Scaling India-Japan Cooperation in Indo-Pacific and Beyond 2025 Corridors, Connectivity and Contours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CURRICULUM VITAE Kenneth J. Ruoff Contact Information

CURRICULUM VITAE Kenneth J. Ruoff Contact Information: Department of History Portland State University P.O. Box 751 Portland, OR 97207-0751 Tel. (503) 725-3991 Fax. (503) 725-3953 e-mail: [email protected] http://web.pdx.edu/~ruoffk/ Education Ph.D. 1997 Columbia University History M.Phil. 1993 Columbia University History M.A. 1991 Columbia University History B.A. 1989 Harvard College East Asian Studies Study of advanced Japanese, Inter-University Center (formerly known as the Stanford Center), Yokohama, Japan, 1993-1994 (this is a non-degree program). Awards Tim Garrison Faculty Award for Historical Research, Portland State University, 2020. For Japan's Imperial House in the Postwar Era, 1945-2019. Ambassador, Hokkaido University, 2019-present. Branford Price Millar Award for Faculty Excellence, Portland State University, Spring 2015. For excellence in the areas of research and teaching, in particular, but also for community service. Commendation, Consulate General of Japan, Portland, OR, December 2014. For enriching the cultural landscape of Portland through programs sponsored by the Center for Japanese Studies and for improving the understanding of Japan both through these programs and through scholarship. Frances Fuller Victor Award for General Nonfiction (best work of nonfiction by an Oregon author), Oregon Book Awards sponsored by the Literary Arts Organization, 2012. For Imperial Japan at Its Zenith: The Wartime Celebration of the Empire’s 2,600th Anniversary. Jirõ Osaragi Prize for Commentary (in Japanese, the Osaragi Jirõ rondanshõ), 2004, awarded by the Asahi Newspaper Company (Asahi Shinbun) for the best book in the social sciences published in Japan during the previous year (For Kokumin no tennõ; translation of The People’s Emperor). -

MA Political Science Programme

Department of Political Science, University of Delhi UNIVERSITY OF DELHI MASTER OF ARTS in POLITICAL SCIENCE (M.A. in Political Science) (Effective from Academic Year 2019-20) PROGRAMME BROCHURE Revised Syllabus as approved by Academic Council on XXXX, 2019 and Executive Council on YYYY, 2019 Department of Political Science, University of Delhi 1 | Page Table of Contents I. About the Department ................................................................................................................ 3 1.1 About the Programme: ............................................................................................................. 4 1.2 About the Process of Course Development Involving Diverse Stakeholders .......................... 4 II. Introduction to CBCS (Choice Based Credit System) .............................................................. 5 III. M.A. Political Science Programme Details: ............................................................................ 6 IV. Semester wise Details of M.A.in Political Science Course....................................................... 9 4.1 Semester wise Details ................................................................................................................ 9 4.2 List of Elective Course (wherever applicable to be mentioned area wise) ............................ 10 4.3 Eligibility for Admission: ....................................................................................................... 13 4.4 Reservations/ Concessions: .................................................................................................... -

Long Diagnostic Delay with Unknown Transmission Route Inversely Correlates with the Subsequent Doubling Time of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Japan, February–March 2020

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Long Diagnostic Delay with Unknown Transmission Route Inversely Correlates with the Subsequent Doubling Time of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in Japan, February–March 2020 Tsuyoshi Ogata 1,* and Hideo Tanaka 2 1 Tsuchiura Public Health Center of Ibaraki Prefectural Government, Tsuchiura 300-0812, Japan 2 Fujiidera Public Health Center of Osaka Prefectural Government, Fujiidera 583-0024, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Long diagnostic delays (LDDs) may decrease the effectiveness of patient isolation in reducing subsequent transmission of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). This study aims to investigate the correlation between the proportion of LDD of COVID-19 patients with unknown transmission routes and the subsequent doubling time. LDD was defined as the duration between COVID-19 symptom onset and confirmation ≥6 days. We investigated the geographic correlation between the LDD proportion among 369 confirmed COVID-19 patients with symptom onset between the 9th and 11th week and the subsequent doubling time for 717 patients in the 12th–13th week among the six prefectures. The doubling time on March 29 (the end of the 13th week) ranged from 4.67 days in Chiba to 22.2 days in Aichi. Using a Pearson’s product-moment correlation (p-value = 0.00182) and multiple regression analyses that were adjusted for sex and age (correlation coefficient −0.729, 95% confidence interval: −0.923–−0.535, p-value = 0.0179), the proportion of LDD for unknown Citation: Ogata, T.; Tanaka, H. Long exposure patients was correlated inversely with the base 10 logarithm of the subsequent doubling Diagnostic Delay with Unknown time. -

International Conference TOWARDS a WORLD FREE of NUCLEAR

Programme As on May 28, 2008 International Conference on TOWARDS A WORLD FREE OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS June 9-10, 2008 Venue: Hotel Maurya ITC, New Delhi (Kamal Mahal) June 9, 2008 (Monday) 0830 Registration 0930-1100 Inaugural Session Welcome Remarks: Air Cmde Jasjit Singh AVSM VrC VM (retd) Director, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, New Delhi Keynote Address: Mr Sergio de Queiroz Duarte High Representative for Disarmament Affairs, United Nations Inaugural Address: Dr Manmohan Singh Prime Minister of India 1100-1130 Tea 1130-1330 Session I: Nuclear Weapons in the Contemporary World Chairman: Mr Lalit Mansingh Former Foreign Secretary st Relevance of Nuclear Deterrence in 21 Century - Dr Jonathan Granoff President, Global Security Initiative, USA Nuclear Weapons and International Terrorism - Dr Rajesh Rajagopalan 7 Professor, School of International Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Responsibilities of US and Russia in - Senator Douglas Roche Leading the Way to Nuclear Disarmament Former Chairman UN Disarmament Committee 1330-1430 Lunch 1430-1715 Session II: The Non Proliferation Challenge Chairman: Mr Richard Butler Chairman, Canberra Commission Need for a new Global Consensus on - Dr Sverre Lodgaard, Former Director, Norwegian Non-proliferation Institute of International Relations, Oslo Re-establishing the link between - Mr Rakesh Sood Non Proliferation and Nuclear Disarmament Ambassador of India to Nepal Non Proliferation in the Age of - Dr George Perkovich Civil Nuclear Renaissance Vice President, Global Security -

2009-2010, Eight Regular Meetings, Two Special Meetings of the Executive Council Were Held

GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009 -10 )0(V ANNUAL REPORT June 2009— May 2010 GOA UNIVERSITY TALEIGAO PLATEAU GOA 403 206 1 GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009-10 GOA UNIVERSITY CHANCELLOR H. E. Dr. S. S. Sidhu VICE-CHANCELLOR Prof. Dileep N. Deobagkar REGISTRAR Dr. M. M. Sangodkar GOA UNIVERSITY ANNUAL REPORT 2009 -10 CONTENTS Pg. No. Pg. No. PREFACE 4 PART 3: ACHIEVEMENTS OF UNIVERSITY INTRODUCTION 5 FACULTY PART 1: UNIVERSITY AUTHORITIES AND A: Seminars Organised 58 BODIES B: Papers Presented 61 1,1 Members of Executive Council 6 C: ' Research Publications 72 1.2 Members of University Court 6 D: Articles in Books 78 1.3 Members of Academic Council 8 E: Book Reviews 80 1.4 Members of Planning Board 9 F: Books/Monographs Published 80 G. Sponsored Consultancy 81 1.5 Members of Finance Committee 9 Ph.D. Awardees 82 1.6 Deans of Faculties 10 List of the Rankers (PG) 84 1.7 Officers of the University 10 PART 4: GENERAL ADMINISTRATION 1.8 Other Bodies/Associations and their 11 Composition General Information 85 Computerisation of University Functions 85 Part 2: UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENTS/ CENTRES / PROGRAMMES Conduct of Examinations 85 2.1 Faculty of Languages & Literature 13 Library 85 2.2 Faculty of Social Sciences 24 Sports 87 2.3 Faculty of Natural Sciences 31 Directorate of Students' Welfare & 88 Cultural Affairs 2.4 Faculty of Life Sciences & Environment 39 U.G.C. Academic Staff College 88 2.5 Faculty of Management Studies 51 Health Centre 89 2.6 Faculty of Commerce 52 College Development Council 89 2.7 Innovative Programmes 55 (i) Research -

'State Visit' of Shri KR Narayanan, President of the Republic of India To

1 ‘State Visit’ of Shri KR Narayanan, President of the Republic of India to Peru and Brazil from 26 Apr to 10 May 1998 COMPOSITION OF DELEGATION (I) President and Family 1. The President 2. The First Lady 3. 2 x Daughter of the President 4. Granddaughter of the President (II) President’s Secretariat Delegation 1. Shri Gopalkrishna Gandhi Secretary to the President 2. Shri SK Sheriff Joint Secretary to the President 3. Maj Gen Bhopinder Singh Military Secretary to the President 4. Shri TP Seetharam Press Secretary to the President 5. Dr NK Khadiya Physician, President’s Estate Clinic No. of auxiliary staff : 15 (III) Parliamentary Delegation 1. Shri Ananth Kumar Minister of Civil Aviation 2. Shri Bangaru Laxman Member of Parliament (RS) 3. Shri Murli Deora Member of Parliament (LS) No. of supporting staff : 01 2 (IV) Ministry of External Affairs Delegation 1. Shri K Raghunath Foreign Secretary, MEA (for New York only) 2. Shri Lalit Mansingh Secretary (West), MEA 3. Shri Alok Prasad Joint Secretary (AMS), MEA (For New York only) 4. Shri SM Gavai Chief of Protocol, MEA 5. Smt Homai Saha Joint Secretary (LAC), MEA No. of supporting staff : 04 (V) Security Staff Total : 19 (VI) Media Delegation 1. Ms Rizwana Akhtar Correspondent, Doordarshan 2. Shri Sanjay Bhatnagar Correspondent, Univarta 3. Shri Ramesh Chand Cameraman, ANI 4. Dr John Cherian World Affairs Correspondent, Frontline 5. Shri Subhasish Choudhary Chief Recordist, Films Division 6. Ms Seema Goswami Editor, Weekend Magazine, Anand Bazar Patrika 7. Shri Mahesh Kamble Chief Cameraman, Films Division 8. Shri KL Katyal Programme Executive, All India Radio 3 9. -

![Purbasa Conference[Initial].P65](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9942/purbasa-conference-initial-p65-1839942.webp)

Purbasa Conference[Initial].P65

PURBASA: EAST MEETS EAST Synergising the North-East and Eastern India with the Indo-Pacific PURBASA: EAST MEETS EAST Synergising the North-East and Eastern India with the Indo-Pacific Editors Lalit Mansingh Anup K. Mudgal Udai Bhanu Singh PENTAGON PRESS LLPLLP PURBASA: EAST MEETS EAST Synergising the North-East and Eastern India with the Indo-Pacific Editors: Lalit Mansingh, Anup K. Mudgal, Udai Bhanu Singh First Published in 2019 Copyright © Kalinga International Foundation (KIF) ISBN 978-93-86618-64-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without first obtaining written permission of the copyright owner. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Kalinga International Foundation (KIF), or the Government of India. Published by PENTAGON PRESS LLP 206, Peacock Lane, Shahpur Jat New Delhi-110049 Phones: 011-64706243, 26491568 Telefax: 011-26490600 email: [email protected] website: www.pentagonpress.in Printed at Avantika Printers Private Limited. Contents Preface ix Kalinga International Foundation xi Introduction xiii 1. Welcome Address 1 Lalit Mansingh 2. Inaugural Programme: Summary Report on the Proceedings 5 3. Vote of Thanks at the Kalinga International Foundation: Inaugural Session 9 Shreerupa Mitra ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION 4. India’s Economic Cooperation with East and Southeast Asia 15 V.S. Seshadri 5. Remarks by Ambassador of Vietnam 20 Ton Sinh Thanh 6. Economic Engagement and Connectivity between India’s North East and the Indo-Pacific 23 Anil Wadhwa 7. -

National Survey Report of Japan 2019

Task 1 Strategic PV Analysis and Outreach National Survey Report of PV Power Applications in JAPAN 2019 Prepared by: Mitsuhiro YAMAZAKI, New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) Osamu IKKI, RTS Corporation PVPS Task 1 – National Survey Report of PV Power Applications in JAPANNational Survey Report of Japan 2019 What is IEA PVPS TCP? The International Energy Agency (IEA), founded in 1974, is an autonomous body within the framework of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). The Technology Collaboration Programme (TCP) was created with a belief that the future of energy security and sustainability starts with global collaboration. The programme is made up of 6.000 experts across government, academia, and industry dedicated to advancing common research and the application of specific energy technologies . The IEA Photovoltaic Power Systems Programme (IEA PVPS) is one of the TCP’s within the IEA and was established in 1993. The mission of the programme is to “enhance the international collaborative efforts which facilitate the role of photovoltaic sol ar energy as a cornerstone in the transition to sustainable energy systems.” In order to achieve this, the Programme’s participants have undertaken a variety of joint research projects in PV power systems applications. The overall programme is headed by an Execu tive Committee, comprised of one delegate from each country or organisation member, which designates distinct ‘Tasks,’ that may be research projects or activity areas. The IEA PVPS participating countries are Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Chile, China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Italy, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, the Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, Turkey, and the United States of America. -

Dr Pathy Book.Pdf

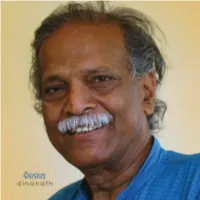

dinanath Published by Third Eye Communications A unit of Ketaki Enterprises Pvt. Ltd. N-4/252, IRC Village, Bhubaneswar Odisha. India 751015 E [email protected] With Support from IPCA ILa Panda Centre for Arts Bhubaneswar Dr. Dinanath Pathy left this material and world doing what he loved most; working for the cause of art and for Print-Tech Offset Pvt. Ltd. what he believed to be right. He left behind a vast expanse of memories and Bhubaneswar experiences which can never be filled in. In this publication we have earnestly tried Concept, Layout and Design to create the memories of the legendary Jyotiranjan Swain painter, writer and art philosopher Satyabhusan Hota through a collection of pictures. There are many more images and memories Photographs which could not be included due to limitations of time and immediate Ramahari Jena, A. Prathap, PC Dhir, availability of materials. We are looking Jyotiranjan Swain, Subrat Das, Sangram forward to touching other aspects of his Jena, Soubhagya Pathy, Abtin Javid, life in our future publications. IPCA, Angarag and Sutra Foundation Dr. Dinanath Pathy 1942-2016 Painter, Writer and Art Historian A distinguished practicing painter and pioneer of the Modern and Contemporary Art Movement of Odisha, Dr. Dinanath Pathy was brought up in a family of artists and poets in the traditional town of Digapahandi, Ganjam in Odisha. In education and training, he combined both traditional Guru-Sisya Parampara as well as the modern university system. He studied at Khallikote, Bhubaneswar, Santiniketan and Zurich. He wrote two dissertations: History of Orissan Painting, and Art and Regional Traditions. -

US-India Relations

The Sigur Center Asia Papers U.S.-India Relations: Ties That Bind? by Deepa Ollapally Previous Issues 22.U.S.-India Relations: Ties That Bind? China: A Preliminary Analysis Deepa Ollapally, 2005 Ren Xiao, 2000 21. India-China Relations in the Context of Vajpayee’s 8. Creation and Re-Creation: Modern Korean Fiction and 2003 Visit Its Translation Surjit Mansingh, 2005 Young-Key Kim-Renaud, and R. Richard Grinker, eds., 20. Korean American Literature 2000 Young-Key Kim-Renaud, R. Richard Grinker, and Kirk W. 7. Trends in China Watching: Observing the PRC at 50 Larsen, eds., 2004 Bruce Dickson, ed., 1999 19. Sorrows of Empire: Imperialism, Militarism, and the 6. US-Japan Relations in an Era of Globalization End of the Republic Mike M. Mochizuki, 1999 Chalmers Johnson, 2004 5. Southeast Asian Countries’ Perceptions of China’s 18. Europe and America in Asia: Different Beds, Same Military Modernization Dreams Koong Pai Ching, 1999 Michael Yahuda, 2004 4. Enhancing Sino-American Military Relations 17. Text and Context of Korean Cinema: Crossing Borders David Shambaugh, 1998 Young-Key Kim-Renaud, R. Richard Grinker, and Kirk W. 3. The Redefinition of the US-Japan Security Alliance and Larsen, eds., 2003 Its Implications for China 16. Korean Music Xu Heming, 1998 Young-Key Kim-Renaud, R. Richard Grinker, and Kirk W. 2. Is China Unstable? Assessing the Factors* Larsen, eds., 2002 David Shambaugh, ed., 1998 15. European and American Approaches Toward China: 1. International Relations in Asia: Culture, Nation, and Different Beds, Same Dreams? State David Shambaugh, 2002 Lucian W. Pye, 1998 14. -

The Jump to Organic Agriculture in Japan Lessons from Tea, Denmark, and Grassroots Movements

The jump to organic agriculture in Japan Lessons from tea, Denmark, and grassroots movements Rural Sociology group/ Shigeru Yoshida (580303980100)/ MSc Organic Agriculture Chair group: Rural Sociology Name: Shigeru Yoshida (580303980100) Study program: MSc Organic Agriculture Specialization: Sustainable food systems Code: RSO80436 Short title: The Jump to organic agriculture in Japan Date of submission: 16/04/2020 Abstract This research aims to clarify the reasons for the slow growth of organic farming in Japan and proposes possible government interventions to accelerate it. First, organic tea farming, which has increased exceptionally, is investigated. Second, a comparison between the organic market and governmental support for organics in Japan and Denmark is made. Denmark has the highest share of organic food relative to conventional food in the world. Finally, local organic markets emerging recently as a grassroots movement in local areas are investigated. This research found that the rapid increase of organic tea production is clearly led by a growing export market that increased the demand for organic products. In contrast, the domestic organic market is small because the Japanese consumers have not a strong motivation to buy organic foods due to the lack of awareness of organic agriculture. On the contrary, the Danish consumers are well aware that organic agriculture provides desired public goods. This is a result of government policies that have intervened at the demand side. The local organic markets in Japan may stimulate supermarkets to handle more organic products and coexist with them. I conclude that the national and local government interventions supporting market sectors, school-lunches, and the local organic market may result in an increase of consumer awareness, expansion of the organic market, and consequently, accelerating an increase in organic practices in Japan. -

Up-Dated Ay. Practitioners Voter List-2016.Xlsx

Up‐dated Voter List of Registered Practitioners under Odisha State Council of Ayurvedic Medicine, Bhubaneswar Regd. S.L Name of Regd. No./ Permanent Address Present Address No. Practitioners Year 1 At-Brahman Sahi, Old Town, Po- At-Brahman Sahi, Old Town, Po- 2 Dr. Sudarsan Tripathy Nayagarh, Dist-Nayagarh, Pin- Nayagarh, Dist-Nayagarh, Pin- 752070 752070 2 At-Chandiagadi, Po-Malpatana, At-Chandiagadi, Po-Malpatana, 3 Dr. Pitamber Nath Sharma Dist-Cuttack Dist-Cuttack 3 Lokanath Ausadhalaya, At/Po- Lokanath Ausadhalaya, At/Po- 4 Dr. Baishnab Ch. Tripathy Bhawanipatna, Dist-Kalahandi, Bhawanipatna, Dist-Kalahandi, 766001 766001 4 At/Po-Ramachandrapur Sasan, At/Po-Ramachandrapur Sasan, 6 Dr. Narayan Panda Dist- Ganjam Dist- Ganjam 5 At/Po-Subarnapeta Street, Aska, At/Po-Subarnapeta Street, Aska, 8 Dr. Ganeswar Acharya Sharma Dist-GAnjam, 761110 Dist-GAnjam, 761110 6 At/Po-Chandanbhati, Dist-Bolangir At/Po-Chandanbhati, Dist-Bolangir 9 Dr. Bidyadhar Mishra 7 At-Malpara,Po/Via- Bolangir, At-Malpara,Po/Via- Bolangir, 13/ 66 Dr. Dasaratha Mishra Dist-Bolangir, 767001 Dist-Bolangir, 767001 8 At/Po-Parahat, Dist-Jagatsinghpur At/Po-Parahat, Dist-Jagatsinghpur 15/ 66 Dr. Atala Bhihari Panda 9 At-Agarkul, Po-Kortal, Dist- At-Agarkul, Po-Kortal, Dist- 24/ 66 Dr. Bansidhar Acharya Jagatsinghpur, 754103 Jagatsinghpur, 754103 10 At-Lenka Colony, College Square, At-Lenka Colony, College Square, 52/ 66 Dr. Chandrasekhar Mohapatra Po-Nuagaon, Via-Aska, Dist-Ganjam Po-Nuagaon, Via-Aska, Dist-Ganjam 11 At-Patrapur, Po-Badabramana Sahi, At-Patrapur, Po-Badabramana Sahi, 53/ 66 Dr. Banchhanidhi Pathy Dist-Ganjam Dist-Ganjam 12 At/Po-Goseingaon, Via-Boisinga, At/Po-Goseingaon, Via-Boisinga, 55/ 66 Dr.