The Alienated Clara: Intersectionality Perspectives in Adrienne Kennedy’S the Owl Answers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Women's Fiction and the Abject In

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses July 2018 WRITING NEW BOUNDARIES FOR THE LAW: BLACK WOMEN’S FICTION AND THE ABJECT IN PSYCHOANALYSIS Angelique Warner U Massachussetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Literature in English, North America, Ethnic and Cultural Minority Commons Recommended Citation Warner, Angelique, "WRITING NEW BOUNDARIES FOR THE LAW: BLACK WOMEN’S FICTION AND THE ABJECT IN PSYCHOANALYSIS" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1303. https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1303 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WRITING NEW BOUNDARIES FOR THE LAW: BLACK WOMEN’S FICTION AND THE ABJECT IN PSYCHOANALYSIS A Dissertation Presented by ANGELIQUE WARNER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2018 W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies © Angelique Warner 2018 All Rights Reserved WRITING NEW BOUNDARIES FOR THE LAW: BLACK WOMEN’s FICTION AND THE ABJECT IN PSYCHOANALYSIS A Dissertation Presented by ANGELIQUE WARNER Approved as to style and content by: James Smethurst, Chair Manisha Sinha, Member TreAndrea Russworm, Member Priscilla Page, Member Amilcar Shabazz, Department Head W.E.B. Du Bois Department of Afro-American Studies DEDICATION For Octavia Butler ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, James Smethurst, for his years of encouragement and his expertise in an area of literature that is so important to me. -

She Who Is Adrienne Kennedy and the Drama of Difference

She Who Is Adrienne Kennedy and the Drama of Difference Curated by Hilton Als and Artists Space Artists Space celebrates the singular vision of 88-year-old playwright Adrienne Kennedy February 29 – March 29, 2020 through a series of live performances, readings, screenings, and an exhibition of archival materials that transforms the building’s lower level into a theater and exhibition in homage to Kennedy’s radical vision. The multi-format program engages with the stories, literary figures, movies, and historical events that continue to inspire the playwright’s groundbreaking work, her plays boldly defying modernism’s trajectory by actively blending and juxtaposing unlikely voices and tones, these startling multiplicities often located within single shifting characters. In their brutal eloquence, Kennedy’s plays draw from a diverse set of mythological, historical, and geographic references to constitute and re-constitute blackness against the violent forces that have historically demarcated its ambivalent shape. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Ohio-raised Kennedy came to New York in 1954. After a transformative sea voyage and stay in Africa and Europe with her family, Kennedy returned to New York where her first drama, Funnyhouse of a Negro, was finally produced in 1964 with the mentorship of the legendary playwright Edward Albee. The show earned Kennedy an Obie for best play, and she became known to the artists and writers who frequented La MaMa and other experimental venues where the writer’s early scripts were realized. During those years, Kennedy stood apart from the burgeoning Black Arts Movement, which encouraged the making of revolutionary plays for black audiences. -

Dutchman the Owl Answers

Dutchman By Amiri Baraka (LeRoi Jones) Directed by Lou Bellamy and The Owl Answers By Adrienne Kennedy Directed by Talvin Wilks A Penumbra Theatre Company Production March 3-27, 2016 ©2016 Penumbra Theatre Company Dutchman and The Owl Answers Penumbra’s 2015-2016 Season: Revolution Love A Letter from the Co-Artistic Directors Lou Bellamy and Sarah Bellamy The African American experience reveals unique insight into the triumphs and tribulations of humankind. At the core of black identity we find remarkable resilience and an unwavering commitment to social justice. We stand on the shoulders of giants — a proud legacy of millions who fought to survive and who kept the flame alive for the next generation. Some names we know and celebrate every year, others go unrecognized by the history books but are remembered and honored in the drumming of our hearts. Change does not happen overnight, or even in the life cycle of one generation. Progress is made in fits and starts but only through collective action do we see real advancement. This season Penumbra offers you the opportunity to get involved. Hear from the very people who founded movements that shaped history, talk with local leaders, and meet others like yourself who love theatre and believe deeply in justice. At Penumbra, transformative art illuminates ways to move humanity forward with compassion – join us as we move from empathy to action, from emotion to solution. Ours is a brave, honest, intelligent, responsible, and hopeful community and there is a place for you here. Welcome. ©2016 -

Black Playwrights and Authors Became a Bestseller

Angelou, and Miller Williams; her poem, “Praise Song for the Day,” Black Playwrights and Authors became a bestseller. Ron Allen (playwright) – was an African American poet and playwright who described his work as a “concert of language.” Allen’s Looking for ways to incorporate Black History Month into early works included Last Church of the Twentieth Century, Aboriginal your classroom? Below is an initial list of works from nearly Treatment Center, Twenty Plays in Twenty Minutes, Dreaming the 100 Black authors, compiled in partnership with Wiley Reality Room Yellow, WHAM!, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Relative College. If there is a work you believe should be included Energy Sack Theory Museum, and The Heidelberg Project: Squatting here, please email [email protected]. in the Circle of the Elder Mind. After his move to Los Angeles, CA in 2007, Allen wrote three more plays: Swallow the Sun, My Eyes Are the Cage in My Head, and The Hieroglyph of the Cockatoo. Allen published books of critically acclaimed poetry, including I Want My Body Back and Neon Jawbone Riot. He released a book of poetry in 2008 titled The Inkblot Theory. Garland Anderson (playwright) – (February 18, 1886 – June 1, 1939) An African American playwright and speaker. After having a full- length drama on Broadway, Anderson gave talks on empowerment A and success largely related to the New Thought movement. Elizabeth Alexander (poet) – Elizabeth Alexander was born in Harlem, • Garland Anderson (1925). From Newsboy and Bellhop to New York, but grew up in Washington, D.C., the daughter of former Playwright. -

Pretending to Be Lincoln: Interracial Masquerades in Suzan-Lori Parks's

RSA JOU R N A L 24/2013 DANIELA DANIELE Pretending to Be Lincoln: Interracial Masquerades in Suzan-Lori Parks’s Twin Plays1 1. History Games at Play Adrienne Kennedy was the first playwright of African descent who staged black imitations of white leaders as ghostly figures emerging from the American political unconscious. The Owl Answers features African- American impersonators of Shakespeare, William the Conqueror, Geof- frey Chaucer, and Anne Boleyn, whose authority haunts a dream-like stage dominated by the dramatist’s distressed alter-egoes (Sollors 30). Kennedy’s anachronistic use of masquerade in whiteface was her parodic device to stress the subaltern identification of men and women of color with non- black icons. Suzan-Lori Parks also confronts the loss at the heart of the black experi- ence as “the great hole. In the middle of nowhere” (The America Play 158) and resurrects representative figures randomly selected from the Western literary canon and from the white political scene whose authority she ques- tions without fearing. Digging into the pitch black of the African-Ameri- can unconscious severely disrupted by slavery, Parks metaphorically resur- faces a burial heap of nameless bones that she identifies with her ancestry.2 As a result, in The America Play (1994), which, in many respects, is a black parody of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, her alter-ego is neither the fool nor the Danish prince but a black undertaker who meditates upon Yorick’s bones inherited from a white tradition lost to his memory.3 Like young Brazil in her first Lincoln play, the dramatist is “The Lesser Known .. -

Adrienne Kennedy

Adrienne Kennedy: An Inventory of Her Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator Kennedy, Adrienne, 1931- Title Adrienne Kennedy Papers circa 1954-1997 Dates: circa 1954-1997 Extent 12 boxes, 4 oversize folders (osf) (5.04 linear feet) Abstract The papers document Kennedy's evolution from an aspiring writer to a successful playwright, and include manuscripts for plays, short stories, memoirs, and novels, though film and television projects are also present. The papers also contain correspondence, manuscripts and publications about Kennedy, production materials from her plays, and sound and video recordings. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-00067 Language English. Access Open for research. Researchers must create an online Research Account and agree to the Materials Use Policy before using archival materials. Use Policies: Ransom Center collections may contain material with sensitive or confidential information that is protected under federal or state right to privacy laws and regulations. Researchers are advised that the disclosure of certain information pertaining to identifiable living individuals represented in the collections without the consent of those individuals may have legal ramifications (e.g., a cause of action under common law for invasion of privacy may arise if facts concerning an individual's private life are published that would be deemed highly offensive to a reasonable person) for which the Ransom Center and The University of Texas at Austin assume no responsibility. Restrictions on Authorization for publication is given on behalf of the University of Use: Texas as the owner of the collection and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder which must be obtained by the researcher. -

Play Scripts (PDF)

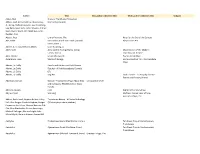

Author Title One-author collection title Multi-author collection title Subject Abbot, Rick Dracula, The Musical? (musical) Abbott, Bud; Allen, Ralph G.; Blount, Roy, Diamonds (musical) Jr.; Camp, Richard; Costello, Lou; Eisenberg, Lee; Kelly, Sean; Lahr, John; Masella, Arthur; Stein, Harry; Wann, Jim; Weidman, John; Zweibel, Alan Abdoh, Reza Law of Remains, The Plays for the End of the Century Abe, Kobo Man Who Turned into a Stick (Donald Plays in One Act Keene, trans.) Abeille, A. K.; David Manos Morris Little Haunting, A Abell, Kjeld Anna Sophie Hedvig (Hanna Astrup Masterpieces of the Modern Larsen, trans.) Scandinavian Theatre Abse, Dannie House of Cowards Twelve Great Plays Ackermann, Joan Stanton's Garage Humana Festival '93 - The Complete Plays Adams, Liz Duffy Poodle with Guitar and Dark Glasses Adams, Liz Duffy Dog Act - A Post-Apocalyptic Comedy Adams, Liz Duffy OR, Adams, Liz Duffy Dog Act Geek Theater - 15 Plays by Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Adamson, Samuel Decade - Twenty New Plays About 9/11 see Goold on shelf and Its Legacy: Recollections of Scott Forbes Addison, Joseph Cato Eighteenth Century Plays Adjimi, David Stunning Methuen Drama Book of New American Plays, The Adkins, Keith Josef; Stephen Belber; Hilary Trepidation Nation - A Phobic Anthology Bell; Glen Berger; Sheila Callaghan; Bridget (16 short plays about phobias) Carpenter; Cusi Cram; Richard Dresser; Erik Ehn; Gina Gionfriddo; Kirsten Greenidge; Michael Hollinger; Warren Leight; Julie Marie Myatt; Victoria Stewart; James Still Aechylus Prometheus Bound -

Musical Theater Projects That Received NEA Funding

Nov 2018 Under the Freedom of Information Act, agencies are required to proactively disclose frequently requested records. Often the National Endowment for the Arts receives requests for examples of funded grant proposals for various disciplines. In response, the NEA is providing examples of the “Project Information” also called the ”narrative” for two successful Musical Theater projects that received NEA funding. The selected examples are not the entire funded grant proposal and only contain the grant narrative and selected portions. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. The following narratives have been selected as examples because they represent a diversity of project types and are well written. Although each project was funded by the NEA, please note that nothing should be inferred about the ranking of each application within its respective applicant pool. We hope that you will find these records useful as examples of well written narratives. However please keep in mind that because each project is unique, these narratives should be used as references, rather than templates. If you are preparing your own application and have any questions, please contact the appropriate program office. You may also find additional information regarding the grant application process on our website at Apply for a Grant | NEA . Musical Theater Ford’s Theatre Ragtime Penumbra Playwrights Horizons MT Bella 16-969320 Attachments-ATT20-Project_Information.pdf Ford's Theatre Society Ford's Theatre Project Information Major Project Activities: Under the leadership of Director Paul R. -

Weyward Macbeth Demonstrates, That Actors, Directors, and Writers Often Assume That They Are the First to See the Connections

1 Beginnings Figure S.1 Text from Macbeth, Scena Tertia, First Folio, 1623. NNewstok_Ch01.inddewstok_Ch01.indd 1 99/16/2009/16/2009 22:57:39:57:39 PPMM NNewstok_Ch01.inddewstok_Ch01.indd 2 99/16/2009/16/2009 22:57:41:57:41 PPMM 1 What Is a “Weyward” M ACBETH? Ayanna Thompson Let’s begin at the beginning, that is, at the first word—weyward. As Margreta de Grazia and Peter Stallybrass explain: In most editions of [Macbeth], the witches refer to themselves as the “weird sisters” [see Figure S.1], and editors provide a footnote associating the word with Old English wyrd or “fate.” But we look in vain to the Folio for such crea- tures. Instead we encounter the “weyward Sisters” and the “weyard Sisters”; it is of “these weyward Sisters” that Lady Macbeth reads in the letter from Macbeth, and it is of “the three weyward sisters” that Banquo dreams. (263) Wondering why editors choose “weird” instead of “wayward” as the modern gloss for “weyward,” de Grazia and Stallybrass note that “a simple vowel shift” transposes “the sisters from the world of witchcraft and prophecy . to one of perversion and vagrancy” (263). In thinking about the roles Macbeth has played—and continues to play—in American constructions and perfor- mances of race, we want to maintain the multiplicity and instability of the original text’s typography. Unlike other critical texts that seek to capitalize on the subversive potentials of perversity through an appropriation of “way- ward,” this collection recognizes the ambivalent nature of the racialized re-stagings, adaptations,