Regulatory Reform in Electricity, Domestic Ferries and Trucking Analyses the Institutional Set-Up and Use of Policy Instruments in Greece

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Early Booking ! Discount !

VENICE - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS ANCONA - CORFU - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS 2017 BARI - CORFU - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS EARLY BOOKING ! Discount ! NEW For ANEK Smart 20% Bonus Members! YEARS Crete • Chania • Heraklion www.anek.gr Aegean Islands r d ! S e e y o u o n b o a YEARS April 1967. The Cretan folk set the ground for ANEK LINES to conquer the Mediterranean Sea, for more than 50 continuous years. The deep respect for its people as well as its Greek roots is what makes ANEK LINES a great family whose goal is to serve and accommodate thousands of travelers with a state-of-the- art fleet by providing a travel-friendly experience to all. At the same time, ANEK LINES stands by the people of the land where it was founded, by sponsoring sport, cultural and academic projects as well as providing back to the community and those in need among us. ANEK LINES has a clear vision: 23 unique destinations Each one, an unforgettable experience for each and every single passenger. ANEK LINES. Comfort. Luxury. Professionalism. Always ready for a new trip, setting sail for new experiences. Book Online! www.anek.gr Let us welcome you to the world of ANEK LINES. Your pleasant and comfortable journey in the Adriatic and clear blue waters of the Aegean has just begun. The Mediterranean sun, the various unique routes, our constant offer of heartwarming hospitality as well as the experienced crew are all here and ready to help you discover carefree traveling. Enjoy the comfort and quality of your stay. taste our unique Mediterranean cuisine along with refreshing drinks. -

Financial Report ANEK LINES S.A

CONTENTS STATEMENT BY THE MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS .................................................................... 3 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS FOR THE FISCAL YEAR 2014 .............................................. 4 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT ............................................................................................................ 43 ANNUAL SEPARATE AND CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS OF 31ST DECEMBER 2017 .............. 50 STATEMENTS OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME ............................................................................................. 51 STATEMENTS OF FINANCIAL POSITION ...................................................................................................... 52 STATEMENTS OG CHANGE IN SHAREHOLDER’S EQUITY............................................................................. 53 CASH FLOW STATEMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 54 NOTES ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF FISCAL YEAR 2017 ................................................................. 55 1. General information for the Company and the Group ....................................................................... 56 2. Preparation basis of the financial statements .................................................................................... 57 3. Principal accounting policies .............................................................................................................. 62 -

Venice – Corfu

ANEK LINES ROUTES FROM ITALY TO CORFU SCHEDULE 2018 IMPORTANT NOTICE: TIMES ARE INDICATED ON LOCAL TIME! VENICE - IGOUMENITSA From 01/01/2018 to 19/05/2018 and from 29/09/2018 to 31/12/2018 Days VENICE Departure IGOUMENITSA Arrival(1) Wed, Sat, Sun 12:00 14:30 (1) The following day VENICE – CORFU - IGOUMENITSA From 20/05/2018 to 28/06/2018 and from 10/09/2018 to 28/09/2018 Days VENICE Departure CORFU Arrival IGOUMENITSA Arrival(1) Wed, Sat 12:00 - 14:30 Fri 12:00 13:45 15:00 (1) The following day *SUNDAY 23/09: VENICE (DEPARTURE 12:00) – IGOUMENITSA (ARRIVAL 14:30 24/09) – PATRAS (ARRIVAL 21:00 24/09) VENICE - IGOUMENITSA From 29/06/2018 to 09/09/2018 Days VENICE Departure IGOUMENITSA Arrival(1) Wed, Sat 12:00 14:30 (1) The following day ANCONA - IGOUMENITSA From 01/01/2018 to 28/06/2018 and from 10/09/2018 to 31/12/2018 Days ANCONA Departure IGOUMENITSA Arrival Tue, Wed, Thu, Fri 13:30 08:00(1) Sat, Sun 16:30 09:30(1) (1)The following day. WEDNESDAY 03/01, THURSDAY 04/01 & FRIDAY 05/01 ANCONA (DEP. 16:30) – IGOUM. (ARR. 09:30) – PATRAS (ARR. 15:00 THE FOLLOWING DAY) ANCONA – CORFU - IGOUMENITSA From 29/06/2018 to 09/09/2018 Days ANCONA Departure CORFU Arrival(1) IGOUMENITSA Arrival(1) Mon, Wed, Fri, Sun 13:30 - 06:30 13:30 05:30 06:45 Tue 16:30 - 09:30 15:00 07:00 08:15 Thu 16:30 - 09:30 13:30 - 06:30 Sat 16:30 - 09:30 (1)The following day. -

Ανεκ 2019 Annual Financi

CONTENTS STATEMENT BY THE MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ................................................................... 3 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS FOR THE FISCAL YEAR 2019 ............................................. 4 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT ........................................................................................................... 50 ANNUAL SEPARATE AND CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS OF 31ST DECEMBER 2019 ............ 57 STATEMENTS OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME ............................................................................................. 58 STATEMENTS OF FINANCIAL POSITION ...................................................................................................... 59 STATEMENTS OF CHANGE IN SHAREHOLDER’S EQUITY ............................................................................. 60 CASH FLOW STATEMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 61 NOTES ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF FISCAL YEAR 2019 ................................................................ 62 1. General information for the Company and the Group ...................................................................... 63 2. Preparation basis of the financial statement .................................................................................... 64 3. Principal accounting policies ............................................................................................................. 71 4. Segmental -

20161231 Notes Eng

CONTENTS STATEMENT BY THE MEMBERS OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS .................................................................... 3 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ......................................................................................... 4 FOR THE FISCAL YEAR 2016 .......................................................................................................................... 4 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT ............................................................................................................ 45 ANNUAL SEPARATE AND CONSOLIDATED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS AS OF 31ST DECEMBER 2016 .............. 48 STATEMENT OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME ............................................................................................... 49 STATEMENTS OF FINANCIAL POSITION ...................................................................................................... 50 STATEMENT OF CHANGE IN SHAREHOLDER’S EQUITY ............................................................................... 51 CASH FLOW STATEMENTS .......................................................................................................................... 52 NOTES ON THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS OF FISCAL YEAR 2016 ................................................................. 53 1. General information for the Company and the Group ....................................................................... 54 2. Preparation basis of the financial statements ................................................................................... -

WHY YOGA and SWIMMING? Yoga and Swimming Are a Perfect Combination

TRIP OVERVIEW Discover the stunning coastlines and crystal clear waters of one of Europe’s southernmost destinations with an unforgettable swimming and yoga holiday on the idyllic Greek island of Crete. From dramatic coastal cliffs to isolated coves, bays and beaches, the island is full of spectacular locations to explore and enjoy. Our base for the week is the remote coastal village of Porto Loutro, which can only be reached by boat, hiking or, of course, swimming! Hotel Porto Loutro on the Hill, offers space for our yoga practice and modern, comfortable rooms with sea views. The property is located on a small rise just metres from the water’s edge and is the perfect place from which to enjoy the tranquillity of this island paradise. With a range of stunning coastal swims, beautiful natural scenery and a long and rich history which dates back to the Minoan civilisation that occupied the island as far back as 3,650 BC, this trip is a wonderful opportunity to discover this truly fascinating part of the world. WHO IS THIS TRIP FOR? This trip is designed for swimmers who enjoy yoga, or who want to explore the benefits of yoga and how it naturally complements and enhances one's swimming. This trip also offers an idyllic coast for swimming and walking, while being based right on the water’s edge in one of Europe’s most remote villages. Swimmers should have a basic understanding of open water swimming and be capable of completing the short swims distances of an average 3 km daily. -

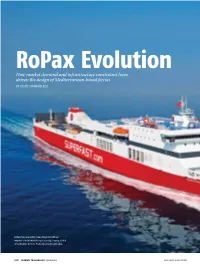

How Market Demand and Infrastructure Constraints Have Driven the Design of Mediterranean-Based Ferries by Costis Stamboulelis

RoPax Evolution How market demand and infrastructure constraints have driven the design of Mediterranean-based ferries BY COSTIS STAMBOULELIS RoPax ferry Superfast 1 was designed with an emphasis on increased cargo capacity, having a total of 2,600 lane meters. Photo by George Giannakis. (22) marine technology January 2014 www.sname.org/sname/mt esigning a RoPax ferry for service in the Mediterranean Sea generally is a very chal- lenging project, having to satisfy a large number of often-contradictory require- ments and to observe constraints imposed by international and national rules of the flag state. Ferries operating in the region must comply with Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS), the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, and European Directive 98/18 in terms of safety and environmental protection. Some national administrations have additional safety rules and other standards concerning a many varied issues ranging from minimum requirements for the comfort of pas- sengers, to requirements for the access and accommodation of handicapped persons, to the transportation of pet animals and hygienic matters in general. The constraints imposed on any particular ferry design are closely connected to the type of service in which a vessel will be employed; the period of the year (summer/winter) during which this service has to be performed; and the characteristics (even peculiarities) of the ports at which a vessel will have to call. In broad terms, RoPax ferries operating in the Mediterranean can be classed in one of the following categories: 1: ferries employed between two or three major ports, either of the same country or of two different countries 2: ferries employed between one major port on the mainland and several smaller (usually island) ports 3: ferries connecting several island ports. -

Italy - Greece VENICE - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS ANCONA - CORFU - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS BARI - CORFU - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS

TIMETABLES 2017 Italy - Greece VENICE - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS ANCONA - CORFU - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS BARI - CORFU - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS Crete • Chania • Heraklion Aegean Islands YEARS www.anek.gr H/S/F OLYMPIC CHAMPION H/S/F HELLENIC SPIRIT F/B KRITI I, F/B KRITI II • Horsepower: 68.500 hp • Horsepower: 68.500 hp • Horsepower: 32.000 hp • Speed: 30 Knots • Speed: 30 Knots • Speed: 22 Knots • Length: 204 m. • Length: 204 m. • Length: 191,8 m. • Width: 25,8 m. • Width: 25,8 m. • Width: 29,4 m. • Passengers: 1.850 • Passengers: 1.850 • Passengers: 1.477 • Garage capacity: 119 trucks &106 cars • Garage capacity: 119 trucks &106 cars • Garage capacity: 105 trucks & 60 cars • Decks: 11 • Decks: 11 • Decks: 8 VENICE YEARS ANCONA eGNaTIa MOTOrWay ITaLy ADRIATIC IGOuMeNITSa - TurKey’S BOrDerS SEA 6 HOurS aND 10' - 670 KM BARI The routes ITaLy - Greece GREECE & PIraeuS - creTe THeSSaLONIKI are jointly operated with SuPerFaST FerrIeS & BLue STar FerrIeS The routes are operated by IGOUMENITSA aIGaION PeLaGOS CORFU AEGEAN SEA The routes are operated by LaNe Sea LINeS IONIAN SEA PIRAEUS PATRAS PELOPONNESE MILOS KALAMATA RHODES GYTHIO CYCLADES CHALKI ANAFI KYTHERA SANTORINI DODECANESE DIAFANI ANTIKYTHERA CRETE KARPATHOS KISSAMOS SITIA CHANIA KASSOS HERAKLION F/B KYDON F/B ELYROS • Horsepower: 35.600 hp • Horsepower: 35.600 hp Βραβείο • Speed: 25 Knots Μετασκευής 2008 • Speed: 24 Knots • Length: 192 m. • Length: 192 m. • Width: 27 m. • Width: 27 m. • Passengers: 1.750 • Passengers: 1.880 • Garage capacity: 111 trucks & 73 cars F/B ELYROS • Garage capacity: 106 trucks & 55 cars The ShipPax Award for • Decks: 10 Ferry Conversion of 2008 • Decks: 10 Welcome on Board ! ANEK LINES offers consistent and reliable services, through well designed sailing schedules, to cover transportation needs. -

Italy - Greece

TIMETABLES 2019 Italy - Greece VENICE - CORFU - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS ANCONA - CORFU - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS BARI - CORFU - IGOUMENITSA - PATRAS Crete • Chania • Heraklion Aegean Islands www.anek.gr ON BOARD SERVICES A LA CARTE RESTAURANT SELF - SERVICE RESTAURANT CAFÉ – BAR ON BOARD SHOPS WiFi INTERNET hot spot WiFi HOT SPOTS SWIMMING POOL TELEMEDICINE SLOT MACHINES The services may not be available on all vessels. For more information please visit www.anek.gr information more For on all vessels. servicesThe not be available may Welcome on Board ! ANEK LINES offers consistent and reliable services, through well designed sailing schedules, to cover transportation needs. At the same time, the comfort of our modern ships and the on- board services and facilities, are designed to cover all professional driver needs, turning your trip into a unique relaxing experience. For Details & Prices: Please contact our Central Cargo Reservation Offices or visit our website at www.anek.gr H/S/F OLYMPIC CHAMPION H/S/F HELLENIC SPIRIT F/B KRITI I, F/B KRITI II • Horsepower: 68.500 hp • Horsepower: 68.500 hp • Horsepower: 32.000 hp • Speed: 30 Knots • Speed: 30 Knots • Speed: 22 Knots • Length: 204 m. • Length: 204 m. • Length: 191,8 m. • Width: 25,8 m. • Width: 25,8 m. • Width: 29,4 m. • Passengers: 1.850 • Passengers: 1.850 • Passengers: 1.477 • Garage capacity: 119 trucks &106 cars • Garage capacity: 119 trucks &106 cars • Garage capacity: 105 trucks & 60 cars • Decks: 11 • Decks: 11 • Decks: 8 VENICE Ancona EGNATIA MOTORWAy IGOumenitsa - TuRKEy’S BORDERS ITALY ADRIATIC SEA 6 hours and 10' - 670 km bari The routes Italy - GREECE GREECE & PiraeuS - Crete are jointly operated with Superfast Ferries & Blue Star Ferries The routes are operated by IGOUmenitsa AIGAION PELAGOS corfU AEGEAN SEA IONIAN SEA PiraeUS Patras peloponnese MILOS RHODES cyclaDES CHALKI ANAFI santorini DODecanese Diafani crete karpathos SITIA CHANIA kassos Offers - Conditions Heraklion • Departures and arrivals are carried out at local time. -

Anek Lines S.A

ANEK LINES S.A. PRESS RELEASE FINANCIAL RESULTS FOR THE FULL YEAR 2010 ANEK LINES despite the adverse economic conditions and the intense competition succeeded in boosting traffic of both passengers and vehicles in FY 2010 Total Traffic for the Group: Passengers 2.7 mil. (+7%), Vehicles 447 thou. (+3%), Trucks 255 thou. (-2%) Group Turnover: € 263.1 mil. ANEK LINES S.A. (ANEK) announces its financial results for the full year from January 1 st to December 31st 2010 (FY 2010), in accordance with the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS): During 2010, ANEK Group operated in the Adriatic Sea (Ancona, Venice), Cretan (Chania, Heraklion), Dodecanese, Cyclades and Northeast Aegean routes through a total of 17 own and chartered vessels. The ongoing financial crisis due to the prolonged recession of the Greek economy, the drop of demand and international trade, the rising fuel prices (in excess of 30%) as well as the intense competition were the main factors shaping the passenger ferry industry during 2010. Despite the prevailing adverse conditions, ANEK maintained market share whereas in some cases like as the Adriatic routes, ANEK managed to boost its share. As far as it concerns the Chania route the entry of a new competitor had caused ANEK to forego market share. As far as it concerns the Cyclades and the Dodecanese ANEK continued to service the public routes. Finally, via its subsidiary “AIGAION PELAGOS” that was incorporated during the first semester of 2010, the Group serviced an East Aegean route via a chartered vessel. Overall, in FY 2010, ANEK serviced 2.7 million passengers versus 2.5 million in 2009, marking a 7% increase, 447 thousand vehicles versus 433 thousand in 2009 marking a 3% increase as well as 255 thousand trucks versus 260 thousand in 2009 marking a 2% decrease due to the drop of merchandise transfer. -

Anek Lines S.A

ANEK LINES S.A. PRESS RELEASE FINANCIAL RESULTS FOR THE FIRST HALF OF 2020 Shrinkage of transport work in Adriatic and coastal shipping Group turnover decreased to €55.4 million versus €72.5 million ANEK LINES S.A. (ANEK) announces its financial results for the period from January 1st to June 30th2020, in ac- cordance with the International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS): The spread of the pandemic COVID-19 during the first months of 2020 brought significant negative impact on the economy. There was a rapid decline in the demand for goods and services while the implementation of emergency measures caused restriction in transfers and, consequently, large losses in maritime transport ser- vices. In the passenger shipping sector, the pandemic during the first half of 2020 caused a significant reduction in all categories of transport work. The strict limitations and bans imposed on passenger transports from and to Italy and the islands, led to a vertical decline in traffic volumes both in Adriatic routes as well as in coastal shipping. ANEK Group during the first half of 2020 operated through owned and chartered vessels in routes of Adriatic Sea (Ancona, Venice), Crete (Chania, Heraklion), Dodecanese and Cyclades, while one vessel continued to be chartered abroad. Having executed 3% fewer itineraries in relation to the first half of 2019, ANEK Group in all routes operated, transferred in total 172 thousand passengers over 370 thousand during the comparable pe- riod (53% drop), 31 thousand vehicles versus 65 thousand (52% drop) and 61 thousand trucks compared to 67 thousand (9% drop). ANEK LINES S.A. -

Greece Travel Guide

Greece Travel Guide Greece is one of the most popular holiday destinations in Europe. Greece, the nation renowned for being 'the birthplace of Western Civilization', has numerous archeological and natural sites that attract travelers from all over the world. Since centuries the country has influenced the world’s thoughts and practices; be it in science (through Archimedes, Pythagoras, and Euclid), philosophy (courtesy Socrates, Aristotle, and Plato), literature (Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey), or even sports (Olympic Games). Located on the Balkan Peninsula, the southern European country of Greece is surrounded on its three sides by seas – Ionian on the west, Aegean in the east, and the Mediterranean on the south. It shares its northern border with Bulgaria, Albania, Republic of Macedonia, and Turkey. Apart from the Greek mainland, there are a number of islands in the three seas under the Greece’s dominion; significant ones include Crete, Cyclades, and the Ionian Islands. Owing to its proximity to the seas, Greece is blessed with pleasant weather for about seven months, between May and November. Most parts of the country experience the quintessential Mediterranean climate, with hot and dry summers, and wet and mild winters. Summer nights are although enjoyably cooler. The people of Greece speak the Greek language. Major holidays include Easter, Christmas, and the Independence Day on 25 th March. Getting In & Around Greece is well connected with almost all countries of Europe by air, water, rail, and road. By Air: The international airports in Athens, Heraklion, Corfu, Crete, Rhodes, and Thessaloniki receive flights from major tourist destinations in Europe.