The New Astronomy the New Astronomy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Magnificent Spiral Galaxy Is Being Stretched by Passing Neighbor 27 May 2021, by Ray Villard

Magnificent spiral galaxy is being stretched by passing neighbor 27 May 2021, by Ray Villard animals—the gingham dog and calico cat—who got into a spat and ate each other. It's not so dramatic in this case. The galaxies are only getting a little chewed up because of their close proximity. The magnificent spiral galaxy NGC 2276 looks a bit lopsided in this Hubble Space Telescope snapshot. A bright hub of older yellowish stars normally lies directly in the center of most spiral galaxies. But the bulge in NGC 2276 looks offset to the upper left. What's going on? In reality, a neighboring galaxy to the right of NGC 2276 (NGC 2300, not seen here) is gravitationally tugging on its disk of blue stars, pulling the stars on one side of the galaxy outward to distort the galaxy's normal fried-egg appearance. This sort of "tug of war" between galaxies that pass close enough to feel each other's gravitational pull is not uncommon in the universe. But, like Credit: NASA, ESA, STScI, Paul Sell (University of snowflakes, no two close encounters look exactly Florida) alike. In addition, newborn and short-lived massive stars form a bright, blue arm along the upper left edge of The myriad spiral galaxies in our universe almost NGC 2276. They trace out a lane of intense star all look like fried eggs. A central bulge of aging formation. This may have been triggered by a prior stars is like the egg yolk, surrounded by a disk of collision with a dwarf galaxy. -

The Hot, Warm and Cold Gas in Arp 227 - an Evolving Poor Group R

The hot, warm and cold gas in Arp 227 - an evolving poor group R. Rampazzo, P. Alexander, C. Carignan, M.S. Clemens, H. Cullen, O. Garrido, M. Marcelin, K. Sheth, G. Trinchieri To cite this version: R. Rampazzo, P. Alexander, C. Carignan, M.S. Clemens, H. Cullen, et al.. The hot, warm and cold gas in Arp 227 - an evolving poor group. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Oxford University Press (OUP): Policy P - Oxford Open Option A, 2006, 368, pp.851. 10.1111/j.1365- 2966.2006.10179.x. hal-00083833 HAL Id: hal-00083833 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00083833 Submitted on 13 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 368, 851–863 (2006) doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10179.x The hot, warm and cold gas in Arp 227 – an evolving poor group R. Rampazzo,1 P. Alexander,2 C. Carignan,3 M. S. Clemens,1 H. Cullen,2 O. Garrido,4 M. Marcelin,5 K. Sheth6 and G. Trinchieri7 1Osservatorio Astronomico di Padova, Vicolo dell’Osservatorio 5, I-35122 Padova, Italy 2Astrophysics Group, Cavendish Laboratories, Cambridge CB3 OH3 3Departement´ de physique, Universite´ de Montreal,´ C. -

A Search For" Dwarf" Seyfert Nuclei. VII. a Catalog of Central Stellar

TO APPEAR IN The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. Preprint typeset using LATEX style emulateapj v. 26/01/00 A SEARCH FOR “DWARF” SEYFERT NUCLEI. VII. A CATALOG OF CENTRAL STELLAR VELOCITY DISPERSIONS OF NEARBY GALAXIES LUIS C. HO The Observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington, 813 Santa Barbara St., Pasadena, CA 91101 JENNY E. GREENE1 Department of Astrophysical Sciences, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ ALEXEI V. FILIPPENKO Department of Astronomy, University of California, Berkeley, CA 94720-3411 AND WALLACE L. W. SARGENT Palomar Observatory, California Institute of Technology, MS 105-24, Pasadena, CA 91125 To appear in The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. ABSTRACT We present new central stellar velocity dispersion measurements for 428 galaxies in the Palomar spectroscopic survey of bright, northern galaxies. Of these, 142 have no previously published measurements, most being rela- −1 tively late-type systems with low velocity dispersions (∼<100kms ). We provide updates to a number of literature dispersions with large uncertainties. Our measurements are based on a direct pixel-fitting technique that can ac- commodate composite stellar populations by calculating an optimal linear combination of input stellar templates. The original Palomar survey data were taken under conditions that are not ideally suited for deriving stellar veloc- ity dispersions for galaxies with a wide range of Hubble types. We describe an effective strategy to circumvent this complication and demonstrate that we can still obtain reliable velocity dispersions for this sample of well-studied nearby galaxies. Subject headings: galaxies: active — galaxies: kinematics and dynamics — galaxies: nuclei — galaxies: Seyfert — galaxies: starburst — surveys 1. INTRODUCTION tors, apertures, observing strategies, and analysis techniques. -

X-Ray Luminosities for a Magnitude-Limited Sample of Early-Type Galaxies from the ROSAT All-Sky Survey

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 302, 209±221 (1999) X-ray luminosities for a magnitude-limited sample of early-type galaxies from the ROSAT All-Sky Survey J. Beuing,1* S. DoÈbereiner,2 H. BoÈhringer2 and R. Bender1 1UniversitaÈts-Sternwarte MuÈnchen, Scheinerstrasse 1, D-81679 MuÈnchen, Germany 2Max-Planck-Institut fuÈr Extraterrestrische Physik, D-85740 Garching bei MuÈnchen, Germany Accepted 1998 August 3. Received 1998 June 1; in original form 1997 December 30 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article/302/2/209/968033 by guest on 30 September 2021 ABSTRACT For a magnitude-limited optical sample (BT # 13:5 mag) of early-type galaxies, we have derived X-ray luminosities from the ROSATAll-Sky Survey. The results are 101 detections and 192 useful upper limits in the range from 1036 to 1044 erg s1. For most of the galaxies no X-ray data have been available until now. On the basis of this sample with its full sky coverage, we ®nd no galaxy with an unusually low ¯ux from discrete emitters. Below log LB < 9:2L( the X-ray emission is compatible with being entirely due to discrete sources. Above log LB < 11:2L( no galaxy with only discrete emission is found. We further con®rm earlier ®ndings that Lx is strongly correlated with LB. Over the entire data range the slope is found to be 2:23 60:12. We also ®nd a luminosity dependence of this correlation. Below 1 log Lx 40:5 erg s it is consistent with a slope of 1, as expected from discrete emission. -

7.5 X 11.5.Threelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19267-5 - Observing and Cataloguing Nebulae and Star Clusters: From Herschel to Dreyer’s New General Catalogue Wolfgang Steinicke Index More information Name index The dates of birth and death, if available, for all 545 people (astronomers, telescope makers etc.) listed here are given. The data are mainly taken from the standard work Biographischer Index der Astronomie (Dick, Brüggenthies 2005). Some information has been added by the author (this especially concerns living twentieth-century astronomers). Members of the families of Dreyer, Lord Rosse and other astronomers (as mentioned in the text) are not listed. For obituaries see the references; compare also the compilations presented by Newcomb–Engelmann (Kempf 1911), Mädler (1873), Bode (1813) and Rudolf Wolf (1890). Markings: bold = portrait; underline = short biography. Abbe, Cleveland (1838–1916), 222–23, As-Sufi, Abd-al-Rahman (903–986), 164, 183, 229, 256, 271, 295, 338–42, 466 15–16, 167, 441–42, 446, 449–50, 455, 344, 346, 348, 360, 364, 367, 369, 393, Abell, George Ogden (1927–1983), 47, 475, 516 395, 395, 396–404, 406, 410, 415, 248 Austin, Edward P. (1843–1906), 6, 82, 423–24, 436, 441, 446, 448, 450, 455, Abbott, Francis Preserved (1799–1883), 335, 337, 446, 450 458–59, 461–63, 470, 477, 481, 483, 517–19 Auwers, Georg Friedrich Julius Arthur v. 505–11, 513–14, 517, 520, 526, 533, Abney, William (1843–1920), 360 (1838–1915), 7, 10, 12, 14–15, 26–27, 540–42, 548–61 Adams, John Couch (1819–1892), 122, 47, 50–51, 61, 65, 68–69, 88, 92–93, -

Making a Sky Atlas

Appendix A Making a Sky Atlas Although a number of very advanced sky atlases are now available in print, none is likely to be ideal for any given task. Published atlases will probably have too few or too many guide stars, too few or too many deep-sky objects plotted in them, wrong- size charts, etc. I found that with MegaStar I could design and make, specifically for my survey, a “just right” personalized atlas. My atlas consists of 108 charts, each about twenty square degrees in size, with guide stars down to magnitude 8.9. I used only the northernmost 78 charts, since I observed the sky only down to –35°. On the charts I plotted only the objects I wanted to observe. In addition I made enlargements of small, overcrowded areas (“quad charts”) as well as separate large-scale charts for the Virgo Galaxy Cluster, the latter with guide stars down to magnitude 11.4. I put the charts in plastic sheet protectors in a three-ring binder, taking them out and plac- ing them on my telescope mount’s clipboard as needed. To find an object I would use the 35 mm finder (except in the Virgo Cluster, where I used the 60 mm as the finder) to point the ensemble of telescopes at the indicated spot among the guide stars. If the object was not seen in the 35 mm, as it usually was not, I would then look in the larger telescopes. If the object was not immediately visible even in the primary telescope – a not uncommon occur- rence due to inexact initial pointing – I would then scan around for it. -

Ngc Catalogue Ngc Catalogue

NGC CATALOGUE NGC CATALOGUE 1 NGC CATALOGUE Object # Common Name Type Constellation Magnitude RA Dec NGC 1 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:07:16 27:42:32 NGC 2 - Galaxy Pegasus 14.2 00:07:17 27:40:43 NGC 3 - Galaxy Pisces 13.3 00:07:17 08:18:05 NGC 4 - Galaxy Pisces 15.8 00:07:24 08:22:26 NGC 5 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:07:49 35:21:46 NGC 6 NGC 20 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 7 - Galaxy Sculptor 13.9 00:08:21 -29:54:59 NGC 8 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:08:45 23:50:19 NGC 9 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.5 00:08:54 23:49:04 NGC 10 - Galaxy Sculptor 12.5 00:08:34 -33:51:28 NGC 11 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.7 00:08:42 37:26:53 NGC 12 - Galaxy Pisces 13.1 00:08:45 04:36:44 NGC 13 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.2 00:08:48 33:25:59 NGC 14 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.1 00:08:46 15:48:57 NGC 15 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.8 00:09:02 21:37:30 NGC 16 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:04 27:43:48 NGC 17 NGC 34 Galaxy Cetus 14.4 00:11:07 -12:06:28 NGC 18 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:09:23 27:43:56 NGC 19 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.3 00:10:41 32:58:58 NGC 20 See NGC 6 Galaxy Andromeda 13.1 00:09:33 33:18:32 NGC 21 NGC 29 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 22 - Galaxy Pegasus 13.6 00:09:48 27:49:58 NGC 23 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.0 00:09:53 25:55:26 NGC 24 - Galaxy Sculptor 11.6 00:09:56 -24:57:52 NGC 25 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.0 00:09:59 -57:01:13 NGC 26 - Galaxy Pegasus 12.9 00:10:26 25:49:56 NGC 27 - Galaxy Andromeda 13.5 00:10:33 28:59:49 NGC 28 - Galaxy Phoenix 13.8 00:10:25 -56:59:20 NGC 29 See NGC 21 Galaxy Andromeda 12.7 00:10:47 33:21:07 NGC 30 - Double Star Pegasus - 00:10:51 21:58:39 -

XMM Observations of an 1X0 in NGC 2276

XMM Observations of an 1x0 in NGC 2276 David S. and Richard F. Mushotzky3 ABSTRACT We present the results from a -53 ksec XMM observation of NGC 2276. This galaxy has an unusual optical morphology with the disk of this spiral appearing to be truncated along the western edge. This XMM observation shows that the X-ray source at the western edge is a bright Intermediate X-ray Object (1x0). Its spectrum is well fit by a multi-color disk blackbody model used to fit optically thick standard accretion disks around black holes. The luminosity derived for this 1x0 is 1.1~10~'erg s-l in the 0.5 - 10 keV band making it one of the most luminous discovered to date. The large source luminosity implies a large mass black hole if the source is radiating at the Eddington rate. On the other hand, the inner disk temperature determined here is too high for such a massive object given the standard accretion disk model. In addition to the 1x0 we find that the nuclear source in this galaxy has dimmed by at least a factor of several thousand in the eight years since the ROSAT HRI observations. Subject headings: Galaxies: spiral, x-ray - X-rays: galaxies 1. Introduction A new class of X-ray emitting objects has recently been revealed in nearby galaxies which are more luminous than normal X-ray binaries or supernova remnants but do not attain the luminosities of conventional AGN. These objects (intermediate luminosity objects: IXOs, Ptak 2002; ultraluminous X-ray sources: ULXs, Makishima et al. -

The Case of the Starburst Spiral NGC 2276

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 370, 453–467 (2006) doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2006.10492.x Gas stripping in galaxy groups – the case of the starburst spiral NGC 2276 Jesper Rasmussen,1⋆ Trevor J. Ponman1 and John S. Mulchaey2 1School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT 2Observatories of the Carnegie Institution, 813 Santa Barbara Street, Pasadena, CA 91101, USA Accepted 2006 April 26. Received 2006 April 26; in original form 2006 January 11 ABSTRACT Ram-pressure stripping of galactic gas is generally assumed to be inefficient in galaxy groups due to the relatively low density of the intragroup medium (IGM) and the small velocity disper- sions of groups. To test this assumption, we obtained Chandra X-ray data of the starbursting spiral NGC 2276 in the NGC 2300 group of galaxies, a candidate for a strong galaxy interaction with hot intragroup gas. The data reveal a shock-like feature along the western edge of the galaxy and a low surface brightness tail extending to the east, similar to the morphology seen in other wavebands. Spatially resolved spectroscopy shows that the data are consistent with intragroup gas being pressurized at the leading western edge of NGC 2276 due to the galaxy moving supersonically through the IGM at a velocity 850 km s 1. Detailed modelling of the ∼ − gravitational potential of NGC 2276 shows that the resulting ram pressure could significantly affect the morphology of the outer gas disc but is probably insufficient to strip large amounts of cold gas from the disc. We estimate the mass-loss rates due to turbulent viscous stripping and starburst outflows being swept back by ram pressure, showing that both mechanisms could plausibly explain the presence of the X-ray tail. -

Astronomy Magazine 2020 Index

Astronomy Magazine 2020 Index SUBJECT A AAVSO (American Association of Variable Star Observers), Spectroscopic Database (AVSpec), 2:15 Abell 21 (Medusa Nebula), 2:56, 59 Abell 85 (galaxy), 4:11 Abell 2384 (galaxy cluster), 9:12 Abell 3574 (galaxy cluster), 6:73 active galactic nuclei (AGNs). See black holes Aerojet Rocketdyne, 9:7 airglow, 6:73 al-Amal spaceprobe, 11:9 Aldebaran (Alpha Tauri) (star), binocular observation of, 1:62 Alnasl (Gamma Sagittarii) (optical double star), 8:68 Alpha Canum Venaticorum (Cor Caroli) (star), 4:66 Alpha Centauri A (star), 7:34–35 Alpha Centauri B (star), 7:34–35 Alpha Centauri (star system), 7:34 Alpha Orionis. See Betelgeuse (Alpha Orionis) Alpha Scorpii (Antares) (star), 7:68, 10:11 Alpha Tauri (Aldebaran) (star), binocular observation of, 1:62 amateur astronomy AAVSO Spectroscopic Database (AVSpec), 2:15 beginner’s guides, 3:66, 12:58 brown dwarfs discovered by citizen scientists, 12:13 discovery and observation of exoplanets, 6:54–57 mindful observation, 11:14 Planetary Society awards, 5:13 satellite tracking, 2:62 women in astronomy clubs, 8:66, 9:64 Amateur Telescope Makers of Boston (ATMoB), 8:66 American Association of Variable Star Observers (AAVSO), Spectroscopic Database (AVSpec), 2:15 Andromeda Galaxy (M31) binocular observations of, 12:60 consumption of dwarf galaxies, 2:11 images of, 3:72, 6:31 satellite galaxies, 11:62 Antares (Alpha Scorpii) (star), 7:68, 10:11 Antennae galaxies (NGC 4038 and NGC 4039), 3:28 Apollo missions commemorative postage stamps, 11:54–55 extravehicular activity -

October 2020 BRAS Newsletter

A Neowise Comet 2020, photo by Ralf Rohner of Skypointer Photography Monthly Meeting October 12th at 7:00 PM, via Jitsi (Monthly meetings are on 2nd Mondays at Highland Road Park Observatory, temporarily during quarantine at meet.jit.si/BRASMeets). GUEST SPEAKER: Tom Field, President of Field Tested Systems and Contributing Editor for Sky & Telescope Magazine. His presentation is on Astronomical Spectra. What's In This Issue? President’s Message Secretary's Summary Business Meeting Minutes Outreach Report Asteroid and Comet News Light Pollution Committee Report Globe at Night Astro-Photos by BRAS Members Messages from the HRPO REMOTE DISCUSSION Solar Viewing Great Martian Opposition Uranian Opposition Lunar Halloween Party Edge of Night Observing Notes: Cepheus – The King Like this newsletter? See PAST ISSUES online back to 2009 Visit us on Facebook – Baton Rouge Astronomical Society BRAS YouTube Channel Baton Rouge Astronomical Society Newsletter, Night Visions Page 2 of 27 October 2020 President’s Message Happy October. I hope everybody has been enjoying this early cool front and the taste of fall that comes with it. More to our interests, I hope everybody has been enjoying the longer evenings thanks to our entering Fall. Soon, those nights will start even earlier as Daylight Savings time finally ends for the year— unfortunately, it may be the last Standard Time for some time. Legislation passed over the summer will mandate Louisiana doing away with Standard time if federal law allows, and a bill making it’s way through the US senate right not aims to do just that: so, if you prefer earlier sunsets, take the time to write your congressmen before it’s too late. -

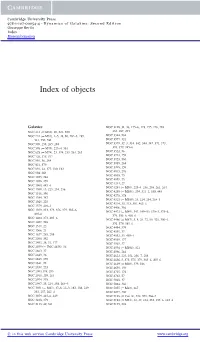

Index of Objects

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-00054-4 - Dynamics of Galaxies: Second Edition Giuseppe Bertin Index More information Index of objects Galaxies NGC 3198, 31, 36, 175–6, 178, 255, 276, 283, NGC 221 (= M32), 20, 321, 350 285, 287, 293 NGC 224 (= M31), 4–5, 48, 80, 282–3, 289, NGC 3344, 264 321, 350, 381 NGC 3377, 321 NGC 309, 258, 265, 288 NGC 3379, 32–3, 314, 342, 344, 347, 371, 373, NGC 598 (= M33), 223–4, 381 376, 379, 385–6 NGC 628 (= M74), 23, 174, 259, 261, 265 NGC 3521, 36 NGC 720, 375, 377 NGC 3741, 259 NGC 801, 36, 284 NGC 3923, 386 NGC 821, 379 NGC 3938, 264 NGC 3998, 159 NGC 891, 24, 177, 180, 182 NGC 4013, 276 NGC 936, 264 NGC 4038, 75 NGC 1035, 284 NGC 4039, 75 NGC 1058, 259 NGC 4244, 27 NGC 1068, 445–6 NGC 4254 (= M99), 223–4, 256, 258, 261, 264 NGC 1300, 13, 225, 254, 256 NGC 4258 (= M106), 294, 321–2, 350, 445 NGC 1316, 386 NGC 4278, 378 NGC 1344, 387 NGC 4321 (= M100), 23, 224, 254, 264–5 NGC 1365, 225 NGC 4374, 33, 373, 387, 405–6 NGC 1379, 410–1 NGC 4406, 386 NGC 1399, 351, 373, 376, 379, 385–6, NGC 4472 (= M49), 347, 349–50, 370–3, 375–6, 405–6 379, 385–6, 405–6 NGC 1404, 373, 405–6 NGC 4486 (= M87), 5, 8, 20, 72, 80, 321, 350–1, NGC 1407, 388 376, 379, 385–6 NGC 1549, 22 NGC 4494, 379 NGC 1566, 21 NGC 4550, 37 NGC 1637, 265, 288 NGC 4552, 33, 410–1 NGC 2300, 382 NGC 4559, 177 NGC 2403, 28, 31, 177 NGC 4565, 27 = NGC 2599 ( UGC 4458), 36 NGC 4594 (= M104), 321 NGC 2663, 37 NGC 4596, 264 NGC 2683, 36 NGC 4622, 223, 254, 256–7, 288 NGC 2685, 159 NGC 4636, 5, 373, 375, 379, 385–6, 405–6 NGC 2841, 22 NGC 4649 (= M60),