Social Acceptance Project for Family Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAMBULI Weekly Newsletter the Official E-Newsletter of the Federation of Philippine Industries Volume 18 Issue No

aoa TAMBULI Weekly Newsletter The Official e-Newsletter of the Federation of Philippine Industries Volume 18 Issue No. 33 05 September 2014 ______________________________________________________________________________ 2014 Bayabay Media and Sustainable Development awardees feted during the FPI General Membership Meeting; MOA signed The Federation of Philippine Industries (FPI) successfully held its 2014 General Membership Meeting (GMM) last Wednesday, September 03, 2014 at the Grand Ballroom Hotel InterContinental, Makati City. The 2014-2016 FPI Directors and Officers were inducted by the Bureau of Customs Com. John Philip Sevilla who was also introduced by EVP Jesus Montemayor as the keynote speaker. Com. Sevilla presented the actions and changes that they have instituted in the Bureau of Customs which was roundly applauded by the delegates composed of senior executives coming from the Federation’s 34 industry association and 110 corporation members. The GMM was jumpstarted by the discussion of the current serious concerns and challenges that are facing the manufacturing industries particularly on anti-smuggling, environment and power & energy. Chairman Jesus Lim Arranza updated the members of the various actions which the Federation made on anti-smuggling which is the flagship advocacy of the FPI, while Director Peter Quintana and Mr. Emmanuel Go discussed the concerns and challenges of the manufacturing industries on environment and power & energy, respectively. President George S. Chua made an annual report of the other activities of the Federation. Bayabay Media Award FPI Chairman Arranza and the FPI Board conferred the 2014 Annual FPI Bayabay Award to honor outstanding and deserving media practitioners who have raised important and sensitive issues that have serious impact on our country, - by consistently and conscientiously educating the masses in a clear, equitable, and balanced manner, which is a basic tenet required to ensure the preservation of our vibrant democratic country. -

The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Social Ethics Society Journal of Applied Philosophy Special Issue, December 2018, pp. 181-206 The Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) and ABS-CBN through the Prisms of Herman and Chomsky’s “Propaganda Model”: Duterte’s Tirade against the Media and vice versa Menelito P. Mansueto Colegio de San Juan de Letran [email protected] Jeresa May C. Ochave Ateneo de Davao University [email protected] Abstract This paper is an attempt to localize Herman and Chomsky’s analysis of the commercial media and use this concept to fit in the Philippine media climate. Through the propaganda model, they introduced the five interrelated media filters which made possible the “manufacture of consent.” By consent, Herman and Chomsky meant that the mass communication media can be a powerful tool to manufacture ideology and to influence a wider public to believe in a capitalistic propaganda. Thus, they call their theory the “propaganda model” referring to the capitalist media structure and its underlying political function. Herman and Chomsky’s analysis has been centered upon the US media, however, they also believed that the model is also true in other parts of the world as the media conglomeration is also found all around the globe. In the Philippines, media conglomeration is not an alien concept especially in the presence of a giant media outlet, such as, ABS-CBN. In this essay, the authors claim that the propaganda model is also observed even in the less obvious corporate media in the country, disguised as an independent media entity but like a chameleon, it © 2018 Menelito P. -

Philippines Page 1 of 25

2008 Human Rights Report: Philippines Page 1 of 25 2008 Human Rights Report: Philippines BUREAU OF DEMOCRACY, HUMAN RIGHTS, AND LABOR 2008 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices February 25, 2009 The Philippines, with a population of 89 million, is a multiparty republic with an elected president and bicameral legislature. In May 2007 approximately 73 percent of registered citizens voted in mid-term elections for both houses of congress and provincial and local governments. The election generally was free and fair but was marred by violence and allegations of vote buying and electoral fraud. Long-running Communist and Muslim insurgencies affected the country. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control of the security forces; however, there were some instances in which elements of the security forces acted independently. Arbitrary, unlawful, and extrajudicial killings by elements of the security services and political killings, including killings of journalists, by a variety of actors continued to be major problems. In recent years, following increased domestic and international scrutiny, reforms were undertaken and the number of killings and disappearances dropped dramatically. Concerns about impunity persisted. Members of the security services committed acts of physical and psychological abuse on suspects and detainees, and there were instances of torture. Prisoners awaiting trial and those already convicted were often held under primitive conditions. Disappearances occurred, and arbitrary or warrantless arrests and detentions were common. Trials were delayed, and procedures were prolonged. Corruption was a problem throughout the criminal justice system. Leftwing and human rights activists often were subject to harassment by local security forces. Problems such as violence against women, abuse of children, child prostitution, trafficking in persons, child labor, and ineffective enforcement of worker rights were common. -

Lopez Group Reiterates CSR Commitment At

Dec. 08-Jan. 09 Available online at www.benpres-holdings.com Christmas greetings from OML, MML and EL3 ...p. 5 Int’l banks show Lopez Group reiterates CSR commitment support for First at Clinton Global Initiative Meeting Gen, First Gas...p. 3 CHAIRMAN Oscar M. Lopez (OML) reiterated the Chairman Lopez and daughter Rina Lopez Group’s commitment to pursue corporate social receive the CGI Certificate of responsibility (CSR) projects that will improve the lives Acknowledgment presented by former of the marginalized, especially in causes for the environ- US President Clinton to Knowledge ment and education. Channel. He announced twin donations worth almost P420 million as the group’s “Commitment to Action” during the first Clinton Global Initiative (CGI) Asia Meeting in Hong Kong in early December. At the same time, the Knowledge Channel Foundation Inc. (KCFI) headed by Rina Lopez-Bautista was one of the six models of commitments presented by former US President Bill Clinton at the closing ceremonies of the CGI meet. Knowledge Channel received the highest commenda- tions from the former US President for its pioneering efforts to provide poor and marginalized but bright chil- dren in far-flung areas in the country free access to com- puter/Internet education. Clinton said the KCFI program should be replicated elsewhere in the world. “I would like to compliment them for what they’re doing A look back at 2008…p. 5 and for others to replicate this in their countries,” he said. Turn to page 7 PHOTO: ROSAN CRUZ ABS-CBN goes beyond TV WHO would have thought, back in Only a year later, in 1958, ABS- the mid-1950s, that a couple of fledg- CBN rolled out what would be the ing radio stations and a TV network first of many innovations under Don under the leadership of a man not Ening and his son Eugenio “Geny” yet 30 years old would grow into the Lopez Jr., then 28, who was tasked country’s largest media conglomerate? to run the company: the country’s ABS-CBN Broadcasting Corp. -

The Sources of the Abu Sayyaf's Resilience in the Southern

MAY 2010 . VOL 3 . ISSUE 5 A number of conclusions can be drawn The Sources of the Abu the creation of AHAI in 1989 to pursue from this incident. The kidnappings Jihad Fi Sabilillah, defined as “fighting and and Khwaja’s subsequent execution Sayyaf’s Resilience in the dying for the cause of Islam.”2 Yet it show the generational change among Southern Philippines was only in 1993 when AHAI formally militants in Pakistan and the evolving organized with Abdurajak as the amir.3 relationship between the ISI and By Rommel C. Banlaoi Taliban fighters. Khwaja, for example, Since the formal launch of AHAI in was a controversial figure due to his since the launching of the global war 1989, Abdurajak delivered several associations with the ISI and links with on terrorism in the aftermath of the khutbahs or sermons and released several certain militant groups. After he retired September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks on fatawa using the nom-de-guerre “Abu from the military, he worked as a lawyer the United States, the Philippines has Sayyaf,” in honor of Afghan resistance and defended suspected militants been engaged in a prolonged military fighter Abdul Rasul Sayyaf.4 While and Islamist politicians.17 He even campaign against the Abu Sayyaf Group Abdurajak idolized this Afghan leader, reportedly once maintained contacts (ASG). Key ASG leaders have been the suggestion that Abdurajak was an with Usama bin Ladin. It appears that killed in this battle, while others have Afghan war veteran is still a subject the Asian Tigers killed him as revenge been imprisoned for various crimes for verification.5 Some living Filipino against the ISI and against the jihadist associated with terrorism. -

THE SOCIAL MEDIA (R)EVOLUTION? Asian Perspectives on New Media

THE SOCIAL MEDIA (R)EVOLUTION? Asian Perspectives On New Media CONTRIBUTIONS BY: APOSTOL, AVASADANOND, BHADURI, NAZAKAT, PUNG, SOM, TAM, TORRES, UTAMA, VILLANUEVA, YAP EDITED BY: SIMON WINKELMANN Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Singapore Media Programme Asia The Social Media (R)evolution? Asian Perspectives On New Media Edited by Simon Winkelmann Copyright © 2012 by the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Singapore Publisher Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung 34 Bukit Pasoh Road Singapore 089848 Tel: +65 6603 6181 Fax: +65 6603 6180 Email: [email protected] www.kas.de/medien-asien/en/ All rights reserved Requests for review copies and other enquiries concerning this publication are to be sent to the publisher. The responsibility for facts, opinions and cross references to external sources in this publication rests exclusively with the contributors and their interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Layout and Design Hotfusion 7 Kallang Place #04-02 Singapore 339153 www.hotfusion.com.sg CONTENTS Foreword 5 Ratana Som Evolution Or Revolution - 11 Social Media In Cambodian Newsrooms Edi Utama The Other Side Of Social Media: Indonesia’s Experience 23 Anisha Bhaduri Paper Chase – Information Technology Powerhouse 35 Still Prefers Newsprint Sherrie Ann Torres “Philippine’s Television Network War Going Online – 47 Is The Filipino Audience Ready To Do The Click?” Engelbert Apostol Maximising Social Media 65 Bruce Avasadanond Making Money From Social Media: Cases From Thailand 87 KY Pung Social Media: Engaging Audiences – A Malaysian Perspective 99 Susan Tam Social Media - A Cash Cow Or Communication Tool? 113 Malaysian Impressions Syed Nazakat Social Media And Investigative Journalism 127 Karen Yap China’s Social Media Revolution: Control 2.0 139 Michael Josh Villanueva Issues In Social Media 151 Social Media In TV News: The Philippine Landscape 163 Social Media For Social Change 175 About the Authors 183 Foreword ithin the last few years, social media has radically changed the media Wsphere as we know it. -

Journalism Under Pressure: a Mapping of Editorial Policies and Practices for Journalists Covering Conflict

Journalism under Pressure: A mapping of editorial policies and practices for journalists covering conflict Edited by Marte Høiby and Rune Ottosen CC-BY-SA Høgskolen i Oslo og Akershus HiOA Rapport 2015 nr 6 ISSN 1892-9648 ISBN 978-82-93208-93-8 Opplag trykkes etter behov, aldri utsolgt HiOA, Læringssenter og bibliotek, Skriftserien St. Olavs plass 4, 0130 Oslo, Telefon (47) 64 84 90 00 Postadresse: Postboks 4, St. Olavs plass 0130 Oslo Adresse hjemmeside: http://www.hioa.no/Om-HiOA/Nettbokhandel For elektronisk bestilling klikk Bestille bøker Trykket hos Allkopi Trykket på Multilaser 80 g hvit 2 Preface This report concludes the findings of a survey among journalists and editors in seven countries about issues related to safety and working conditions in conflict areas. The project was funded by the Norwegian UNESCO Commission and we wish to thank the commission for the opportunity to work with this important topic. Every day we hear reports in the news about journalists killed or harassed. Safe working conditions are necessary so that reporters can get access to events and sources, and a pre- condition for doing their jobs and giving the audience and decision makers first-hand knowledge of what is happening at the scene of important events. As the pressure on journalists is a global issue, we have included seven countries on four continents in this study. An interesting part of this report is the comparison of the situation for journalists in diverse countries and, obviously, we find similarities and differences. Violence and threats against journalists are a global phenomenon, even though Norwegian journalists, for instance, generally have safer working conditions than do their colleagues in the Philippines. -

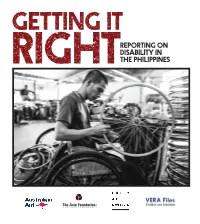

Getting It Right: Reporting on Disability in the Philippines

GettinG it reporting on disability in riGhtthe Philippines GettinG it riGhtGettinG it reporting on disability in riGht the Philippines reporting on disabilities in the Philippines GettinG it reporting on disability in riGht the Philippines Copyright ©2015 VERA Files Incorporated Quezon City, Philippines http://verafiles.org All rights reserved. No part of this manual may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review. The Asia Foundation and Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade reserve a royalty-free, nonexclusive, and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use, and to authorize others to use, the materials for the Foundation’s or Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade’s purposes. Inquiries should be addressed to The Asia Foundation, 33rd Floor, One San Miguel Avenue Building, San Miguel Avenue corner Shaw Boulevard, Ortigas Center, Pasig City, 1603 Philippines. Email: country.philippines. [email protected] This publication is made possible by the generous support of the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. The contents are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade or The Asia Foundation. The Asia Foundation is a nonprofit international development organization committed to improving lives across a dynamic and developing Asia. Informed by six decades of experience and deep local expertise, our programs address critical issues affecting Asia in the 21st century—governance and law, economic development, women’s empowerment, environment, and regional cooperation. -

TMC Is Interim Operator

February 2008 The Manila Chronicle, home to the country’s best journalists “A classic case of the intersection of media power and political power in the Philippines” Catch the pre-launch special price Now available at the Lopez Memorial Museum Available online at www.benpres-holdings.com See story on page 9 First Gen gains SCTEX to open 100% ownership in Red Vulcan ... page 2 TMC is interim operator AFTER making its name from its suc- The interim contract is good for six P21 billion project to the joint venture cessful operations of the North Luzon months and can be renewed for anoth- of TMC, First Philippine Holdings Expressway (NLEX), Tollways Man- er six months. SCTEX concessionaire Corporations (FPHC), and Egis Road agement Corporation (TMC) is now Bases Conversion and Development Operation (ERO). TMC is primarily the new operator of the 94-km Subic- Authority (BCDA) awarded the opera- engaged with the operations and main- Clark-Tarlac Expressway (SCTEX). tion and maintenance (O&M) of this Turn to page 6 Witnesses expose tampered TV ratings ... page 3 2008 ayon kay OML Taon ng mga CFOs TINAGURIANG “taon ng mga CFOs Sa kanyang taunang pambungad o chief financial officers” ni Lopez na pananalita sa mga senior executives Group chairman Chairman Oscar M. ng Lopez Group of companies, sinabi ni Lopez (OML) ang taong 2008 dahil sa OML na umaasa siyang mareresolba na mga hamong takdang harapin ng mga ang mga isyu ukol sa debt restructuring finance executives ng grupo. sa madaling panahon. Check out Power Una sa listahan ng mga kailan- “During the past year (2007), An- gang gawin ngayong bagong taon ang gel Ong (pangulo ng Benpres) and his Plant Mall finds this pagtatapos ng financial restructuring ng staff have done a commendable job Valentine’s .. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 Financial Highlights 4 Message of the Chairman 6 Financial Review 8 A Kapamilya Nation 16 Management’s Responsibility for Financial Statements 17 Report of Independent Auditors 18 Financial Statements Balance Sheets Statements of Income Statements of Changes in Stockholders’ Equity Statements of Cash Flows Notes to Financial Statements 68 Board of Directors 70 Management Committee 72 Awards and Recognition 73 List of Officers 77 Corporate Addresses 79 Banks and Other Financial Institutions AR 2006.indd 1 4/24/07 8:10:44 AM FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS AR 2006.indd 2-3 4/24/07 8:10:49 AM AR 2006.indd 4-5 4/24/07 8:11:09 AM Operating expenses, which consist of production cost, general and administrative Non-cash operating expenses, composed primarily of depreciation and expenses, cost of sales and services, and agency commission declined by 2% amortization, went down by 14% to P2,075 million in 2006 from P2,407 million to P15,724 million in 2006. Cash operating expenses were flat while non-cash in the same period last year. Bulk of the decline can be attributed to lower operating expenses declined by 14% YoY. If we strip-out the non-recurring charges, amortization costs which dropped by 23% to P904 million as the Company already Management Discussion and Analysis of Financial Condition and Results of total opex went up by 5% to P15,257 million. completed the amortization of deferred subsidies on the decoder boxes of existing Operations for 2006 US DTH subscribers in 2005. Amortization of program rights, on the other hand, Production cost was almost flat YoY at P5,714 million. -

KABALITA Resilience of a Free Press in All Platforms Is Integral to the Free Flow of Information in the Wake of the Global Pandemic

ISSUE NO. 3872 JUNE 17, 2021 KABALITA Resilience of a free press in all platforms is integral to the free flow of information in the wake of the global pandemic. While many have withered under the pandemic storm, there are media entities that continue to hold fort in the name of fearless reporting. This is the essence of love of country where freedom of the press reigns supreme, a recognition that serves as a lasting legacy. Indeed, when the newsmakers make the news, they make history. www.rcmanila.org TABLE OF CONTENTS PROGRAM TIMETABLE 03 MANILA ROTARIAN IN FOCUS 48 STAR Rtn. Teddy Kalaw, IV THE HISTORY OF THE ROTARY 06 CLUB OF MANILA BASIC EDUCATION AND JOURNALISM AWARDS 55 LITERACY 27 PRESIDENT'S CORNER COMMUNITY ECONOMIC Robert “Bobby” Lim Joseph, Jr. 57 DEVELOPMENT 28 THE WEEK THAT WAS 58 INTERNATIONAL SERVICE CLUB ADMINISTRATION 32 From the Programs Committee 60 INTERCLUB RELATIONS Programs Committee Holds Meeting Attendance THE ROTARY FOUNDATION List of Those Who Have Paid Their 62 Annual Dues Know your Rotary Club of Manila ROTARY INFORMATION Constitution, By-Laws and Policies 63 Rotary Youth Leadership Awards Board of Directors of the Rotary Club of Manila for RY 2020-2021 Holds 25th Special Meeting 65 OTHER MATTERS Board of Directors of the Rotary Club Quotes on Life by PP Frank Evaristo of Manila for RY 2021-2022 Holds Second Planning Meeting 66 ROTARY CLUB OF MANILA BOARD OF DIRECTORS AND RCMANILA FOUNDATION, INC. EXECUTIVE OFFICERS, 39 RY 2020-2021 40 VOCATIONAL SERVICE RCM BALITA EDITORIAL TEAM, RY 2020-2021 46 COGS IN THE WHEEL Rotary Club of Manila Newsletter balita June 17, 2021 02 Zoom Weekly Membership Luncheon Meeting Pro Patria Journalism Awards 2021 Rotary Year 2020-2021 Thursday, June 17, 2021, 12:30 PM PROGRAM TIMETABLE 11:30 AM Registration and Zoom In Program Moderator/Facilitator/ChikaTalk Rtn. -

Sexual Violence Against Journalists in Conflict Zones Gendered Practices and Cultures in the Newsroom

4. Sexual Violence against Journalists in Conflict Zones Gendered Practices and Cultures in the Newsroom Marte Høiby Abstract While sexual violence is a threat to both men and women in war and conflict, cases con- cerning male victims are largely absent from public discussion and women’s vulnerability regularly assumed. This paper suggests that procedures for journalist safety are influenced by a male-aggressor/female-victim paradigm, underestimating the vulnerability of male colleagues and discriminating against women. Keywords: conflict reporting, journalist safety, gender, women, sexual violence, male- aggressor female-victim paradigm Introduction While sexual violence is a threat to both men and women in war and conflict, cases concerning male victims are largely absent in the public discussion, and women’s vulnerability is regularly assumed. This chapter suggests that gendered policies and practices for journalists’ safety in the field of conflict reporting are influenced by a male aggressor/female victim paradigm, underestimating the vulnerability of male colleagues and discriminating against women. The result is limited professional leeway for female staff and underreporting of assaults for both men and women. Dominant masculinities in editorial leadership exist and influence decision making and routines, regardless of gender participation. Sexualised violence or threats against women journalists have in several cases led to sexist deployment to work in areas where female reporters have endured sexual assaults. The women journalists interviewed or otherwise considered for this study express a need to reclaim their professional freedom with respect to safety and sexual violence. Their concern is for the discrimination (misjudgement and distrust) they suffer when it comes to decision making for their own safety, and the gendered preju- Høiby, Marte (2016).