Species Status Assessment Version 1.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Manatee State Park Approved State of Florida

LAKE MANATEE STATE PARK UNIT MANAGEMENT PLAN APPROVED STATE OF FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Division of Recreation and Parks October 15, 2004 Department of Environmental Protection Marjory Stoneman Douglas Building Jeb Bush 3900 Commonwealth Boulevard, MS 140 Colleen Castille Governor Tallahassee, Florida 32399-3000 Secretary Phone: (850) 245-2784 Fax: (850) 245-2786 December 7, 2004 Ms. BryAnne White Office of Park Planning Division of Recreation and Parks 3900 Commonwealth Blvd.; M.S. 525 Tallahassee, Florida 32399 Re: Lake Manatee State Park Lease #2543 Ms. White: On October 15, 2004, the Acquisition and Restoration Council recommended approval of the Lake Manatee State Park management plan. On December 7, 2004, the Office of Environmental Services, acting as agent for the Board of Trustees of the Internal Improvement Trust Fund, approved the management plan for the Lake Manatee State Park. Pursuant to Section 253.034, Florida Statutes, and Chapter 18-2, Florida Administrative Code this plan’s ten-year update will be due on December 7, 2014. Approval of this land management plan does not waive the authority or jurisdiction of any governmental entity that may have an interest in this project. Implementation of any upland activities proposed by this management plan may require a permit or other authorization from federal and state agencies having regulatory jurisdiction over those particular activities. Pursuant to the conditions of your lease, please forward copies of all permits to this office upon issuance. Sincerely, Paula L. Allen Office of Environmental Services Division of State Lands Department of Environmental Protection "More Protection, Less Process” Printed on recycled paper. -

FLORIDA GOLDEN ASTER Chrysopsis Floridana

FLORIDA GOLDEN ASTER Chrysopsis floridana Above: Photo of Florida Golden Aster flower cluster. Photo courtesy of Laurie Markham. Left: Photo of Florida Golden Aster plant. Photo courtesy of Laurie Markham. FAMILY: Asteraceae (Aster family) STATUS: Endangered (Federal Register, May 16, 1986) DESCRIPTION AND REPRODUCTION: Young plants of this perennial herb form rosettes with leaves that are covered with dense, white, short-wooly hairs. Upright stems that grow from the rosettes are 0.3-0.4 meters (1-1.5 feet) tall, with closely-spaced, obovate-elliptic, hairy leaves. The leaves are nearly as large at the top of the stem as at the bottom. The flower heads are arranged in a more or less flat-topped cluster. Each head is slightly over 2.5 centimeters (1 inch) in diameter. Both the central disc and the rays are yellow. This plant is short-lived, and reproduces entirely by seeds. Its seeds are apparently dispersed primarily by the wind. RANGE AND POPULATION LEVEL: Florida golden aster is currently known from Hardee, Hillsborough, Manatee and Pinellas Counties, Florida. 2004 surveys on Hillsborough County lands have discovered several new populations (Cox et al. 2004). Additional survey will be conducted in 2005 on additional Hillsborough and Manatee Counties land. Systematic surveys should be continued and De Soto and Sarasota Counties should be included in this search. Historic sites include Long Key (St. Petersburg Beach) in Pinellas County, and Bradenton Beach and Bradenton in Manatee County. HABITAT: The species grows in open, sunny areas. It occurs in sand pine-evergreen oak scrub vegetation on excessively-drained fine white sand. -

Cocoa Beach Maritime Hammock Preserve Management Plan

MANAGEMENT PLAN Cocoa Beach’s Maritime Hammock Preserve City of Cocoa Beach, Florida Florida Communities Trust Project No. 03 – 035 –FF3 Adopted March 18, 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION PAGE I. Introduction ……………………………………………………………. 1 II. Purpose …………………………………………………………….……. 2 a. Future Uses ………….………………………………….…….…… 2 b. Management Objectives ………………………………………….... 2 c. Major Comprehensive Plan Directives ………………………..….... 2 III. Site Development and Improvement ………………………………… 3 a. Existing Physical Improvements ……….…………………………. 3 b. Proposed Physical Improvements…………………………………… 3 c. Wetland Buffer ………...………….………………………………… 4 d. Acknowledgment Sign …………………………………..………… 4 e. Parking ………………………….………………………………… 5 f. Stormwater Facilities …………….………………………………… 5 g. Hazard Mitigation ………………………………………………… 5 h. Permits ………………………….………………………………… 5 i. Easements, Concessions, and Leases …………………………..… 5 IV. Natural Resources ……………………………………………..……… 6 a. Natural Communities ………………………..……………………. 6 b. Listed Animal Species ………………………….…………….……. 7 c. Listed Plant Species …………………………..…………………... 8 d. Inventory of the Natural Communities ………………..………….... 10 e. Water Quality …………..………………………….…..…………... 10 f. Unique Geological Features ………………………………………. 10 g. Trail Network ………………………………….…..………..……... 10 h. Greenways ………………………………….…..……………..……. 11 i Adopted March 18, 2004 V. Resources Enhancement …………………………..…………………… 11 a. Upland Restoration ………………………..………………………. 11 b. Wetland Restoration ………………………….…………….………. 13 c. Invasive Exotic Plants …………………………..…………………... 13 d. Feral -

Parks with Campground Host and Resident Volunteer Opportunities

Parks with Campground Host and Resident Volunteer Opportunities Parks with a campground only Parks with resident host opportunities only Parks with both Park List 1. Alafia River State Park 2. Alfred B. Maclay Gardens State Park 29. Florida Caverns State Park 3. Anastasia State Park 30. Fort Clinch State Park 4. Bahia Honda State Park 31. Fort Cooper State Park 5. Bald Point State Park 32. Fort Pierce Inlet State Park 6. Big Lagoon State Park 33. Fort Zachary Taylor Historic 7. Big Shoals State Park State Park 8. Bill Baggs Cape Florida State Park 34. Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou 9. Blackwater River State Park State Park 10. Blue Spring State Park 35. Gamble Rogers Memorial SRA at 11. Caladesi Island State Park Flagler Beach (boat only) 36. Grayton Beach State Park 12. Camp Helen State Park 37. Henderson Beach State Park 13. Cayo Costa State Park (tent only) 38. Highlands Hammock State Park 14. Collier-Seminole State Park 39. Hillsborough River State Park 15. Colt Creek State Park 40. Honeymoon Island State Park 16. Curry Hammock State Park 41. Hontoon Island State Park (tent 17. Dade Battlefield Historic State Park only with no hookup & one 18. De Leon Springs State Park volunteer trailer) 19. Delnor-Wiggins Pass State Park 42. Hugh Taylor Birch State Park 20. Dr. Julian G. Bruce St. George Island 43. Ichetucknee Springs State Park State Park 44. John D. MacArthur Beach State Park 21. Dudley Farm Historic State Park 45. John Pennekamp Coral Reef 22. Econfina River State Park State Park 23. Eden Gardens State Park 46. -

FLORIDA STATE PARKS FEE SCHEDULE (Fees Are Per Day Unless Otherwise Noted) 1. Statewide Fees Admission Range $1.00**

FLORIDA STATE PARKS FEE SCHEDULE (Fees are per day unless otherwise noted) 1. Statewide Fees Admission Range $1.00** - $10.00** (Does not include buses or admission to Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park or Weeki Wachee Springs State Park) Single-Occupant Vehicle or Motorcycle Admission $4.00 - $6.00** (Includes motorcycles with one or more riders and vehicles with one occupant) Per Vehicle Admission $5.00 - $10.00** (Allows admission for 2 to 8 people per vehicle; over 8 people requires additional per person fees) Pedestrians, Bicyclists, Per Passenger Exceeding 8 Per Vehicle; Per $2.00 - $5.00** Passenger In Vehicles With Holder of Annual Individual Entrance Pass Admission Economically Disadvantaged Admission One-half of base (Must be Florida resident admission fee** and currently participating in Food Stamp Program) Bus Tour Admission $2.00** per person (Does not include Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park, or $60.00 Skyway Fishing Pier State Park, or Weeki Wachee Springs State Park) whichever is less Honor Park Admission Per Vehicle $2.00 - $10.00** Pedestrians and Bicyclists $2.00 - $5.00** Sunset Admission $4.00 - $10.00** (Per vehicle, one hour before closing) Florida National Guard Admission One-half of base (Active members, spouses, and minor children; validation required) admission fee** Children, under 6 years of age Free (All parks) Annual Entrance Pass Fee Range $20.00 - $500.00 Individual Annual Entrance Pass $60.00 (Retired U. S. military, honorably discharged veterans, active-duty $45.00 U. S. military and reservists; validation required) Family Annual Entrance Pass $120.00 (maximum of 8 people in a group; only allows up to 2 people at Ellie Schiller Homosassa Springs Wildlife State Park and Weeki Wachee Springs State Park) (Retired U. -

![Greenways Trails [EL08] 20110406 Copy.Eps](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8169/greenways-trails-el08-20110406-copy-eps-718169.webp)

Greenways Trails [EL08] 20110406 Copy.Eps

R 17 E R 18 E R 19 E R 20 E R 21 E R 22 E MULTI-USE, PAVED TRAILS Suncoast NAME MILES Air Cargo Road 1.4 G HILLSBOROUGH Al Lopez Park 3.3 BrookerBrooker CreekCreek un n CorridorCorridor Suncoast H Aldermans Ford Park 1.9 w y Trail Amberly Drive 2.8 l B LakeLake DanDan 39 Bayshore Boulevard Greenways 4.4 EquestrianEquestrian TrailTrail Lake s GREENWAYS SYSTEM F z e n Lut rn R P d w OakridgeOakridge Brandon Parkway 1.4 o EquestrianEquestrian TrailTrail HillsboroughHillsborough RRiveriver LLUTZUTZ LAKEAKE FERNF D Bruce B Downs Boulevard 4.8 BrookerBrooker CCreekreek ERN RDRD StateState ParkPark B HeadwatersHeadwaters 75 NNewew TTampaampa Y e Cheney Park 0.3 TrailTrail c A LutzLutz W u Commerce Park Boulevard 1.4 KeystoneKeystone K Tam r BlackwaterBlackwater Bruce B Downs Bl Downs B Bruce R ew pa B A N N Bl FloridaFlorida TrailTrail PPARKWAY L reek CreekCreek PreservePreserve Compton Drive 1.4 C D TrailTrail Bl E E ss Copeland Park 2.3 D K CypressCypress TATAR RRD N SUNSETSUNSET LNLN Cro O R Y P H ON GS T N A I I I O R V CreekCreek SP D G Cross County Greenway 0.8 S 275 G A R H W R H WAYNE RD A YS L R L C T 41 579 C CROOKED LN DairyDairy A O A A Cypress Point Park 1.0 N N L N KeystoneKeystone C P O D E D N LAK R FarmFarm C H D H T r Davis Island Park 0.5 U r O O R U Lake U S D SSUNCOAS 568 D A A Bo N G y S Desotto Park 0.3 co W Keystone T K u P N R I m D L E D BrookerBrooker CreekCreek t Rd 589 l RS EN R V d E VVanan DDykeyke RdRd a GRE DeadDead E Shell Point Road 1.2 Y I NNewew TampaTampa R ConeCone RanchRanch VVanan DDykeyke RRdd AV L LIVINGSTON -

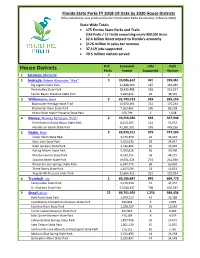

Florida State Parks Data by 2021 House District

30, Florida State Parks FY 2019-20 Data by 2021 House Districts This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation . FloridaStateParksFoundation.org Statewide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.2 billion direct impact to Florida’s economy • $150 million in sales tax revenue • 31,810 jobs supported • 25 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Salzman, Michelle 0 2 Andrade, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 31,073,188 436 349,462 Big Lagoon State Park 10,336,536 145 110,254 Perdido Key State Park 17,191,206 241 198,276 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,545,446 50 40,932 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 26,651,285 416 362,492 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 18,971,114 266 218,287 Blackwater River State Park 7,101,563 99 78,680 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 578,608 51 65,525 4 Maney, Thomas Patterson “Patt” 2 41,626,278 583 469,477 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 7,558,966 106 83,636 Henderson Beach State Park 34,067,312 477 385,841 5 Drake, Brad 9 64,140,859 897 696,022 Camp Helen State Park 3,133,710 44 32,773 Deer Lake State Park 1,738,073 24 19,557 Eden Gardens State Park 3,235,182 45 36,128 Falling Waters State Park 5,510,029 77 58,866 Florida Caverns State Park 4,090,576 57 39,405 Grayton Beach State Park 17,072,108 239 186,686 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 6,911,495 97 78,277 Three Rivers State Park 2,916,005 41 30,637 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 19,533,681 273 213,693 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 45,103,015 632 504,860 Camp Helen State Park 3,133,710 44 32,773 St. -

RV Sites in the United States Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile

RV sites in the United States This GPS POI file is available here: https://poidirectory.com/poifiles/united_states/accommodation/RV_MH-US.html Location Map 110-Mile Park Map 35 Mile Camp Map 370 Lakeside Park Map 5 Star RV Map 566 Piney Creek Horse Camp Map 7 Oaks RV Park Map 8th and Bridge RV Map A AAA RV Map A and A Mesa Verde RV Map A H Hogue Map A H Stephens Historic Park Map A J Jolly County Park Map A Mountain Top RV Map A-Bar-A RV/CG Map A. W. Jack Morgan County Par Map A.W. Marion State Park Map Abbeville RV Park Map Abbott Map Abbott Creek (Abbott Butte) Map Abilene State Park Map Abita Springs RV Resort (Oce Map Abram Rutt City Park Map Acadia National Parks Map Acadiana Park Map Ace RV Park Map Ackerman Map Ackley Creek Co Park Map Ackley Lake State Park Map Acorn East Map Acorn Valley Map Acorn West Map Ada Lake Map Adam County Fairgrounds Map Adams City CG Map Adams County Regional Park Map Adams Fork Map Page 1 Location Map Adams Grove Map Adelaide Map Adirondack Gateway Campgroun Map Admiralty RV and Resort Map Adolph Thomae Jr. County Par Map Adrian City CG Map Aerie Crag Map Aeroplane Mesa Map Afton Canyon Map Afton Landing Map Agate Beach Map Agnew Meadows Map Agricenter RV Park Map Agua Caliente County Park Map Agua Piedra Map Aguirre Spring Map Ahart Map Ahtanum State Forest Map Aiken State Park Map Aikens Creek West Map Ainsworth State Park Map Airplane Flat Map Airport Flat Map Airport Lake Park Map Airport Park Map Aitkin Co Campground Map Ajax Country Livin' I-49 RV Map Ajo Arena Map Ajo Community Golf Course Map -

Florida Golden Aster Chrysopsis (=Heterotheca) Floridana Small

Florida Golden Aster Chrysopsis (=Heterotheca) floridana Small he Florida golden aster is a perennial herb in the Federal Status: Endangered (May 16, 1986) aster family with a distribution limited to a few Critical Habitat: None Designated Tcounties in west-central Florida. The Florida golden Florida Status: Endangered aster occurs in sand pine and oak scrub or in disturbed areas at the edges of scrub. Recovery Plan Status: Contribution (May 1999) This account represents South Floridas contribution to Geographic Coverage: South Florida the existing recovery plan for the Florida golden aster (FWS 1988). Figure 1. County distribution of the Florida golden aster. Description Chrysopsis floridana is a perennial herb with stems that are woody toward the base and non-woody above. The plants have basal rosettes (clusters of leaves at ground level) with leaves 4 to 10 cm long, 1.5 to 2.0 cm wide; the leaves of the rosette are densely short-wooly pubescent. The stem leaves are nearly the same size from the top to the bottom of the stem; they are obovate-elliptic, slightly clasping the stem, entire, and densely short-wooly pubescent. The flower heads are grouped into a more or less flat-topped cluster of 1 to 25 heads at the top of the stem. Each head is slightly over 2.5 cm in diameter. Both the central disc and the rays are golden yellow. C. floridana is distinguished from other members of its genus by its perennial habit, the woodiness of its stems, the wooliness and the shape of the stem and the leaves, and the way the flower heads are arranged in a flat-topped cluster (Semple 1981, Wunderlin et al. -

Suncoast Grapevine

www.ficus.usf.edu/orgs/suncoastwww.suncoastnps.org The Suncoast Grapevine Newsletter of the Suncoast Native Plant Society, Inc. Volume 28 Number 5 May 2011 Chrysopsis floridana Restoration Efforts: Bok Tower Gardens, a National Historic Landmark Presented by Cindy Campbell Wednesday, May 18 @ 7pm Hillsborough County Extension Service Ms. Cindy Campbell will be talking about the work her team at Bok Tower Gardens has done reintroducing one of the most interesting rare endemics that is found right here in central Florida, Chrysopsis floridana. This native plant is a beautiful aster with frosty white hairs on its foliage that gives it protection from the harsh conditions of the white sand scrubs it is found in. While working at Bok Tower Gardens , Cindy has learned very much about the growing characteristics of Chrysopsis floridana as well as many other species of endangered plants in Florida. Her team has pioneered many growing techniques and plant reestablishment techniques of rare plants. Her work will ensure that the population of these beautiful plants will continue to improve. Cindy organized efforts along with our Suncoast chapter and numerous other groups to plant over 1,000 Chrysopsis floridana plants at SWFWMD’s Southfork Tract in Manatee County. Later, our chapter participated in monitoring the condition of the restoration. Detailed data of health, failure rate, and size were recorded. This monitoring program is to continue for five years. Cindy is currently the rare plant curator at Bok Tower Gardens in Lake Wales. Previously, she has worked at the Disney Preserve and at The Nature Conservancy Preserve in Kentucky. -

State and Federally Listed Species for Hillsborough County

State and Federally Listed Species for Hillsborough County - Note: Only federally listed plant species are included; “=”means a.k.a.; “SA” means similarity of appearance Scientific Name Common Name State USFWS Habitats Used Amphibians Rana capito Gopher (=crawfish) frog Sp. Spec. Concern Longleaf Pine/Turkey Oak Hills, Sand Pine Scrub, Scrubby Flatwoods, Xeric Oak Hammock (uses ephemeral wetlands for breeding) Birds Aphelocoma coerulescens Florida scrub-jay Threatened Threatened Sand Pine Scrub and Scrubby Flatwoods Aramus guarauna Limpkin Sp. Spec. Concern Mangrove Swamp, Freshwater Marsh & Ponds, Cypress Swamp, Springs, Slough, Sawgrass Marsh, Ruderal (impoundments, canals, sugarcane, etc.) Athene cunicularia floridana Florida burrowing owl Sp. Spec. Concern N. & S. FL Flatwoods (dry prairie or grassland habitat), Ruderal (primarily pasture) Charadrius alexandrinus Southeastern snowy plover Threatened N. & S. FL Coastal Strand (west coast only) tenuirostris Charadrius melodus Piping plover Threatened Threatened N. & S. FL Coastal Stand, Nearshore Reef Egretta caerulea Little blue heron Sp. Spec. Concern N. & S. FL Coastal Strand, Wet Prairie or Slough, Freshwater Marsh & Ponds, Mangrove Swamps, Cypress Swamp, Sawgrass Marsh, Salt Marsh, Shrub Bog & Bay Swamp, Ruderal Egretta rufescens Reddish egret Sp. Spec. Concern Mangrove Swamp, N. & S. FL Coastal Strand, Salt Marsh Egretta thula Snowy egret Sp. Spec. Concern N. & S. FL Coastal Strand, Wet Prairie or Slough, Freshwater Marsh & Ponds, Mangrove Swamps, Cypress Swamp, Sawgrass Marsh, Salt Marsh, Shrub Bog & Bay Swamp, Ruderal Egretta tricolor Tricolored (=Louisiana) heron Sp. Spec. Concern N. & S. FL Coastal Strand, Wet Prairie or Slough, Freshwater Marsh & Ponds, Mangrove Swamps, Cypress Swamp, Sawgrass Marsh, Salt Marsh, Shrub Bog & Bay Swamp, Ruderal Eudocimus albus White ibis Sp. -

30, House Districts

30, Florida State Parks FY 2018-19 Data by 2020 House Districts (This compilation was produced by the Florida State Parks Foundation, February 2020) . State Wide Totals • 175 Florida State Parks and Trails (164 Parks / 11 Trails) comprising nearly 800,000 Acres • $2.6 billion direct impact to Florida’s economy • $176 million in sales tax revenue • 37,119 jobs supported • 29.5 million visitors served # of Economic Jobs Park House Districts Parks Impact Supported Visitors 1 Salzman, Michelle 0 2 Andrade, Robert Alexander “Alex” 3 35,086,662 491 399,461 Big Lagoon State Park 13,388,360 187 146,049 Perdido Key State Park 18,435,488 258 215,257 Tarklin Bayou Preserve State Park 3,262,814 46 38,155 3 Williamson, Jayer 3 22,793,752 319 262,150 Blackwater Heritage State Trail 15,070,491 211 175,244 Blackwater River State Park 7,562,462 106 85,258 Yellow River Marsh Preserve State Park 160,799 2 1,648 4 Maney, Thomas Patterson “Patt” 2 49,456,096 692 567,948 Fred Gannon Rocky Bayou State Park 8,154,105 114 91,652 Henderson Beach State Park 41,301,991 578 476,296 5 Drake, Brad 9 69,939,012 979 747,560 Camp Helen State Park 3,176,350 44 34,444 Deer Lake State Park 2,102,533 29 24,057 Eden Gardens State Park 3,186,404 45 35,924 Falling Waters State Park 5,760,818 81 59,390 Florida Caverns State Park 4,532,155 63 44,215 Grayton Beach State Park 19,551,524 274 212,050 Ponce de Leon Springs State Park 6,347,774 89 69,063 Three Rivers State Park 1,617,039 23 15,653 Topsail Hill Preserve State Park 23,664,415 331 252,764 6 Trumbull, Jay 2 60,186,687 842 684,779 Camp Helen State Park 3,176,350 44 34,444 St.