Keeping the Spirit of the Common Law Alive*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dated 9Th October, 2018 Reg. Elevation

SUPREME COURT OF INDIA This file relates to the proposal for appointment of following seven Advocates, as Judges of the Kerala High Court: 1. Shri V.G.Arun, 2. Shri N. Nagaresh, 3. Shri P. Gopal, 4. Shri P.V.Kunhikrishnan, 5. Shri S. Ramesh, 6. Shri Viju Abraham, 7. Shri George Varghese. The above recommendation made by the then Chief Justice of the th Kerala High Court on 7 March, 2018, in consultation with his two senior- most colleagues, has the concurrence of the State Government of Kerala. In order to ascertain suitability of the above-named recommendees for elevation to the High Court, we have consulted our colleagues conversant with the affairs of the Kerala High Court. Copies of letters of opinion of our consultee-colleagues received in this regard are placed below. For purpose of assessing merit and suitability of the above-named recommendees for elevation to the High Court, we have carefully scrutinized the material placed in the file including the observations made by the Department of Justice therein. Apart from this, we invited all the above-named recommendees with a view to have an interaction with them. On the basis of interaction and having regard to all relevant factors, the Collegium is of the considered view that S/Shri (1) V.G.Arun, (2) N. Nagaresh, and (3) P.V.Kunhikrishnan, Advocates (mentioned at Sl. Nos. 1, 2 and 4 above) are suitable for being appointed as Judges of the Kerala High Court. As regards S/Shri S. Ramesh, Viju Abraham, and George Varghese, Advocates (mentioned at Sl. -

Securing the Independence of the Judiciary-The Indian Experience

SECURING THE INDEPENDENCE OF THE JUDICIARY-THE INDIAN EXPERIENCE M. P. Singh* We have provided in the Constitution for a judiciary which will be independent. It is difficult to suggest anything more to make the Supreme Court and the High Courts independent of the influence of the executive. There is an attempt made in the Constitutionto make even the lowerjudiciary independent of any outside or extraneous influence.' There can be no difference of opinion in the House that ourjudiciary must both be independent of the executive and must also be competent in itself And the question is how these two objects could be secured.' I. INTRODUCTION An independent judiciary is necessary for a free society and a constitutional democracy. It ensures the rule of law and realization of human rights and also the prosperity and stability of a society.3 The independence of the judiciary is normally assured through the constitution but it may also be assured through legislation, conventions, and other suitable norms and practices. Following the Constitution of the United States, almost all constitutions lay down at least the foundations, if not the entire edifices, of an * Professor of Law, University of Delhi, India. The author was a Visiting Fellow, Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and Public International Law, Heidelberg, Germany. I am grateful to the University of Delhi for granting me leave and to the Max Planck Institute for giving me the research fellowship and excellent facilities to work. I am also grateful to Dieter Conrad, Jill Cottrell, K. I. Vibute, and Rahamatullah Khan for their comments. -

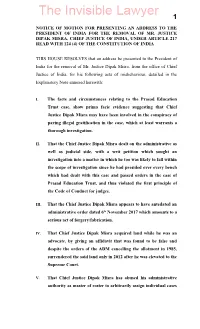

Notice of Motion for Presenting an Address to the President of India for the Removal of Mr

1 NOTICE OF MOTION FOR PRESENTING AN ADDRESS TO THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA FOR THE REMOVAL OF MR. JUSTICE DIPAK MISRA, CHIEF JUSTICE OF INDIA, UNDER ARTICLE 217 READ WITH 124 (4) OF THE CONSTITUTION OF INDIA THIS HOUSE RESOLVES that an address be presented to the President of India for the removal of Mr. Justice Dipak Misra, from the office of Chief Justice of India, for his following acts of misbehaviour, detailed in the Explanatory Note annexed herewith: I. The facts and circumstances relating to the Prasad Education Trust case, show prima facie evidence suggesting that Chief Justice Dipak Misra may have been involved in the conspiracy of paying illegal gratification in the case, which at least warrants a thorough investigation. II. That the Chief Justice Dipak Misra dealt on the administrative as well as judicial side, with a writ petition which sought an investigation into a matter in which he too was likely to fall within the scope of investigation since he had presided over every bench which had dealt with this case and passed orders in the case of Prasad Education Trust, and thus violated the first principle of the Code of Conduct for judges. III. That the Chief Justice Dipak Misra appears to have antedated an administrative order dated 6th November 2017 which amounts to a serious act of forgery/fabrication. IV. That Chief Justice Dipak Misra acquired land while he was an advocate, by giving an affidavit that was found to be false and despite the orders of the ADM cancelling the allotment in 1985, surrendered the said land only in 2012 after he was elevated to the Supreme Court. -

Justice Sabharwal's Defence Becomes Murkier

JUSTICE SABHARWAL’S DEFENCE BECOMES MURKIER: STIFLING PUBLIC EXPOSURE BY USING CONTEMPT POWERS Press Release: New Delhi 19th September 2007 Justice Sabharwal finally broke his silence in a signed piece in the Times of India. His defence proceeds by ignoring and sidestepping the inconvenient and emphasizing the irrelevant if it can evoke sympathy. To examine the adequacy of his defence, we need to see his defence against the gravamen of each charge against him. Charge No. 1. That his son’s companies had shifted their registered offices to his official residence. Justice Sabharwal’s response: That as soon as he came to know he ordered his son’s to shift it back. Our Rejoinder: This is False. In April 2007, in a recorded interview with the Midday reporter M.K. Tayal he feigned total ignorance of the shifting of the offices to his official residence. In fact, the registered offices were shifted back from his official residence to his Punjabi Bagh residence exactly on the day that the BPTP mall developers became his sons partners, making it very risky to continue at his official residence. Copies of the document showing the date of induction of Kabul Chawla, the promoter and owner of BPTP in Pawan Impex Pvt. Ltd., one of the companies of Jutstice Sabharwal’s sons, and Form no. 18 showing the shifting of the registered office from the official residence of Justice Sabharwal to his family residence on 23rd October 2004. Charge No. 2: That he called for and dealt with the sealing of commercial property case in March 2005, though it was not assigned to him. -

Constitutional Ideals and Justice in Plural Societies

L10-2016 Justice MN Venkatachaliah Born on 25th October 1929, he entered the general practice of the law in MN Venkatachaliah the year 1951 at Bangalore after obtaining University degrees in Science and law. Justice Venkatachaliah was appointed Judge of the high court of Karnataka in the year 1975 and later as Judge of the Supreme Court of India in the year 1987. He was appointed Chief Justice of India in February 1993 and held that office till his retirement in October 1994. Justice Venkatachaliah was appointed Chairman, National Human Rights Commission in 1996 and held that office till October 1999. He was nominated Chairman of the National commission to Review the Working of the Constitution in March 2000 and the National Commission gave its CONSTITUTIONAL IDEALS AND Report to the Government of India in March 2002. He was conferred “Padma Vibhushan” on 26th January 2004 by the Government of India. JUSTICE IN PLURAL SOCIETIES Justice Venkatachaliah has been associated with a number of social, cultural and service organizations. He is the Founder President of the Sarvodya International Trust. He is the Founder Patron of the “Society for Religious Harmony and Universal Peace “ New Delhi. He was Tagore Law NIAS FOUNDATION DAY LECTURE 2016 Professor of the Calcutta University. He was the chairman of the committee of the Indian Council for Medical Research to draw-up “Ethical Guidelines for Bio-Genetic research Involving Human Subjects”. Justice Venkatachaliah is the President of the Public Affairs Centre and President of the Indian Institute of World Culture. He was formerly Chancellor of the Central University of Hyderabad. -

The Hon'ble Mr Justice Y K Sabharwal

n 052 im 002 Delhi’s Moot Court Hall named after alumnus Chief Justice of India 14.01.2016 The Hon’ble Mr Justice Y K Sabharwal Mr Justice Y K Sabharwal BA Hons 1961 Hindu LLB 1964 36th Chief Justice of India 1999 – 2000 Former Judge High Court of Delhi Chief Justice High Court of Bombay Passed away 03.07.2015 Jaitley inaugurates Y K Sabharwal Moot Court hall at National Law University Delhi NEW DELHI: Union finance minister Arun Jaitley on Thursday recalled late former Chief Justice of India YK Sabharwal as one of the rare judges who was not only fair but also fearless. He had the “ability to strike” when it was required, the Minister said. Speaking at the inauguration of a moot court hall in Delhi’s National Law University (NLU) — dedicated to the former CJI , Jaitley said Justice Sabharwal was a tough judge but never sat on the bench with fixated views. “He had no likes or dislikes and had no friends in court. But his personality outside was totally different,” Jaitley reminisced, recalling his association with the former CJI who made tremendous contribution to the field of Law through his judgements. Some of the important verdicts delivered by him included declaring President’s Rule in Bihar unconstitutional and opening to judicial review the laws placed in the Ninth Schedule. A Moot Court Hall in his name in a premier law school was a fit dedication to the former CJI, Jaitley said. The Minister added : “A specialised Moot Court hall is a rare speciality and for a law school to have one is commendable.” Justice Dalveer Bhandari, Judge of International Court of Justice, spoke of how moot courts had become an integral part of legal education. -

Commendation by Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah

M. N. VENKATACHALIAH A COMMENDATION OF IIAM COMMUNITY MEDIATION SERVICE VISUALIZED BY THE INDIAN INSTITUTE OF ARBITRATION & MEDIATION. The Indian Institute of Arbitration & Mediation (IIAM), a registered society, has innovated an extremely effective idea of a decentralized, socially oriented and inexpensive Dispute Resolution Mechanism to serve the needs of the common people obviating their recourse to more expensive, embittering and protracted litigations in the courts of law. The formal dispute resolution mechanisms are wholly inappropriate to the aspirations and needs of the common people for speedy justice. I had the privilege of being on the Advisory Board of IIAM along with Mr. Justice J.S. Verma, Former Chief Justice of India, Mr. Justice K.S. Paripoornan, Former Judge, Supreme Court of India, Mr. Prabhat Kumar, Former Cabinet Secretary & Former Governor of Jharkhand, Dr. Madhav Mehra, President of World Council for Corporate Governance, UK, Dr. Abid Hussain, Former Ambassador to the US, Mr. Sudarshan Agarwal, Former Governor of Sikkim, Dr. G. Mohan Gopal, Director of the National Judicial Academy and Mr. Michael McIlwrath, Chairman, International Mediation Institute, The Hague. The Hon’ble Chief Justice of India inaugurated the “IIAM Community Mediation Service” on the 17th of January 2009 at New Delhi. Every participant extolled the great potential of this innovative scheme to bring justice to the doors of the common man under a scheme which provides for voluntary participation with the assistance of experienced lawyers, retired judges, former civil servants and other public spirited people who will act as mediators to bring about a just and mutually acceptable solution to potentially litigative situations. -

Chief Justice of India

CHIEF JUSTICE OF INDIA CHIEF JUSTICE OF INDIA The Chief Justice of India (CJI) is the head of the judiciary of India and the Supreme Court of India. The CJI also heads their administrative functions. In accordance with Article 145 of the Constitution of India and the Supreme Court Rules of Procedure of 1966, the Chief Justice allocates all work to the other judges who are bound to refer the matter back to him or her (for re-allocation) in any case where they require it to be looked into by a larger bench of more judges. The present CJI is Justice Dipak Misra and is the 45th CJI since January 1950, the year the Constitution came into effect and the Supreme Court came into being. He succeeded Justice Jagdish Singh Khehar on 28 August 2017 and will remain in office till 2 October 2018, the day he retires on turning 65 years in age. S.No Name Period 1 H. J. Kania 1950-1951 2 M. Patanjali Sastri 1951-1954 3 Mehr Chand Mahajan 1954 4 Bijan Kumar Mukherjea 1954-1956 5 Sudhi Ranjan Das 1956-1959 6 Bhuvaneshwar Prasad Sinha 1959-1964 7 P. B. Gajendragadkar 1964-1966 8 Amal Kumar Sarkar 1966 9 Koka Subba Rao 1966-1967 10 Kailas Nath Wanchoo 1967-1968 11 Mohammad Hidayatullah[10] 1968-1970 12 Jayantilal Chhotalal Shah 1970-1971 13 Sarv Mittra Sikri 1971-1973 14 Ajit Nath Ray 1973-1977 15 Mirza Hameedullah Beg 1977-1978 16 Yeshwant Vishnu Chandrachud 1978-1985 17 Prafullachandra Natwarlal Bhagwati 1985-1986 18 Raghunandan Swarup Pathak 1986-1989 19 Engalaguppe Seetharamiah Venkataramiah 1989 20 Sabyasachi Mukharji 1989-1990 21 Ranganath Misra 1990-1991 22 Kamal Narain Singh 1991 23 Madhukar Hiralal Kania 1991-1992 24 Lalit Mohan Sharma 1992-1993 25 Manepalli Narayana Rao Venkatachaliah 1993-1994 26 Aziz Mushabber Ahmadi 1994-1997 27 Jagdish Sharan Verma 1997-1998 Page 1 CHIEF JUSTICE OF INDIA 28 Madan Mohan Punchhi 1998 29 Adarsh Sein Anand 1998-2001 30 Sam Piroj Bharucha 2001-2002 31 Bhupinder Nath Kirpal 2002 32 Gopal Ballav Pattanaik 2002 33 V. -

Clcns at TOP GOVERNANCE

SOME OF OUR GLITTERING STARS… CLCns AT TOP GOVERNANCE Late. Shri Arun Jaitley Former Minister of Finance, Minister of Corporate Affairs and Minister of Information and Broadcasting in the Union Cabinet of India Batch (1974 - 1977) Mr. Kiren Rijiju Minister of State of the Ministry of Youth Affairs and Sports and Ministry of State in the Ministry of Minority Affairs Former Minister of State of Home Affairs on the Union Cabinet of India Batch (1990 - 1993) 1 Mr. Kapil Sibal Former Minister of Law and Justice, Minister of Communications and Information Technology of the Union Cabinet of India Batch (1968 - 1970) Mr. Bhupinder Singh Hooda Mr. Jarbom Gamlin Former Chief Minister of Haryana Former Chief Minister of Arunachal Pradesh Batch (1968 - 1971) Batch (1981 – 1984) 2 CLCns AT THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Hon'ble Mr. Justice M.M. Punchhi Hon'ble Mr. Justice Y.K. Sabharwal Former Chief Justice of India Former Chief Justice of India Batch (1952 - 55) Batch (1961 - 1964) Hon'ble Mr. Justice Ranjan Gogoi Former Chief Justice of India Batch (1975- 1978) 3 Hon'ble Mr. Justice Vikramajit Sen Hon'ble Mr. Justice Madan B. Lokur Former Supreme Court Judge Former Supreme Court Judge Batch (1974 - 1977) Batch (1974 - 1977) Hon'ble Mr. Justice Arjan Kumar Sikri Former Supreme Court Judge Batch (1971 - 1974) 4 SITTING JUDGES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF INDIA Hon'ble Mr. Justice Rohinton F. Nariman Hon’ble Dr. Justice D. Y. Chandrachud Batch (1971 - 1974) Batch (1979 – 1982) Hon’ble Mr. Justice Navin Sinha Hon’ble Mr. Justice Deepak Gupta Batch (1976 – 1979) Batch (1975 – 1978) 5 Hon'ble Mr. -

A Judge As a Philosopher

ISSN (Online) - 2349-8846 A Judge as a Philosopher A Tribute to Justice P N Bhagwati BHARAT H DESAI Vol. 52, Issue No. 27, 08 Jul, 2017 Bharat Desai ([email protected]) is professor of International Law, Jawaharlal Nehru Chair & Chairman of the Centre for International Legal Studies, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi as well as the chairman of the Centre for Advanced Study on Courts and Tribunals, Amritsar. The sheer audacity of Justice P N Bhagwati’s vision, philosophical rationale and futuristic imprint of judicial activism appear to be unparalleled. It provides a beacon of hope to us that much desired changes in the Indian legal system are possible. This can happen if conscientious judges with wider horizons can marshal ideas that are duly guided by taking the Constitution as an organic beacon of hope for betterment of the society at large. In the legal annals of independent India, very few judges have left an indelible imprint on justice delivery system and legal mechanisms for societal betterment. One such iconic judge left, after a lifespan of 95 years, for his heavenly abode on 15 June 2017. In fact, Prafullachandra Natwarlal Bhagwati, who was born on 21 December 1921, was a restless legal crusader, who turned his tenure as a judge of the Supreme Court into a unique opportunity to give effect to some of the embedded aspirations of the founding fathers of the Indian Constitution. His illustrious father, N H Bhagwati, served as a Supreme Court judge (1952–59) as well as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Bombay. -

A Tribute to Mohammad Hidayatullah Bertram F

Cornell International Law Journal Volume 16 Article 9 Issue 1 Winter 1983 A Tribute to Mohammad Hidayatullah Bertram F. Willcox Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Willcox, Bertram F. (1983) "A Tribute to Mohammad Hidayatullah," Cornell International Law Journal: Vol. 16: Iss. 1, Article 9. Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol16/iss1/9 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell International Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A TRIBUTE TO MOHAMMAD HIDAYATULLAH My Own Boswell: Memoirs of M. Hidayatullah. MOHAMMAD HIDAYATULLAH. AB/9 Safdarjang Enclave, New Delhi, 110016, India: Gulab Vazirani for Arnold-Heinemann Publishers (India) Pvt. Limited, 1980. Pp. viii, 304 (including Appendices and Index). 85.00 Rupees (cloth). Bertram F Willcox* Judge Mohammad Hidayatullah lectured at the Cornell Law School in 1975. I believe it was during that visit that he noticed, in our library, and liked, Oliver Wendell Holmes's subtitle to the Autocrat of the Breakfast Table: "Every Man His Own Boswell." He adapted it, with a bow to Dr. Holmes, as the title for what was to become his autobiography. For anyone wanting an introduction to the legal world of India-its atmosphere and its ways-or wanting a vividly readable and entertaining account of the life of a great judge and quiet statesman, there could be no more pleasant recommendation than reading these Memoirs. -

The Constitution (Seventy-Fourth) 32 Permanent Legal Services Clinic, Amendment Act, 1992; Protection and Room No

NYAYA KIRAN VOLUME - II ISSUE - II APRIL - JUNE, 2008 DELHI LEGAL INDEX SERVICES AUTHORITY Page No. Patron – in – Chief Message By Smt. Renuka Chowdhury Hon’ble Mr. Justice A. P. Shah Hon’ble Minister of Women & Child Development Chief Justice, High Court of Delhi Message By Smt. Sheila Dikshit Executive Chairman Hon’ble Mr. Justice T. S. Thakur Hon’ble Chief Minister of Delhi Judge, High Court of Delhi Message By Shri Yudhbir Singh Dadwal Chairman, Delhi High Court Legal Commissioner of Police, Delhi Services Committee Hon’ble Mr. Justice Manmohan Sarin ARTICLE SECTION Judge, High Court of Delhi 1. Constitutional Underpinnings of a 1 Member Secretary Concordial Society Ms. Sangita Dhingra Sehgal - Hon’ble Mr. Justice M.N. Venkatachaliah Addl. District & Sessions Judge Former Chief Justice of India Address : Delhi Legal Services Authority, 2. Mediation : As a Technique for Alternative 19 Central Office, Pre-fab Building, Dispute Resolution System Patiala House Courts, - Ms. Kuljit Kaur New Delhi - 110 001. Head, Department of Law Tel. No. 23384638 Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar Fax No. 23387267, 23383014 3. The Constitution (Seventy-Fourth) 32 Permanent Legal Services Clinic, Amendment Act, 1992; Protection and Room No. 54 to 57, Promotion of Democracy (Local Self- Shaheed Bhagat Singh Place, Government), Rule of Law & Human Rights Gole Market, New Delhi. - Dr. J.S. Singh, Sr. Lecturer Tel. No. 23341111 Faculty of Law, University of Allahabad Fax No. 23342222 JUDGMENT SECTION Toll Free No. 12525 1. Case of Sampanis and Others v. Greece 63 Website : www.dlsa.nic.in (Decided on 05.06.08 by the European E-mail : [email protected] Court of Human Rights) Editorial Committee - Ms.