A Tribute to Mohammad Hidayatullah Bertram F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learn About Presidents of India Through Mnemonics for SSC & Banking Exams

Learn About Presidents of India through Mnemonics for SSC & Banking Exams Presidents of India is one of the most important topics for Polity & Static GK. Questions related to Presidents of India as part of General Awareness section, often appear in exams like SSC CGL, SSC CPO, SSC MTS, SSC CHSL, RPF etc. To aid your preparation for the same, we are providing you a list of Presidents from 1947 to 2019 along with key information about them. Presidents of India & Indian Presidential Elections • The President of India is known as the First Citizen of India. • He is the head of the executive, legislature, and judiciary of India. • A president is elected by the members of an Electoral College on the basis of a single transferable vote system. • According to Article 56, once elected a president holds his/her office for 5 years. Now let's quickly check out the complete list of Presidents of India, according to the year in which took their office. List of Presidents of India & their Tenure 1 | P a g e President Year Dr. Rajendra Prasad 1950- 1962 Dr. Sarvepalli Radha Krishna 1962-1967 Zakir Hussain 1967-1969 VV Giri (Acting) 1969 2 | P a g e Mohammad Hidayatullah(Acting) 1969 VV Giri 1969-1974 Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed 1974-1977 B.D. Jatti (Acting) 1977 Neelam Sanjiva Reddy 1977-1982 Giani Zail Singh 1982-1987 R Venkataraman 1987-1992 Shankar Dayal Sharma 1992-1997 KR Narayanan 1997-2002 APJ Abdul Kalam 2002-2007 Pratibha Patil 2007-2012 Pranab Mukherji 2012-2017 Ram Nath Kovind 2017-Till Date 23 Major Facts about Ram Nath Kovind After you have seen the list of Presidents of India, now let's read some major facts related to Presidents of India as questions are frequently asked about them. -

Issue 15:Constitutional Expectation

Paramount Law Times Newsletter Issue no 015 www.paramountlaw.in 1 (For uptodating law and events) 2014-15 – (second half) Issue no 0015 Dated 01 September, 2014 CONSTITUTIONAL EXPECTATION Present Issue : Dr. S. K. Kapoor Ved Ratan Constitutional Expectation Dr. S. K. Kapoor 01 Ved Ratan Constitution is Supreme Chief Justices of India Subhash Nagpal 1. „Constitution of India is Supreme‟. It is the first value of law. All other values of Indian laws are tested for their virtues on the touchstone of the Constitution of India. WELCOME ANNOUNCEMENT 02 State Judicial Services preparations Constitutional Authorities Guidance facility Finding necessity for guidance for all 2. In India, the „Constitutional authorities‟ are the those preparing for State Judicial creation of the Constitution. This being so the Services Competitions Examinations, Constitution regarding its values, functions and Paramount Law Consultants Ltd. has speaks through authorities created by the decided to help with valuable guidance. Constitution itself. Interested persons are welcome. 3. With it, the Constitutional expectation becomes Legal Audit and Moral Audit Services the core question of interpretation for which the Paramount Law Consultants Ltd., Delhi Constitution puts the responsibility upon the has completed its research and is taking judicial organ of state created by the Constitution. up legal audit and moral audit services for the Corporates. 4. And this responsibility has been discharged by the Subhash Nagpal Constitutional Bench of the Supreme Court in its Chairman judgment dated 27-August-2014 in case Manoj Paramount Law Consultants Ltd., Delhi Narula Vs. Union of India in Writ Petition (Civil) No. 289 Of 2005. -

AQAR Format 2019-20

Yearly Status Report - 2019-2020 Part A Data of the Institution 1. Name of the Institution RASHTRASANT TUKADOJI MAHARAJ NAGPUR UNIVERSITY Name of the head of the Institution Dr. Subhash R. Chaudhari Designation Vice Chancellor Does the Institution function from own campus Yes Phone no/Alternate Phone no. 0712-25245417 Mobile no. 9822576404 Registered Email [email protected] Alternate Email [email protected] Address Rashtrasant Tukadoji Maharaj Nagpur, University Jamnalal Bajaj, Administrative Premisis Ambazari Bypass, Road. City/Town Nagpur State/UT Maharashtra Pincode 440033 2. Institutional Status University State Type of Institution Co-education Location Urban Financial Status state Name of the IQAC co-ordinator/Director Dr. Smita Atul Acharya Phone no/Alternate Phone no. 07122040459 Mobile no. 7720819520 Registered Email [email protected] Alternate Email [email protected] 3. Website Address Web-link of the AQAR: (Previous Academic Year) https://www.nagpuruniversity.ac.in/p df/AQAR_18_19_080720.pdf 4. Whether Academic Calendar prepared during Yes the year if yes,whether it is uploaded in the institutional website: Weblink : https://www.nagpuruniversity.ac.in/v2/ 5. Accrediation Details Cycle Grade CGPA Year of Validity Accrediation Period From Period To 1 Four Star 3.08 2001 12-Feb-2001 11-Feb-2006 2 B 2.61 2009 29-Jan-2009 28-Jan-2014 3 A 3.08 2014 10-Dec-2014 09-Dec-2019 6. Date of Establishment of IQAC 08-Sep-2009 7. Internal Quality Assurance System Quality initiatives by IQAC during the year for promoting quality culture Item /Title of the quality initiative by Date & Duration Number of participants/ beneficiaries IQAC RESEARCH REPORT - 15-May-2020 150 COVID-19 AWARENESS 1 CAMPAIGN MIS TRANING REGARDING 29-Jan-2020 54 IQAMS 2 Two Day National Seminar 29-Jul-2020 91 (NAAC) 2 WORKSHOP ON 'IPR-PATENT 02-Jan-2020 100 PROCEDURE & ITS 2 LEGALITIES' Academic and 03-Feb-2020 46 Administrative Audit 5 NIRF 15-Dec-2019 46 365 View File 8. -

Download Brochure

HIDAYATULLAH NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY LEGAL AND SOCIAL SERVICES COMMITTEE ABOUT THE UNIVERSITY Named after one of the great legal luminaries of India Justice Mohammad Hidayatullah, Hidayatullah National Law University was established in May 2003 by the Government of Chhattisgarh with a view to impart and advance legal education by engaging in teaching and research, and to develop among students a sense of responsibility to serve the society in the field of law by taking to advocacy and reforms in law and justice administration system. HNLU has completed the journey of more than one and half a decade and in such a short span of time, it has carved out a niche in the realm of legal education across India and the legacy is soaring towards newer heights day by day. HNLU is the first National Level Institute established in the new State of Chhattisgarh and the sixth Law University in the country. Hon’ble Chief Justice of High Court of Chhattisgarh, Shri P. R. Ramachandra Menon is the Chancellor of the University. Prof. (Dr.) V. C. Vivekanandan, former MHRD Chair Professor of IP Law at NALSAR University and also former Dean of the Rajiv Gandhi School of Law, IIT Kharagpur and School of Law, Bennett University is the Vice Chancellor of the University. Dr. Deepak Kumar Srivastava is the In Charge Registrar of the University. ABOUT THE LEGAL AND SOCIAL SERVICES COMMITTEE Legal Aid – plays an important role in the legal profession and mandate of having national law schools was to have a testing ground for bold experiments in legal education. -

Dated 9Th October, 2018 Reg. Elevation

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA This file relates to the proposal for appointment of following seven Advocates, as Judges of the Kerala High Court: 1. Shri V.G.Arun, 2. Shri N. Nagaresh, 3. Shri P. Gopal, 4. Shri P.V.Kunhikrishnan, 5. Shri S. Ramesh, 6. Shri Viju Abraham, 7. Shri George Varghese. The above recommendation made by the then Chief Justice of the th Kerala High Court on 7 March, 2018, in consultation with his two senior- most colleagues, has the concurrence of the State Government of Kerala. In order to ascertain suitability of the above-named recommendees for elevation to the High Court, we have consulted our colleagues conversant with the affairs of the Kerala High Court. Copies of letters of opinion of our consultee-colleagues received in this regard are placed below. For purpose of assessing merit and suitability of the above-named recommendees for elevation to the High Court, we have carefully scrutinized the material placed in the file including the observations made by the Department of Justice therein. Apart from this, we invited all the above-named recommendees with a view to have an interaction with them. On the basis of interaction and having regard to all relevant factors, the Collegium is of the considered view that S/Shri (1) V.G.Arun, (2) N. Nagaresh, and (3) P.V.Kunhikrishnan, Advocates (mentioned at Sl. Nos. 1, 2 and 4 above) are suitable for being appointed as Judges of the Kerala High Court. As regards S/Shri S. Ramesh, Viju Abraham, and George Varghese, Advocates (mentioned at Sl. -

Tnpsc Bits National

August-7 TNPSC BITS Usain Bolt was beaten by Justin Gatlin and in100m race final at IAAF World Championships in London. First three places, Gold-Justin Gatlin (U.S.) (9.92seconds) Silver-Christian Coleman (U.S.) (9.94seconds) Bronze-Usain Bolt (Jamaica) (9.95seconds) NATIONAL Venkaiah Naidu is the new Vice President of India Former Union Minister Venkaiah Naidu is elected as the 13th Vice President of India. He secured twice as many votes as Gopalkrishna Gandhi, who was opposition parties general candidate. Venkaiah Naidu is sworn in as new Vice president of the country on August 11, 2017. Out of 771 votes cast, Naidu secured 516 votes in his favour, Gandhi managed to get only 244 votes. Since only Parliamentary members are allowed to vote in this election, there were 790 votes in total. Over 98 percent voting was recorded in the vice-presidential election. The tenure of 12th Vice President Mohammad Hamid Ansari ended on August 10th.He has served as Vice President for two continuous terms (2007–2012 and 2012–2017). In the 2012 Vice Presidential election polls, Ansari had bagged 490 and NDA nominee Jaswant Singh 238 votes. Naidu has also been credited as the vice president, who has been elected with the highest number of votes (516 votes) in the past 25 years. Vice presidents of India who were elected unopposed, S.No Name Tenure 1 SarvepalliRadhakrishnan 1952-1957 1957-1962 2 Mohammad Hidayatullah 1979-1984 3 Shankar Dayal Sharma 1987-1992 Vice Presidents who held the post for two tenures, S.No Name Tenure 1 SarvepalliRadhakrishnan 1952-1957 1957-1962 2 Mohammad Hamid Ansari 2007-2012 2012-2017 Hathkargha Samvardhan Sahayata It is the scheme launched by the Ministry of Textiles for handloom weavers. -

Hiram E. Chodosh ______HIRAM E

Hiram E. Chodosh ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ HIRAM E. CHODOSH PRESIDENT AND PROFESSOR OF THE COLLEGE CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Claremont McKenna College, Claremont, California President and Professor of the College (from July 2013) Chair, Council of Presidents, The Claremont Colleges (2016-2017) University of Utah, S.J. Quinney College of Law, Salt Lake City, Utah (2006-2013) Dean and Hugh B. Brown Presidential Professor of Law Senior Presidential Adviser on Global Strategy Case Western Reserve University School of Law, Cleveland, Ohio (1993-2006) Associate Dean for Academic Affairs Joseph C. Hostetler–Baker & Hostetler Professor of Law Director, Frederick K. Cox International Law Center Indian Law Institute, New Delhi, India, (2003) Fulbright Senior Scholar Cleary, Gottlieb, Steen & Hamilton, New York City (1990-1993) Associate Orion Consultants, Inc., New York City (1985-1987) Management Consultant GLOBAL JUSTICE ADVISORY EXPERIENCE Government of Iraq, Director, Global Justice Project: Iraq (2008-2010) United Nations Development Program (Asia), Adviser (2006-2007) World Bank Group, Adviser (2005-2006) International Monetary Fund, Adviser (1999-2004) U.S. State Department, Rapporteur (1993-2003) Page 1 of 25 Hiram E. Chodosh ___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

Securing the Independence of the Judiciary-The Indian Experience

SECURING THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE JUDICIARY-THE INDIAN EXPERIENCE M. P. Singh* We have provided in the Constitution for a judiciary which will be independent. It is difficult to suggest anything more to make the Supreme Court and the High Courts independent of the influence of the executive. There is an attempt made in the Constitutionto make even the lowerjudiciary independent of any outside or extraneous influence.' There can be no difference of opinion in the House that ourjudiciary must both be independent of the executive and must also be competent in itself And the question is how these two objects could be secured.' I. INTRODUCTION An independent judiciary is necessary for a free society and a constitutional democracy. It ensures the rule of law and realization of human rights and also the prosperity and stability of a society.3 The independence of the judiciary is normally assured through the constitution but it may also be assured through legislation, conventions, and other suitable norms and practices. Following the Constitution of the United States, almost all constitutions lay down at least the foundations, if not the entire edifices, of an * Professor of Law, University of Delhi, India. The author was a Visiting Fellow, Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and Public International Law, Heidelberg, Germany. I am grateful to the University of Delhi for granting me leave and to the Max Planck Institute for giving me the research fellowship and excellent facilities to work. I am also grateful to Dieter Conrad, Jill Cottrell, K. I. Vibute, and Rahamatullah Khan for their comments. -

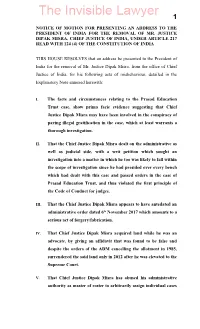

Notice of Motion for Presenting an Address to the President of India for the Removal of Mr

1 NOTICE OF MOTION FOR PRESENTING AN ADDRESS TO THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA FOR THE REMOVAL OF MR. JUSTICE DIPAK MISRA, CHIEF JUSTICE OF INDIA, UNDER ARTICLE 217 READ WITH 124 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA THIS HOUSE RESOLVES that an address be presented to the President of India for the removal of Mr. Justice Dipak Misra, from the office of Chief Justice of India, for his following acts of misbehaviour, detailed in the Explanatory Note annexed herewith: I. The facts and circumstances relating to the Prasad Education Trust case, show prima facie evidence suggesting that Chief Justice Dipak Misra may have been involved in the conspiracy of paying illegal gratification in the case, which at least warrants a thorough investigation. II. That the Chief Justice Dipak Misra dealt on the administrative as well as judicial side, with a writ petition which sought an investigation into a matter in which he too was likely to fall within the scope of investigation since he had presided over every bench which had dealt with this case and passed orders in the case of Prasad Education Trust, and thus violated the first principle of the Code of Conduct for judges. III. That the Chief Justice Dipak Misra appears to have antedated an administrative order dated 6th November 2017 which amounts to a serious act of forgery/fabrication. IV. That Chief Justice Dipak Misra acquired land while he was an advocate, by giving an affidavit that was found to be false and despite the orders of the ADM cancelling the allotment in 1985, surrendered the said land only in 2012 after he was elevated to the Supreme Court. -

List of Reviewers

INDIAN LAW INSTITUTE LAW REVIEW LIST OF REVIEWERS ILI Law Review follows a rigorous blind-peer review of all the articles/case comments/bill comments/book reviews etc. submitted for publications. If you wish to be a reviewer for the upcoming issue of ILI Law Review please convey your details along with areas of interest on which you wish to review articles. Please note that ILI expects a detailed review of the articles in track change mode. We also provide a proforma to the reviewer where specific comments are required to be made regarding the suitability of the article. If any reviewer does not find his/her name or wants a change in the detail mentioned in the list, s/he is also requested to convey on the following email address – [email protected] S.No. Name Designation 1. Aakriti Mathur Advocate, Delhi High Court Research Scholar, IIP, Tokyo 2. Abhinav Kumar Mishra Associate Partner (IP Law), Legal Crescent LLP PhD Scholar, Faculty of Law, Jamia MiliaIslamia, 3. Abhishek Gupta New Delhi 4. Abhilasha Singh LLM, Indian Law Institute, New Delhi Assistant Professor, School of Law, Christ University, 5. Aditi Nidhi Bangalore and Research Scholar, GNLU, Gujarat 6. Aditi Singh Research Scholar, USLLS, GGSIPU, New Delhi 7. Aditya Ranjan PhD Scholar, Faculty of Law, Delhi University Associate Professor, School of Law, Galgotia 8. Ajit Kaushal (Dr.) University, Greater Noida 9. Aman Deep Singh (Dr.) Assistant Professor, RMLNLU, Lucknow Assistant Professor, Faculty of Law, Manav Rachna 10. Amit Kumar University, Faridabad 11. Amit Raj Agarwal Legal Advisor, Forum for Democracy and Academician Regional PF Commissioner and Head of legal division, 12. -

Law Ranking 2021

EDUCATION POST | December 2020 | 39 IIRF-2021 | BEST LAW COLLEGES (GOVT.) LAW COLLEGES (GOVERNMENT) TOP 30 RANK* NAME OF LAW COLLEGE CITY STATE 1 National Law School of India University Bengaluru Karnataka 2 National Law University New Delhi Delhi 3 NALSAR University of Law Hyderabad Telangana 4 The WB National University of Juridical Sciences Kolkata West Bengal 5 Dr. Ambedkar Govt. Law College Chennai Tamil Nadu 6 Faculty of Law University of Delhi Delhi Delhi 7 ILS Law College Pune Maharashtra Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law, Kharagpur West Bengal 8 IIT Kharagpur 9 Faculty of Law, Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh Uttar Pradesh 10 Dr. B.R. Ambedkar College of Law Bengaluru Karnataka 11 Maharashtra National Law University Mumbai Maharashtra 12 Gujarat National Law University Gandhinagar Gujarat * Page 6 EDUCATION POST | December 2020 | 40 IIRF-2021 | BEST LAW COLLEGES (GOVT.) RANK* NAME OF LAW COLLEGE CITY STATE 13 Dr. B R Ambedkar National Law University Sonipat Haryana 14 University School of law and Legal Studies New Delhi Delhi 15 National Law University and Judicial Academy Guwahati Assam 16 National Law University Cuttack Odisha 17 Faculty of Law, Banaras Hindu University Varanasai Uttar Pradesh 18 National Law University Jodhpur Rajasthan 19 Faculty Of Law, Jamia Millia Islamia New Delhi Delhi 20 Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law Patiala Punjab 21 National University of Advanced Legal Studies Kochi Kerala 22 The Tamilnadu Dr Ambedkar Law University Chennai Tamilnadu 23 Government Law College Mumbai Maharashtra 24 University College of Law, Osmania University Hyderabad Telangana 25 karnataka State Law University Hubli Karnataka 26 University of Mumbai Law Academy Mumbai Maharashtra New Campus University of Lucknow, Lucknow Uttar Pradesh 27 Faculty of Law 28 National Law Institute University Bhopal Madhya Pradesh 29 Dr. -

HON'ble MR. JUSTICE Mohammad Hidayatullah

January 28, 2015 Paramount Law Times Issue No - 11 (For up-to-dating law and events) 2015 OUR ELEVENTH CHIEF JUSTICE Happy New Year Paramount Law Consultants Wish you all Happy and prosprous New Year. Let Truth be upheld and Justice to prevail. PARAMOUNT LAW CONSULTANTS WELCOME ANNOUNCEMENT State Judicial Services preparations Guidance facility Finding necessity for guidance for all those preparing for State Judicial Services Competitions Examinations, Paramount HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE Law Consultants Ltd. has decided to help MOHAMMAD HIDAYATULLAH with valuable guidance. Interested persons are welcome. Former Chief Justice of India Legal Audit and Moral Audit Services 25-02-1968 till 16-12-1970 Paramount Law Consultants Ltd., Delhi has PROFILE as on Supreme court website completed its research and is taking up legal (http://supremecourtofindia.nic.in/judges/r audit and moral audit services for the cji.htm) Corporates. Subhash Nagpal, o The Hon'ble Mr. Mohammad Chairman Hidayatullah, B.A. (Nagpur) : M.A. Paramount Law Consultants Ltd., Delhi (Cantab); Barrister-at-Law, O.B.E. (1946) : Judge, Supreme Court from Dec. 1, 1958.b. Dec. 17,1905; Educ. : Govt. High School, Raipur (1922) ; Phillip's Scholar, Morris College, For previous issues and more information go to www.paramountlaw.in Page - 1 January 28, 2015 Paramount Law Times Issue No - 11 Nagpur (1926) ; B.A. 2nd order of 2 Title-Ishwardas Vs. Maharashtra merit Malak Gold Medalist, Trinity Revenue Tribunal & Ors.-Coram- College, Cambridge (1927-30), English Hidayatullah, M. (Cj), Bachawat, R.S., and Law Tripos, Lincoln's Inn, Vaidyialingam, C.A., Hegde, K.S., Barrister-at-Law (1930), President, Grover, A.N.