US-India Relations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MA Political Science Programme

Department of Political Science, University of Delhi UNIVERSITY OF DELHI MASTER OF ARTS in POLITICAL SCIENCE (M.A. in Political Science) (Effective from Academic Year 2019-20) PROGRAMME BROCHURE Revised Syllabus as approved by Academic Council on XXXX, 2019 and Executive Council on YYYY, 2019 Department of Political Science, University of Delhi 1 | Page Table of Contents I. About the Department ................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 About the Programme: ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 About the Process of Course Development Involving Diverse Stakeholders .......................... 4 II. Introduction to CBCS (Choice Based Credit System) .............................................................. 5 III. M.A. Political Science Programme Details: ............................................................................ 6 IV. Semester wise Details of M.A.in Political Science Course....................................................... 9 4.1 Semester wise Details ................................................................................................................ 9 4.2 List of Elective Course (wherever applicable to be mentioned area wise) ............................ 10 4.3 Eligibility for Admission: ....................................................................................................... 13 4.4 Reservations/ Concessions: .................................................................................................... -

International Conference TOWARDS a WORLD FREE of NUCLEAR

Programme As on May 28, 2008 International Conference on TOWARDS A WORLD FREE OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS June 9-10, 2008 Venue: Hotel Maurya ITC, New Delhi (Kamal Mahal) June 9, 2008 (Monday) 0830 Registration 0930-1100 Inaugural Session Welcome Remarks: Air Cmde Jasjit Singh AVSM VrC VM (retd) Director, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, New Delhi Keynote Address: Mr Sergio de Queiroz Duarte High Representative for Disarmament Affairs, United Nations Inaugural Address: Dr Manmohan Singh Prime Minister of India 1100-1130 Tea 1130-1330 Session I: Nuclear Weapons in the Contemporary World Chairman: Mr Lalit Mansingh Former Foreign Secretary st Relevance of Nuclear Deterrence in 21 Century - Dr Jonathan Granoff President, Global Security Initiative, USA Nuclear Weapons and International Terrorism - Dr Rajesh Rajagopalan 7 Professor, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Responsibilities of US and Russia in - Senator Douglas Roche Leading the Way to Nuclear Disarmament Former Chairman UN Disarmament Committee 1330-1430 Lunch 1430-1715 Session II: The Non Proliferation Challenge Chairman: Mr Richard Butler Chairman, Canberra Commission Need for a new Global Consensus on - Dr Sverre Lodgaard, Former Director, Norwegian Non-proliferation Institute of International Relations, Oslo Re-establishing the link between - Mr Rakesh Sood Non Proliferation and Nuclear Disarmament Ambassador of India to Nepal Non Proliferation in the Age of - Dr George Perkovich Civil Nuclear Renaissance Vice President, Global Security -

2009-2010, Eight Regular Meetings, Two Special Meetings of the Executive Council Were Held

GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009 -10 )0(V ANNUAL REPORT June 2009— May 2010 GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA 403 206 1 GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 GOA UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR H. E. Dr. S. S. Sidhu VICE-CHANCELLOR Prof. Dileep N. Deobagkar REGISTRAR Dr. M. M. Sangodkar GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009 -10 CONTENTS Pg. No. Pg. No. PREFACE 4 PART 3: ACHIEVEMENTS OF UNIVERSITY INTRODUCTION 5 FACULTY PART 1: UNIVERSITY AUTHORITIES AND A: Seminars Organised 58 BODIES B: Papers Presented 61 1,1 Members of Executive Council 6 C: ' Research Publications 72 1.2 Members of University Court 6 D: Articles in Books 78 1.3 Members of Academic Council 8 E: Book Reviews 80 1.4 Members of Planning Board 9 F: Books/Monographs Published 80 G. Sponsored Consultancy 81 1.5 Members of Finance Committee 9 Ph.D. Awardees 82 1.6 Deans of Faculties 10 List of the Rankers (PG) 84 1.7 Officers of the University 10 PART 4: GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 1.8 Other Bodies/Associations and their 11 Composition General Information 85 Computerisation of University Functions 85 Part 2: UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS/ CENTRES / PROGRAMMES Conduct of Examinations 85 2.1 Faculty of Languages & Literature 13 Library 85 2.2 Faculty of Social Sciences 24 Sports 87 2.3 Faculty of Natural Sciences 31 Directorate of Students' Welfare & 88 Cultural Affairs 2.4 Faculty of Life Sciences & Environment 39 U.G.C. Academic Staff College 88 2.5 Faculty of Management Studies 51 Health Centre 89 2.6 Faculty of Commerce 52 College Development Council 89 2.7 Innovative Programmes 55 (i) Research -

'State Visit' of Shri KR Narayanan, President of the Republic of India To

1 ‘State Visit’ of Shri KR Narayanan, President of the Republic of India to Peru and Brazil from 26 Apr to 10 May 1998 COMPOSITION OF DELEGATION (I) President and Family 1. The President 2. The First Lady 3. 2 x Daughter of the President 4. Granddaughter of the President (II) President’s Secretariat Delegation 1. Shri Gopalkrishna Gandhi Secretary to the President 2. Shri SK Sheriff Joint Secretary to the President 3. Maj Gen Bhopinder Singh Military Secretary to the President 4. Shri TP Seetharam Press Secretary to the President 5. Dr NK Khadiya Physician, President’s Estate Clinic No. of auxiliary staff : 15 (III) Parliamentary Delegation 1. Shri Ananth Kumar Minister of Civil Aviation 2. Shri Bangaru Laxman Member of Parliament (RS) 3. Shri Murli Deora Member of Parliament (LS) No. of supporting staff : 01 2 (IV) Ministry of External Affairs Delegation 1. Shri K Raghunath Foreign Secretary, MEA (for New York only) 2. Shri Lalit Mansingh Secretary (West), MEA 3. Shri Alok Prasad Joint Secretary (AMS), MEA (For New York only) 4. Shri SM Gavai Chief of Protocol, MEA 5. Smt Homai Saha Joint Secretary (LAC), MEA No. of supporting staff : 04 (V) Security Staff Total : 19 (VI) Media Delegation 1. Ms Rizwana Akhtar Correspondent, Doordarshan 2. Shri Sanjay Bhatnagar Correspondent, Univarta 3. Shri Ramesh Chand Cameraman, ANI 4. Dr John Cherian World Affairs Correspondent, Frontline 5. Shri Subhasish Choudhary Chief Recordist, Films Division 6. Ms Seema Goswami Editor, Weekend Magazine, Anand Bazar Patrika 7. Shri Mahesh Kamble Chief Cameraman, Films Division 8. Shri KL Katyal Programme Executive, All India Radio 3 9. -

![Purbasa Conference[Initial].P65](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9942/purbasa-conference-initial-p65-1839942.webp)

Purbasa Conference[Initial].P65

PURBASA: EAST MEETS EAST Synergising the North-East and Eastern India with the Indo-Pacific PURBASA: EAST MEETS EAST Synergising the North-East and Eastern India with the Indo-Pacific Editors Lalit Mansingh Anup K. Mudgal Udai Bhanu Singh PENTAGON PRESS LLPLLP PURBASA: EAST MEETS EAST Synergising the North-East and Eastern India with the Indo-Pacific Editors: Lalit Mansingh, Anup K. Mudgal, Udai Bhanu Singh First Published in 2019 Copyright © Kalinga International Foundation (KIF) ISBN 978-93-86618-64-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining written permission of the copyright owner. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Kalinga International Foundation (KIF), or the Government of India. Published by PENTAGON PRESS LLP 206, Peacock Lane, Shahpur Jat New Delhi-110049 Phones: 011-64706243, 26491568 Telefax: 011-26490600 email: [email protected] website: www.pentagonpress.in Printed at Avantika Printers Private Limited. Contents Preface ix Kalinga International Foundation xi Introduction xiii 1. Welcome Address 1 Lalit Mansingh 2. Inaugural Programme: Summary Report on the Proceedings 5 3. Vote of Thanks at the Kalinga International Foundation: Inaugural Session 9 Shreerupa Mitra ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION 4. India’s Economic Cooperation with East and Southeast Asia 15 V.S. Seshadri 5. Remarks by Ambassador of Vietnam 20 Ton Sinh Thanh 6. Economic Engagement and Connectivity between India’s North East and the Indo-Pacific 23 Anil Wadhwa 7. -

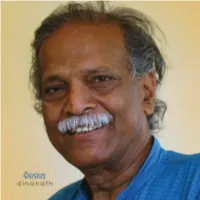

Dr Pathy Book.Pdf

dinanath Published by Third Eye Communications A unit of Ketaki Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. N-4/252, IRC Village, Bhubaneswar Odisha. India 751015 E [email protected] With Support from IPCA ILa Panda Centre for Arts Bhubaneswar Dr. Dinanath Pathy left this material and world doing what he loved most; working for the cause of art and for Print-Tech Offset Pvt. Ltd. what he believed to be right. He left behind a vast expanse of memories and Bhubaneswar experiences which can never be filled in. In this publication we have earnestly tried Concept, Layout and Design to create the memories of the legendary Jyotiranjan Swain painter, writer and art philosopher Satyabhusan Hota through a collection of pictures. There are many more images and memories Photographs which could not be included due to limitations of time and immediate Ramahari Jena, A. Prathap, PC Dhir, availability of materials. We are looking Jyotiranjan Swain, Subrat Das, Sangram forward to touching other aspects of his Jena, Soubhagya Pathy, Abtin Javid, life in our future publications. IPCA, Angarag and Sutra Foundation Dr. Dinanath Pathy 1942-2016 Painter, Writer and Art Historian A distinguished practicing painter and pioneer of the Modern and Contemporary Art Movement of Odisha, Dr. Dinanath Pathy was brought up in a family of artists and poets in the traditional town of Digapahandi, Ganjam in Odisha. In education and training, he combined both traditional Guru-Sisya Parampara as well as the modern university system. He studied at Khallikote, Bhubaneswar, Santiniketan and Zurich. He wrote two dissertations: History of Orissan Painting, and Art and Regional Traditions. -

Up-Dated Ay. Practitioners Voter List-2016.Xlsx

Up‐dated Voter List of Registered Practitioners under Odisha State Council of Ayurvedic Medicine, Bhubaneswar Regd. S.L Name of Regd. No./ Permanent Address Present Address No. Practitioners Year 1 At-Brahman Sahi, Old Town, Po- At-Brahman Sahi, Old Town, Po- 2 Dr. Sudarsan Tripathy Nayagarh, Dist-Nayagarh, Pin- Nayagarh, Dist-Nayagarh, Pin- 752070 752070 2 At-Chandiagadi, Po-Malpatana, At-Chandiagadi, Po-Malpatana, 3 Dr. Pitamber Nath Sharma Dist-Cuttack Dist-Cuttack 3 Lokanath Ausadhalaya, At/Po- Lokanath Ausadhalaya, At/Po- 4 Dr. Baishnab Ch. Tripathy Bhawanipatna, Dist-Kalahandi, Bhawanipatna, Dist-Kalahandi, 766001 766001 4 At/Po-Ramachandrapur Sasan, At/Po-Ramachandrapur Sasan, 6 Dr. Narayan Panda Dist- Ganjam Dist- Ganjam 5 At/Po-Subarnapeta Street, Aska, At/Po-Subarnapeta Street, Aska, 8 Dr. Ganeswar Acharya Sharma Dist-GAnjam, 761110 Dist-GAnjam, 761110 6 At/Po-Chandanbhati, Dist-Bolangir At/Po-Chandanbhati, Dist-Bolangir 9 Dr. Bidyadhar Mishra 7 At-Malpara,Po/Via- Bolangir, At-Malpara,Po/Via- Bolangir, 13/ 66 Dr. Dasaratha Mishra Dist-Bolangir, 767001 Dist-Bolangir, 767001 8 At/Po-Parahat, Dist-Jagatsinghpur At/Po-Parahat, Dist-Jagatsinghpur 15/ 66 Dr. Atala Bhihari Panda 9 At-Agarkul, Po-Kortal, Dist- At-Agarkul, Po-Kortal, Dist- 24/ 66 Dr. Bansidhar Acharya Jagatsinghpur, 754103 Jagatsinghpur, 754103 10 At-Lenka Colony, College Square, At-Lenka Colony, College Square, 52/ 66 Dr. Chandrasekhar Mohapatra Po-Nuagaon, Via-Aska, Dist-Ganjam Po-Nuagaon, Via-Aska, Dist-Ganjam 11 At-Patrapur, Po-Badabramana Sahi, At-Patrapur, Po-Badabramana Sahi, 53/ 66 Dr. Banchhanidhi Pathy Dist-Ganjam Dist-Ganjam 12 At/Po-Goseingaon, Via-Boisinga, At/Po-Goseingaon, Via-Boisinga, 55/ 66 Dr. -

Mapping Bangladesh's Political Crisis

Mapping Bangladesh’s Political Crisis Asia Report N°264 | 9 February 2015 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Anatomy of a Conflict ....................................................................................................... 3 A. A Bitter History .......................................................................................................... 3 B. Democracy Returns ................................................................................................... 5 C. The Caretaker Model Ends ........................................................................................ 5 D. The 2014 Election ...................................................................................................... 6 III. Political Dysfunction ........................................................................................................ 8 A. Parliamentary Incapacity ........................................................................................... 8 B. An Opposition in Disarray ......................................................................................... 9 1. BNP Politics ......................................................................................................... -

India-Benin Relations

India-Benin Relations Political Relations: Benin and India have friendly ties characterised by democracy and secularism. Both the Indian and the Beninese sides recognised the urgent need for reform of the UN Security Council. The Beninese government reiterated its support for India's candidature for Permanent membership of an expanded UN Security Council. The current phase of ascendance in indo-Benin relations can be traced to the State visit to India on March 3-7, 2009 by President Boni Yayi accompanied by Madame Chantal Yayi and five ministers. In addition to plenary session with Prime Minister Dr Manmohan Singh, President Boni Yayi held bilateral meetings with President, Vice President and EAM. Hon’ble PM announced a Line of Credit $ 15mn for Benin. Two grants of one million dollar each for mutually identified projects in health and education sectors as well as establishment of IT Centre for Excellence and Centre of Demonstration of Technology (both on grant basis) were also agreed to. During the visit, five agreements were signed. During his official interactions, President Yayi appreciated India’s support to Africa and extended full support to India in her bid for permanent seat at the UN Security Council and in our struggle against terrorism. A group of Benin businessmen also accompanied the official delegation. Minister of State for External Affairs Dr Shashi Tharoor paid an official visit to Republic of Benin from October 21 to 23, 2009 and the first Meeting of the India-Benin Joint Commission on political, economic, scientific, technical and cultural cooperation was held at Cotonou. The JCM reviewed the entire gamut of bilateral relations and discussed various measures to strengthen bilateral ties. -

4 KALINGAINTERNATIONAL BUDDHIST CONCLAVE Udayagiri

Government of Odisha Department of Tourism & Culture (Tourism) 4TH KALINGA INTERNATIONAL BUDDHIST CONCLAVE Udayagiri | Bhubaneswar 10th - 12th April 2017 PRESS RELEASE With an objective to promote the Buddhist heritage of Odisha as a niche product within and outside the country the Department of Tourism has started organizing the International Conference on Buddhism in Udayagiri, Odisha since 2013. The idea is to bring to light the rich Buddhist heritage through scholastic deliberations and discussions inviting scholars, academicians, researchers, historians and above all the Tour Operators and Travel Agents from within and outside India to promote this glorious chapter of Odisha's history. Buddhism in Odisha is as old as the religion itself. It became the cradle of the newly emerging religion. Odisha had played a major role in converting Buddhism from a regional religion of north India to an international religion. It was at Dhauli that Emperor Ashoka's transformation from Chandashoka to Dharmashoka occurred after his embracing Buddhism. In the last two /three decades hundreds of Buddhist sites were explored and many of them were excavated in Odisha. It is revealed that number of huge Buddhist settlement sites like Lalitgiri, Udayagiri,Ratnagiri, Langudi, Radhanagar, Aragarh etc that all presents a scenic landscape, serene monumental remains (Stupas, Chaityas, Monasteries) and sublime metaphors (Buddha and Boddhisattavs) that tells the story of Odisha’s past of life and culture. This 4 th International Buddhist Conference is being organized at Udayagiri and Bhubaneswar from 10 th to 12 th April 2017 by Department of Tourism in association with Odishan Institute of Maritime and South East Asian Studies and Archaeological Survey of India in support of Odisha Tourism Development Corporation (OTDC) and Odisha Mining Corporation(OMC). -

635301449163371226 IIC ANNUAL REPORT 2013-14 5-3-2014.Pdf

2013-2014 2013 -2014 Annual Report IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE 2013-2014 IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE New Delhi Board of Trustees Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee, President Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna Professor M.G.K. Menon Mr. L.K. Joshi Dr. (Smt.) Kapila Vatsyayan Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Mr. N. N. Vohra Executive Members Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Professor Dinesh Singh Mr. K. Raghunath Dr. Biswajit Dhar Dr. (Ms) Sukrita Paul Kumar Cmde.(Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Cmde.(Retd.) C. Uday Bhaskar Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mrs. Meera Bhatia Finance Committee Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna, Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Chairman Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mr. M. Damodaran Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Cmde.(Retd.) C. Uday Bhaskar Mr. Ashok K. Chopra, Chief Finance Officer Medical Consultants Dr. K.P. Mathur Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. Gita Prakash Dr. Mohammad Qasim IIC Senior Staff Ms Omita Goyal, Chief Editor Mr. A.L. Rawal, Dy. General Manager Dr. S. Majumdar, Chief Librarian Mr. Vijay Kumar, Executive Chef Ms Premola Ghose, Chief, Programme Division Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance and Accounts Officer Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief, Maintenance Division Ms Hema Gusain, Purchase Officer Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Ms Seema Kohli, Membership Officer Annual Report 2013-2014 It is a privilege to present the 53rd Annual Report of the India International Centre for the period 1 February 2013 to 31 January 2014. The Board of Trustees reconstituted the Finance Committee for the two-year period April 2013 to March 2015 with Justice B.N. -

Indo-US Strategic Partnership: Are We There Yet?

IPCS Issue Brief 39 October 2006 INDO-US STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP ARE WE THERE YET? Lalit Mansingh Even though they shared common “Americans always do the right values, India and the United States thing,” said Winston Churchill, “after had divergent views on their they have tried everything else”. In the respective roles in the world. The US contest of India, it took the Americans saw itself as the leader of the Free five decades to do the right thing. World, fighting a crusade against the These were the five decades of the evil forces of international Cold War, described by the late communism. India had no such Senator Moynihan, a former American phobia against communism and Ambassador to India, as a “half preferred to remain non-Aligned. An century of misunderstandings, enduring image of the Cold War, in miscues, and mishaps. “Former Indian minds, is that of John Foster External Affairs Minister Jaswant Dulles, Eisenhower’s Secretary of Singh called them “the fifty wasted State. Issuing a fatwa against non- years”. Alignment, Dulles pronounced it immoral and declared it incompatible INDIA’S STRATEGIC1 with friendship with the United States. IRRELEVANCE TO THE UNITED STATES Dulles was reflecting what the US Joint Chief of Staff had concluded-that India was strategically irrelevant for Ambassador Mansingh is currently an the United States. Their ally of choice Executive Committee Member, IPCS. He in the region was Pakistan. As Dulles was earlier India’s Foreign Secretary and pursued his ‘Pactomania’ and got Indian Ambassador to the US. Pakistan admitted to CENTO and SEATO, the political distance between This paper was originally delivered as a Delhi and Washington continued to keynote address at the Army War College, grow.