseball's Fast Lane Online [d2w0e.ebook] Rock Solid: My Life in Baseball's Fast Lane Pdf Free Tim Raines, Alan Maimon ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1237736 in Books 2017-04-04 2017-04-04Format: International EditionOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.00 x .93 x 6.00l, #File Name: 1443453102272 pages | File size: 31.Mb Tim Raines, Alan Maimon : Rock Solid: My Life in Baseball's Fast Lane before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Rock Solid: My Life in Baseball's Fast Lane: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Good readBy BlairGood book about one of my all time favorite players. I was hoping for it to be better but still a good read. I would highly encourage any former Expos fans to read it. Glad he finally made it in the HOF.0 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Worth the wait!By Scott GoodaleI will admit Tim Raines was my favorite player in the 80's, so I am a bit biased here. That said, this book is a fast read. He glosses over his career without getting to deep into anything. I felt he had more to say, but wanted to cover everything, so that's what he did. His issues with cocaine were well documented in the Montreal newspapers back in the 80's, but reading about some of the details now would have added more to the story. -

* Text Features

The Boston Red Sox Saturday, April 18, 2020 * The Boston Globe Fenway Park is ready to play ball, even though we are not Stan Grossfeld The grass is perfect and the old ballpark is squeaky clean — it was scrubbed and disinfected for viral pathogens for three days in March. Spending a few hours at Fenway Park is good for the soul. The ballpark is totally silent. The mound and home plate are covered by tarps and the foul lines aren’t drawn yet, but it feels as if there still could be a game played today. The sun’s warmth reflecting off The Wall feels good. The tug of the past is all around but the future is the great unknown. In Fenway, zoom is still a word to describe a Chris Sale fastball, not a video conferencing app. Old friend Terry Francona and the Cleveland Indians would have been here this weekend and there would’ve been big hugs by the batting cage and the rhythmic crack of bat meeting ball. But now gaining access is nearly impossible and includes health questions and safety precautions and a Fenway security escort. Visitors must wear a respiratory mask, gloves, and practice social distancing, larger than the lead Dave Roberts got on Mariano Rivera in the 2004 ALCS. Carissa Unger of Green City Growers in Somerville is planting organic vegetables for Fenway Farms, located on the rooftop of the park. She is one of the few allowed into the ballpark. The harvest this year all will be donated to a local food pantry. -

1. Richie Ashburn (April 11, 1962) 60

1. Richie Ashburn (April 11, 1962) 60. Joe Hicks (July 12, 1963) 117. Dick Rusteck (June 10, 1966) 2. Felix Mantilla 61. Grover Powell (July 13, 1963) 118. Bob Shaw (June 13, 1966) 3. Charlie Neal 62. Dick Smith (July 20, 1963) 119. Bob Friend (June 18, 1966) 4. Frank Thomas 63. Duke Carmel (July 30, 1963) 120. Dallas Green (July 23, 1966) 5. Gus Bell 64. Ed Bauta (August 11, 1963) 121. Ralph Terry (August 11, 1966) 6. Gil Hodges 65. Pumpsie Green (September 4, 1963) 122. Shaun Fitzmaurice (September 9, 1966) 7. Don Zimmer 66. Steve Dillon (September 5, 1963) 123. Nolan Ryan (September 11, 1966) 8. Hobie Landrith 67. Cleon Jones (September 14, 1963) --- 9. Roger Craig --- 124. Don Cardwell (April 11, 1967) 10. Ed Bouchee 68. Amado Samuel (April 14, 1964) 125. Don Bosch 11. Bob Moorhead 69. Hawk Taylor 126. Tommy Davis 12. Herb Moford 70. John Stephenson 127. Jerry Buchek 13. Clem Labine 71. Larry Elliot (April 15, 1964) 128. Tommie Reynolds 14. Jim Marshall 72. Jack Fisher (April 17, 1964) 129. Don Shaw 15. Joe Ginsberg (April 13, 1962) 73. George Altman 130. Tom Seaver (April 13, 1967) 16. Sherman Jones 74. Jerry Hinsley (April 18, 1964) 131. Chuck Estrada 17. Elio Chacon 75. Bill Wakefield 132. Larry Stahl 18. John DeMerit 76. Ron Locke (April 23, 1964) 133. Sandy Alomar 19. Ray Daviault 77. Charley Smith (April 24, 1964) 134. Ron Taylor 20. Bobby Smith 78. Roy McMillan (May 9, 1964) 135. Jerry Koosman (April 14, 1967) 21. Chris Cannizzaro (April 14, 1962) 79. -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

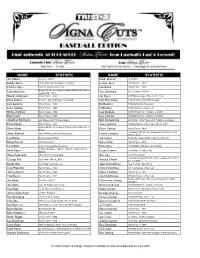

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

College Baseball Foundation January 30, 2008 Boyd, Thank You For

College Baseball Foundation P.O. Box 6507 Phone: 806-742-0301 x249 Lubbock TX 79493-6507 E-mail: [email protected] January 30, 2008 Boyd, Thank you for participating in the balloting for the College Baseball Hall of Fame’s 2008 Induction Class. We appreciate your willingness to help. In the voters packet you will find the official ballot, an example ballot, and the nominee biographies: 1. The official ballot is what you return to us. Please return to us no later than Mon- day, February 11. 2. The example ballot’s purpose is to demonstrate the balloting rules. Obviously the names on the example ballot are not the nominee names. That was done to prevent you from being biased by the rankings you see there. 3. Each nominee has a profile in the biography packet. Some are more detailed than others and reflect what we received from the institutions and/or obtained in our own research. The ballot instructions are somewhat detailed, so be sure to read the directions at the top of the official ballot. Use the example ballot as a reference. Please try to consider the nominees based on their collegiate careers. In many cases nominees have gone on to professional careers but keep the focus on his college career as a player and/or coach. The Veterans (pre-1947) nominees often lack biographical details relative to those in the post-1947 categories. In those cases, the criteria may take on a broader spectrum to include the impact they had on the game/history of college baseball, etc. -

1989 Topps Baseball Card Set Checklist

1 989 TOPPS BASEBALL CARD SET CHECKLIST 1 George Bell 2 Wade Boggs 3 Gary Carter 4 Andre Dawson 5 Orel Hershiser 6 Doug Jones 7 Kevin McReynolds 8 Dave Eiland 9 Tim Teufel 10 Andre Dawson 11 Bruce Sutter 15 Robby Thompson 16 Ron Robinson 17 Brian Downing 18 Rick Rhoden 19 Greg Gagne 20 Steve Bedrosian 21 White Sox Leaders 22 Tim Crews 23 Mike Fitzgerald 24 Larry Andersen 25 Frank White 26 Dale Mohorcic 28 Mike Moore 29 Kelly Gruber 30 Dwight Gooden 31 Terry Francona 32 Dennis Rasmussen 33 B.J. Surhoff 34 Ken Williams 36 Mitch Webster 37 Bob Stanley 38 Paul Runge 39 Mike Maddux 40 Steve Sax 41 Terry Mulholland 42 Jim Eppard 43 Guillermo Hernandez 44 Jim Snyder 45 Kal Daniels 46 Mark Portugal 47 Carney Lansford Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© 2019 1 48 Tim Burke 49 Craig Biggio 50 George Bell 51 Angels Leaders (Mark McLemore) 52 Bob Brenly 53 Ruben Sierra 54 Steve Trout 55 Julio Franco 56 Pat Tabler 58 Lee Mazzilli 59 Mark Davis 60 Tom Brunansky 61 Neil Allen 62 Alfredo Griffin 63 Mark Clear 65 Rick Reuschel 67 Dave Palmer 68 Darrell Miller 69 Jeff Ballard 70 Mark McGwire 71 Mike Boddicker 73 Pascual Perez 74 Nick Leyva 75 Tom Henke 77 Doyle Alexander 78 Jim Sundberg 79 Scott Bankhead 80 Cory Snyder 81 Expos Leaders (Tim Raines) 83 Jeff Blauser 84 Bill Bene 85 Kevin McReynolds 86 Al Nipper 87 Larry Owen 88 Darryl Hamilton 89 Dave LaPoint 90 Vince Coleman 91 Floyd Youmans 92 Jeff Kunkel 93 Ken Howell 96 Rick Cerone 97 Greg Mathews 98 Larry Sheets 99 Sherman Corbett 100 Mike Schmidt 101 Les Straker 102 Mike Gallego Compliments of BaseballCardBinders.com© -

Sports Figures Price Guide

SPORTS FIGURES PRICE GUIDE All values listed are for Mint (white jersey) .......... 16.00- David Ortiz (white jersey). 22.00- Ching-Ming Wang ........ 15 Tracy McGrady (white jrsy) 12.00- Lamar Odom (purple jersey) 16.00 Patrick Ewing .......... $12 (blue jersey) .......... 110.00 figures still in the packaging. The Jim Thome (Phillies jersey) 12.00 (gray jersey). 40.00+ Kevin Youkilis (white jersey) 22 (blue jersey) ........... 22.00- (yellow jersey) ......... 25.00 (Blue Uniform) ......... $25 (blue jersey, snow). 350.00 package must have four perfect (Indians jersey) ........ 25.00 Scott Rolen (white jersey) .. 12.00 (grey jersey) ............ 20 Dirk Nowitzki (blue jersey) 15.00- Shaquille O’Neal (red jersey) 12.00 Spud Webb ............ $12 Stephen Davis (white jersey) 20.00 corners and the blister bubble 2003 SERIES 7 (gray jersey). 18.00 Barry Zito (white jersey) ..... .10 (white jersey) .......... 25.00- (black jersey) .......... 22.00 Larry Bird ............. $15 (70th Anniversary jersey) 75.00 cannot be creased, dented, or Jim Edmonds (Angels jersey) 20.00 2005 SERIES 13 (grey jersey ............... .12 Shaquille O’Neal (yellow jrsy) 15.00 2005 SERIES 9 Julius Erving ........... $15 Jeff Garcia damaged in any way. Troy Glaus (white sleeves) . 10.00 Moises Alou (Giants jersey) 15.00 MCFARLANE MLB 21 (purple jersey) ......... 25.00 Kobe Bryant (yellow jersey) 14.00 Elgin Baylor ............ $15 (white jsy/no stripe shoes) 15.00 (red sleeves) .......... 80.00+ Randy Johnson (Yankees jsy) 17.00 Jorge Posada NY Yankees $15.00 John Stockton (white jersey) 12.00 (purple jersey) ......... 30.00 George Gervin .......... $15 (whte jsy/ed stripe shoes) 22.00 Randy Johnson (white jersey) 10.00 Pedro Martinez (Mets jersey) 12.00 Daisuke Matsuzaka .... -

Padres Press Clips Thursday, January 19, 2017

Padres Press Clips Thursday, January 19, 2017 Article Source Author Page Happily Trevor after: HOFfman eyes '18 MLB.com Cassavell 2 Hall's bells should ring for Trevor in '18 MLB.com Justice 3 Stash the party favors: Trevor Hoffman's Hall wait temporary UT San Diego Miller 6 Trevor Hoffman narrowly misses election to Hall of Fame UT San Diego Lin 8 Padres roster review: Robbie Erlin UT San Diego Sanders 10 Glenn Hoffman, Clay Kirby Next Additions to Top 100 Padres Padres.com Center 11 1 Happily Trevor after: HOFfman eyes '18 By AJ Cassavell / MLB.com | @AJCassavell | January 18th, 2017 SAN DIEGO -- Trevor Hoffman, one of the greatest relief pitchers of all time, came just shy of closing out his Hall of Fame legacy on Wednesday. In his second year on the ballot, the legendary Padres closer fell a mere five votes short of the 332 required for induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Only Jeff Bagwell, Tim Raines and Ivan Rodriguez received the 75 percent needed for enshrinement in Cooperstown on Wednesday. Hoffman ultimately finished at 74, making him only the sixth player in history to fall one percentage point shy of being voted into the Hall. "I first want to send a very heartfelt congratulations to Jeff Bagwell, Tim Raines and Ivan Rodriguez. All three men exemplify what it means to be a Hall of Famer in our game," Hoffman said in a statement. "For me, falling short of this class is disappointing, but I don't take being on the ballot lightly. -

Analyzing the Parallelism Between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2011 Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement Daniel S. Greene Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Canadian History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Greene, Daniel S., "Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement" (2011). Honors Theses. 988. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/988 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement By Daniel Greene Senior Project Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Department of History Union College June, 2011 i Greene, Daniel Analyzing the Parallelism between the Rise and Fall of Baseball in Quebec and the Quebec Secession Movement My Senior Project examines the parallelism between the movement to bring baseball to Quebec and the Quebec secession movement in Canada. Through my research I have found that both entities follow a very similar timeline with highs and lows coming around the same time in the same province; although, I have not found any direct linkage between the two. My analysis begins around 1837 and continues through present day, and by analyzing the histories of each movement demonstrates clearly that both movements followed a unique and similar timeline.