Reference Points, Prospect Theory and Momentum on the PGA Tour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

QUIZ #1 1. If You Score a 3 on a Par 4, What Did You Make? A. Bogey B

QUIZ #1 1. If you score a 3 on a par 4, what did you make? A. Bogey B. Par C. Birdie D. Eagle 2. True or False: After playing a round of golf, you should always shake hands with the people you played with. TRUE FALSE 3. How many holes are on a regulation golf course? A. 10 holes B. 16 holes C. 18 holes D. 22 holes 4. Who plays first: A. The player closest to the hole. B. The player farthest from the hole. 5. Name 3 parts of the golf club: __________________ __________________ __________________ Extra Credit:________________ 6. True or False: Running on the putting green is ok. TRUE FALSE 7. True or False: A putting stroke is made with a lot of hand action, active legs, and very little shoulder motion. TRUE FALSE 8. When you align yourself to the flag to hit a full golf shot, what should be lined up with the flag? A. Your Feet B. Your Golf Club 9. True or False: Stretching before you play is not necessary. TRUE FALSE 10. Where do you place your coin or marker on the green when you need to mark your ball? A. Directly In front of your ball B. Directly Behind your ball C. To the side of the ball D. All of the above 11. Where should you stand while someone else is putting? A. Right behind the hole so you can watch the ball go in the hole. B. Out of the player's line of sight. C. Side by side with the players putting. -

Open Challenges

as seen in In every issue, we share one story across our network that explores topics beyond the limits of the South Bay. These California stories speak to the meaningful impact our state and its residents are making on the global stage. To learn more about Golden State and discover more stories like this, visit goldenstate.is. open challenges THE WORLD’S GREATEST GOLFERS WILL RETURN TO TORREY PINES GOLF COURSE IN JUNE TO COMPETE IN THE U.S. OPEN. AFTER LEADING TWO SEPARATE COURSE RENOVATIONS THERE, ARCHITECT REES JONES DISCUSSES THE FINAL DESIGN TOUCHES TO A CHAMPIONSHIP LAYOUT READY TO TEST THE WORLD’S MOST ELITE GOLFERS. Written by Shaun Tolson COURTESY OF: TORREY PINES GOLF COURSE GOLF PINES TORREY OF: COURTESY When the first tee shot is struck on a second time seven years later. Although the course enjoyed a long-standing history as an Because San Diego owns and manages Torrey Pines, annual venue for a PGA Tour event, the layout lacked the the South Course at Torrey Pines on city residents can play the U.S. Open course for as requisite innate difficulty of a U.S. Open venue. Jones and the morning of June 17—a golf shot little as $63 during the week and $78 on the weekend. his team were charged with the task of changing that. that will signify the start of the 121st Nonresidents must pay significantly more ($202 during Unlike some course design projects that attract numer- the week and $252 on the weekend). But those greens ous architects submitting bids for the work, Torrey Pines U.S. -

West Virginia Open History Compiled by Bob Baker

West Virginia Open History Compiled by Bob Baker 1933: Johnny Javins, the pro at Edgewood Country Club in Charleston, defeated pro I. C. ""Rocky''' Schorr of Bluefield Country Club in an 18-hole playoff at Kanawha Country Club in South Charleston to win the first West Virginia Open. Javins shot a 76 in the playoff while Schorr had an 82. They agreed to split first and second place money but Javins got the trophy donated by George C. Weimer of St. Albans. Javins and Schorr had tied after 72 holes of medal play with 302 scores. Schorr held a five-stroke lead over the field and an 11-stroke edge over Javins after two rounds but faltered on the second 36-hole day. Schorr's troubles started when he took a nine on the par-four third hole, needing five strokes to get out of a trap. Javins began his comeback with a 69 in the third round to pick up all 11 strokes on Schorr. The West Virginia Professional Golfers Association was formed in a meeting a month before the tournament, with Schorr the first president. Leaders by rounds: first, Schorr 72, by one; second, Schorr 147, by five; third, Javins and Schorr, 227s. Johnny Javins, Charleston 80-78-69-75--302 I. C. Schorr, Bluefield 72-75-80-75--302 Rader Jewett, Wheeling 81-73-77-77--308 a-Alex Larmon, Charleston 86-77-73-72--308 A. J. Chapman, Wheeling 81-82-75-74--312 Gordon Murray, Charleston 80-81-72-80--313 Kermit Hutchinson, Charleston 75-85-76-78--314 Joe Fungy, Martinsburg 73-79-80-83--315 B. -

2021 PGA Championship (34Th of 50 Events in the 2020-21 PGA TOUR Season)

2021 PGA Championship (34th of 50 events in the 2020-21 PGA TOUR Season) Kiawah Island, South Carolina May 20-23, 2021 FedExCup Points: 600 (winner) Ocean Course at Kiawah Par/Yards: 36-36—72/7,876 Purse: TBD Third-Round Notes – Saturday, May 22, 2021 Weather: Partly clouDy. High of 79. WinD E 8-13 mph. Third-Round Leaderboard Phil Mickelson 70-69-70—209 (-7) Brooks Koepka 69-71-70—210 (-6) Louis Oosthuizen 71-68-72—211 (-5) Kevin Streelman 70-72-70—212 (-4) Christian Bezuidenhout 71-70-72—213 (-3) Branden Grace 70-71-72—213 (-3) Things to Know • Five-time major champion and 2005 PGA Championship winner Phil Mickelson holds a one-stroke lead and is looking to become the first player to win a men’s major championship after turning 50 years old • Mickelson is the fourth player to hold the 54-hole lead/co-lead in a major at age 50 or older during the modern era (1934-present) • Mickelson is 3-for-5 with the 54-hole lead/co-lead in major championships (21-for-36 in 72-hole PGA TOUR events) • 2018 and 2019 PGA Championship winner Brooks Koepka is one stroke back of Mickelson; last player to win the same major at least three times in a four-year stretch: Tom Watson, The Open Championship (1980, 1982, 1983) • Sunday’s final pairing includes two players that have combined for nine major championship titles (Mickelson/5, Koepka/4) Third-Round Lead Notes 13 Third-round leaders/co-leaders to win the PGA Championship since 2000 Tiger Woods/2000, David Toms/2001, Shaun Micheel/2003, Vijay Singh/2004, Phil Mickelson/2005, Tiger Woods/2006, Woods/2007, -

2021 World Golf Championships-Workday Championship at the Concession (20Th of 50 Events in the PGA TOUR Season)

2021 World Golf Championships-Workday Championship at The Concession (20th of 50 events in the PGA TOUR Season) Bradenton, Florida February 25-28, 2021 Purse: $10,500,000 ($1,820,000) The Concession Golf Club Par/Yards: 36-36—72/7,564 FedExCup Points: 550 (winner) Third-Round Notes – Saturday, February 27, 2021 Weather: Sunny, with a high of 87. Wind WSW at 10-20 mph. Third-Round Leaderboard Collin Morikawa 70-64-67—201 (-15) Billy Horschel 67-67-69—203 (-13) Brooks Koepka 67-66-70—203 (-13) Webb Simpson 66-69-69—204 (-12) Things to Know • Collin Morikawa takes his second 54-hole lead/co-lead on TOUR in search of his first WGC title and fourth career TOUR victory • Brooks Koepka seeks to become the first multiple winner this season and capture second career WGC title • Billy Horschel looks to capture first individual title on TOUR since 2017 AT&T Byron Nelson • Seven-time TOUR winner Webb Simpson in search of his first WGC title in 21st appearance • Defending champion Patrick Reed seeks to win the WGC-Workday Championship at a different course for the third time • Rory McIlroy looks to join Dustin Johnson as the only player with all four World Golf Championships titles Third-Round Lead Notes 11 Third-round leaders/co-leaders at WGC-Workday Championship to win (since 1999) (Most recent: Dustin Johnson/2019) 7 Third-round leaders/co-leaders to win on TOUR in 2020-21 (Most recent: Patrick Reed/Farmers Insurance Open) Collin Morikawa (1st/-15) entering the week Category Collin Morikawa Age 24 (February 6, 1997) FedExCup 81 OWGR 6 Starts at WGC-Workday 1 Wins at WGC-Workday - Top-10s at WGC-Workday - Career PGA TOUR starts 40 Career PGA TOUR wins 3 Career PGA TOUR top-10s 12 PGA TOUR starts in 2020-21 8 PGA TOUR wins in 2020-21 - PGA TOUR top-10s in 2020-21 2 • Marks second 54-hole lead/co-lead on TOUR (2019 3M Open/T2) • Made five consecutive birdies (Nos. -

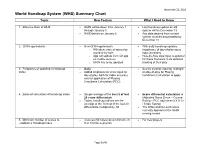

World Handicap System (WHS) Summary Chart Topic New Feature What I Need to Know

November 22, 2019 World Handicap System (WHS) Summary Chart Topic New Feature What I Need to Know • 1. Effective Date of WHS • GHIN will be down from January 1 • Last handicap update on old through January 5 system will be December 15 • WHS debuts on January 6 • Any data desired from current system must be downloaded by December 31 • 2. GHIN app/website • New GHIN app/website • With daily handicap updates, o Will allow entry of scores by importance of day-of-play score round or by hole input increases o App will update from old app • Hole-by-hole data input is optional on mobile devices for those that want to do detailed o GHIN site to be updated tracking of their play • 3. Frequency of updating a Handicap • Daily • Scores must be input by midnight Index • Added emphasis for score input on on day-of-play for Playing day of play, both for index accuracy Conditions Calculation to apply and for application of Playing Conditions Calculation (PCC). • 4. Basis of calculation of Handicap Index • Simple average of the best 8 of last • Score differential calculation is 20 score differentials (Adjusted Gross Score – Course • Today, handicap indices are the Rating – PCC adjustment) X (113 average of the 10 best of the last 20 / Slope Rating) differentials multiplied by .96 • The differential for each score currently appears in the GHIN scoring record • 5. Minimum number of scores to • 3 scores (54 holes) as a minimum, in • For new players establish a Handicap Index 9 or 18 hole segments Page 1 of 6 November 22, 2019 World Handicap System (WHS) Summary Chart Topic New Feature What I Need to Know • 6. -

Assessing Golfer Performance on the PGA TOUR

Vol. 42, No. 2, March–April 2012, pp. 146–165 ISSN 0092-2102 (print) ISSN 1526-551X (online) http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/inte.1120.0626 © 2012 INFORMS Assessing Golfer Performance on the PGA TOUR Mark Broadie Graduate School of Business, Columbia University, New York, New York 10027, [email protected] The game of golf involves many different types of shots, including long tee shots (typically hit with a driver), approach shots to greens, shots from the sand, and putts on the green. Although determining the winner of a golf tournament by counting strokes is easy, assessing which factors contributed most to the victory is not. In this paper, we apply an analysis based on strokes gained, introduced previously, to assess professional golfer performance in different parts of the game [Broadie M (2008) Assessing golfer performance using Golfmetrics. Crews D, Lutz R, eds. Sci. Golf V: Proc. World Sci. Congress Golf (Energy in Motion, Inc., Mesa, AZ), 253–262]. Strokes gained is a simple and intuitive measure of each shot’s contribution to a golfer’s score and was imple- mented by the PGA TOUR to measure putting in May 2011. We apply strokes gained analysis to extensive ShotLink™ data to rank PGA TOUR golfers in various skill categories and to quantify the factors that differen- tiate these golfers. Long-game shots (those starting over 100 yards from the hole) explain about two-thirds of the score variability among PGA TOUR golfers. Tiger Woods is ranked first in total strokes gained, and at or near the top of PGA TOUR golfers in each of the three main categories: long game, short game, and putting. -

Footgolf Game

THIS GAME IS PLAYED, FOR THE MOST PART, WITHOUT THE SUPERVISION Play the ball from where it lies: OF A REFEREE. THE GAME DEPENDS ON THE INTEGRITY OF THE PLAYER 7. It's not allowed to move the ball or TO SHOW CONSIDERATION FOR OTHER PLAYERS AND TO ABIDE BY THE remove jammed objects. RULES. ALL PLAYERS SHOULD CONDUCT THEMSELVES IN A DISCIPLINED MANNER, DEMONSTRATING COURTESY AT ALL TIMES AND Exception: You may mark the spot and lift the ball when it may SPORTSMANSHIP, REGARDLESS OF HOW COMPETITIVE THEY MAY BE. obstruct the other players kick or ball in any way. THIS IS THE SPIRIT OF THE FOOTGOLF GAME. The player farthest from the hole is the first 8. to kick the ball. 1. Wear appropriate clothing. If the ball lands in a water hazard, 9. retrieve or replace it within 2 steps HEAD from the closest land point from TORSE Flat cap or Driver hat. where the ball entered the water, Shirt with collar. receiving one penalty point or you can place the ball at the position of LEGS the previous kick and receive one WOMEN ARE EXPECTED TO Knee-high Argyle WEAR COLLARED SHIRT AS penalty point. WELL socks. TROUSERS Only on the greens may the balls be FEET Golf pants or shorts. 10. picked up to be cleaned or replaced. Indoor or turf soccer shoes. Regardless of the distance from the hole, the hole must NOT ALLOWED: NO SWIMWEAR OR be completed. "Giving" to the opponent is not allowed. SHORT SHORTS. NOT ALLOWED: Soccer uniforms of any kind WOMEN MAY ALSO WEAR or soccer shoes with SHORTS OR SKIRTS. -

What Is the Ryder Cup? He Ryder Cup Is a in Paris, France

chaskatoday PREPARED AND PAID FOR OUR COMMUNITY VALUES BY THE CITY OF CHASKA citizenship | responsibility | respect | generosity | environmentalism | human worth & dignity | integrity | learning September 2016 What is the Ryder Cup? he Ryder Cup is a in Paris, France. The Ryder Cup began with and George Duncan played golf match played Within three days each an Englishman’s new passion against Open Champion Jim Tevery two years since team will have five sessions of for golf. His name was Samuel Barnes and the great Walter 1927 between two, twelve- match-play. One point is given Ryder. Ryder was a seed Hagen. He was so enthralled member teams; one team to the winner of each match; merchant and entrepreneur he said, “We must do this from the United States and a half point is given when a who sold penny seed packets. again.” Ryder donated a small one team from Europe. Each match ends in a draw. The Late in his life he took up gold cup that cost £250 and time the match alternates first team to reach 14 ½ points golfing to improve his health. had a small golf figure at locations between the US and wins the Ryder Cup. If both Ryder had hired Abe Mitchell, the top that is a memorial to Europe. In 2014 the match teams have 14 points at the a great golfer of that era, Abe Mitchell. The Ryder Cup was played at Gleneagles end of the match, the previous to teach him how to play. In trophy measures 17 inches tall, in Perthshire, Scotland. -

Download Rules

TYPES OF COMPETITIONS PLAYED STROKE COMPETITIONS Scores in stroke competitions are achieved by recording the stroke taken on each hole. The scores for all 18 holes are added up at the completion of the round to calculate the Gross score which is recorded in the Gross box. The Nett score is calculated by subtracting a player’s handicap from the player’s Gross score and is recorded in the Nett box. STABLEFORD COMPETITIONS A player’s score in Stableford competitions are converted into points at each hole played in relation to his/her handicap. The Stroke Index column on the score card indicates how many strokes a player receives on a hole. E.G. A player with a handicap of 12 would receive one stroke on each hole with a Stroke Index of 1 to 12 but would not receive a stroke on the other six holes with Stroke Index of 13 to 18. A player with a handicap of 19 would receive one stroke on each hole except when playing the hole with a Stroke Index of 19 where they would receive two strokes. The player’s score for each hole should be placed in the appropriate column (e.g. your score in the Marker 1 column) and the points in the Result column. If a player has played too many shots on a particular hole and cannot score any points on that hole they should pick up their ball to help speed up play. The points are added up at the completion of the round and recorded in the Nett box. -

Putter Design - Kronos Golf By

Putter Design - Kronos Golf by Alex Bartlett Eric Hanaman Joey Gavin Project Advisor: Andrew Davol Instructor’s Comments: Instructor’s Grade: ______________ Date: _________________________ 1 Putter Design - Final Design Review ME430 - Senior Design Project III Project Sponsored By: Phillip Lapuz of Kronos Golf Project Advisor: Andrew Davol - [email protected] Team Members: Eric Hanaman - [email protected] Alex Bartlett - [email protected] Joey Gavin - [email protected] Mechanical Engineering Department California Polytechnic State University San Luis Obispo 2017 2 Statement of Disclaimer Since this project is a result of a class assignment, it has been graded and accepted as fulfillment of the course requirements. Acceptance does not imply technical accuracy or reliability. Any use of information in this report is done at the risk of the user. These risks may include catastrophic failure of the device or infringement of patent or copyright laws. California Polytechnic State University at San Luis Obispo and its staff cannot be held liable for any use or misuse of the project. 3 Table of Contents Table of Contents ................................................................................................................... 4 List of Figures ......................................................................................................................... 5 List of Tables .......................................................................................................................... 6 Chapter 1: Introduction -

120Th U.S. OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP – FACT SHEET

120th U.S. OPEN CHAMPIONSHIP – FACT SHEET Sept. 17-20, 2020, Winged Foot Golf Club (West Course), Mamaroneck, N.Y. mediacenter.usga.org | usopen.com | @usga_pr (media Twitter) | @usopengolf (Twitter and Instagram) | USOPEN (Facebook) | #USOpen iOS and Android mobile app: U.S. Open Golf Championship PAR AND YARDAGE Winged Foot Golf Club’s West Course will be set up at 7,477 yards and will play to a par of 35-35—70. The yardage for each round of the championship will vary due to course setup and conditions. HOLE BY HOLE Hole 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Total Par 4 4 3 4 4 4 3 4 5 35 Yards 451 484 243 467 502 321 162 490 565 3,685 Hole 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Total Par 3 4 5 3 4 4 4 4 4 35 Yards 214 384 633 212 452 426 498 504 469 3,792 ARCHITECTS Winged Foot Golf Club’s West Course was designed by A.W. Tillinghast and opened for play on Sept. 8, 1923. Tillinghast, who also designed Winged Foot’s East Course, competed in two U.S. Opens and eight U.S. Amateurs between 1902 and 1912. Gill Hanse supervised a renovation of the West Course and that work was completed in 2017. He had previously renovated the East Course. ENTRIES The championship is open to any professional golfer and any amateur golfer with a Handicap Index® not exceeding 1.4. Since 2012, the USGA has annually surpassed the 9,000 mark in entries, with a record 10,127 entries accepted for the 2014 U.S.