Tourism and the Soviet Past in the Baltic States

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City Break 100 Free Offers & Discounts for Exploring Tallinn!

City Break 100 free offers & discounts for exploring Tallinn! Tallinn Card is your all-in-one ticket to the very best the city has to offer. Accepted in 100 locations, the card presents a simple, cost-effective way to explore Tallinn on your own, choosing the sights that interest you most. Tips to save money with Tallinn Card Sample visits with Normal 48 h 48 h Tallinn Card Adult Tallinn Price Card 48-hour Tallinn Card - €32 FREE 1st Day • Admission to 40 top city attractions, including: Sightseeing tour € 20 € 0 – Museums Seaplane Harbour (Lennusadam) € 10 € 0 – Churches, towers and town wall – Tallinn Zoo and Tallinn Botanic Garden Kiek in de Kök and Bastion Tunnels € 8,30 € 0 – Tallinn TV Tower and Seaplane Harbour National Opera Estonia -15% € 18 € 15,30 (Lennusadam) • Unlimited use of public transport 2nd Day • One city sightseeing tour of your choice Tallinn TV Tower € 7 € 0 • Ice skating in Old Town • Bicycle and boat rental Estonian Open Air Museum with free audioguide € 15,59 € 0 • Bowling or billiards Tallinn Zoo € 5,80 € 0 • Entrance to one of Tallinn’s most popular Public transport (Day card) € 3 € 0 nightclubs • All-inclusive guidebook with city maps Bowling € 18 € 0 Total cost € 105,69 € 47,30 DISCOUNTS ON *Additional discounts in restaurants, cafés and shops plus 130-page Tallinn Card guidebook • Sightseeing tours in Tallinn and on Tallinn Bay • Day trips to Lahemaa National Park, The Tallinn Card is sold at: the Tallinn Tourist Information Centre Naissaare and Prangli islands (Niguliste 2), hotels, the airport, the railway station, on Tallinn-Moscow • Food and drink in restaurants, bars and cafés and Tallinn-St. -

Tallinn Travel Guide

TALLINN TRAVEL GUIDE FIREFLIES TRAVEL GUIDES TALLINN Steeped in Medieval charm, yet always on the cutting- edge of modernity, Tallinn offers today’s travelers plenty to see. The city is big enough and interesting enough to explore for days, but also small and compact enough to give you the full Tallinn experience in just a few hours. DESTINATION: TALLINN 1 TALLINN TRAVEL GUIDE Kids of all ages, from toddlers to teens, will love ACTIVITIES making a splash in Tallinn’s largest indoor water park, conveniently located at the edge of Old Town. Visitors can get their thrills on the three water slides, work out on the full length pool or have a quieter time in the bubble-baths, saunas and kids’ pool. The water park also has a stylish gym offering various training classes including water aerobics. Aia 18 +372 649 3370 www.kalevspa.ee Mon-Fri 6.45-21.30, Sat-Sun 8.00-21.30 If your idea of the perfect getaway involves whacking a ball with a racquet, taking a few laps at MÄNNIKU SAFARI CENTRE high speed or battling your friends with lasers, The Safari Centre lets groups explore the wilds of then Tallinn is definitely the place to be. Estonia on all-terrain quad bikes. Groups of four to 14 people can go on guided trekking adventures There are sorts of places to get your pulse rate up, that last anywhere from a few hours to an entire from health and tennis clubs to skating rinks to weekend. Trips of up to 10 days are even available. -

PERSONAL MEMORIES of the FATE of the FAMILY of 1939 ESTONIAN PRESIDENT PÄTS Helgi-Alice Päts Was Daughter-In-Law of Konstantin

PERSONAL MEMORIES OF THE FATE OF THE FAMILY OF 1939 ESTONIAN PRESIDENT PÄTS Helgi-Alice Päts was daughter-in-law of Konstantin Päts, President of the Republic of Estonia when the Red Army came in and occupied the nation. Below is her chronicle of the ordeal that Päts and his family endured. The Reminiscences of Helgi-Alice Päts For many years I have thought that I should write down what happened to my family in 1940, for it reflects at the same time what happened to the Estonian people. I dedicate these pages to my older son and to his children, Madis, who is now seventeen years old, and to Madli, who is fifteen. My younger son, Henn, died at the age of seven of starvation at the Ufa orphanage either on February 1 or 7, 1944. The exact date is not known. JULY 30, 1940. It was a cool, rainy day. In the evening, about 7 o'clock, cars roared into the yard of Kloostrimetsa farm which had been developed by Konstantin Päts at the formerly named Ussisoo as a model farm. Maxim Unt, the Interior Minister at the time, and four men emerged from the cars and came into the house. Some of them remained standing by the door and one, quite naturally, sat by the phone. Unt wanted to speak privately with Konstantin Päts and my husband, Victor. They went to talk on the closed-in porch. In connection with this event, I remember a conversation with Konstantin Päts about a week before this date. He said that we might have to go to Russia for a while. -

Travel Guide

TRAVEL GUIDE Traces of the COLD WAR PERIOD The Countries around THE BALTIC SEA Johannes Bach Rasmussen 1 Traces of the Cold War Period: Military Installations and Towns, Prisons, Partisan Bunkers Travel Guide. Traces of the Cold War Period The Countries around the Baltic Sea TemaNord 2010:574 © Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen 2010 ISBN 978-92-893-2121-1 Print: Arco Grafisk A/S, Skive Layout: Eva Ahnoff, Morten Kjærgaard Maps and drawings: Arne Erik Larsen Copies: 1500 Printed on environmentally friendly paper. This publication can be ordered on www.norden.org/order. Other Nordic publications are available at www.norden.org/ publications Printed in Denmark T R 8 Y 1 K 6 S 1- AG NR. 54 The book is produced in cooperation between Øhavsmuseet and The Baltic Initiative and Network. Øhavsmuseet (The Archipelago Museum) Department Langelands Museum Jens Winthers Vej 12, 5900 Rudkøbing, Denmark. Phone: +45 63 51 63 00 E-mail: [email protected] The Baltic Initiative and Network Att. Johannes Bach Rasmussen Møllegade 20, 2200 Copenhagen N, Denmark. Phone: +45 35 36 05 59. Mobile: +45 30 25 05 59 E-mail: [email protected] Top: The Museum of the Barricades of 1991, Riga, Latvia. From the Days of the Barricades in 1991 when people in the newly independent country tried to defend key institutions from attack from Soviet military and security forces. Middle: The Anna Akhmatova Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Handwritten bark book with Akhmatova’s lyrics. Made by a GULAG prisoner, wife of an executed “enemy of the people”. Bottom: The Museum of Genocide Victims, Vilnius, Lithuania. -

The Future of Relics from a Military Past

The future of relics from a military past A study to the history, contemporary role and future development of 20th century military heritage at the waterfront of Tallinn, Estonia W. van Vliet 1 2 The future of relics from a military past A study to the history, contemporary role and future development of 20th century military heritage at the waterfront of Tallinn, Estonia STUDENT Wessel van Vliet s2022524 [email protected] SUPERVISOR Prof.dr.ir. T. (Theo) Spek 2ND READER Dr. P.D. (Peter) Groote 3RD READER Dr. T. (Tiina) Peil STUDY Master Landscape History Faculty of Arts University of Groningen DATE March 2016 3 4 Abstract The future of relics from a military past A study to the history, contemporary role and future development of 20th century military heritage at the waterfront of Tallinn, Estonia In comparison to Western Europe, the countries in Central- and Eastern Europe witnessed a complex 20th century from a geopolitical perspective, whereas numerous wars, periods of occupation and political turnovers took place. Consequently, the contemporary landscapes are bearing the military imprint of different political formations and face problems regarding the reuse and domestication of the military remnants. In this thesis, the post-military landscape at the inner-city coast of Tallinn, Estonia, has been studied. The main objective was to get insight in the historical background, contemporary role and future development of military heritage in the Tallinn Waterfront area. The research consists out of two parts. First of all, the historical layering of the Tallinn Waterfront area has been unfolded by elaborating a landscape- biographical approach and making an inventory of military remnants. -

Fall 2018 Newsletter

FALL 2018 NEWSLETTER VOC Rallies for Religious Freedom in Asia In July we participated officially in the first-ever “Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom” hosted by the State Department in Washington, D.C. The gathering—led by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom Sam Brownback, and with a keynote by Vice President Mike Pence—convened leaders from across the human rights community and delegations from over 80 nations for three days of productive talks on how to combat persecution and ensure greater respect for religious liberty. In coordination with the Ministerial, VOC hosted a Rally for Religious Freedom in Asia at the U.S. Capitol in observance of Captive Nations Week, a tradition established in 1959 by President Eisenhower to recognize nations VOC held a Rally for Religious Freedom in Asia on Capitol Hill on July 23 in coordination with the State suffering under communist tyranny. Department’s Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom. Left to Right: Kristina Olney (VOC), Dolkun Isa, Golog Jigme, Paster Nguyen Cong Chinh, Bhuchung Tsering, David Talbot (VOC). Our six speakers were: Rep. Alan in The Hill, Radio Free Asia, and The belief is such an important part of Lowenthal (D-CA) and co-chair of the Washington Examiner. one’s existence that it should not be Congressional Vietnam Caucus; Sen. controlled by the government.” Ted Cruz (R-TX); Pastor Nguyen Cong In his remarks, Pastor Chinh recounted Chinh, former prisoner of conscience how “my family and church have Sen. Ted Cruz spoke -

Trash, Culture, and Urban Regeneration in Tallinn, Estonia

Francisco Martínez ‘THIS PLACE HAS POTENTIAL’: TRASH, CULTURE, AND URBAN REGENERATION IN TALLINN, ESTONIA abstract The article analyses the use of cultural programmes and trash as tools for urban speculation in Tallinn, Estonia, naturalising an urban strategy that entails extensive spatial revaluation and socioeconomic intervention. Through an anthropological perspective focused on concepts of potential and trash, the analysis shows how the central-north shoreline was mobilised discursively as a wasteland and a zone of unrealised potential to justify capitalist development of the area. The way it was framed, both moving towards completion and as a playground for cultural activities and young people, increased the value and accessibility of the area, but also allowed real estate developers to exploit the synergies generated and make profit from the revaluated plots. Tropes of potential and trash appear thus as discursive tools for urban regeneration, co-related with a formal allocation of resources and official permits. As the case study shows, when an area is classed as having ‘potential’, it becomes defined by the fulfilment of that restrictive conceptualisation, which allows the economy to dictate urban planning and also cultural policy. Keywords: politics of potentiality, urban regeneration, European Capital of Culture, waterfront of Tallinn, temporary uses, wasteland 1 INTRODUCTION to connect the place with an image of moving towards completion while emphasising its What does it mean for a place to have potential? negative associations. I start by investigating Potential for what? And cui prodest (to whose the relations occurring there and then develop profit)? This article examines how discourses of an analysis of the recent discussions and public ‘potential’ and ‘trash’ have created the conditions statements on the topic, arguing that discourses for a speculative regeneration of an industrial of trash and unrealised potential were used to area of the Estonian capital. -

INTERVIEW with LAGLE PAREK in August 1987, Shortly Before the 48Th Anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Editor M. Kadast

INTERVIEW WITH LAGLE PAREK In August 1987, shortly before the 48th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, editor M. Kadastik of the newspaper Edasi (Forward) interviewed former political prisoner Lagle Parek. The interview was not published in full. However, the press of the Estonian S.S.R. used excerpts from it, arbitrarily removing them from the original context and presenting them tendentiously. Question: Your term of deprivation of freedom was shorter than the sentence imposed by the court in 1983. For what reasons and on what conditions was the length of your sentence shortened? Answer: My social activism, for which the Supreme Court of the E.S.S.R. imposed a severe sentence - - 6 years in a corrective labor colony with strict regime followed by three years' internal exile - - was carried out in the period that has recently been labeled the "years of stagnation." Even before the XXVII Congress of the C.P.S.U., the domestic and foreign policy of the U.S.S.R. showed the promise of some changes in the direction of democracy. Along with most of my fellow prisoners in the Barashevo harsh-regime women's camp of the Mordovian Autonomous S.S.R., we approached the XXVII Congress with a petition calling for the liquidation of our prison camp, which at that time contained ten prisoners. We also proposed that all the articles pertaining to anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda, and all those pertaining to the spreading of deliberate fabrications defaming Soviet national and social order - - Articles 68 and 194 in the E.S.S.R. -

Patarei Vangla

240 Patarei vangla Meelis Maripuu Patarei vanglakompleks Tallinna lahe kaldal on aastakümnetega kuju- nenud ainulaadseks mälestusmärgiks, paigaks, mida enda ja oma kaas- võitlejate ohverdamiskohana on käsitanud ja käsitavad ka tänapäeval pal- jud inimesed, sõltumata sellest, kas neid vanglasse saatnud võim tegi seda meie praeguste arusaamade kohaselt õiguspäraselt või kuritegelikult. Järgneva artikli keskmes on eelkõige Patarei ajalugu aastatel 1940– 1945, kui see oli Nõukogude ja Saksa okupatsioonirežiimide vaheldudes kõige intensiivsemate repressioonide keskus Eestis. Uuritakse Patarei toi- mimist järjepideva vanglainstitutsioonina eri okupatsioonirežiimide ajal ja Patareis kinni peetud vahialustele esitatud süüdistusi sõltuvalt parajasti võimul olnute vaenlasemääratlusest. Eri ohvrirühmade esiletoomine on oluline Patarei kui mälestuspaiga kujundamisel ja hoidmisel. Patarei vangla enne 1940. aastat 1919. aastal korrastas noor Eesti Vabariik oma asutusi ja selle käigus koondati vanglad kui riigi karistusvõimu toimimiseks vältimatud asutu- sed demokraatlikule riigikorrale omaselt kohtuministeeriumi valitsus- alasse. Seni olid vanglad allunud omavalitsustele. Kohtuministeeriumile (1929–1934 kohtu- ja siseministeerium) allus Patarei vangla kuni Eesti okupeerimiseni 1940. aasta suvel. 1940. aasta augustis, kui okupeeritud Eesti valitsemiskorraldus ühtlustati NSV Liidu omaga, allutati vanglad siseasjade rahvakomissariaadi vanglate valitsusele. 1920. aastatest alates püsis Eesti vanglate võrgustik suuremate muutusteta. Riigis oli 14 vang- lat: -

THE POWER of Mart Laar

THE POWER OF FREEDOM CENTRAL AND E ASTERN E UROPE AFTER 1945 Mart Laar CONTENTS Azymtw .................................................. ............................................. 6 Ahpst|qjilrjsyx ................................................... ........................... 7 Ftwj|twi .................................................. ......................................... 8 Os ymj tymjw xnij tk ymj hzwyfns ................................................... ....13 The old New Europe .................................................. ........................13 Between Two Evils—Central and Eastern Europe during the Second World War ................................................... .22 Back to the shadow: the Communist takeover and the Red Terror . .33 Usual Communism .................................................. ..........................49 East and West Compared ................................................... .59 Tt|fwi Fwjjitrì Tmj Fnlmy flfnsxy Ctrrzsnxy Dtrnsfynts . .69 The Fight Begins: the Start of the Cold War ................................................69 The forgoen war: armed resistance to Communism 1944-1956 . .73 East Germany 1953 .................................................. ..........................83 The Lost Opportunity: 1956 ................................................... .87 Prague, 1968 .................................................. .................................100 Turning the tide: a Polish Pope and Solidarity ............................................107 Winning the Cold -

The Patarei Sea Fort: Perspectives on Heritage, Memory and Identity Politics in Post-Soviet Estonia

international journal for history, culture and modernity 8 (2020) 128-149 brill.com/hcm The Patarei Sea Fort: Perspectives on Heritage, Memory and Identity Politics in Post-Soviet Estonia Onessa Novak Personal Assistant of Prof. R. Braidotti at Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands [email protected] Gertjan Plets Assistant Professor in Cultural Heritage and Archaeology, Department of History and Art History, Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands [email protected] Abstract This paper studies the struggle over the rehabilitation of the Patarei Sea Fort in Tallinn (Estonia), a former prison where during the Soviet period political prisoners were held and corralled before deportation to Siberia. We explore how three groups of stakehold- ers assemble and define the future of the site: The Estonian State; ngo Eesti Muinsus- kaiste Selts (the Estonian Heritage Society); and Europa Nostra. Each of these groups have a competing future for the site in mind. The struggle over the Patarei Sea fort is connected to discussions over heritage politics in those countries that entered the Eu- ropean Union around the early 2000s. In comparison to other memory practices in the region, the Patarei Sea Fort is not instrumentalized by the state to support a national historical narrative othering the Russian Federation. Rather the state’s engagement with the site is restricted and textured by ambitions to gentrify the district it is situated in. Not the state, but an ngo, assisted by a European heritage association, promotes a heritage discourse geared at strengthening the Estonian national narrative. Keywords post-soviet heritage – Estonia – politics of history and memory – gentrification – national narratives © Novak and Plets, 2020 | doi:10.1163/22130624-00801007 This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY-NCDownloaded 4.0 License. -

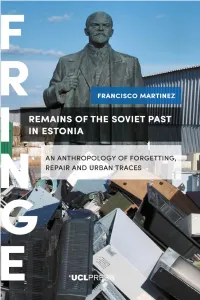

Remains of the Soviet Past in Estonia Ii

Remains of the Soviet Past in Estonia ii FRINGE Series Editors Alena Ledeneva and Peter Zusi, School of Slavonic and East European Studies, UCL The FRINGE series explores the roles that complexity, ambivalence and immeas- urability play in social and cultural phenomena. A cross-disciplinary initiative bringing together researchers from the humanities, social sciences and area stud- ies, the series examines how seemingly opposed notions such as centrality and marginality, clarity and ambiguity, can shift and converge when embedded in everyday practices. Alena Ledeneva is Professor of Politics and Society at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies of UCL. Peter Zusi is Lecturer at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies of UCL. By adopting the tropes of ‘repair’ and ‘waste’, this book innovatively manages to link various material registers from architecture, intergen- erational relations, affect and museums with ways of making the past pres- ent. Through a rigorous yet transdisciplinary method, Martínez brings together different scales and contexts that would often be segregated out. In this respect, the ethnography unfolds a deep and nuanced analysis, providing a useful comparative and insightful account of the processes of repair and waste making in all their material, social and ontological dimensions. Victor Buchli, Professor of Material Culture at UCL This book comprises an endearingly transdisciplinary ethnography of postsocialist material culture and social change in Estonia. Martínez creatively draws on a number of critical and cultural theorists, together with additional research on memory and political studies scholarship and the classics of anthropology. Grappling concurrently with time and space, the book offers a delightfully thick description of the material effects generated by the accelerated post-Soviet transformation in Estonia, inquiring into the generational specificities in experiencing and relating to the postsocialist condition through the conceptual anchors of wasted legacies and repair.